Jerash Tabernae, thermopolium

Jarash Propylaea Gate; Jarash Ottoman Gov House

Jarash Propylaea Gate; Jarash Ottoman Gov House

Tabernae-Thermoplium was in the shops in the forground behind the cardo

click on image to open in a new tab

Reference: APAAME_20080918_DLK-0148

Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

- from Chat GPT 5.1 Thinking, 19 November 2025

- sources: Baldoni (2018), Baldoni (2019)

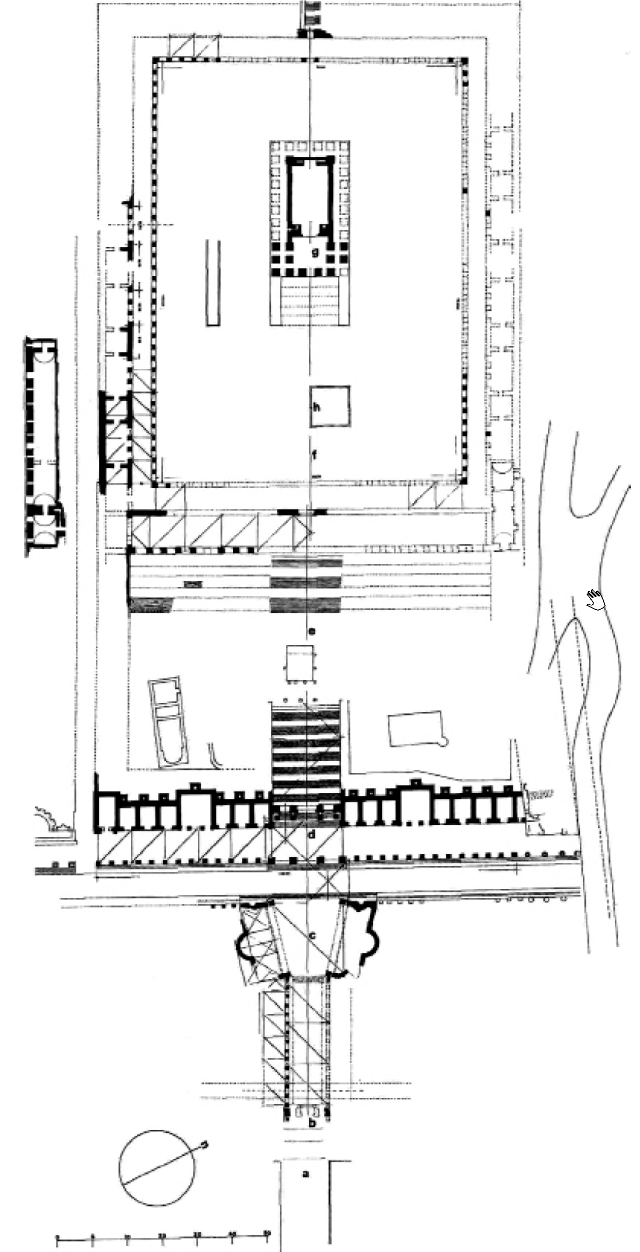

- Fig. 1 Plan of the sancturay of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 1 Plan of the sancturay of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

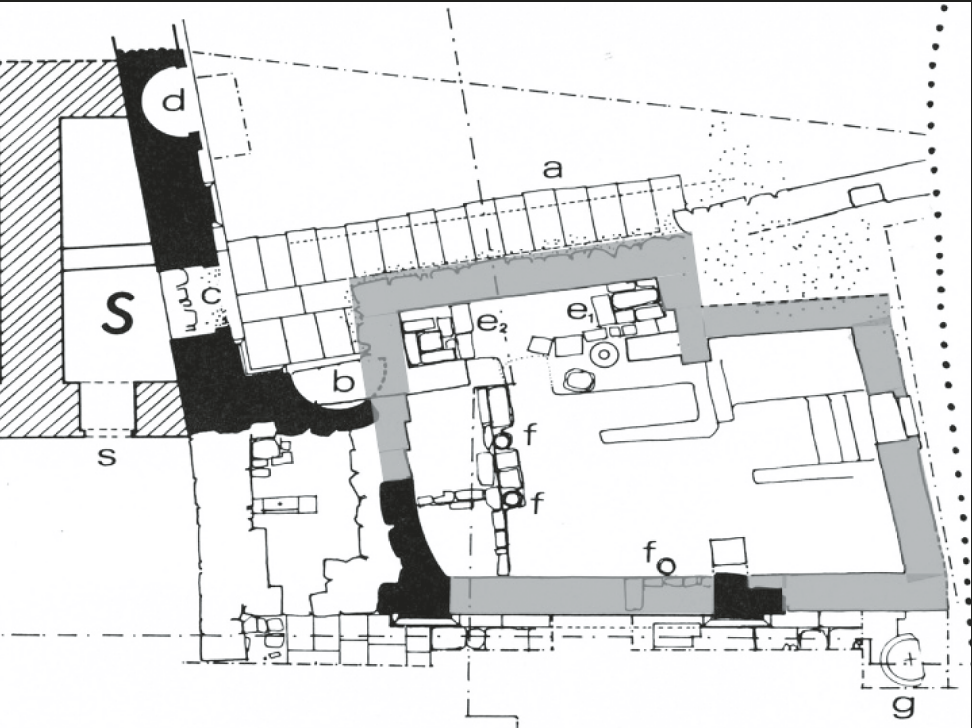

- Fig. 3.17 Plan of the

Byzantine thermopolium from Baldoni (2018)

- Fig. 3.17 Plan of the

Byzantine thermopolium from Baldoni (2018)

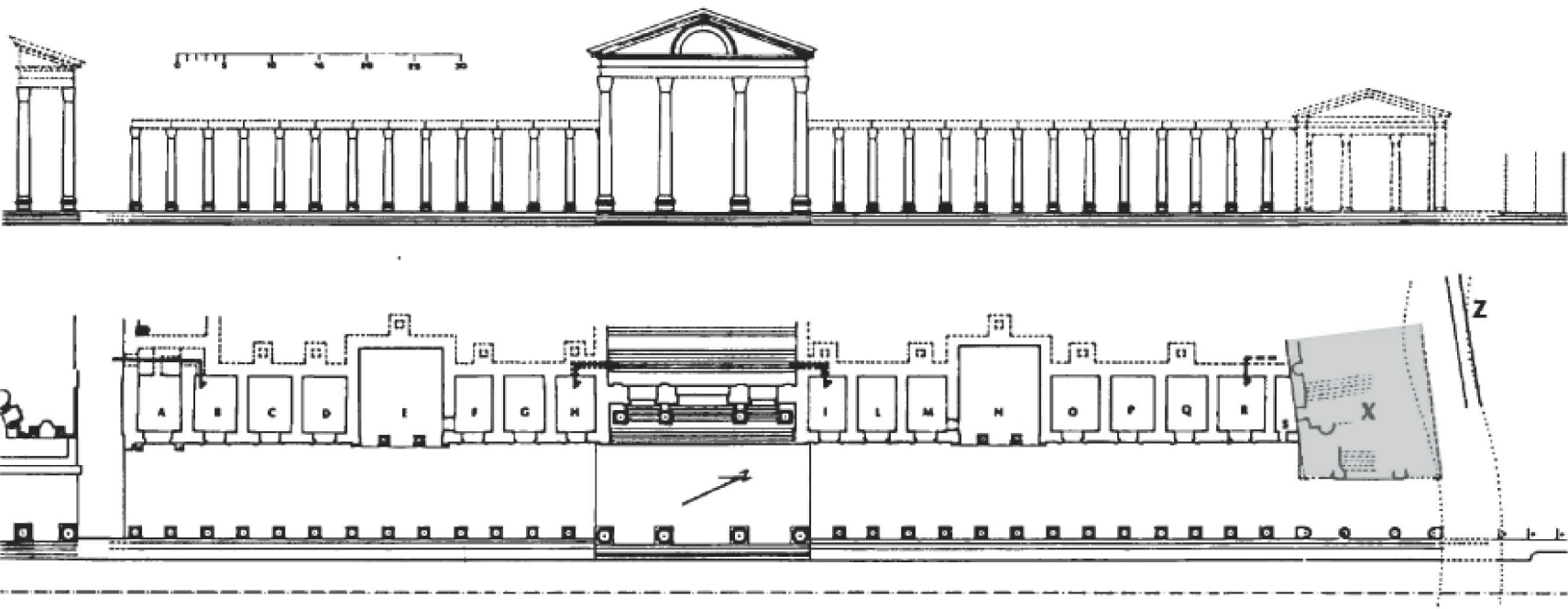

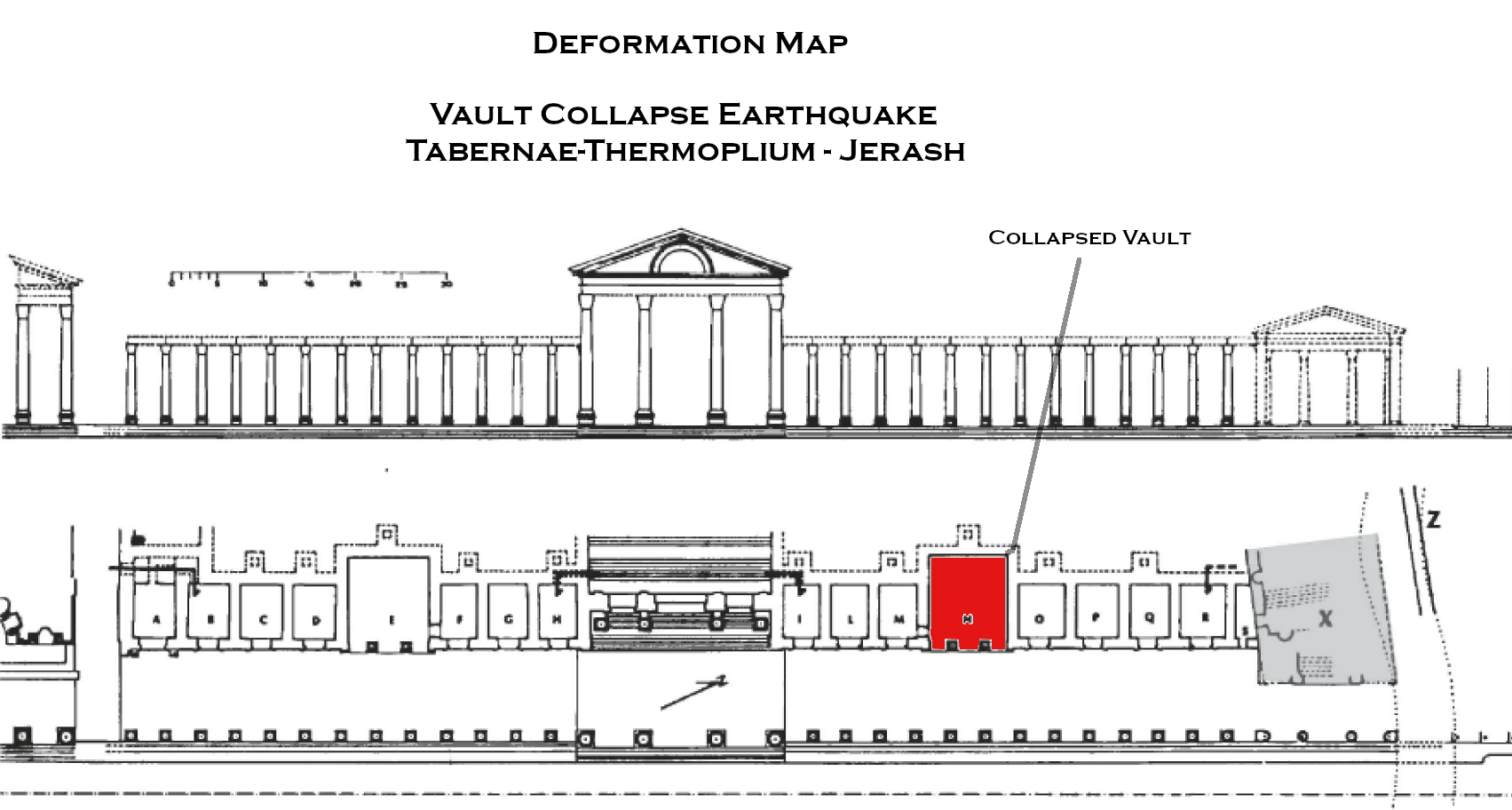

- Fig. 3.3 Front of

shops of the Sanctuary of Artemis on the Main Colonnaded Street from Baldoni (2018)

- Fig. 3.3 Front of

shops of the Sanctuary of Artemis on the Main Colonnaded Street from Baldoni (2018)

- Fig. 3.3 The rooms on

the northern side of the propylaeum from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.4 The rooms on

the southern side of the propylaeum from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.5 The north exedra from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.8 The two rooms

just north of the propylaeum at the beginning of the works of the Italian Mission from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.19 Collapse of

the Roman vaults in the north exedra from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.3 The rooms on

the northern side of the propylaeum from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.4 The rooms on

the southern side of the propylaeum from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.5 The north exedra from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.8 The two rooms

just north of the propylaeum at the beginning of the works of the Italian Mission from Baldoni (2019)

- Fig. 3.19 Collapse of

the Roman vaults in the north exedra from Baldoni (2019)

... The excavations conducted in the shops by the Italians between 1984 and 1987 to restore and consolidate the structures have — where still preserved — brought to light a single level of occupation datable to the transition period between the Byzantine and Umayyad periods. The layer immediately above bedrock was sealed by the collapse of the Roman vaults, probably caused by the earthquake of AD 660 (Fig. 3.9).

This event, rather than the later one in AD 749, seems to be indicated by the material found in this layer, locally produced between the sixth and the first half of the seventh centuries. The context examined includes fragments attributable to ceramic shapes and types that were widespread at Gerasa, characterized by a particular thinness of the walls and by a clay of red colour with small grits of quartz and limestone (Table 3.1).

The absence of findings dated from the mid-fourth to the mid-sixth centuries seems to attest to a long period of abandonment of the building, probably caused by the earthquake in AD 363 and lasting until sometime after AD 551, the date of the new seismic event that devastated Jerash.

To this period belong four folles of Anastasius I or Justin I, minted at Constantinople, bearing on the obverse the profile portrait of the emperor and on the reverse the Greek letter M with a cross above and the mint mark CON beneath (Fig. 3.16).

The reorganization of the area in the Byzantine period led to a radical structural and functional transformation of the building, on the ground floor of which a thermopolium was established (Fig. 3.17).

... The excavation has yielded some other complete cooking-pots and the fragments of about 130 vessels of the same type, scattered over the whole area. On the bottom of one of these remained the residue of food that had been contained within it.

Despite the variety of rim conformation, their shape, arising from the repertoire of the Roman tradition, shows homogeneous features, strictly related to their specific function. The two-handled ribbed, almost globular body has a rounded bottom, particularly well-suited to fit the hearth embers and, together with their thin walls, to make cooking much faster. The thinness of the walls made these vessels too fragile for long-term use, but judging from their massive production and the large number thrown away, we can assume that they were inexpensive. Their technical features seem to indicate that many of them were produced at the hippodrome kilns discovered by Ina Kehrberg and Antony Ostrasz, who were active during the Late Byzantine period15.

The cooking ware retrieved also includes lids with small holes for the steam vent and a large number of frying pans, some with a coarse white-painted decoration on the broad rim, showing that they were used not only for food preparation in the kitchen, but also as serving dishes (Fig. 3.38).

A total of sixty-five bronze coins, heavily oxidized and almost illegible, were collected above the floor level within the building. This number includes four isolated folles, some small groups of three or four pieces found near the benches, and four hoards of seven, eleven, fourteen, and seventeen coins, most of which were small in size. One of the hoards was found inside the waste container on the east side of the room. The manner and place in which it was concealed seem to indicate that it was deposited by one of the occupants of the structure for a reason that, considering its small monetary value, remains unknown.

These coins might represent the savings or disposable income of the occupants of the thermopolium, and therefore their high concentration in this area could be related to the activity of the premises, as well as the presence of numerous Jerash Lamps, found intact and with clear traces of use (Fig. 3.39)16.

It is likely, even if not certain, that the final abandonment of the complex was brought about by the earthquake in AD 660, as the absence of Umayyad occupational activity in the area seems to indicate. However, it is not clear whether this absence could rather be due to the several digs carried out in previous years which, as we observed in the sanctuary’s workshops, had heavily damaged the post-Byzantine archaeological deposits.

In the case of Jerash, the comparitive reading of both the finds and the structure itself, as well as the architectural context in which it was built, allowed a reliable interpretation of the building's archaeology and function. In the absence of detailed indications on both the architecture and the finds from other thermopolia sites of this period, the information obtained from such a reading could contribute to the identification of coeval complexes of the same type. The architectural features and location in the urban framework of the Jerash thermopolium, as well as the nature of the materials retrieved, are indeed in some way typical and can thus provide useful indications to identify the general function and structural arrangement of similar buildings throughout the Byzantine East for which less complete evidence either survives or has been published.

As evidenced by literary sources and by depictions on mosaics and reliefs, tabernae and thermopolia must have existed in most towns of the Roman Empire.17 For some of them, like those of Ostia and the Vesuvian cities, the structural evidence is quite extensive, although information related to the internal arrangements of objects was not recorded.18

Yet little or nothing was known about the taverns of the Byzantine towns, particularly as regards the Eastern Mediterranean regions.

Recent excavations carried out in Sardis, Sagalassos, and Scythopolis, however, provided extensive documentation on some buildings of this type dated between the second half of the sixth and the first half of the seventh centuries AD, whose structural features were examined in the context of the finds evidence.

An important factor, common to all these complexes, is their strategic position in the central area or alongside the main streets of the city. At Sardis five of the ‘Byzantine shops’ recognized as thermopolia were located on both sides of the entrance to the Bath-Gymnasium complex.19 At Sagalassos five interrelated rooms, with a kitchen, a space for consuming meals, and some more private rooms, were situated on one of the main urban squares.20 At Scythopolis six shops, interpreted as units for preparing and selling food, were overlooking the Street of the Monuments, the main pilgrim road which crossed the city.21

All these buildings were identified as taverns based on the presence of specific equipment and fittings, such as masonry benches, hearths, storage vats, ovens, water supplies, and other artefacts indicative of their function. Within one of the excavated taverns at Sardis, a stone mortar placed in a corner of the room was highlighted, along with a masonry platform, similar to the one found in Jerash and, like this one, located on the right side of the entrance.

Large deposits of animal bones, representing refuse from the preparation and consumption of meals, were retrieved from the contexts related to the occupation of the taverns, mostly accumulated close to the areas where the food was prepared.

The recovered materials, which include table and kitchen vessels, glass bottles and goblets, storage vessels, amphorae, and a large number of coins, provided a complete framework of the objects functional to the activity of a thermopolium and allowed a reliable reconstruction of tastes and standards of living of the local population between the sixth and seventh centuries.

15 Kehrberg and Ostrasz 1997. On the pottery produced at the

hippodrome kilns, see Kehrberg 2009.

16 For a typology of the Jerash Lamps, see Kehrberg 2011.

17 On the Roman thermopolia, see Kleberg 1957; 1963; MacMahon

2003; Putzeys and Lavan 2007, with extensive bibliography on

the published buildings. Recently a thermopolium was unearthed

at Monte Iato (Sicily): Isler 2003, 828.

18 On the tabernae and thermopolia of Ostia, Pompeii, and

Herculaneum, see Girri 1956; Jashemski 1967; Packer 1978;

Hermansen 1981, 125–83; Pavolini 1986; Ellis 2004; MacMahon

2005.

19 On the shops of Sardis, see Crawford 1990; Russell 1993; Harris

2004; Rautman 2011.

20 Waelkens and others 2007; Putzeys and others 2008.

21 Agady and others 2002; Khamis 2007; Tsafrir 2009.

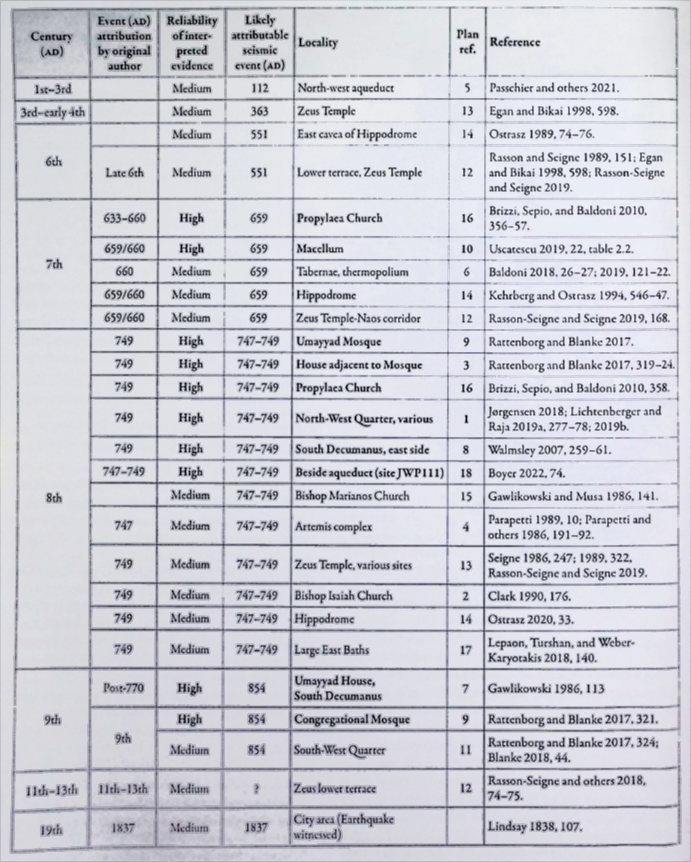

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th | 660 | Medium | 659 | Taberna, thermopolium | 6 | Baldoni 2018, 26–27; 2019, 121–22. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Jerash Tabernae-Thermoplium - a set of vaulted rooms integrated into the sustaining wall of the intermediate terrace of the Sanctuary of Artemis

on the west side of the main collonaded street

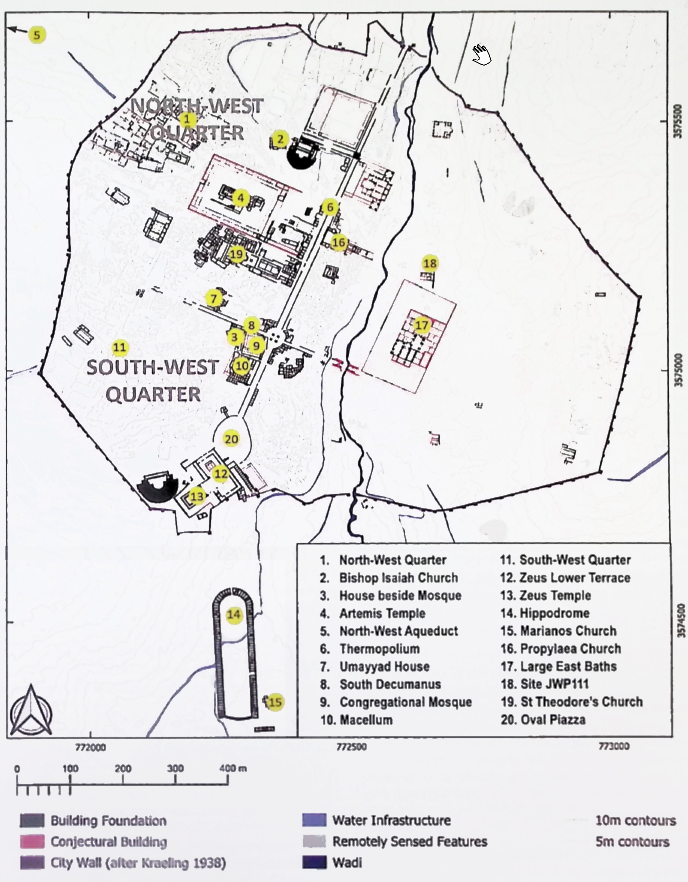

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

Fig. 3.19 |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 3.3 of Baldoni (2018)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jerash Tabernae-Thermoplium - a set of vaulted rooms integrated into the sustaining wall of the intermediate terrace of the Sanctuary of Artemis

on the west side of the main collonaded street

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

Fig. 3.19 |

|

|

Baldoni, D. (2018). A Byzantine thermopolium on the Main Colonnaded Street in Gerasa

. In A. Lichtenberger & R. Raja (Eds.), The Archaeology and History of Jerash: 110 Years of Excavations, Jerash Papers, 1 (pp. 15-37). Turnhout: Brepols.

Baldoni, D. (2019). ‘Archaeological Evidence for Craft Activities in the Area of the Sanctuary of Artemis at Gerasa between the Byzantine and Umayyad Periods’

, in A. Lichtenberger & R. Raja (Eds.), Byzantine and Umayyad Jerash Reconsidered: Transitions, Transformations, Continuities (Jerash Papers 4, pp. 115–158). Turnhout: Brepols.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)