Jerash South Decamanus

Jerash South Decamanus

Jerash South Decamanus

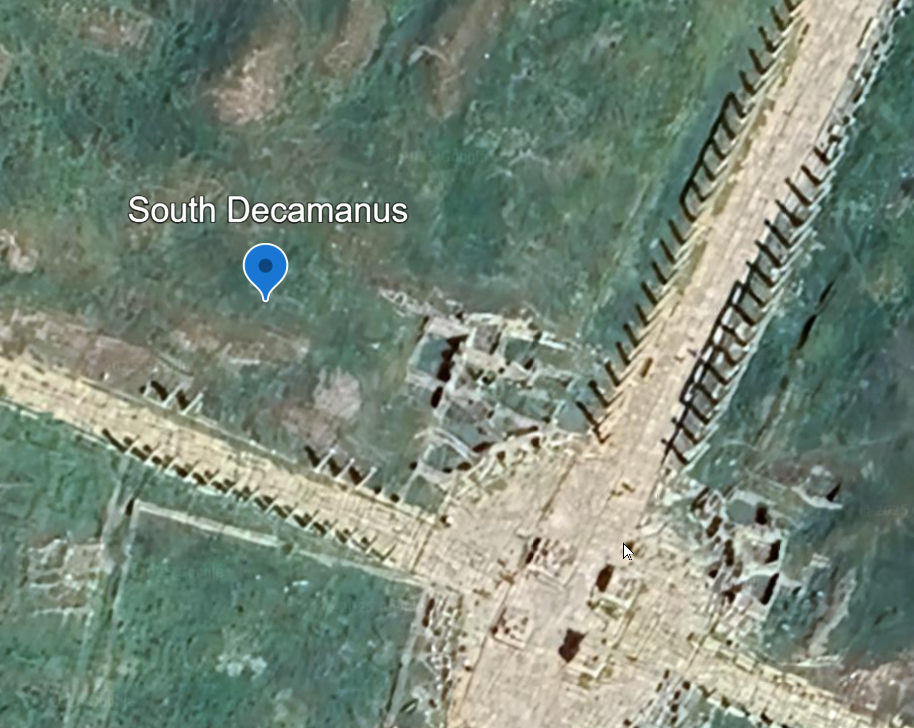

Location as specified by Boyer (2022) although South Decamanus could be the same location as the Umayyad House

click on image to explore this site on a new tab in Google Earth

- from Chat GPT 5.1 Thinking, 18 November 2025

- sources: Gawlikowski (1986); Walmsley (2007)

During the Umayyad period, a substantial residence was constructed behind the shop fronts, arranged around an irregular courtyard shaped by earlier Roman foundations. Architectural details—pavements, retaining walls, benches, and varying room levels—reflect careful adaptation to inherited topography and earlier construction phases.

In the Abbasid period, parts of the area saw functional change, including the installation of pottery kilns and localized levelling. By the end of the 9th century, the excavated portion of the quarter was abandoned, leaving a compact archaeological record that preserves the transition from late Roman urbanism to early Islamic domestic and industrial use.

- Plate Ia Aerial View

of the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Plate Ib Aerial View

the area to the north from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Jerash South Decamanus in Google Earth

- Plate Ia Aerial View

of the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Plate Ib Aerial View

the area to the north from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Jerash South Decamanus in Google Earth

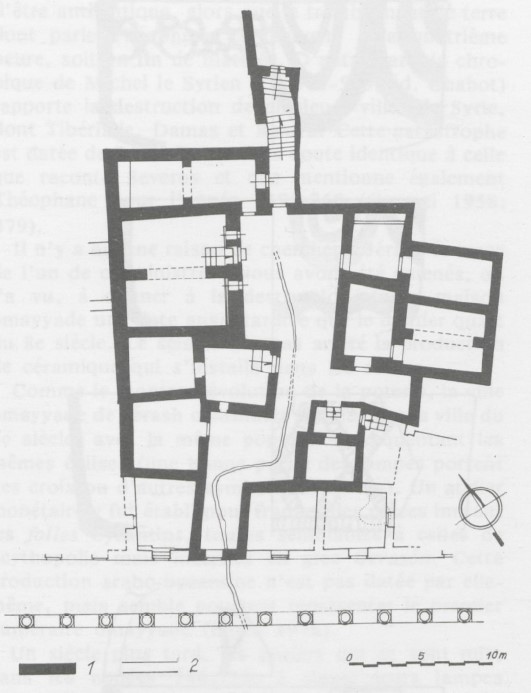

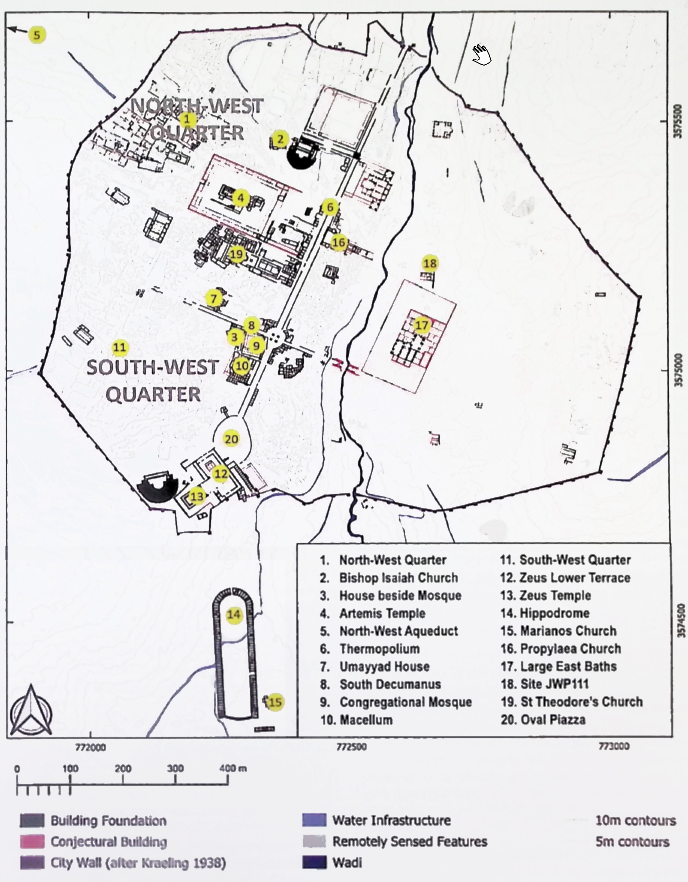

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

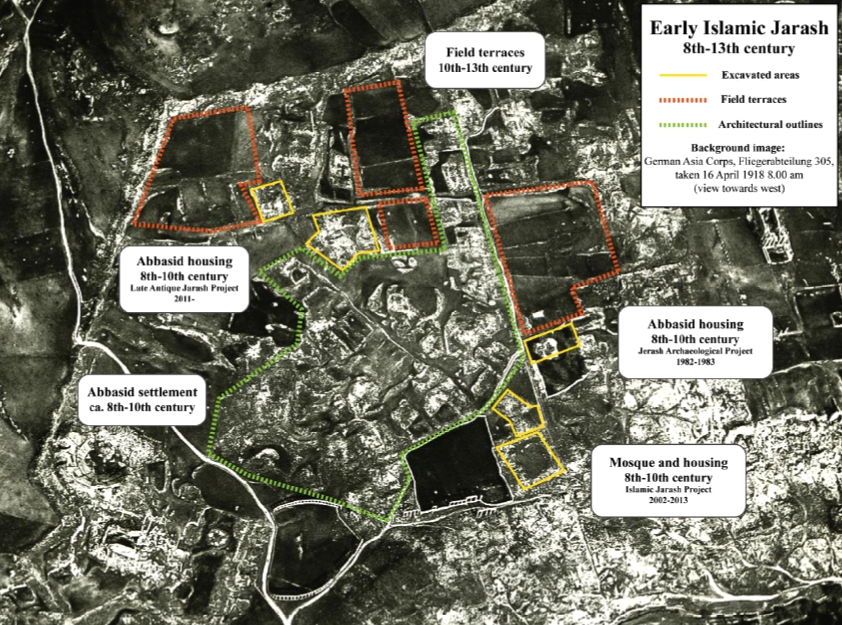

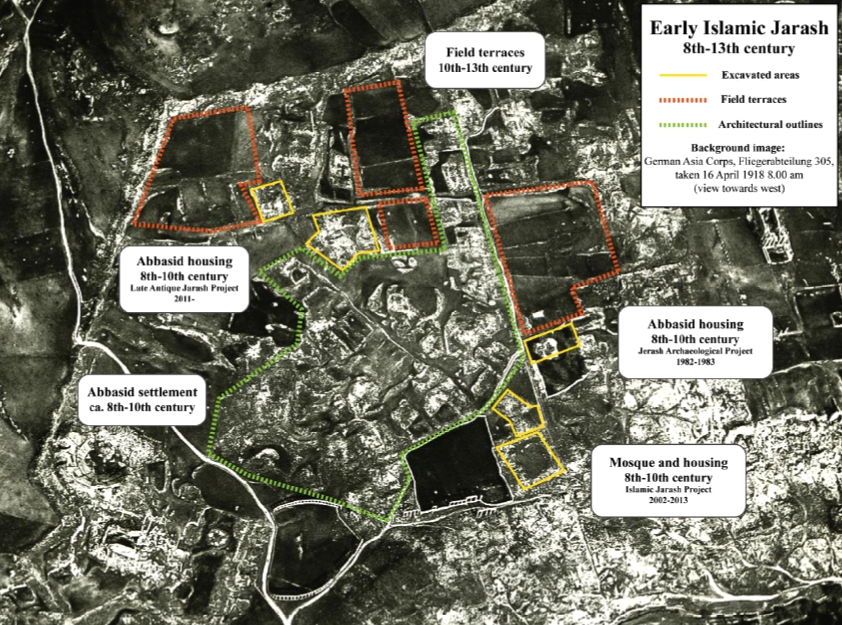

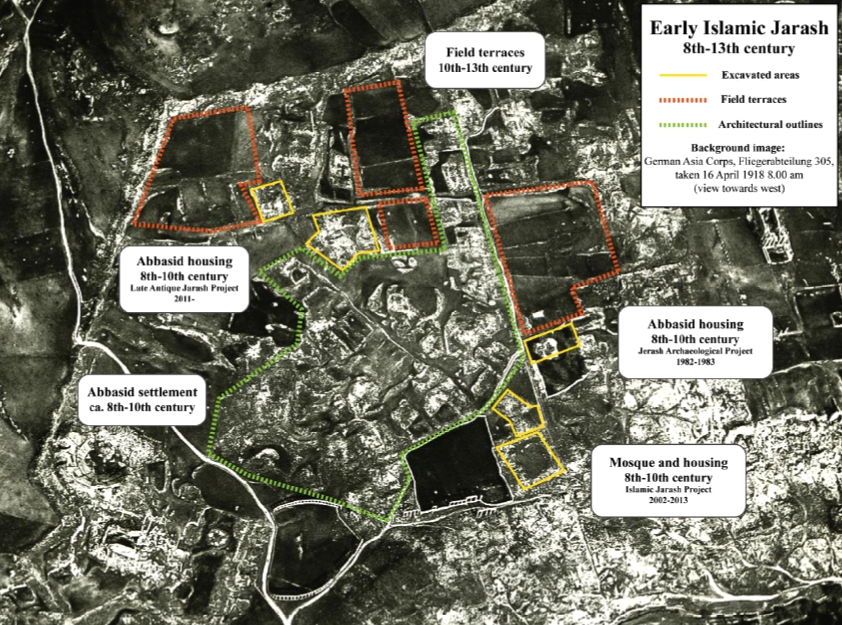

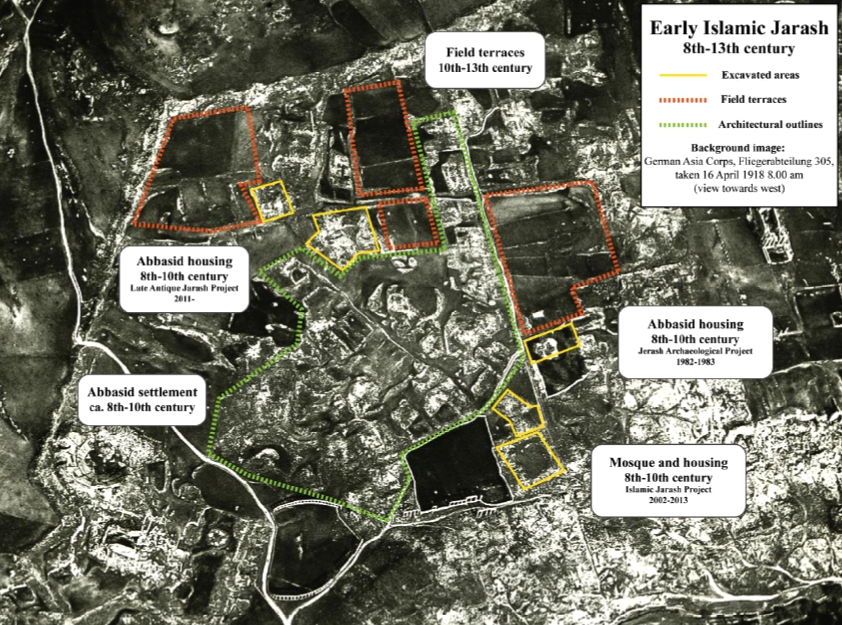

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

- Early Islamic Jerash from

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Early Islamic Jerash

Early Islamic Jerash

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

- Early Islamic Jerash from

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Early Islamic Jerash

Early Islamic Jerash

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

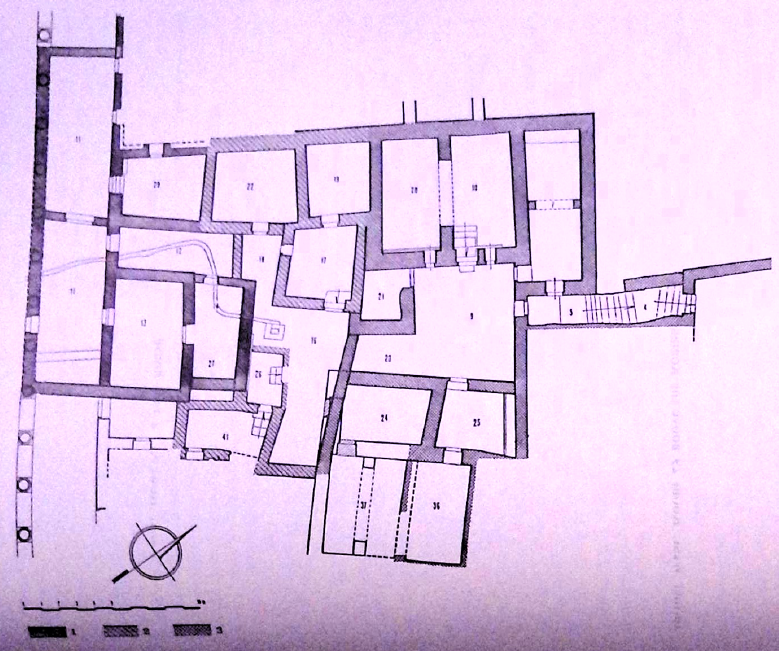

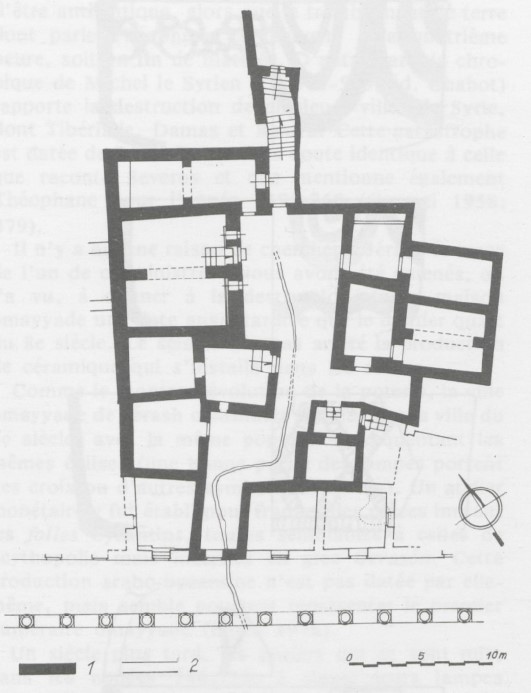

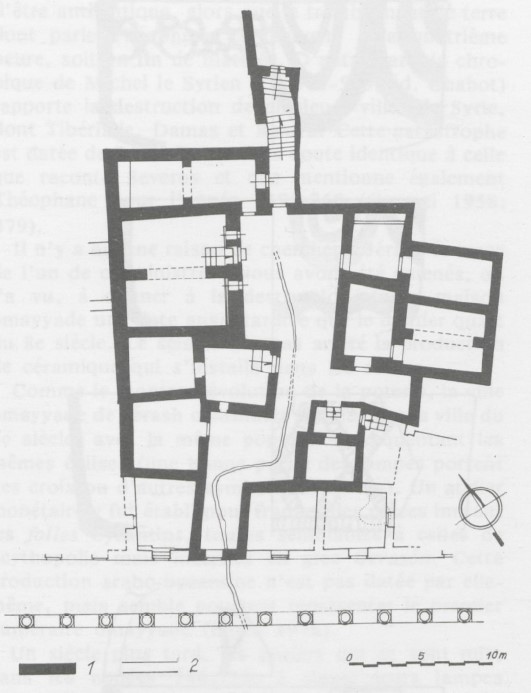

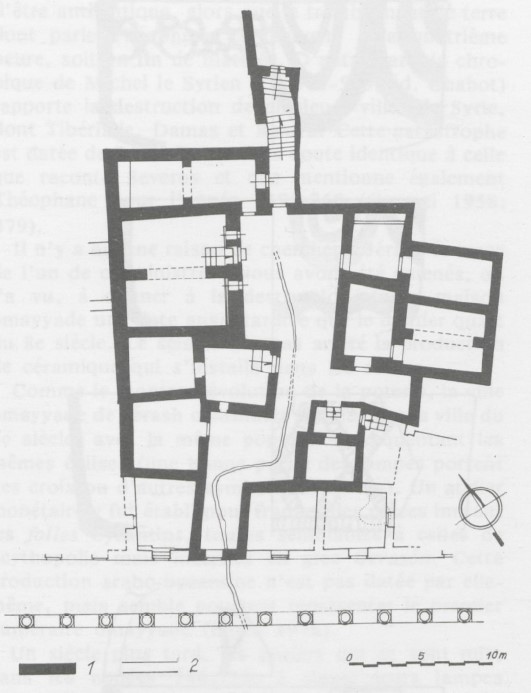

- Fig. 1 - Plan of the

Umayyad House from Gawlikowski (1992)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of the Umayyad House (7th century CE). from A. Ostrasz.

Gawlikowski (1992)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of the

Umayyad House from Gawlikowski (1992)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of the Umayyad House (7th century CE). from A. Ostrasz.

Gawlikowski (1992)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Umayyad House and other structures during the Umayyad Period from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Fig. 3 - Plan of structures

in the Early Abbasid Period from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Umayyad House and other structures during the Umayyad Period from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Fig. 3 - Plan of structures

in the Early Abbasid Period from Gawlikowski (1986)

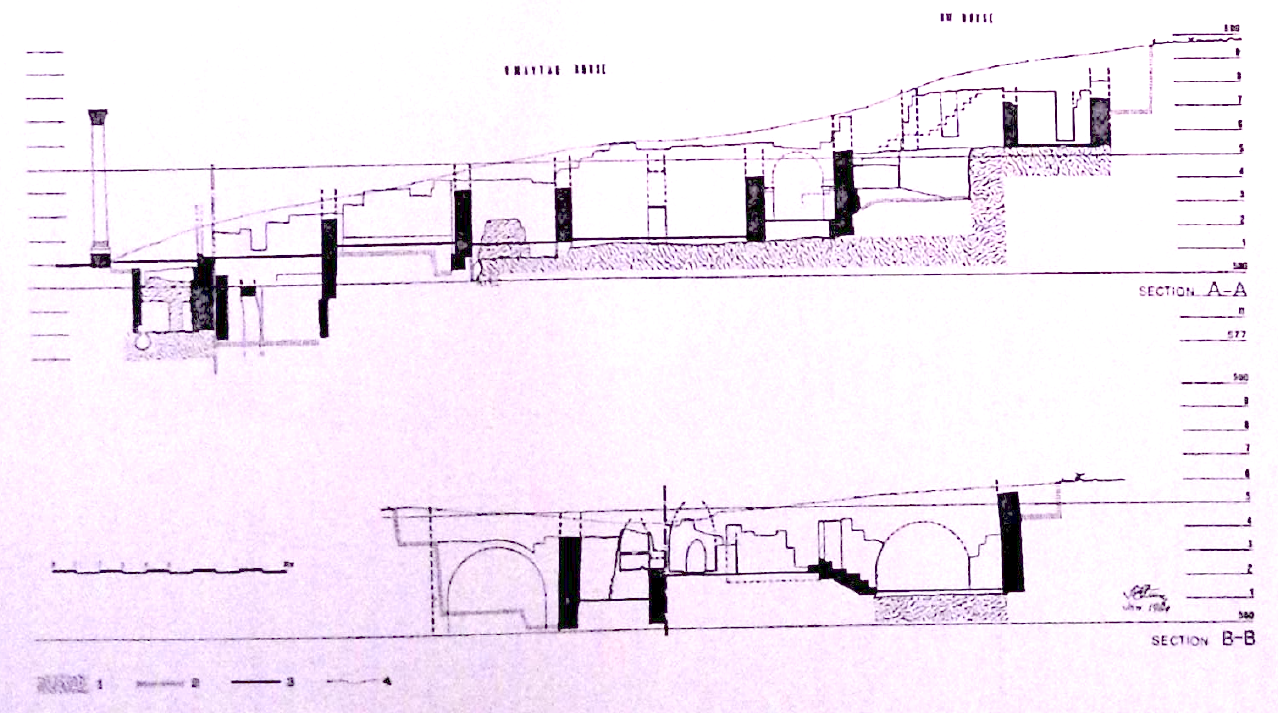

- Fig. 4 Section through

the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Fig. 4 Section through

the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Plate IVa Stone Tumble

under the surface in the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

- Plate IVa Stone Tumble

under the surface in the South Decamanus Area from Gawlikowski (1986)

... At Gerasa the evidence is less categorical but suggests at least sections of the town––but not perhaps all of it––were damaged in A.D. 749. Thick levels of building wreckage were encountered above the cathedral steps, in the church of St Theodore and the group of three churches dedicated to SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John the Baptist, which the Yale Mission attributed to earthquake activity in the 8th c.29 In 2004, further graphic evidence for the impact of the earthquake at Gerasa was recovered from a room on the eastern part of the south decumanus, in which was found the crushed skeletal remains of a human victim and a mule accompanied by a hoard of 148 silver dirhams, of which three were minted in A.H. 130 (A.D. 747/48). Overall, the human and financial loss in the north Jordan valley resulting from the damage inflicted by the earthquake would have been considerable and this is no more apparent, at a micro level, than with House G at Pella.

28 Marco et al. (2003). See also: http://geophysics.tau.ac.il/personal/shmulik/Galei_Kinneret.htm (09 December 2005). An earthquake in the

range 7.0–7.9 is classified as ‘major’, with only one higher classification

(8.0+, ‘great’). A major earthquake would be associated with considerable

or great damage to ordinary (not specially designed) buildings, as clearly

was the case at Pella.

29 Kraeling (1938) 208, 223, 247–49.

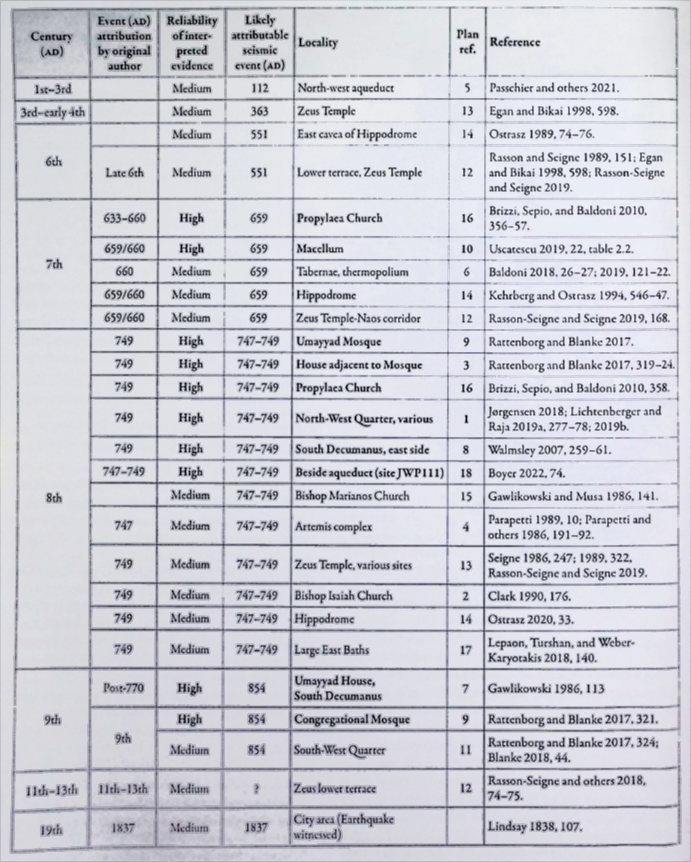

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | South Decumanus, east side | 8 | Walmsley 2007, 259–61. |

| 9th | Post-770 | High | 854 | Umayyad House, South Decumanus | 7 | Gawlikowski 1986, 113. |

The South foundation of Room 32 was used, after the abandonment of the NW house, by the builders of the Umayyad period. Their activity occasioned a new arrangement of the whole area. A staircase was laid upon the stone tumble, leading North to a level 2.4 m above bedrock (Pl. VA). The eastern side of the steps is retained by a wall built to keep in place a large terrace which also leans against the North wall of the house. It was filled with practically sterile soil up to the topmost level of the steps. At bottom level, we have found a coin of Constans II (641–668 A.D.) and contemporary pottery, also in the fabric of the retaining wall.

The steps, separated in two flights by a landing, ended at a door opening onto a platform around the corner of the NE building above the Byzantine fill, delimited by walls parallel to both sides of it. To the West, the upper flight of steps was also bordered by a retaining wall of another terrace above Room 31.

The stairs were found covered with eighth century deposits which also extended to the West (Pl. IVA). Even before these had accumulated, the Umayyad house was already below ground level on the North and West. A foundation trench with the early seventh century fill on the northern side reaches only to the upper courses of the preserved wall, the lower parts of it having been built, after clearing, against the rubble left outside. All the evidence recovered points to the middle of the seventh century as the date of the construction.

While only a few walls were retained on the lower ground level near the Decumanus, the layers immediately below the floors of the house provide consistent evidence. Byzantine sherds and coins, mostly of the sixth century, were found under Rooms 10, 21, 22 and 24, as well as under the courtyard pavement (loc. 16 and 23). A coin of Constans II already mentioned dates the filling of the terrace East of the staircase. Other coins of the same emperor are the latest in the rubble of the NW house. Below the level of Room 7 and above the Roman wall buried about 400 A.D. there were found, in two clusters, eight coins known as Arab-Byzantine, in this case imitations of the folles of Justin II minted in Scythopolis (Bēth Shean) and, in one instance, in Jerash itself (Pl. XV AB). The period of their issue is not exactly known, but it is reasonable to assume that they were gradually replacing Byzantine currency in the first decades of the Islamic government. It is probably not by chance that the original issues of Justin II (565–578 A.D.) are most numerous among the Byzantine coins found; their large circulation induced the Islamic mints to imitate in the first place these, rather than any other types. The latest genuine Byzantine issues are very poor, usually clipped coins of Constans II; we may conclude that the imitation coins are to be dated roughly in the same time, about the middle of the seventh century. Accordingly, the house was built at the beginning of the Umayyad period, about 660 A.D. or slightly later. As its construction is likely to have followed an earthquake, it is tempting to link it with the tremor of June 658 A.D., which caused extensive destruction in Palestine and Syria.

The colonnaded street apparently remained in use since Roman times. The sidewalk does not seem to have been built over in the early Umayyad period, serving its original purpose along the line of shops. However, the shops themselves were entirely restored, including the upper foundation courses in the fill of the cistern (loc. 43), yet without any major change in plan (Pl. V B).

The Umayyad house extends northwards behind four of these shops for 23 m. Although utilizing some earlier foundations as indicated above, it is an entirely new building. It is laid around a courtyard with the main entrance through a passage from the street between shops loc. 29 and 13 (Pl. VI A); another door opened on the opposite end into the staircase. An earlier sewage drain winds its way from the far end of the courtyard and beneath the entrance.

The irregular form of the courtyard (loc. 18, 16, 23, 9) is determined by the position of foundations, inherited from the Roman period, under Rooms 17, 24 and 25. There is a pavement rising gradually northwards, employed for a lengthy span of time at the same level.

The rooms are arranged in two wings, West and East of the courtyard. The western one consists of a row of rooms sharing a straight rear wall with no openings, its outside face being buried in the early seventh century fill, the same that extends in and over the NW house. Some parts of this wall may have been borrowed from older buildings, while the northern wall, though built against the still earlier rubble, is certainly contemporary with the house.

The rooms of the West wing differ in depth as a result of adjustments to the situation the builders found in the area. Thus, the northernmost Room 7 (Pl. VII D) is longer than others, so as to allow an entrance from the courtyard, in line with the door of the staircase. The room is 9.5 m long and only 2.9 m wide. It was below ground level on two sides and lit, as far as we know, by a single window opening above the steps, opposite the terrace to the East and its retaining wall. Allowing for the usual proportions of the window, the ceiling could not be lower than about 3.5 m above the floor, and this is further substantiated by the NW corner of the room, still standing to a height of 4.2 m above the floor level. However, an arch springing from two piers set against the long walls of the room was only about 3 m high and must have carried a partition wall at that level; it was clearly irrelevant as a support for transverse beams, but there are no other hints of a storey above.

The floor of the room, level with the courtyard in front of it, was once covered with a mosaic of which only displaced fragments and a large amount of single cubes have been recovered from the corresponding layer. At far end, there was a stone bench against the wall.

The main room of the house extends to the South of Room 7. It is shorter but much wider (7 m by 7.6 m) and divided in the middle by an arch spanning an opening 4 m wide from East to West (Pl. VIII). Both halves of the room (loc. 10 and 20) were covered separately using this support, with a minimum height of about 3 m above the floor, but actually probably higher. An upper storey is again possible, if its entrance was from the higher ground level outside to the West, but no proof of it has survived.

The flour Is sunk about 0.7 m below the level of the courtyard; four steps inside the worn lead down from the entrance which opens against the arched partition Into loc. 10. To the right and left. there are win¬dows only 0.4 m wide. 1.2 m above the courtyard pavement, each one Illuminating half of the room.

The earthen floor is formed by a compact red soil layer 0.5 m thick, covering bedrock in which a pit in loc. 10 contained a large amount of late Byzantine pottery. The fill below the floor also yielded some typical seventh century forms, such as animal-head lamps, white- painted lugs and black-ware basins. An Abbasid dinar dated to 170/771 A.H. (Pl. XV C) proves that the room was used at the same general level at least as late. Further South. Room 17 intruded into the courtyard space. It was doubled in the Umayyad period by Room 19 behind, in line with the common western wall of the house. The partition between Room 19 and 20 extends along the earlier Room 17, being built against its northern wall. As a result, Rooms 17 and 19 are not on the same axis.

Room 17 was cleared in the Umayyad period down to bedrock, laying bare the earlier foundations. There are, however, traces of a pavement some 0.2 m above the uneven rock. Some Byzantine sherds, but also much earlier finds, e.g. a Ptolemaic coin and another of Agrippa (42/43 A.D.), come from below that level, while on the other hand a pit in the bedrock contained a typical Umayyad storage basin.

There are two steps down from the courtyard and a window, once secured with iron bars, which opens 1.0 m above the floor but level with the exterior pavement to the South. Room 19 has roughly the same floor level, in places at the very base of the walls; beneath, there were some early seventh century deposits within the undulations of the rock. The room had apparently no window, the door to Room 17 being the only opening in its walls preserved up to a height above the floor.

Further South, Room 22 opened from the passage leading to the street and had an earthen floor above Byzantine and Roman layers into which its foundations are set.

The opposite, eastern wing of the house is not symmetrical. In its northern part, it consists of four rooms facing the large Room 16, 20 across the courtyard. The walls are for a considerable part Roman, cut to the South by the retaining wall of the described terrace; coins dated about early A.D. were found beneath this wall and the pavement of the rooms.

Room 25 was entered from the West and Room 24 from the South through an admitted Roman doorway. The former has a stone bench and a retaining border along its northern wall used probably for storing household utensils. From each room there was access to another room behind (loc. 36 and 37), the latter with a completely preserved arch in the middle.

The larger part of the courtyard (loc. 16) opposite Room 17 extended further East, ending in line with the rooms of the eastern wing. A small sunken space (loc. 26), reached by several steps (Pl. VI B), led to a cellar (loc. 27) and an open recess at the same level, above the filled cistern loc. 41, from which other steps led down to an artificial cave dug out in the rock beneath the shop loc. 42. This storage complex was delimited from the courtyard (loc. 16) by a stone fence.

The walls of the house, with the exception of fragments inherited from earlier times, are built of reused stones varying in size but roughly arranged in courses, with stone chips and mud between them. There is usually no core fill between the faces and no bonding stones. The walls were probably mud-plastered, the roofs certainly made of wooden beams. The presence of a second storey, while not excluded, could not be ascertained.

It seems that grouping of rooms in pairs was a constant habit in relation to the pattern of family life in the Umayyad period. There are three sets of two-room suites (loc. 17-19, 25-36 and 24-37), with the room behind apparently windowless. These could have served as living quarters for subdivisions of the family, the front room being in each case devoted to daily activities and the other, darker one, for sleeping. Room 10/20 and 7 apparently served the whole household for common meals, receptions and the like.

It is remarkable that no kitchen could be identified in this otherwise preserved house (all the ovens found belong to a later phase), these installations must have been quite rudimentary. The only sanitary facility is the covered sewer channel in the courtyard.

One of the results of this excavation which merits attention is the established fact that the life of Jerash as a city did not end in the end of the Umayyad period. There is no evidence for the earthquake of 746/747 A.D. that destroyed Pella and which supposedly marked the end of Jerash as well. On the contrary, the Umayyad House remained in use for quite a while after this date.

A convenient criterion of chronology is the appearance of red-painted pottery, known at Pella from the last years of occupation there, but obviously predominant for a lengthy span of time as far as the house in Jerash is concerned. Besides, there is the clear evidence of lamps dated in the second half of the eighth century, quite common among our finds.

One of the mid-eighth century lamps was actually found in the wall of the small room (loc. 21) built in a corner between Rooms 17 and 10/20. While the walls of this room lay directly on a Byzantine level forming the floor, this is about 0.5 m lower than the pavement in the adjacent courtyard and is covered without transition with an eighth century fill. It thus seems clear that the pavement was removed in this place when Room 21 was built.

Soon after, more important changes took place. The Umayyad House was divided into three separate dwellings. This was done by means of erecting a few partition walls and blocking several doors (Fig. 3).

The South wall of Room 24 was rebuilt at this time above the threshold and extended West to join the corner of Room 21 (Pl. III A). The living unit thus created included the main rooms of the Umayyad House (loc. 10/20 and 7). The courtyard (loc. 9, 23) was accessible only through the stairs from the North (Pl. VII A). The floor level remained unchanged, except for Room 24 which went out of use, at least at the preserved level. Its two extant doors were blocked above some early deposits on the original pavement, while later layers were disturbed by the kilns of the terminal phase. Rooms 25, 16 and 37 yielded, on the contrary, late eighth century potsherds at the floor level. The access to room 37 at this stage is not yet clear, pending additional work still needed in this part of the house.

The part of the Umayyad House around the courtyard (loc. 16) became a separate dwelling which included Rooms 17, 19 and 22. The passage to the street was closed above the sewage drain and the courtyard could then be approached from the East, through a doorway in the wall crossing the filled cistern loc. 41.

The blocking of the original way of access to the house resulted in the creation of a recess (loc. 18) leading to Room 22; it was approached through the former window of Room 17, now level with the floors on both sides, for that of Room 17 rose for about 0.3 m, preserving traces of a hearth and many smoked cooking pots.

The SW corner of the courtyard (loc. 16) received a rectangular raised border above a well linked with the sewage drain; this was used for refuse disposal and precluded any direct communication with loc. 18 behind. The drain remained viable down to the Decumanus, but was blocked uphill from the well.

The former shops along the street were in the meantime developed into yet another house. A wall was built through the space formerly occupied by one of them (loc. 28/42), thus making the neighbouring Room 13 considerably larger. Behind, another room was added above the former cellar (loc. 27) and a part of the passage above the sewer (loc. 14); the resulting room had its living floor level with the top of the preserved partition between the two, the cellar having been filled with soil containing eighth century lamps and sherds. The same fill occurs in Room 13 above the Umayyad level. There is a corresponding threshold between this and the back room (loc. 14/27), which had also another entrance from the former passage between the courtyard and the street, now closed at the far end (loc. 12).

This three-room unit opened into a part of the colonnade, by then enclosed to serve as a courtyard. Only the side walls of the enclosure remain, any blocking between the columns that might have been preserved having been removed during the restoration work in the early seventies. However, there remains a threshold cut in the stylobate in front of the entrance to Room 13.

There is also another threshold in the West cross-wall of this courtyard, suggesting that what lies behind belonged to the same house. Another stretch of the enclosed colonnade opens there into Room 29 and two other unexcavated rooms further West. Room 29 above the Roman cistern had two late levels, the higher one being associated with a pavement in front of it and a door leading West to the next room.

The sherds in the fill of all three late houses include, beside red-painted pottery, the so-called cut-ware bowls and lamps decorated with a vinescroll, typical of the later half of the eighth century. While the Abbassid coins are very rare, one of them proves, as we have seen, that Room 10/20 was used roughly at its original level as late as 770 A.D.

The latest use of the area is connected with the installation of pottery kilns (Pl. IX), after the housing had been at least partially abandoned, apparently as a result of another earthquake indicated by the massive stone tumble in several rooms. Most doors were blocked at this occasion, and the rooms later used, if at all, at a much higher level, as shown by the careless, often overhanging upper courses of several walls. However, a new house was built at the North end of the excavated sector. We have cleared only one room (loc. 1), right under the modern surface. Its floor is about 1 m above the top level of the staircase of the Umayyad House, by that time covered with eighth century deposits.

Three of the kilns were installed in the northern part of the Umayyad House. The biggest, kiln 1, stood practically on pavement level of the courtyard, while smaller kilns 2 and 3 were built over the fill of Room 24, their openings cut through its western wall. All three kilns were surrounded by fill and opened into a small area (loc. 23), a part of the former courtyard by now enclosed and provided with a door from the remaining part of it (loc. 9). The staircase door was blocked and the only access to the kilns must have been through the then filled Room 10/20, divided by a wall on the line of the collapsed arch.

Kilns 1 and 3 were built mostly of stones with some red bricks in between, while kiln 2 was exclusively in brick. They had well preserved fire chambers with the intermediate floors supported by piers of round bricks and, in the big kiln 1, by a reused basalt mortar set in the middle. The domed upper chambers were preserved to a considerable height and the arched openings complete.

The fill inside the kilns and at corresponding higher levels outside contained several complete cooking pots apparently produced there, and also Abbassid lamps, cut-ware bowls and red-painted bowls. The working level was further marked by the presence of some typical buff-ware barbotine fragments and green-glazed sherds which cannot date earlier than the ninth century.

It appears from finds of the same type that the courtyard (loc. 16) and the adjoining Room 17 were still in use at that time, but the house along the colonnade was already buried up. In the front enclosure, another kiln was found, opening to the North into Room 13/27. This kiln was again well preserved, with piers of brick around the fire-chamber and a mortar in the middle, an arched entrance in brick and brick walls strengthened with stones and soil from outside. The fill has shown that the red-painted bowls were the specific product of kiln 4, certainly contemporary with the other three.

No sign of occupation later than the ninth century could be identified in the excavated area.

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | South Decumanus, east side | 8 | Walmsley 2007, 259–61. |

| 9th | Post-770 | High | 854 | Umayyad House, South Decumanus | 7 | Gawlikowski 1986, 113. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

a room on the eastern part of the south decumanus |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

South Decamanus |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a room on the eastern part of the south decumanus |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

South Decamanus |

|

|

Gawlikowski, M. (1986). A Residential Area by the South Decumanus.

In F. Zayadine (Ed.), Jerash Archaeological Project, I: 1981-1983

(pp. 107-136). Amman: Department of Antiquities.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

Walmsley, A. G. (2007a). Early Islamic Syria: An Archaeological Assessment. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Walmsley, A. G. (2007b). Households at Pella, Jordan: domestic destruction deposits of the mid-8th c

. In L. Lavan, E. Swift & T. Putzeys (Eds.), Objects in Context, Objects in Use: Material Spatiality in Late Antiquity, Late Antique Archaeology, 5 (pp. 239-272). Leiden: Brill.

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)