Petra - Jabal Khubthah

APAAME

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

- Reference: APAAME_20181017_MND-0190

- Photographer: Matthew Neale Dalton

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Jabal Khubthah | Arabic | جابال كهوبتهاه |

| Jabal Umm al Amr | Arabic | جابال ومم ال امر |

| the "high place(s)" |

Introduction

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 14 January 2026

- source: Tholbecq et al. (2014)

Recent archaeological work has refined this view, showing that Jabal Khubthah functioned as a complex, multi-purpose area rather than an exclusively cultic precinct. Excavations have documented a variety of architectural forms and uses, indicating that the area combined religious, domestic, and possibly administrative activities within a suburban zone closely connected to the life of the city ( Tholbecq et al. 2014).

Petra - Introduction Webpage

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

Maps, Aerial Views, and Plans

Maps

- Fig. 1 - Location Map from

Tholbecq et al (2014)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Localization of the Jabal Khubthah within Petra (S. Delacros).

Tholbecq et al (2014)

Aerial Views

- Jabal Khubthah in Google Earth

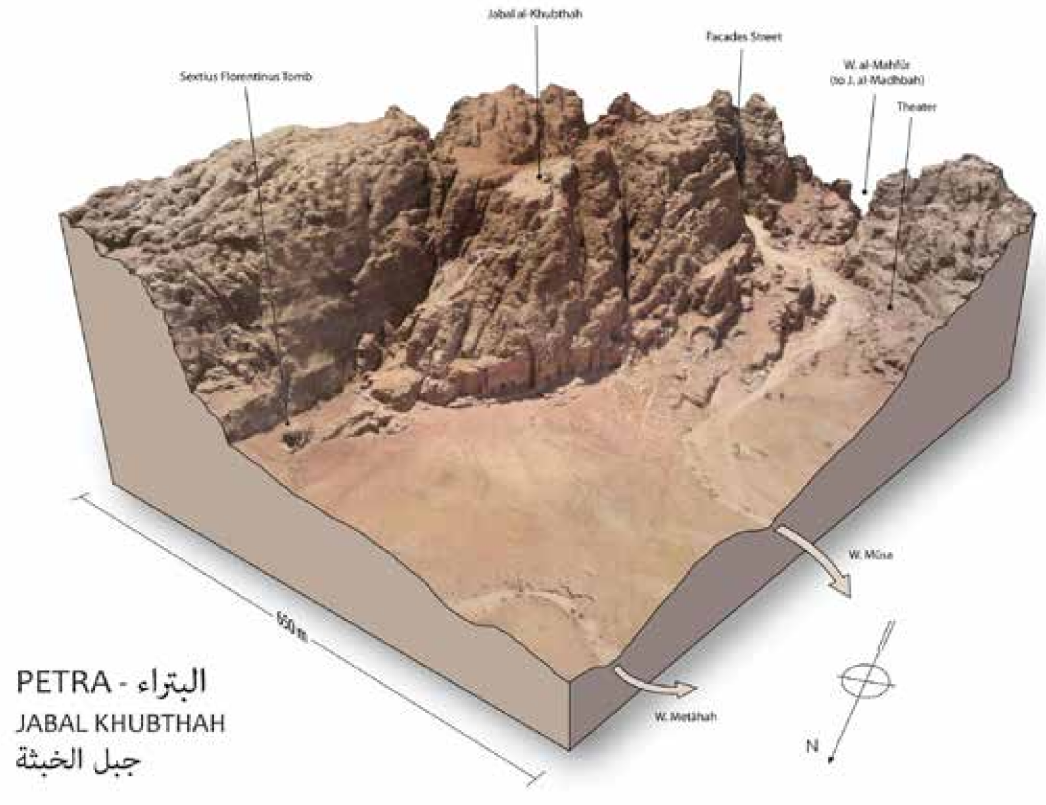

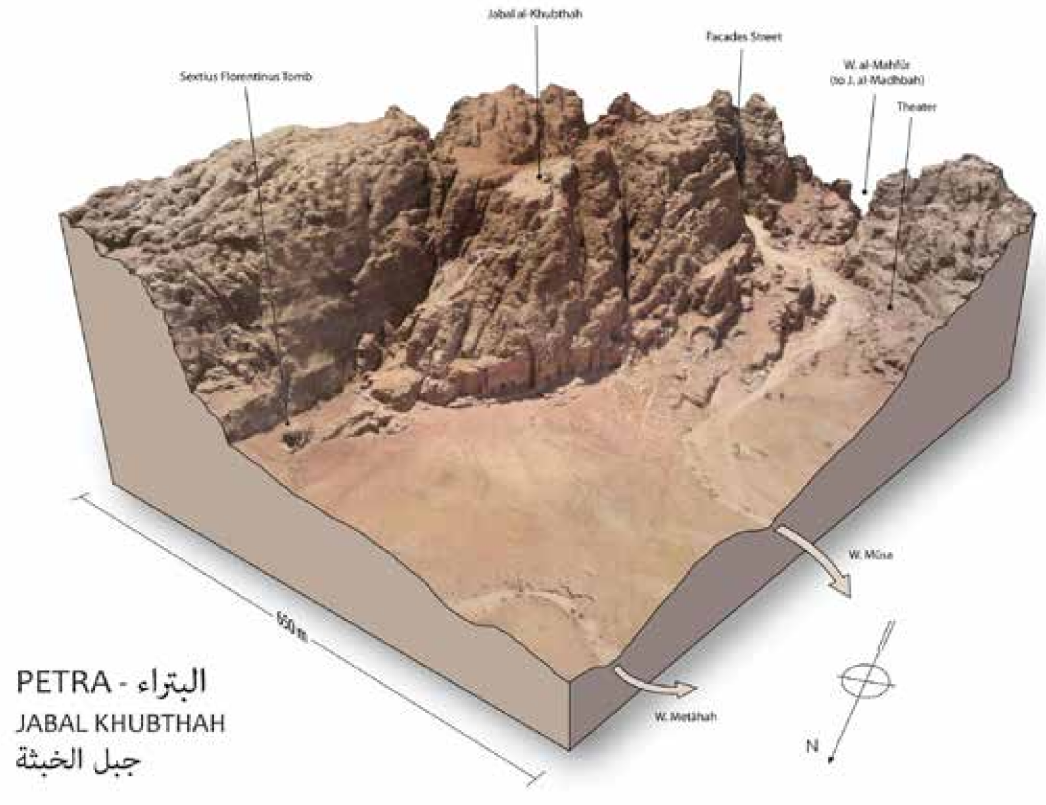

- Fig. 16 - 3D View of the

Jabal Khubthah massif from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

3D Model of the Jabal Khubthah massif, seen from the northwest

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018)

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Plans

Site Plans

Normal Size

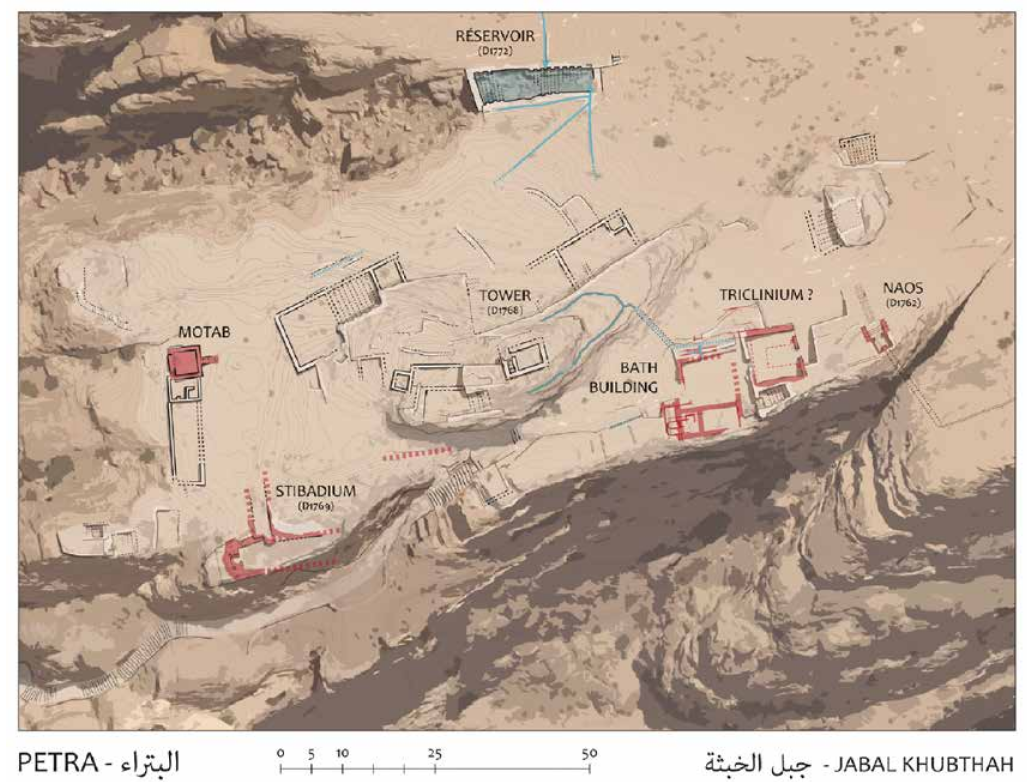

- Plan of Jabal Khubthah

from Tholbecq et al (2019)

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

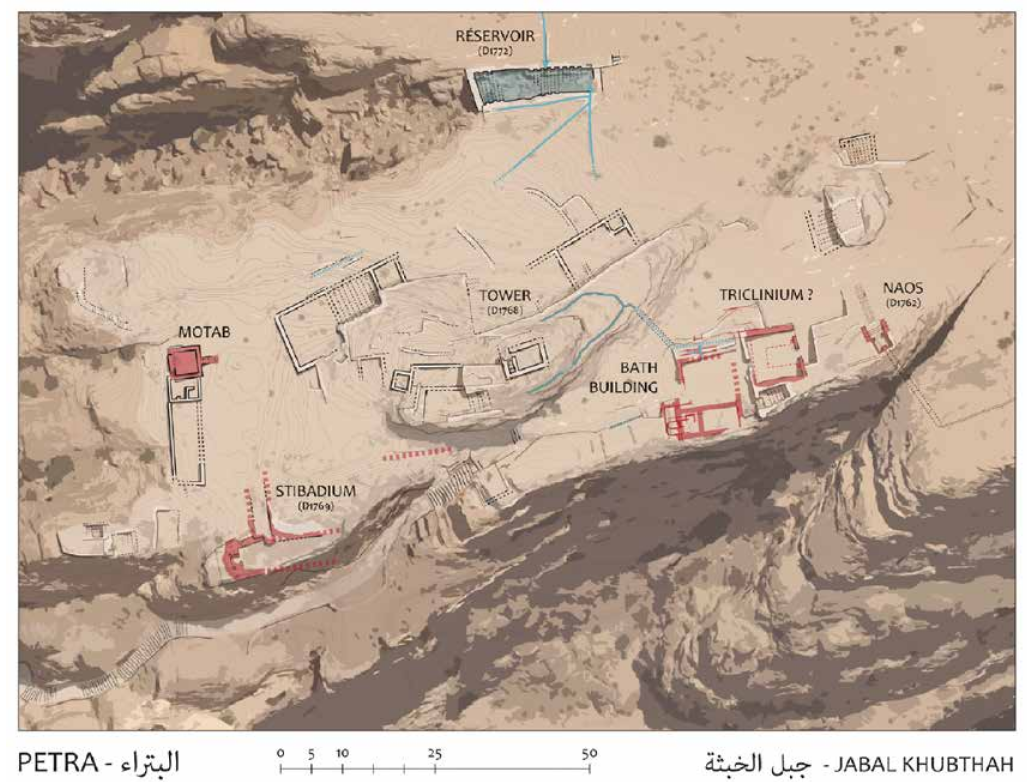

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 17 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah summit plateau from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Plan of the Jabal Khubthah summit plateau

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

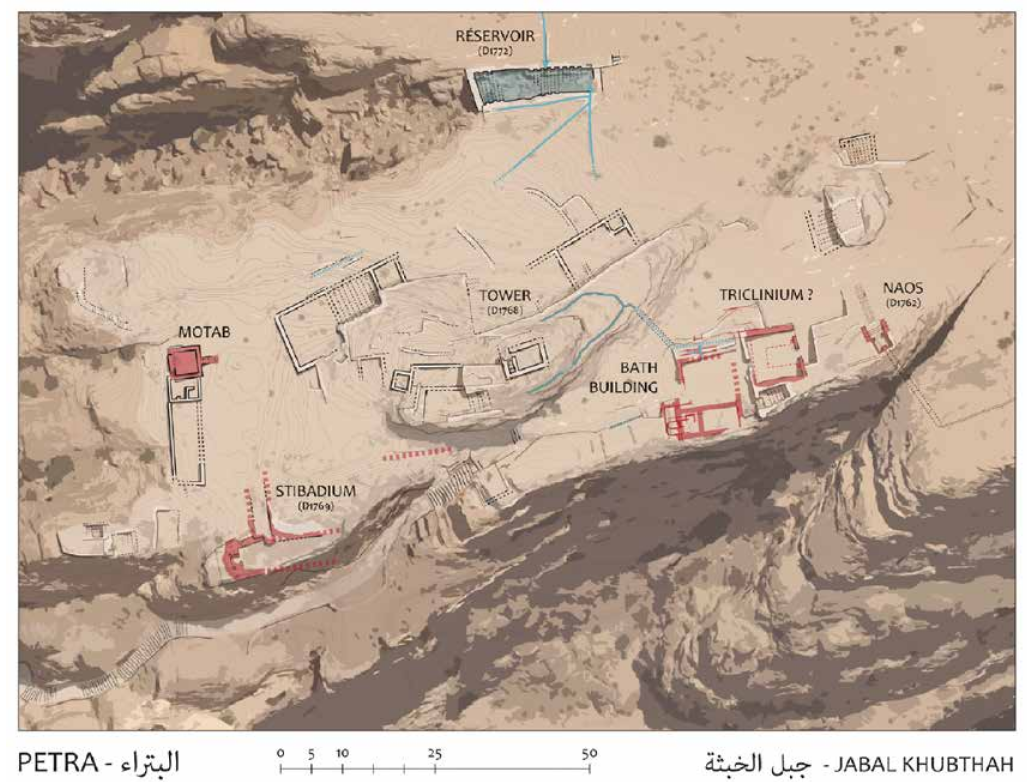

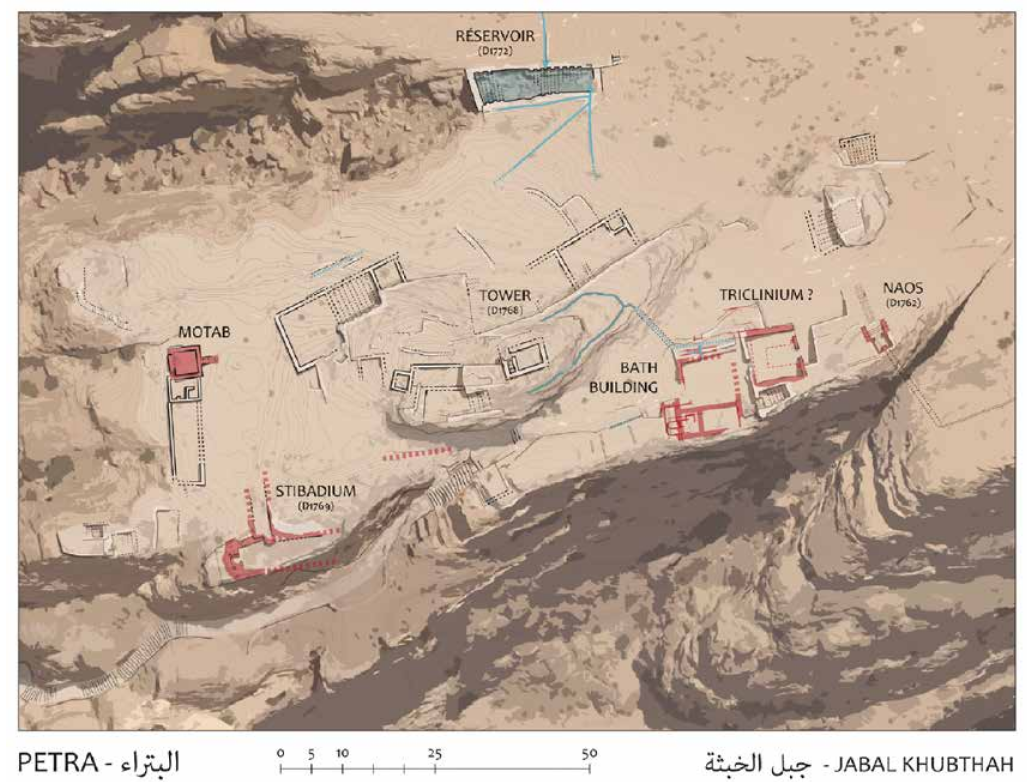

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 25 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah highlighting structures that may belong to a first occupation of the sector from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

Plan Jabal Khubthah summit plateau highlighting structures that may belong to a first occupation of the sector

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Magnified

- Plan of Jabal Khubthah

from Tholbecq et al (2019)

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 17 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah summit plateau from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Plan of the Jabal Khubthah summit plateau

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 25 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah highlighting structures that may belong to a first occupation of the sector from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

Plan Jabal Khubthah summit plateau highlighting structures that may belong to a first occupation of the sector

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Area Plans

Sector 6000

Normal Size

- Fig. 3 - Orthophoto of

Sector 6000 from Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000

By N. Paridaens

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Magnified

- Fig. 3 - Orthophoto of

Sector 6000 from Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000

By N. Paridaens

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Bath Complex

Normal Size

- Fig. 2 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah bath complex from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Jabal Khubthah bath complex at the end of the 2017 campaign

(MAFP/Ifpo - Th. Fournet 2018, on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 18 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah bath complex showing restoration work locations from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Plan of Jabal Khubthah bath complex at the end of the 2017 season showing restoration work locations

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Magnified

- Fig. 2 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah bath complex from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Jabal Khubthah bath complex at the end of the 2017 campaign

(MAFP/Ifpo - Th. Fournet 2018, on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 18 - Plan of

Jabal Khubthah bath complex showing restoration work locations from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Plan of Jabal Khubthah bath complex at the end of the 2017 season showing restoration work locations

(Th. Fournet, MAFP/Ifpo 2018 on a topographic base map of S. Delcros/N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Phasing

East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6)

- from Fiema in Tholbecq et al (2019)

- 3 main phases of construction and occupation

- two main occupation periods (Nabatean and Late Roman/Early Byzantine - 3rd-5th century CE)

two destruction episodes, probably both seismic; the first ending Phase 2 and the second ending the occupation in Phase 3

| Phase | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nabatean |

|

| 2 | Late Roman/ Early Byzantine |

|

| 3 | Byzantine |

|

End of Phase 2 Earthquake - 4th century CE

Discussion

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Dating. The dating of this phase is difficult. The post quem date for the beginning of this phase is the end of the 1st c. A.D. The relevant soil deposits located outside and against walls 6000/6001 are loci 6008 and 6016 (see Fig. 5). The former appears like a dump with a lot of mixed residual sherds, both Nabataean and Roman of the 2nd-3rd century date. On the other hand, locus 6017, i.e., one directly below locus 6008, contained only cooking pots and tableware dated to the 1st c. A.D. Pottery from the sounding inside the structure, i.e., the corner between walls 6000 and 6021 was only slightly more informative. Upon the removal of the pavement 6011, the soil loci excavated were from the top: 6020, 6022 and 6023 (see Fig. 6). All contained a mix of Nabataean, Late Roman and Byzantine sherds of the 2nd-3rd centuries, the latter date perhaps closer indicating the beginning of Phase 2. As for the end of this phase, its dating also depends on when the pavement was laid out – Phase 2 or 3 (vide infra pilasters 6014 and 6014); it could have happened sometime in the 4th century, presumably as the result of the 363 earthquake. All in all, Phase 2 may perhaps be dated to the 3rd–4th centuries A.D.

End of Phase 3 Earthquake - 5th or early 6th centuries CE

Discussion

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Dating. Notable is the presence of the 5th century pottery (loci 6003 and 6005, 6009, 6010). All loci mentioned here also contained 4th century sherds and locus 6010 yielded fragments of ceramic lamps decorated with crosses. As mentioned above, installation 6007 stands on soil locus 6008 which contained 4th century sherds with a lot of residuals (Nabataean-Roman of the 2nd-3rd century date) and also one Robinson M334 amphora (see Fig. 5). It is therefore reasonable to suggest that of the earthquake of A.D. 363 ended the duration of Phase 2, and Phase 3 began soon after that seismic event, with the reconstruction of the structure. It seems that not long afterwards, another earthquake was responsible for the final destruction and the subsequent abandonment of the structure excavated in Sector 6000. It is tempting to propose the enigmatic A.D. 419 tremor recognized on at least one site in the Petra Valley as responsible for that final destruction. However, other seismic events of the 5th or even early 6th century, which are not historically documented, might have also been responsible.

End of Phase 2 Earthquake - 4th century CE

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls inferred from rebuilding evidence | East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6)

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Description

|

End of Phase 3 Earthquake - 5th or early 6th centuries CE

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed arches and Stone Tumble suggesting Wall Collapse | East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6) - locus 6004

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Figure 15

Figure 15The main stone tumble, locus 6004. View from SE. By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

|

| Collapsed arches | East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6) - locus 6004

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Figure 11

Figure 11Remains of both arches as collapsed on pavement 6011. Walls 6000/6001 and superstructure 6027 on the left side. View from the NW. By Z.T. Fiema Tholbecq et al (2019) |

|

End of Phase 2 Earthquake - 4th century CE

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls inferred from rebuilding evidence | East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6)

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Description

|

VIII + |

End of Phase 3 Earthquake - 5th or early 6th centuries CE

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed arches Stone Tumble suggesting Wall Collapse |

East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6) - locus 6004

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Figure 15

Figure 15The main stone tumble, locus 6004. View from SE. By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

|

VI+ VIII + |

| Collapsed arches | East complex (Sector 6000 aka Secteur 6) - locus 6004

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Plan of Jabal Khubthah

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The ortho-photography of structure excavated in Sector 6000 By N. Paridaens Tholbecq et al (2019) |

Figure 11

Figure 11Remains of both arches as collapsed on pavement 6011. Walls 6000/6001 and superstructure 6027 on the left side. View from the NW. By Z.T. Fiema Tholbecq et al (2019) |

|

VI+ |

References

Books and Articles

FOURNET & PARIDAENS 2018 T. Fournet & N. Paridaens, « Les Bains du Jabal Khubthah. La campagne d'octobre 2017 », In L. Tholbecq (Ed.),

Mission archéologique française à Pétra (Jordanie). Rapport des campagnes archéologiques 2017-2018, Bruxelles, Presses de 1'ULB, p. 93-116.

Tholbecq, L., et al. (2014). "The “high place” of Jabal Khubthah: new insights on a Nabataean-Roman suburb of Petra." Journal of Roman Archaeology 27: 374-391.

Excavation Reports