Beirut

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Beirut | English | |

| Bayrūt | Arabic | بيروت |

| Beyrouth | French | |

| Bērytós | Greek | Βηρυτός |

| Berytus | Latin | |

| Colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus | Latin | |

| Barut | French (Crusaders) | |

| Baruth | French (Crusaders) | |

| bēʾrūt | Phoenician | |

| Biruta | Akkadian cuneiform - Amarna letters |

Beirut has a long history of occupation starting in

prehistorical times. During the Byzantine period, Beirut was known as Berytus where it was

renowned in the Roman world as a commercial center but most especially for its school of law,

which flourished from the third to the sixth centuries CE.

(

Issam Ali Khalifeh in Meyers, 1997).

The Beirut Quake of 551 CE

apparently caused the city to shrink in size. Archaeological excavations in the port area of Beirut where the old

Roman/Byzantine city was located have been limited.

Beirut is the capital of Lebanon , located on the Mediterranean coast (33°54' N , 35°3o' E). The city's ancient name was Biruta and, in the classical period, Berytus. Th e name is generally thought to b e derived from the common Semitic word for "well" or "pit" —in Akkadian, burtu; Hebrew, be'er; Arabic, bir. Biruta is a plural form.

Berytus was renowned in the Roman world as a commercial center but most especially for its school of law, which flourished from the third to the sixth centuries CE. The earthquake of 551 CE devastated the city. In turn the medieval city fell into ruins, but its scattered granite columns impressed the Persian traveler Nasr-i-Khusraw, who visited the city in 1047. The early western visitors, Henry Moundrell (1697), Richard Pococke (early eighteenth century), F. B. Spilsbury (1799), and William Thomson (1870), all realized that the scattered remains were the ruins of Roman public buildings.

In 1968, the Department of Antiquities commissioned Haroutine Kalayan to excavate certain monuments in Beirut.

- An extensive Roman bath near the Grand Serail, with a large cistern and rooms decorated with frescoes were uncovered and partly restored.

- A Roman defensive tower that had been reused in the medieval period

- A stretch of a Roman street complete with its pavement, columns, capitals, and an architrave in the center of Parliament Square

- A second Roman bath and part of an important municipal building (a basilica?) that probably covers the Decumanus Maximus

In 1977, when the possibility of reconstructing the modern city was being studied, Ibrahim Kawkabani, under auspices of the Lebanese Department of Antiquities, and J. D. Forest, from the Institut Francais d'Archeologie du Proche Orient, undertook a series of soundings to look for the city's ancient law school (see above). The work stopped with the onset of Lebanon's civil war. Twenty soundings were made, producing finds from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Mamluk periods. The material culture unearthed included pottery jars, lamps, and figurines, stamped Rhodian and other jar handles, carved bone objects; metal weights, rings, and handles; sculptured and inscribed reliefs, mortars, and capitals; and weaving utensils. Glass, coins, and gold jewelry, mainly from the Byzantine period, were also recovered but remain unpublished.

In 1977 and 1982, several attempts to reconstruct and restore modern Beirut's central business district were stalled by security considerations. In 1983 and 1984, reconstruction and restoration went forward at a considerable pace. A symposium called Beirut of Tomorrow, held at the American University of Beirut in 1983, called for the protection of historic monuments and for attempts to explore the ancient tell of Beirut. UNESCO experts Ernst Will and Rolf Hachmann were invited to the city in 1983 as consultants.

Early in 1993, UNESCO consultants Philippe Marquis, John Schofield, and Jean Paul Thalmann were contracted to work with the Council for Development and Restoration and the Department of Antiquities. On 10 September 1993, work was begun in downtown Beirut in collaboration with teams from the Lebanese University, the American University of Beirut, Britain, France , the Netherlands, and Italy, and the Royal Museum of Belgium. Five soundings were dug in a three-month period in the downtown area, with the objective of exploring the limits of the ancient town. The teams worked during 1994 and 1995 in and around the ancient town in an area of about 500,000 sq m, expanding the number of soundings to find the Prehistoric, Canaanite, Phoenician, Roman, and medieval cities. Archaeological rescue operations accompanied the construction in the downtown area and will continue to do so.

- Fig. 2 Excavation Areas

in Beirut's city center city center from Mordechai (2020)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Excavations in Beirut's city centre, 1993-1999 (after Mikati, The Creation [cit. n. 12], p. 282)

Mordechai (2020) - Fig. 3 Lebanese University

Site from Saghieh-Beidoun (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Lebanese University Site

Mordechai (2020) - Fig. 1 Suggested Location

of ancient Beirut from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Early archaeological surveys tended to suggest that the ancient city lay in an area between the present port seaboard, delimited by rue Foch to the east, rue Allenby to the west and the place de l’Etoile to the south (Renan, 1864; Che´hab, 1939; Mouterde, 1942–1943; Lauffray, 1944–1945, 1946–48; de Vaumas, 1946; Mouterde and Lauffray, 1952; Davie, 1987).

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 7 BEY archaeological

sites from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Location of BEY archaeological sites discussed in the text (base map from Curvers and Stuart, 2004).

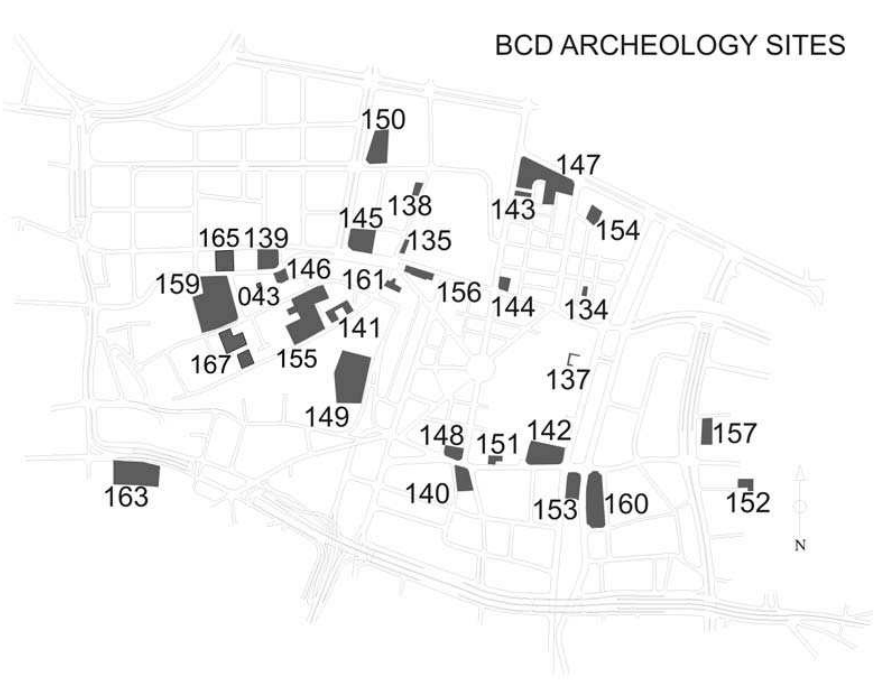

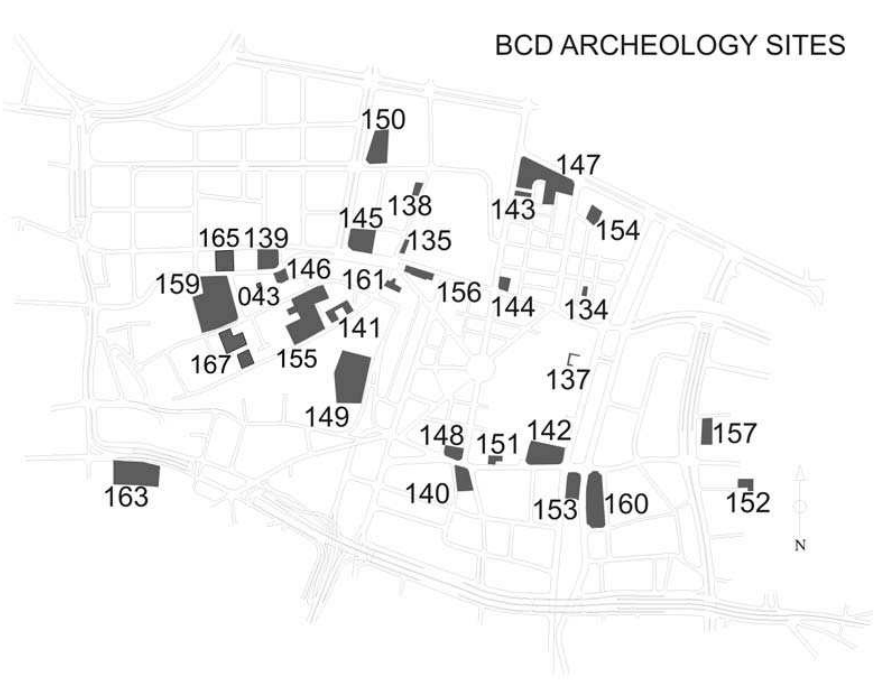

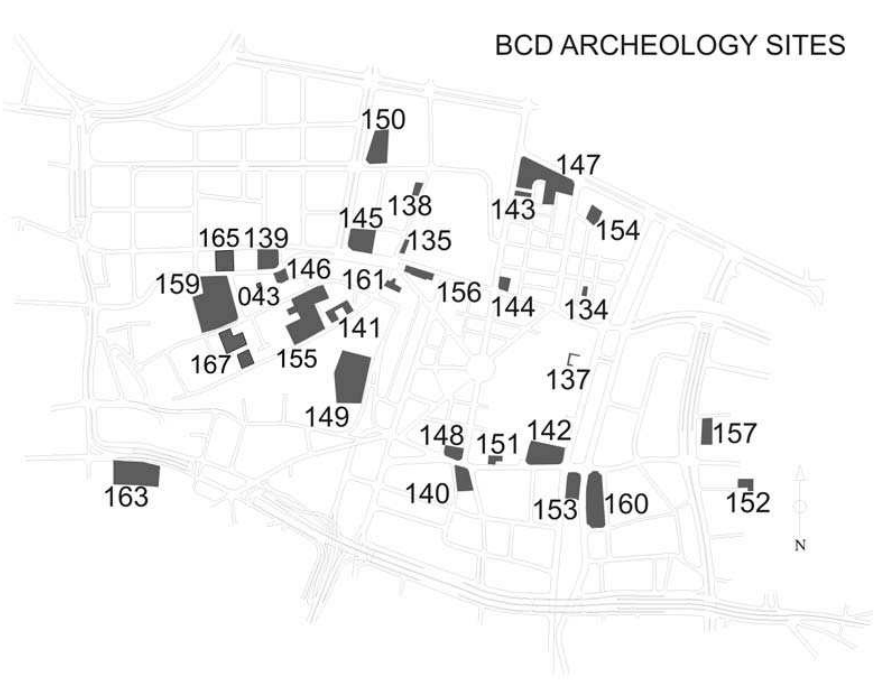

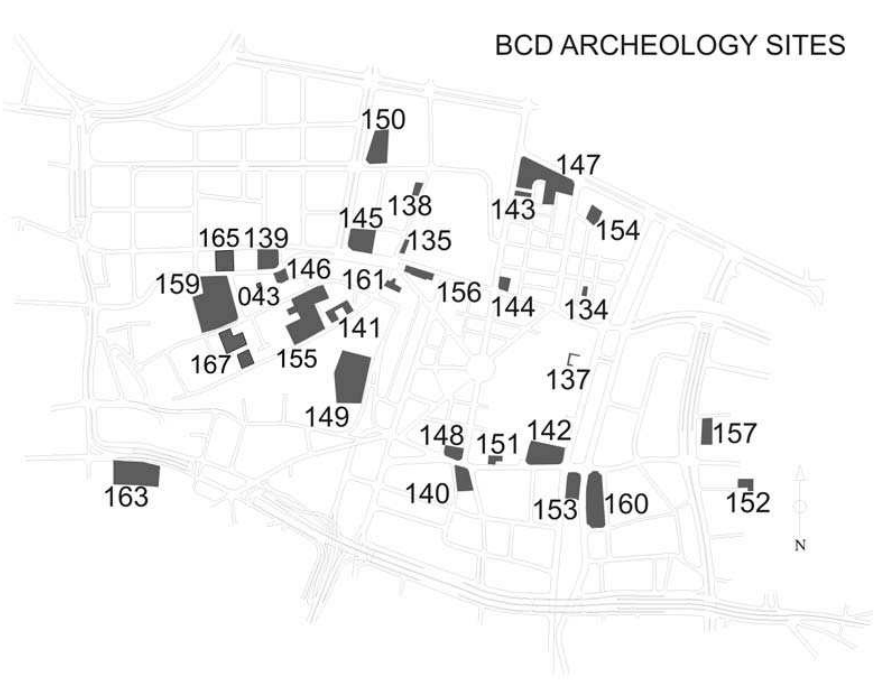

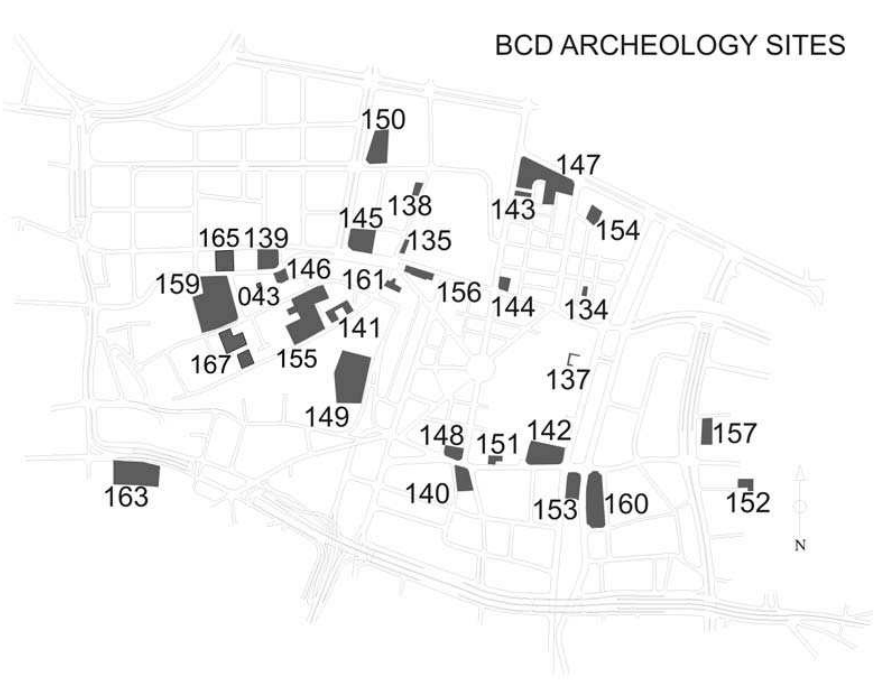

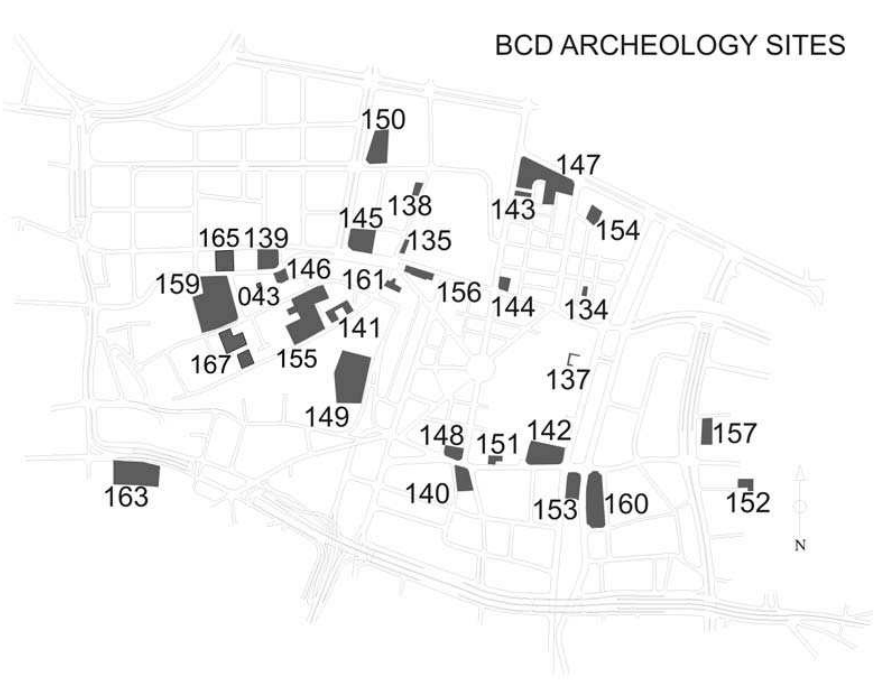

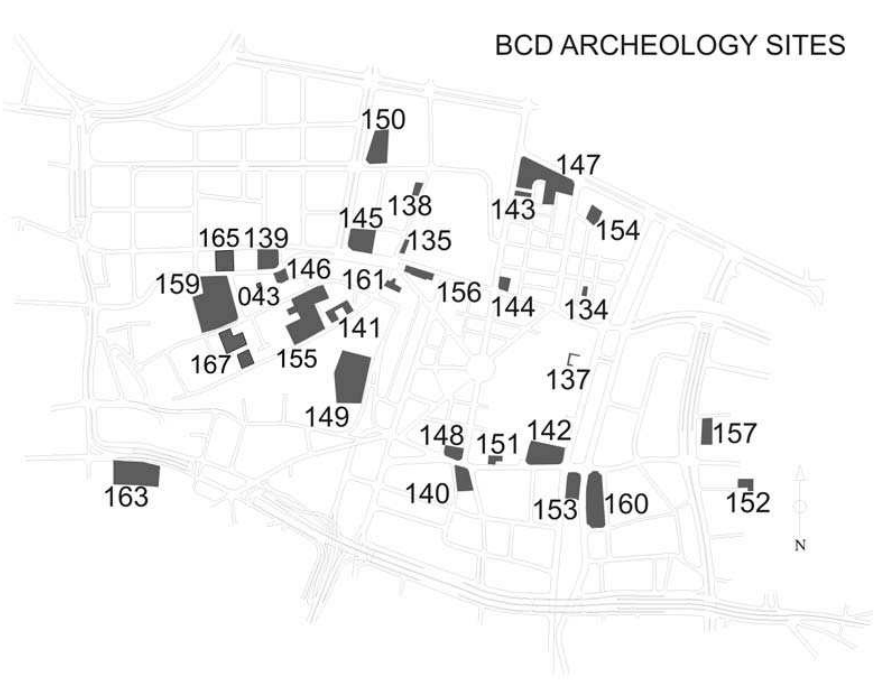

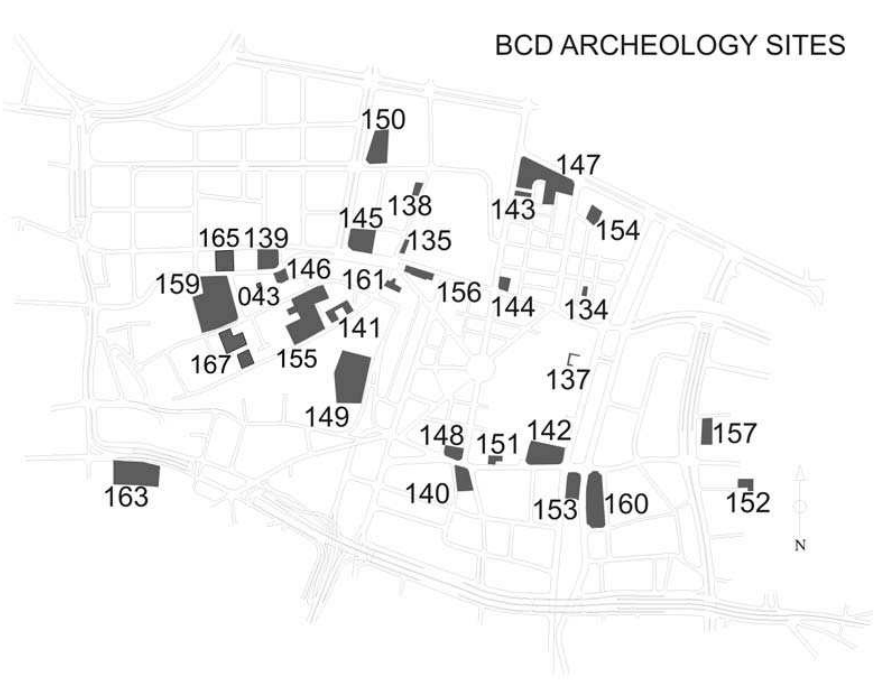

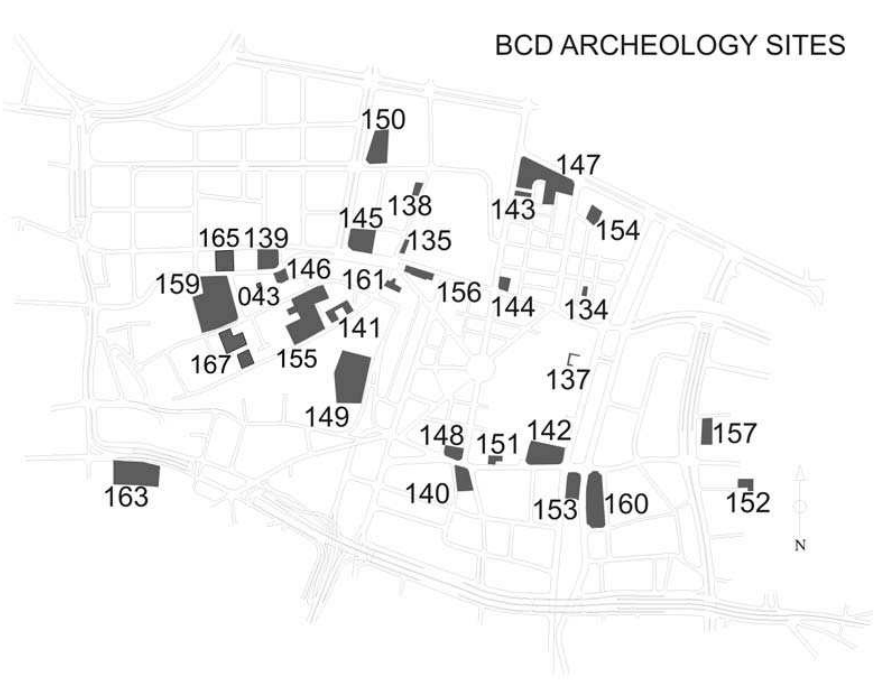

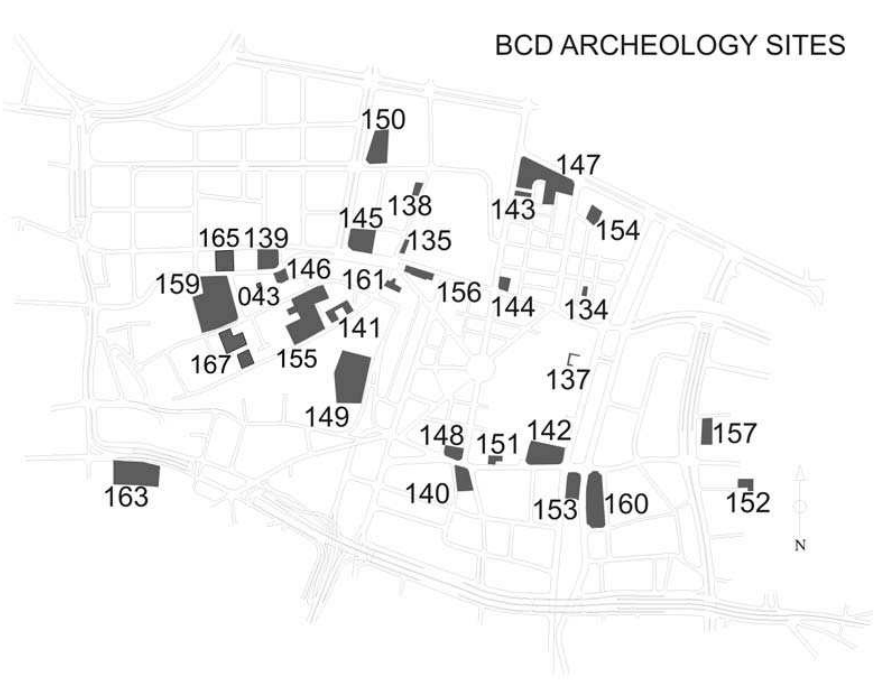

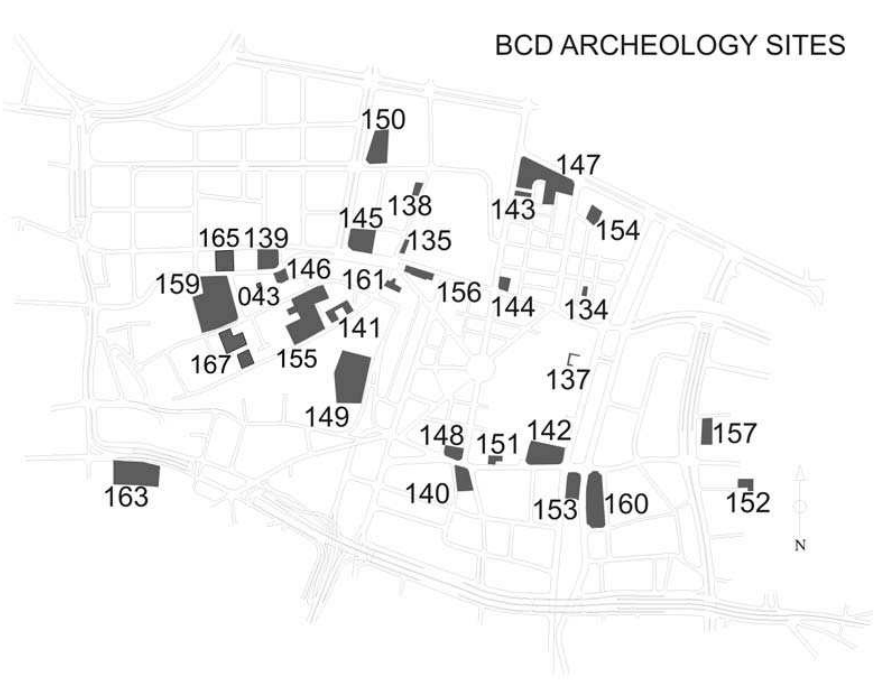

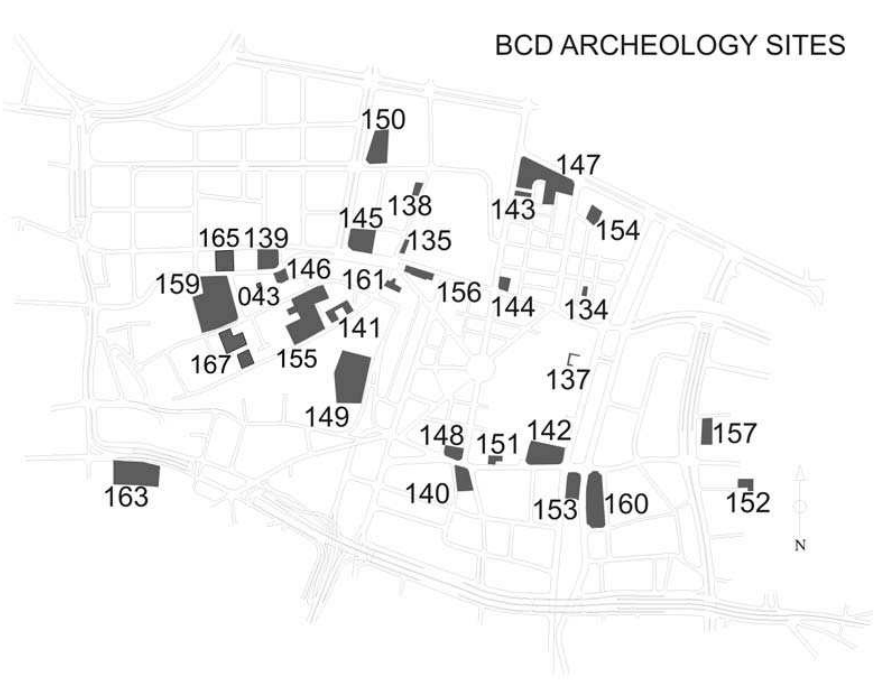

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 1 BCD archaeological

sites from Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location of archeological sites (1999-2006)

Curvers et al (2007) - Fig. 6 General Plan of

Berytus in Period VIIB-C (the Classical Period - 300 BCE - 800 CE) from Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 6

Period VIIB-C: General Plan of Berytus

Legend

- Castle cliffs (BEY 003, 131)

- Ras Medawer

- Ras Chamiyeh

- Decumanus Maximus East (BEY 133, 142, 152, 162)

- Decumanus Maximus West (BEY 052, 148)

- Cardo Maximus South (BEY 004, 155, 089)

- Cardo Maximus North (BEY 012, 031, 087.119, 126, 127)

- Imperial Thermae (BEY 045, 088, 102, 103, 126, 128)

- Serail Thermae (BEY 016, 117, 122)

- Hippodrome (BEY 072, 155, 159. 167)

- Temple of Fortuna (?) (BEY 004)

- Temple of Jupiter Heliopotanus (?) (BEY 140)

- Episcopal Palace (BEY 113, 158)

- Eastern Forum (BEY 158)

- Central Forum (BEY 009)

- Sport clubs of different factions (BEY 043, 139, 146, 159)

- Sacred space (BEY 159)

- Mosaic Building (BEY 159)

- Eastern Harbor

- Western Harbor (BEY 007, 049, 143, 147)

- Southeastern Thermae (BEY 094, 160)

- Serail Cliff shops (BEY 156)

- Glass Tank Furnaces >> Potter’s Kilns (BEY 015)

(based on Du Mesnil du Buisson 1921; Collinet 1925; Lauffray 1944-5; Davie 1987; Asmar 1998; Perring 2003; Marquis 2004; Curvers and Stuart 2004; Saghieh-Beydoun 2005)

Curvers et al (2007) - Fig. 11 Port of Beirut

from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

5000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004).

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 4 Port of Beirut

from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004)

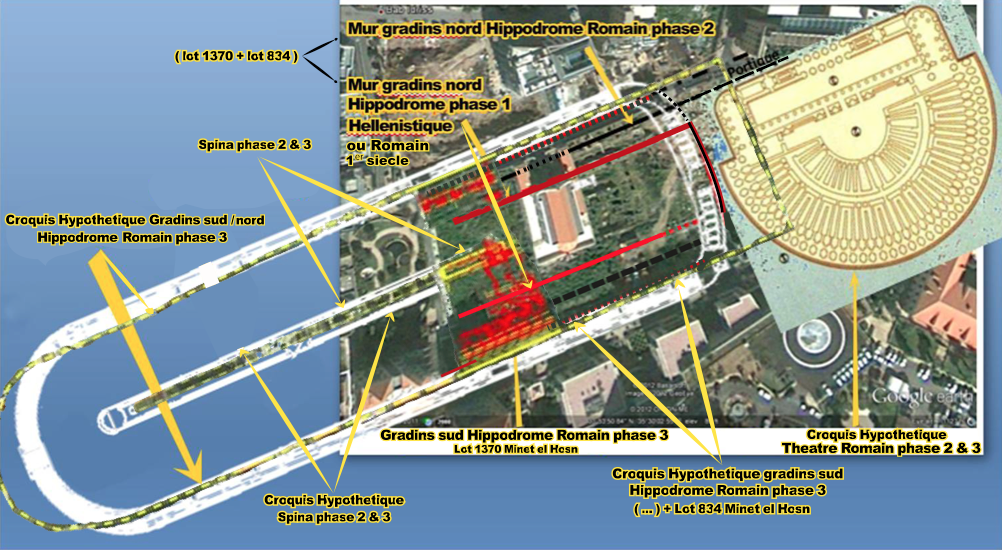

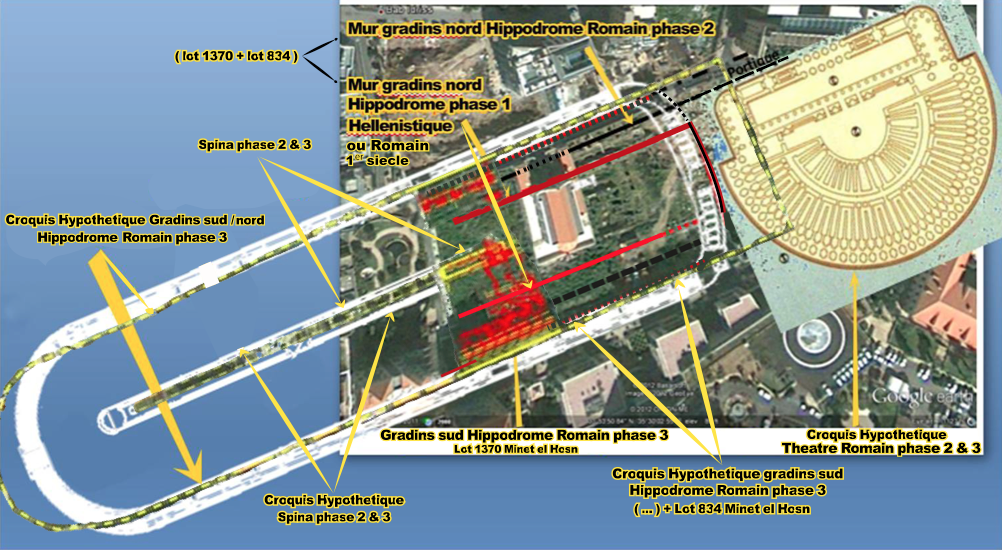

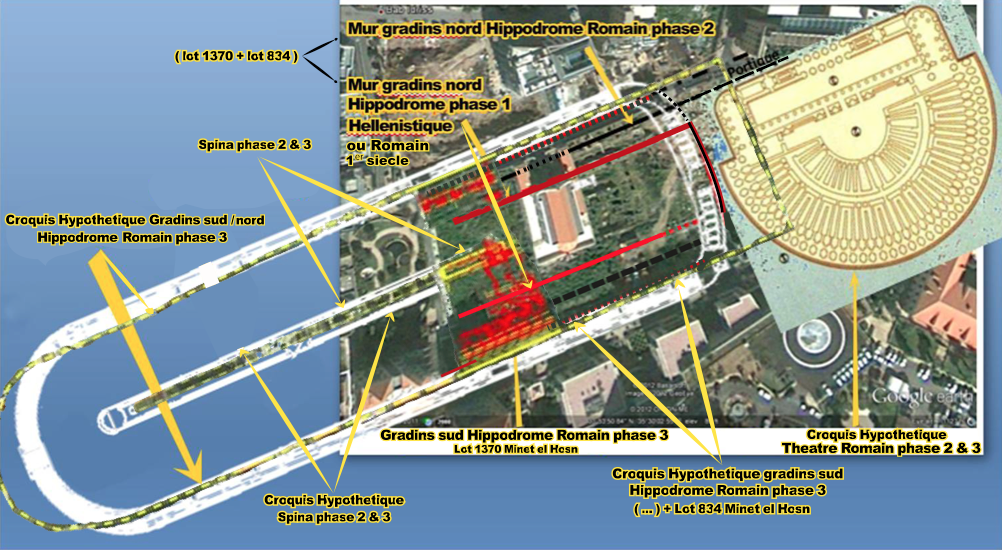

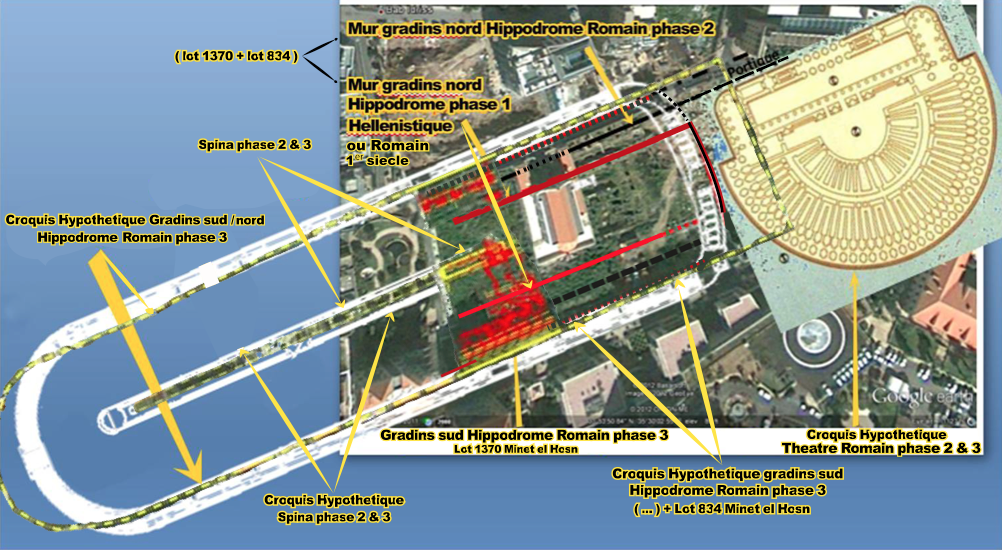

Marriner et al (2008) - Beirut Hippodrome

from Beirut Report

Beirut Hippodrome

Beirut Hippodrome

Beirut Report

- Fig. 2 Excavation Areas

in Beirut's city center city center from Mordechai (2020)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Excavations in Beirut's city centre, 1993-1999 (after Mikati, The Creation [cit. n. 12], p. 282)

Mordechai (2020) - Fig. 3 Lebanese University

Site from Saghieh-Beidoun (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Lebanese University Site

Mordechai (2020) - Fig. 1 Suggested Location

of ancient Beirut from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Early archaeological surveys tended to suggest that the ancient city lay in an area between the present port seaboard, delimited by rue Foch to the east, rue Allenby to the west and the place de l’Etoile to the south (Renan, 1864; Che´hab, 1939; Mouterde, 1942–1943; Lauffray, 1944–1945, 1946–48; de Vaumas, 1946; Mouterde and Lauffray, 1952; Davie, 1987).

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 7 BEY archaeological

sites from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Location of BEY archaeological sites discussed in the text (base map from Curvers and Stuart, 2004).

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 1 BCD archaeological

sites from Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location of archeological sites (1999-2006)

Curvers et al (2007) - Fig. 6 General Plan of

Berytus in Period VIIB-C (the Classical Period - 300 BCE - 800 CE) from Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 6

Period VIIB-C: General Plan of Berytus

Legend

- Castle cliffs (BEY 003, 131)

- Ras Medawer

- Ras Chamiyeh

- Decumanus Maximus East (BEY 133, 142, 152, 162)

- Decumanus Maximus West (BEY 052, 148)

- Cardo Maximus South (BEY 004, 155, 089)

- Cardo Maximus North (BEY 012, 031, 087.119, 126, 127)

- Imperial Thermae (BEY 045, 088, 102, 103, 126, 128)

- Serail Thermae (BEY 016, 117, 122)

- Hippodrome (BEY 072, 155, 159. 167)

- Temple of Fortuna (?) (BEY 004)

- Temple of Jupiter Heliopotanus (?) (BEY 140)

- Episcopal Palace (BEY 113, 158)

- Eastern Forum (BEY 158)

- Central Forum (BEY 009)

- Sport clubs of different factions (BEY 043, 139, 146, 159)

- Sacred space (BEY 159)

- Mosaic Building (BEY 159)

- Eastern Harbor

- Western Harbor (BEY 007, 049, 143, 147)

- Southeastern Thermae (BEY 094, 160)

- Serail Cliff shops (BEY 156)

- Glass Tank Furnaces >> Potter’s Kilns (BEY 015)

(based on Du Mesnil du Buisson 1921; Collinet 1925; Lauffray 1944-5; Davie 1987; Asmar 1998; Perring 2003; Marquis 2004; Curvers and Stuart 2004; Saghieh-Beydoun 2005)

Curvers et al (2007) - Fig. 11 Port of Beirut

from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

5000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004).

Marriner et al (2008) - Fig. 4 Port of Beirut

from Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004)

Marriner et al (2008) - Beirut Hippodrome

from Beirut Report

Beirut Hippodrome

Beirut Hippodrome

Beirut Report

- from Curvers et al (2007)

| Period | Dates (CE) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | - 10,000 BCE | Paleolithic |

| II | 10,000 - 6000 BCE | Pre-pottery Neolithic |

| III | 6000 - 4500 BCE | Pottery Neolithic |

| IV | 4500 - 3000 BCE | Chalcolithic |

| V | 3000 - 1200 BCE | Bronze Age |

| VI | 1200 - 300 BCE | Iron Age |

| VII | 300 BCE - 800 CE | Classical |

| VIII | 800 - 1700 CE | Medieval |

| VII | 1840 - 1920 CE | The great reconstruction of Beirut in the 19th century |

| VIII | 1920 - 1975 CE | The remains of pre-war Beirut |

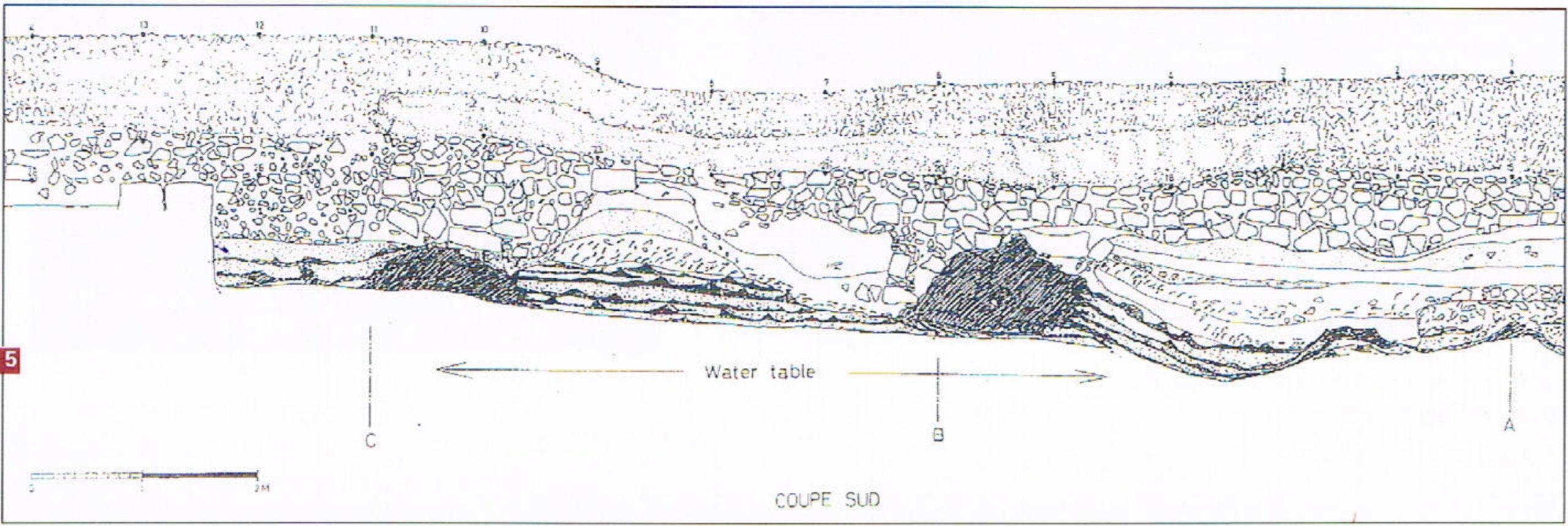

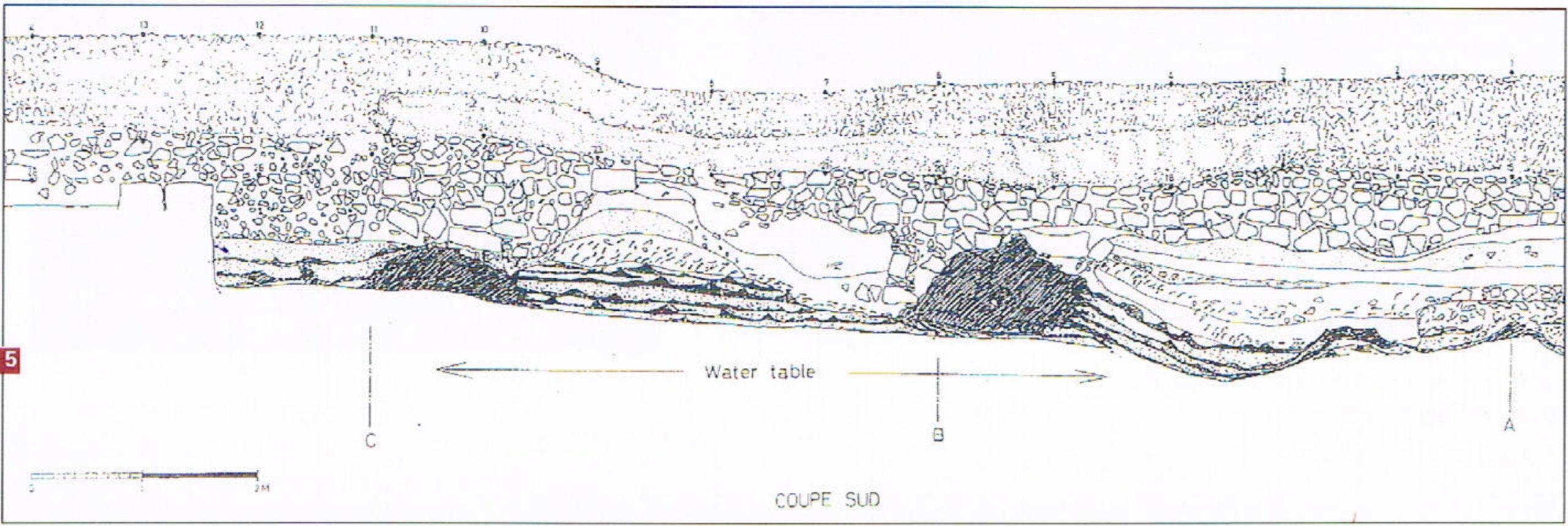

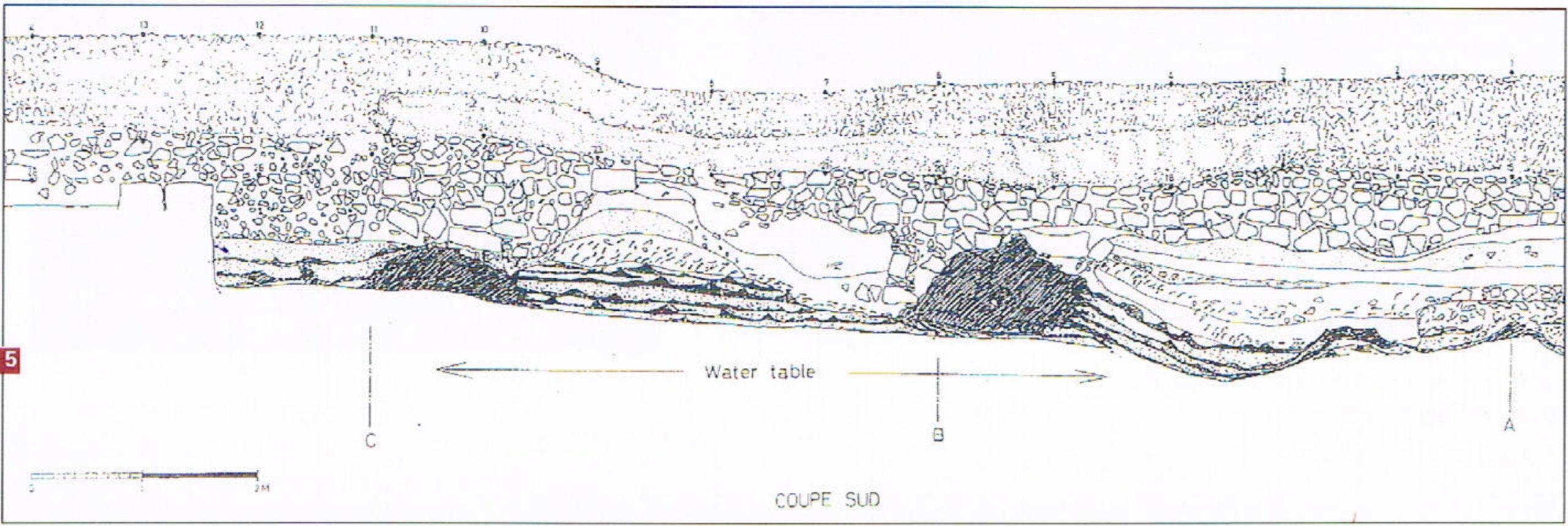

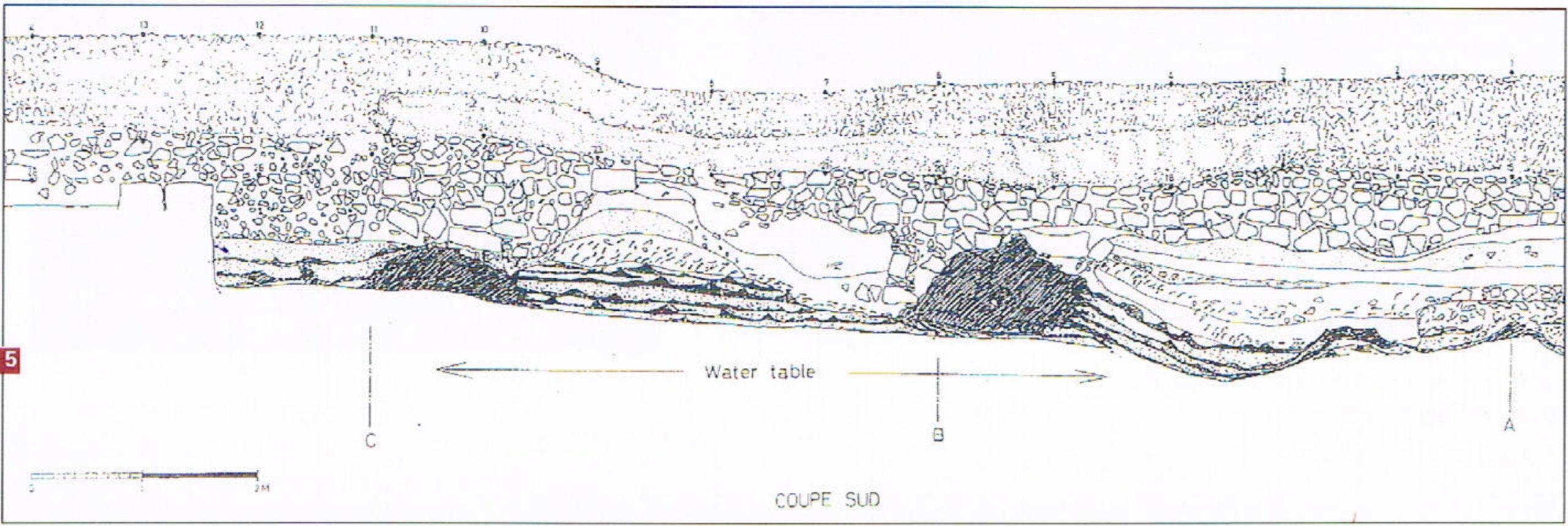

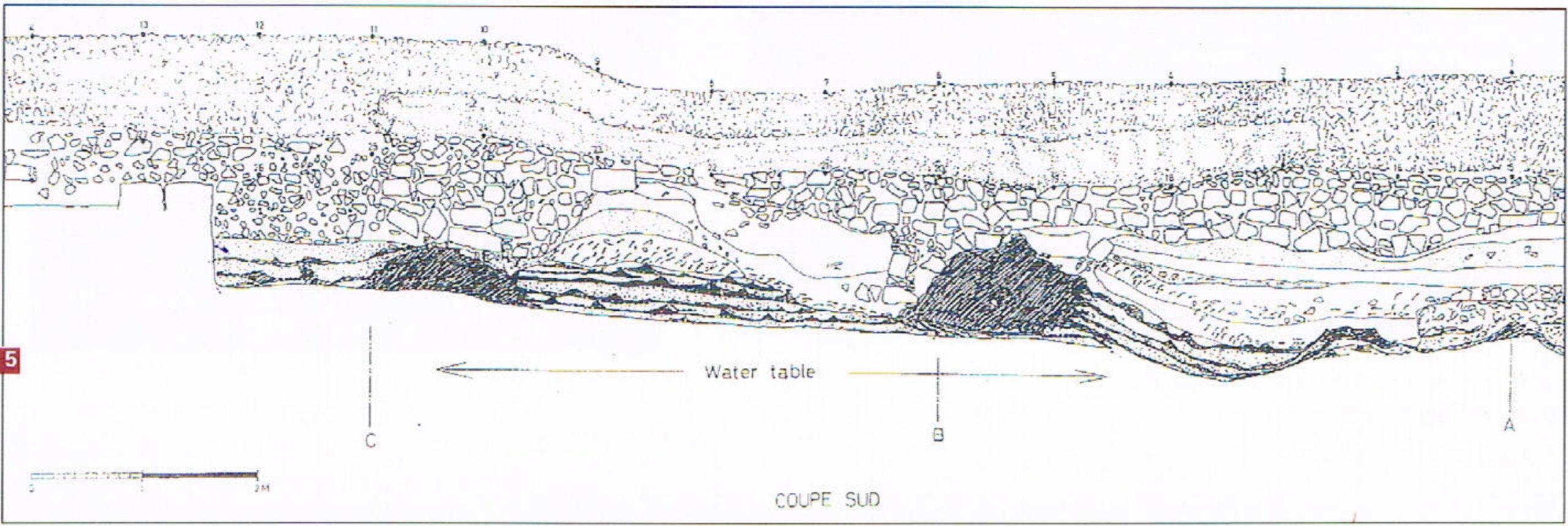

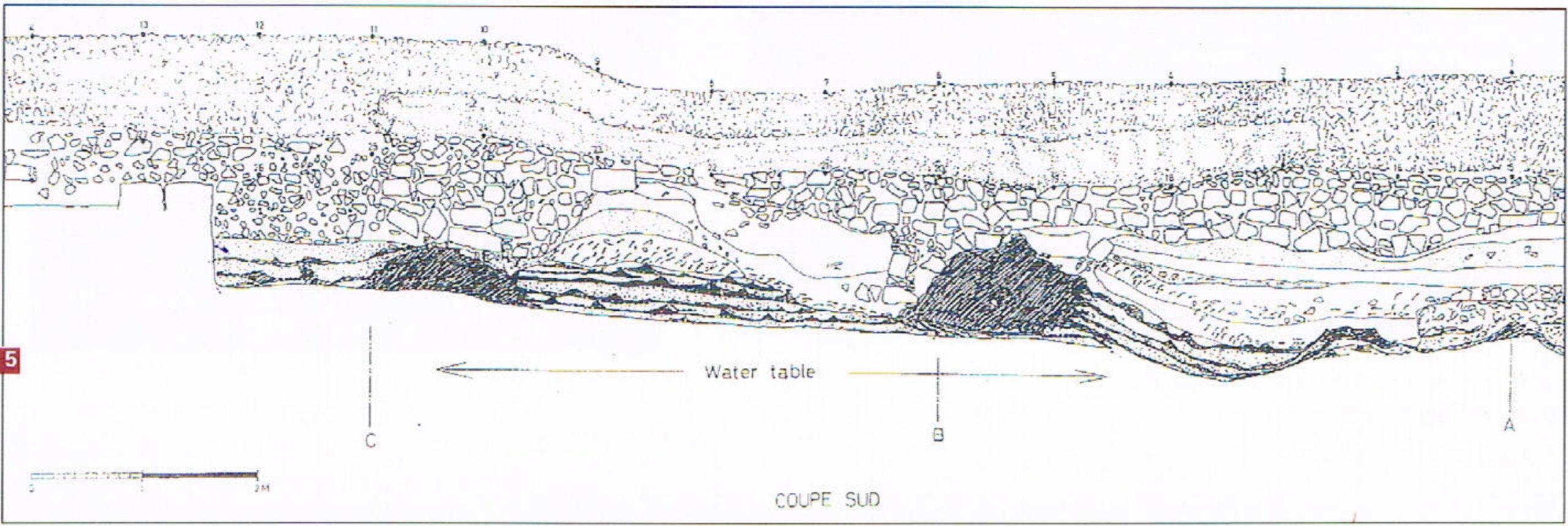

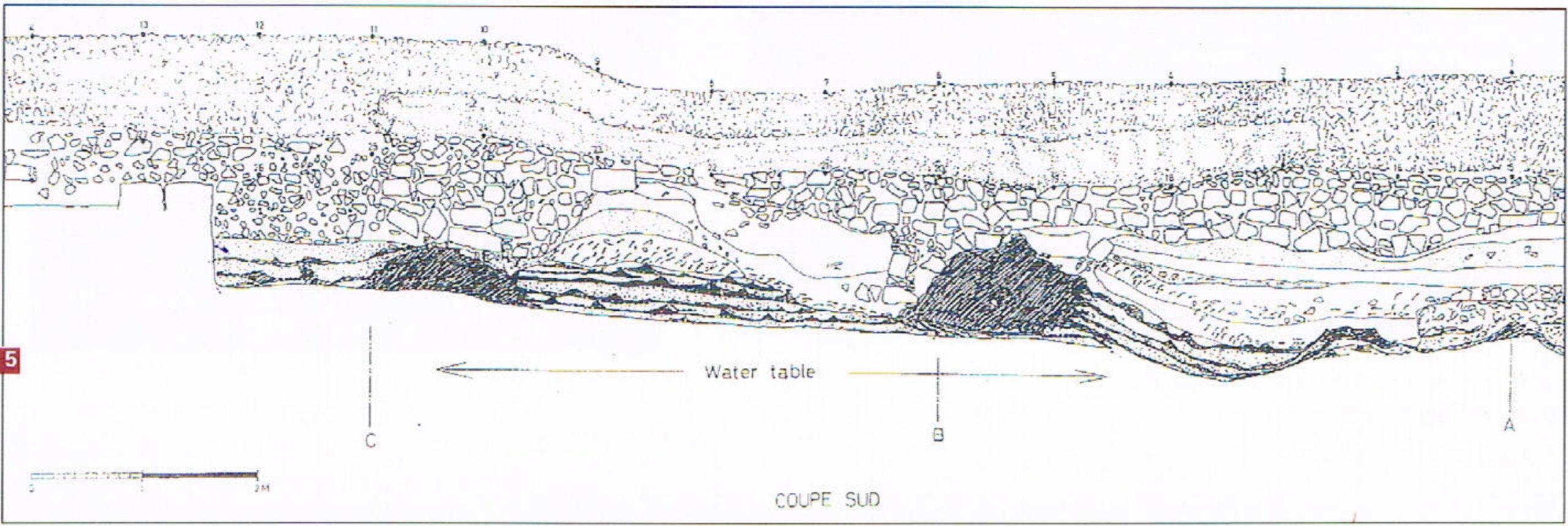

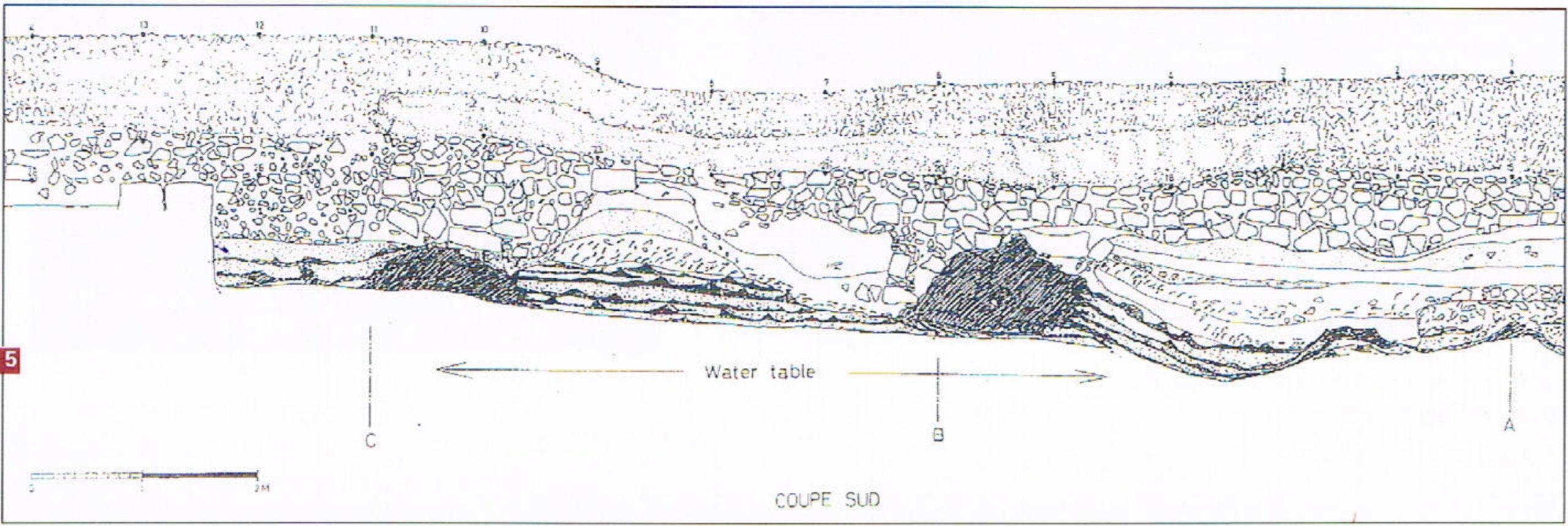

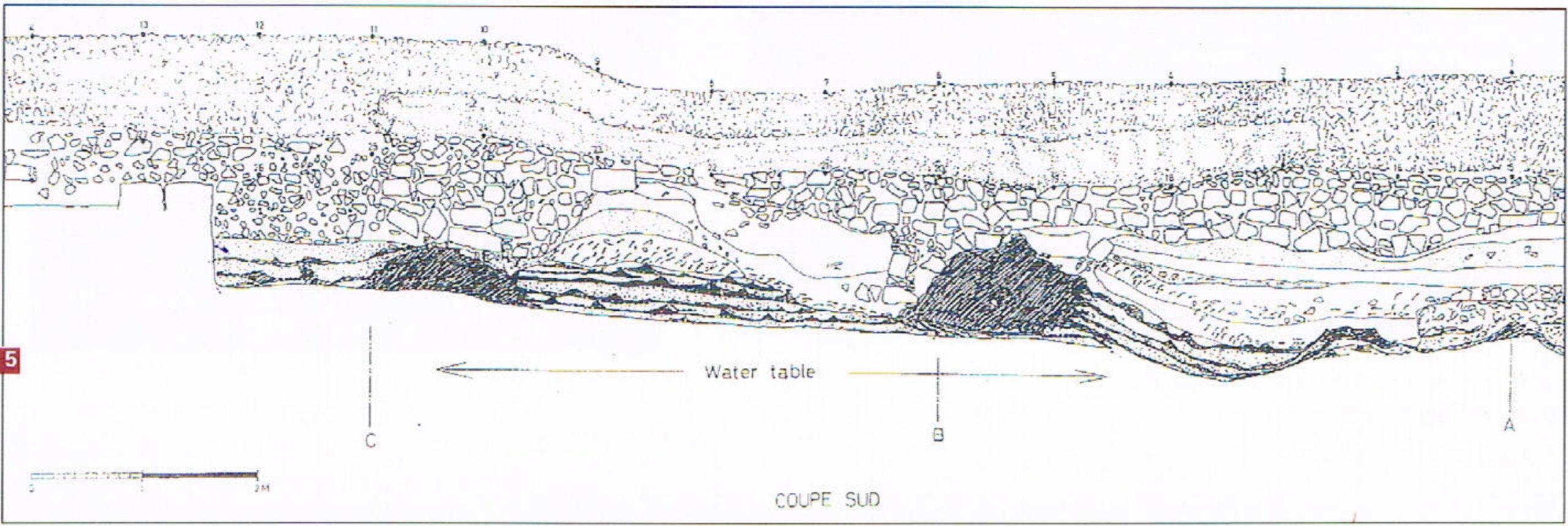

Figure 5

Figure 5South Section

JW: Flame features are drawn in the bottom layer of the section.

Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

In Sector BEY 004 (Lebanese University Site ?), Saghieh-Beydoun (1997) discovered some soft sediment liquefaction features known as flame features at the base of what appears to be be a destruction layer or debris flow deposit. This deposit may be dated to the mid 6th century CE - the date of the images above are not entirely clear in the article and I don't currently have access to the report. The flame features show up at the bottom of the drawing above. A photograph of this or a nearby section (below) also shows the flame features.

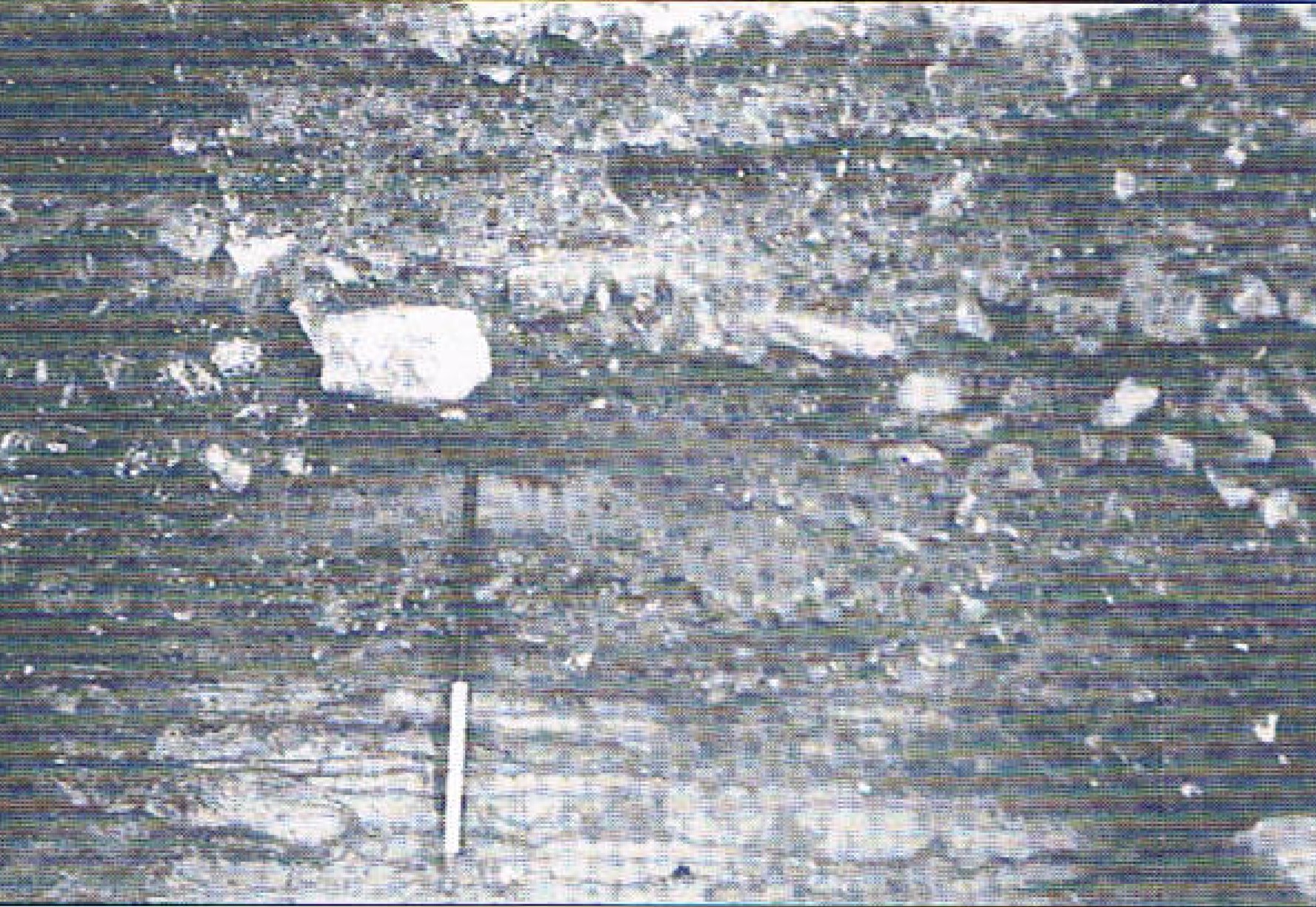

Figure 4

Figure 4Seismites and Liquefactions

JW: Flame features are visible at the very bottom of the section (e.g. from the white part of the pole downward).

Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

Flame features are diagnostic of pore fluid overpressures which are commonly caused by liquefaction during earthquakes. Their presence at the bottom of the debris layer may suggest a tsunami debris flow deposit that was then agitated by seismic shaking that then created the liquefaction features supporting observations by John of Ephesus and Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre that the tsunami preceded the earthquake suggesting further, as noted by Mordechai (2020) that the main earthquake struck after a powerful foreshock.

Mordechai (2020) surveyed archeoseismic evidence in Beirut:

A late antique layer of destruction, followed by fire in some cases, was found in several excavation sites in the city and was attributed to the 551 earthquake based on several pieces of evidence.[54] One archaeologist described how a diagnostic sounding revealed the earthquake’s ‘horrors in an archaeological inferno over the whole [single] excavated area’ through a layer of destruction between 0.75m and 1.00m thick.[55] This layer, however, was uneven and much thinner in other areas. Other teams asserted that the buildings in their site did not collapse immediately – as evident from the absence of smashed collections of pottery and household goods.[56]Hall (2004) noted that:Footnotes[54] The excavations revealed objects that were buried in the debris such as a wrapped coinroll (see below), a hanging bronze polykandelon and human and animal remains near a collapsed wall, and another group of coins. For the objects, see respectively Mikati & Perring,‘Metropolis to ribat’ (cit. n. 4), pp. 47–49, Perring, ‘Excavations in the Souks’ (cit. n. 41), pp.21–23

, and M. Steiner, ‘The Hellenistic to Byzantine souk: results of the excavations at BEY 011’, ARAM 13–14 (2001–2002), pp. 113–127. Other teams were uncertain whether the destruction layer was to be dated to the sixth or seventh century. See P. Arnaud, E. Llopis & M. Bonifay,‘Bey 027 Rapport préliminaire’, BAAL 1 (1996), pp. 98–134, at p. 109.

[55] Saghieh, ‘Bey 001 & 004’ (cit. n. 46), p. 40.. M. Saghieh-Beydoun, ‘Evidence for earthquakes in the current excavations of Beirut city centre’, [in:] C. Doumet-Serhal (ed.), Decade: A Decade of Archaeology and History in the Lebanon, Beirut 2004, pp. 280–285, at p. 284 later reported finding soil liquefaction, an earthquake-related phenomenon, but did not attribute it to a dated seismic event.

[56] For layer of destruction, see for example Figure 6 in L. Badre, ‘The Greek Orthodox cathedral of Saint George in Beirut, Lebanon: The archaeological excavations and crypt museum’, JEMAHS 4 (2016), pp. 72–97, at p. 78.. For buildings not collapsing, see D. Perring et al., ‘Bey 006, 1994–1995: The souks area interim report of the AUB Project’, BAAL 1 (1996), pp. 176– 206, at pp. 196–198. K. Butcher & R. Thorpe, ‘A note on excavations in central Beirut 1994– 1996’, JRA 10 (1997), pp. 291–306, at p. 299, assert that ‘evidence for earthquake damage on the Souks site is virtually absent...’, and M. Heinz & K. Bartl, ‘Bey 024 “Place Debbas” preliminary report’, BAAL 2 (1997), pp. 236–257, at p. 256, similarly assert that ‘traces of violent destruction (earthquake) were not visible’.

Some archeological evidence has been interpreted to suggest rebuilding on a scale not quite the match of the previous construction (compare Agathias above). Lauffray has found columns of mismatched colors in a building he considers either a church or a basilica. He thinks these columns may represent replacement work after the earthquake. It is notable that Zacharias in his description of the church of Eustathius insists very strongly that the original columns were of purest white and were carefully matched.[115] When summing up the archeological evidence for Berytus, Lauffray thought that some restorations were made to the civic basilica in the sixth century AD. Lauffray also suggested that after the earthquake some of the baths and certain parts of the porticos of the streets were restored. Lauffray notes the difficulty of securely identifying the churches and some other buildings.Footnotes[115] Lauffray (1944–6) 62, referring to a colonnade indicated by five column bases.

Marriner et al (2008) reported on 20 cores taken in Beirut's buried ancient harbor; none of which contained apparent tsunamites. However, the tsunami may have left evidence in other parts of the city. Some of their discussion regarding tsunamogenic evidence is reproduced below:

Excavations undertaken in Beirut's harbour by Curvers et al. have revealed the presence of tree branches and considerable amounts of unabraded Roman pottery and rubble in 6-7th century AD layers (Curvers, personal communication). Surveys in the Ottoman harbour have unearthed harbour muds and silts which lie unconformably above sea-scoured bedrock (Curvers and Stuart, 2004). These have been attributed to tsunami action and indirectly infer considerable damage to the city's seaport infrastructure. This archaeological evidence, coupled with the stratigraphic data, support major changes in the port's configuration at this time. At no point during the Islamic and medieval periods do we record such a well-protected harbour. In light of this, there appears to be a clear link between the retraction of the Byzantine Empire to its Anatolian core and the catastrophic destruction of many parts of Beirut, including its harbour area, during the 551 AD earthquake and tsunami.Salamon et al. (2024:Section 1.3) summarized 551 CE tsunamigenic evidence in Beirut as follows:

... Although sedimentary traces of the tsunami impacts are not observed in the cores, recent excavations suggest that the ancient sources did not exaggerate in their description of the archaeological destruction caused by the event (Curvers and Stuart, 2004). New research has yielded closely dated stratigraphic sequences at a number of dig sites that unequivocally corroborate the widespread earthquake damage (Elayi and Sayegh, 2000; Curvers and Stuart, in press). In the aftermath, Beirut underwent altering patterns of trade, production and consumption. The archaeology also shows that many parts of the city were left in partial ruin or even abandoned, with limited evidence for reconstruction. Mikati and Perring (2006) present a model of 'continuity' but degradation of urban infrastructure at post-earthquake Beirut. Dating of raised shorelines north of Beirut confirms uplift of 50-80 cm (Morhange et al., 2006).

We focused on Marriner et al. (2008, and references therein), who conducted extensive geoarchaeological investigations in the area of the ancient harbor of Beirut and integrated a wealth of information from previous studies. They unearthed and discovered unique findings dated to the Byzantine and later periods. A notable finding is the transition from fine-grained to coarser-grained sediments, which is usually associated with a partial or total abandonment of harbors and/or economic and political decline. They also uncovered sea-scoured bedrock that can be attributed to erosion due to strong tsunami currents. In addition, they noted the spread of ruins, the relative absence of seaport infrastructure, partial abandonment, and limited rebuilding across the city area of Beirut at that time. Furthermore, these authors were able to reconstruct the location of the Romano-Byzantine harbor coastline of Beirut at the time of the earthquake (Fig. 11 dashed blue line, in Marriner et al. 2008). They also inferred that westward and eastward, the harbor coastline appeared to merge with the pre-1840 coastline, which has not changed much since antiquity. Overall, Marriner et al. (2008) concluded that these discoveries echo a catastrophic event, most likely the 551 earthquake and tsunami.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Beirut |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| flame features at the bottom of a collapse layer | South section BEY 004 (Lebanese University Site ?)

Figure 3

Figure 3The Lebanese University Site Mordechai (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5South Section JW: Flame features are drawn in the bottom layer of the section. Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

Figure 4

Figure 4Seismites and Liquefactions JW: Flame features are visible at the very bottom of the section (e.g. from the white part of the pole downward). Saghieh-Beydoun (2004) |

|

| Collapse layer | Various locations (?) including South section BEY 004 (Lebanese University Site ?)

Figure 3

Figure 3The Lebanese University Site Mordechai (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5South Section JW: Flame features are drawn in the bottom layer of the section. Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

Figure 4

Figure 4Seismites and Liquefactions JW: Flame features are visible at the very bottom of the section (e.g. from the white part of the pole downward). Saghieh-Beydoun (2004) |

|

| Fallen Columns (inferred) | ? |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| tree branches and considerable amounts of unabraded Roman pottery and rubble in 6-7th century CE layers |

Beirut's harbour at one of the BCD sites (?)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Location of archeological sites (1999-2006) Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 11

Fig. 115000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004). Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004) Marriner et al (2008) |

|

|

| harbour muds and silts lying unconformably above sea-scoured bedrock | Ottoman harbour at one of the BCD sites (?)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Location of archeological sites (1999-2006) Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 11

Fig. 115000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004). Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004) Marriner et al (2008) |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Beirut |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| flame features at the bottom of a collapse layer indicating liquefaction | South section BEY 004 (Lebanese University Site ?)

Figure 3

Figure 3The Lebanese University Site Mordechai (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5South Section JW: Flame features are drawn in the bottom layer of the section. Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

Figure 4

Figure 4Seismites and Liquefactions JW: Flame features are visible at the very bottom of the section (e.g. from the white part of the pole downward). Saghieh-Beydoun (2004) |

|

VII + |

| Collapse layer indicating collapsed walls | Various locations (?) including South section BEY 004 (Lebanese University Site ?)

Figure 3

Figure 3The Lebanese University Site Mordechai (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5South Section JW: Flame features are drawn in the bottom layer of the section. Saghieh-Beydoun (2004)

Figure 4

Figure 4Seismites and Liquefactions JW: Flame features are visible at the very bottom of the section (e.g. from the white part of the pole downward). Saghieh-Beydoun (2004) |

|

VIII + |

| Fallen Columns (inferred) | ? |

|

V + | |

| tsunami indicated by tree branches and considerable amounts of unabraded Roman pottery and rubble in 6-7th century CE layers |

Beirut's harbour at one of the BCD sites (?)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Location of archeological sites (1999-2006) Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 11

Fig. 115000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004). Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004) Marriner et al (2008) |

|

IX+ | |

| tsunami indicated by harbour muds and silts lying unconformably above sea-scoured bedrock | Ottoman harbour at one of the BCD sites (?)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Location of archeological sites (1999-2006) Curvers et al (2007)

Fig. 11

Fig. 115000 years of coastal deformation in Beirut’s ancient harbour. Note the progressive regularisation of the coastline from a natural indented morphology to an increasingly rectilinear disposition during later periods (base image: DigitalGlobe, 2006). Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004). Marriner et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Location of core sites at Beirut. Archaeological data from Elayi and Sayegh (2000) and Marquis (2004) Marriner et al (2008) |

|

IX+ |

Badre, L., ‘The Greek Orthodox cathedral

of Saint George in Beirut, Lebanon: The archaeological excavations and crypt museum’,

JEMAHS 4 (2016), pp. 72–97, at p. 78.

Butcher, K. and R. Thorpe, R. (1997) ‘A note on excavations in central Beirut 1994–

1996’, JRA 10 (1997), pp. 291–306

Curvers, Hans H. and Stuart, Barbara (2004)

“BCD Archeology Project 1994 – 2003: issues and results” in:

Claude Doumet-Serhal et al. Decade: A Decade of Archaeology and History in the Lebanon,

The Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum, London; Beirut: 248–265.

Curvers, Hans H. and Stuart, Barbara (2007) ” The BCD Archaeology Project, 2000–2006”

, Bulletin d’Archéologie et d’Architecture Libanaises 9: 189–221.

Lauffray (1944–6) Forums et monuments de Béryte BMB 7 62

Marriner, N., et al. (2008). "Geoarchaeology of Beirut's ancient harbour, Phoenicia." Journal of Archaeological Science 35(9): 2495-2516.

Marquis, Philip and Ortali-Tarazi, Renata (1996) « Bey 009 L’immeuble de la Banco di Roma ». Bulletin d’Archéologie et d’Architecture Libanaises 1:148–175.

Mordechai, L. (2020). "Berytus and the aftermath of the 551 earthquake." Studies in Source Criticism.

Perring, D. et .al. (1996) ‘Bey 006, 1994–1995:

The souks area interim report of the AUB Project’, BAAL 1 (1996), pp. 176– 206, at pp. 196–198.

Saghieh-Beydoun, M. (1997) Evidence of Earthquakes in the Current Excavations of Beirut City Centre. National Museum News, 5th issue, Spring 1997

Saghieh, M. (1996). "BEY 001 & 004 preliminary report." 1: 23-59.

Saghieh-Beydoun, M. (2004) ‘Evidence for earthquakes

in the current excavations of Beirut city centre’, [in:] C. Doumet-Serhal (ed.),

Decade: A Decade of Archaeology and History in the Lebanon, Beirut 2004, pp. 280–285

Badre, Leila. "The Historic Fabric of Beirut." In Beirut of Tomorroio,

edited by Friedrich Ragette, pp . 65-76 . Beirut, 1983. Historical outline and review of archaeological remains unearthed to the date of

publication.

Forest, J. D . "Fouilles a municipalite de Beyrouth, 1977. " Syria 59

(1982): 1-26. Primarily the results of soundings that produced Roman, Byzantine, and later material.

Jidejian, Nina. Beirut through the Ages. Beirut, 1973. Useful history of

Beirut.

Mouterde , Rene , and Jean Lauffray. Beyrouth ville romaine: Histoire et

monuments. Beirut, 1952. Helpful study of the history and archaeology of Beirut in the Roman period.

Mouterde , Rene. Regards sur Beyrouth; Phinicienne, hellenislique et romaine. Beirut, 1966. Good review of Beirut's historical and archaeological monuments and remains.

Saidah, Roger. "Archaeology in the Lebanon, 1968-1969. " Berytus 18

(1969): 119-142 . Useful information on archaeological activities in

the late 1960s.

Saidah, Roger. "The Prehistory of Beirut." In Beirut: Crossroads of Cultures, pp . 1-13 . Beirut, 1970. Good review of archaeological evidence

for the prehistoric periods.

Turquety-Pariset, Francoise. "Fouille de la municipalite de Beyrouth,

1977: Les objects." Syria 59 (1982): 27-76 . Good catalog of objects

from the Roman, Byzantine, and later periods.

Ward, William A. "Ancient Beirut." In Beirut: Crossroads of Cultures,

p p . 14-42 . Beirut, 1970. Uses the scant archaeological remains to

reconstruct the history of Beirut, with some freewheeling interpretations.