Ashdod-Yam

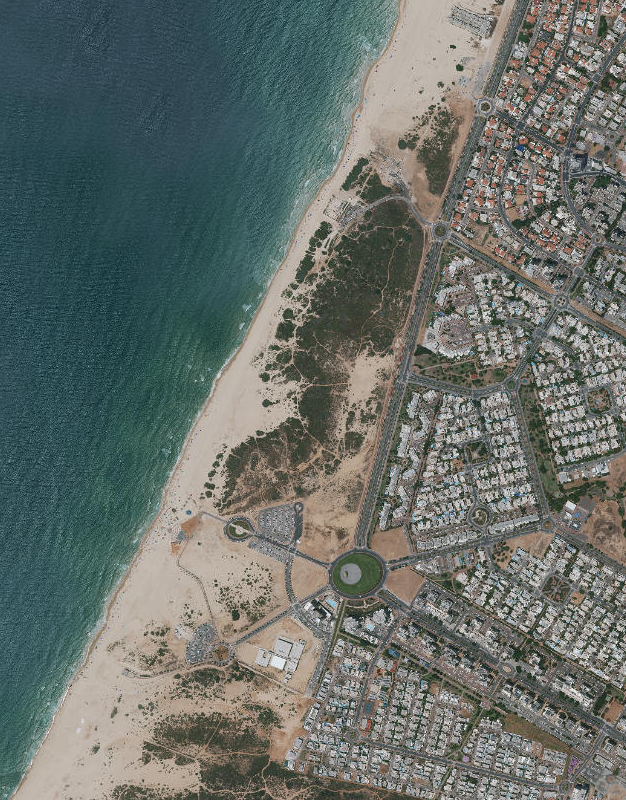

Aerial View of Ashdod-Yam (the beach area)

Aerial View of Ashdod-Yam (the beach area)Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable map

from www.govmap.gov.il

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Ashdod-Yam | Hebrew | |

| Azotus Paralios | Greek | |

| asdudi-immu | Assyrian | |

| aṯdādu | Late Bronze age Canaaanite | |

| Mahuz Azdud | Older Arabic | |

| Minat al-Qal'a | Contempory Arabic | |

| Castellum Beroart | French (Crusades) |

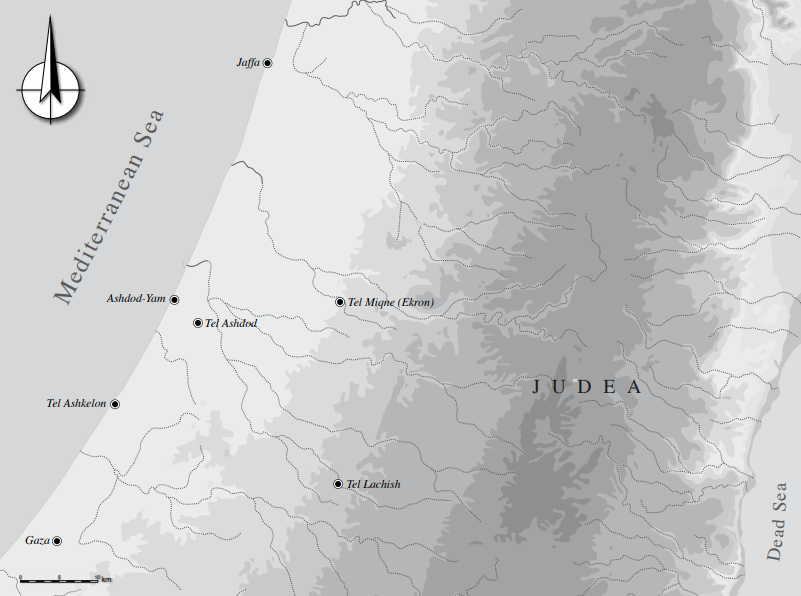

The site of Ashdod-Yam is on the Mediterranean coast about 5 km (3 mi.) southwest of Tel Ashdod, one of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, and about 2 km (1.2 mi.) south of modern Ashdod (map reference 1140.1314). Archaeological surveys carried out by this writer since 1940 revealed a large, semicircular, rampart-like structure in the southern part of the site.

Ashdod-Yam is mentioned only in documents from the time of Sargon II (742-705 BCE), in connection with his campaign against the kingdom of Ashdod in 713 BCE to depose the usurper who had seized rule in Ashdod. According to the documents, this usurper, called Iamani by Sargon, fortified three cities in the kingdom of Ashdod in great haste: Ashdod itself, Gath, and Ashdod-Yam. The last was evidently intended to serve as a rear base for the main city in times of danger. Because neither earlier nor later fortifications were discovered at the site, the uncovered wall and glacis (see below) are most certainly those erected by Iamani.

The fate of Ashdod-Yam was always connected to the important ancient city of Ashdod (Tel Ashdod), located about 5 km inland, which was one of the five major Philistine cities during the Iron Age (Fig. 1). In Late Antiquity, however, as is evident from the 6th-century Madaba mosaic map and historical sources, the coastal city of Azotos Paralios became more important than Inland Azotos (Azotos Mesogaios, known also as Hippenos; Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green 1994: 72). It seems that this shift in the region’s centre of gravity from Ashdod to Ashdod Yam can be detected much earlier, perhaps already during the Iron Age (Fantalkin 2014). The historical sources and archaeological evidence discovered so far suggest that during all periods of its existence Ashdod-Yam’s raison d’être was affiliated with the sea, being an integral part of an extensive Mediterranean coastal network.

During the Late Antiquity, which represents the peak of ancient settlement activity at Ashdod-Yam (Bäbler and Fantalkin 2023), the site was quite impressive, covering an area of at least 2 km from north to south, and ca. 1.5 km from east to west, as is evident from the aerial photograph taken in 1944 (Fig. 2).

Ashdod is mentioned several times in Assyrian and biblical accounts of the 8th–5thcenturies BCE (Dothan and Freedman 1967: 8–11). By the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, references to Ashdod (Azotos in Greek; Azotus in Latin) are more prevalent, especially in the Books of the Maccabees and the works of Josephus (ibid.: 11–13).However, the shift in regional prominence from Ashdod to Ashdod-Yam casts ambiguity over whether contemporary mentions of ‘Ashdod/Azotos’ refer to the inland or coastal site.

Azotos appears in the historical records relating to the Battle of Gaza in 312 BCE as the place to where Demetrius I of Macedon retreated following his defeat (Diod. 19.85).Subsequent mentions relate to the Hasmonaean period. Thus, Judas Maccabaeus raided but did not capture Azotos (1 Macc 4:15), although in a later campaign, ‘Judas marched toAzotus, the land of the aliens, destroyed their altars, burnt the images of their gods, carried off the spoil from their towns and returned to Judaea’ (1 Macc 5:68). Judas’ successor, Jonathan, defeated Apollonius, the general of Demetrius I, in the plains of Azotos, where he ‘burned down the city and the villages in the vicinity and plundered them’, destroying in the process the famous Temple of Dagon (1 Macc 10:83–84; cf. 1 Macc 11:4; Josephus,AJ 13.99–100).1 Later in the Hasmonaean period, Simon is reported to have settled Jews in Azotos (1 Macc 14:34) and John Hyrcanus I, following a successful battle against Cendebaeus (a general of Antiochus VII Sidetes in command of the coast of Palestine[1 Macc 15:38]), set fire to the towers in the fields of Azotos (1 Macc 16:10). Under Alexander Jannaeus, the city was under Jewish control (Josephus, AJ 13.395). It is listed as one of the cities Pompey detached from Jewish territory and restored to its original inhabitants (Josephus, AJ 14.75; BJ 1.156). At Tel Ashdod (the inland city), substantial Hellenistic remains were discovered mainly in Area A, featuring buildings of a new city plan oriented along a north–south axis (identified as local Strata 4–3, with Stratum 3 further divided into Phases 3a and 3b).Several groups of buildings divided by streets were interpreted as remains of the city’s agora (Dothan and Freedman 1967: 17–21). The end of Phase 3b was dated to the late 2ndcentury BCE, linking it to the Hasmonaean conquests of Azotos. This conclusion is based on a destruction layer at the site, which produced the latest coin dated to Antiochus VIII(114 BCE), thus providing a terminus post quem for the conquest of the city by John Hyrcanus I. Phase 3a, therefore, relates to the Hasmonaean occupation (ibid.: 27; Dothan1993: 102). The Hellenistic-period chronology for inland Azotos offers important contextual information, serving as a directly comparable benchmark for understanding the timeline of the coastal site at Ashdod-Yam.

1 For reconstruction of this battle, see, most recently, Safrai 2022.

Ashdod-Yam (Ashdod by the Sea) is located on the coast of Israel, ca. 5 km northwest of Tel Ashdod, which served as the main settlement in the region from the Bronze Age until the late Iron Age (Dothan, 1971; Dothan & Freedman, 1967; Dothan & Porath, 1982, 1993) (Figure 1). The fate of Ashdod-Yam was always connected to the capital city of Ashdod, although the region's center of gravity shifted from Ashdod to Ashdod-Yam in the classical periods and, perhaps, already during Iron Age IIB–C (Fantalkin, 2014).

Ashdod-Yam is a large site, spanning at least 2 km from north to south and ca. 1.5 km from east to west. It consists of several clearly definable areas, representing different periods of its history. A unique feature of the site is a large human-made enclosure at its southern end, which contains a massive fortification system and an associated acropolis, dating to Iron IIB–C (Figure 2). Additionally, a small site dating to the Late Bronze Age was uncovered ca. 1 km to the south of the enclosure (Nahshoni, 2013).

The Iron Age fortifications were partially excavated by Kaplan (1969). Ten cross-sections were dug along the edges of the rampart and glacis and exposed segments of the city wall. The fortification system consists of a 3.5–4.5 cm thick mudbrick wall, which served as a core for a large earthen rampart and an outer glacis laid on both sides (Kaplan, 1969, pp. 141–143). According to Kaplan, an additional segment of the wall, which would have fully enclosed the compound, stood at the western edge of the mound and was destroyed by erosion (Kaplan, 1953, p. 32, 1969, p. 138). Since Iron Age pottery was found during a survey of the site, beyond the ramparts, it is suspected that the fortified enclosure was part of a larger settlement, which may be buried under the accumulation of deposits and anthropic levels from the classical periods. The pottery retrieved from the rampart, outer glacis, and nearby locations was dated to Iron IIB (Kaplan, 1969, pp. 144–147).

Renewed excavations at the Iron Age compound of Ashdod-Yam were initiated in 2013 under the directorship of A. Fantalkin on behalf of the Institute of Archeology at Tel Aviv University. Four excavation seasons uncovered three main phases of occupation, which date to Iron IIB (Area B), Iron IIC (Areas C and D), and the Hellenistic period (Areas A, A1, and D) (Ashkenazi & Fantalkin, 2019; Fantalkin, 2014, 2018; Fantalkin et al., 2016) (Figure 2). According to Fantalkin's investigation, the fortification system was designed from the beginning in a crescent-shaped defensive form that extended over an area of more than 15 acres and featured a wide opening to the sea (contra Kaplan, 1969). Thus, the entire enclosure was constructed during the Iron IIB to protect a human-made harbor at Ashdod-Yam.

The construction of the site's Iron Age enclosure and its relation to the settlement at Tel Ashdod have been the subject of much debate over the past two decades (see summaries in Fantalkin [2001, 2014, 2018] and Itkin [2022]). While Kaplan (1969) argued that the enclosure was built on a local initiative as a response to a Neo-Assyrian threat, others interpret it as a Neo- Assyrian imperial enterprise (Finkelstein & Singer-Avitz, 2001; Na'aman, 2001). The question of the site's builders is essential to our understanding of the relations between the governing bodies and the craftsmen as well as the mechanisms that influenced craftsmanship at Ashdod-Yam. Thus, one of the major aims of the renewed excavations at the site is to understand the agency behind the establishment of Ashdod-Yam, be it on behalf of the Neo-Assyrian ruling regime or on behalf of the kingdom of Ashdod, which was later incorporated into the Assyrian realm.

In what follows, the architectural remains associated with the Iron Age sequence at Ashdod-Yam are discussed. These primarily include the fortification wall (Wall 2002, Area B) and a large public structure (Building 5175, Area D) uncovered on the acropolis (Figure 3). Additionally, the Hellenistic remains at the site are also mentioned (Areas A, A1, and D) for comparative purposes.

Nowadays, the remaining archaeological site is surrounded by modern buildings and enjoys the status of a protected zone (Fig. 3). In the southern part of the site there is a mound (acropolis) incorporated into an artificial enclosure, constructed and occupied during the Iron Age IIB-IIC (8th-7th centuries BCE) and the Hellenistic Period (Kaplan 1969; Fantalkin 2014; Id. 2018; Fantalkin, Johananoff and Krispin 2016; Ashkenazi and Fantalkin 2019). The remains of the Roman-Byzantine city, covered by dunes, are spread to the north of the enclosure. Except for a few cemeteries (Pipano 1990; Ganor 2017), until recently archaeological excavations have revealed little about the city during these periods. An impressive citadel (40 × 60 m), which has been identified as the ribat mentioned by al-Muqaddasi (10th century CE), dating from the Early Islamic period, is located in the northern part of the site. During the excavation of the fortress by the Israel Antiquities Authority, traces of four large rectangular complexes, interpreted as remains of the late antique insulae, were discovered directly beneath the Islamic structure (Nachlieli 2008; Raphael 2014). Following strong winter storms that occurred during the last decades, quite a number of harbour storage facilities of the Byzantine period were exposed to the north and to the south of the Islamic fortress.

Starting in 2013, a new excavation project on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University was launched at the site of Ashdod-Yam, under the direction of Alexander Fantalkin.

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

General location map

(created by Itamar Ben-Ezra)

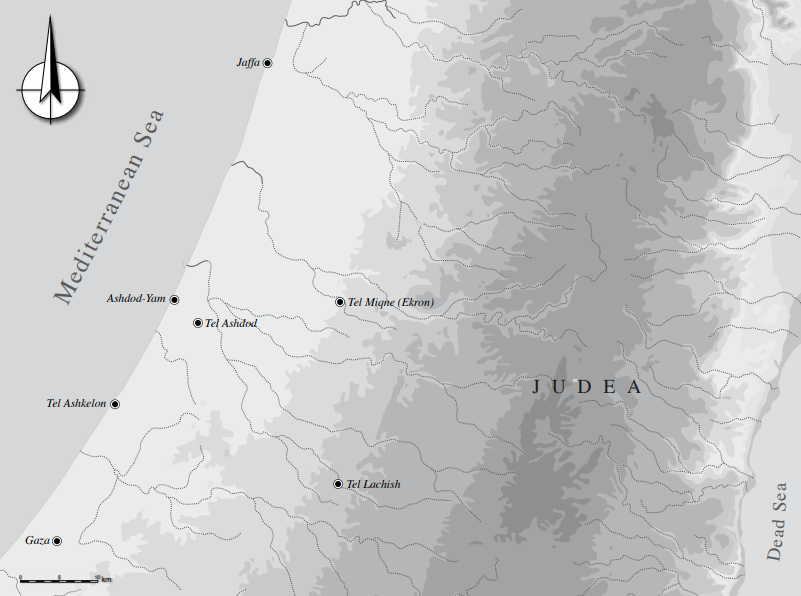

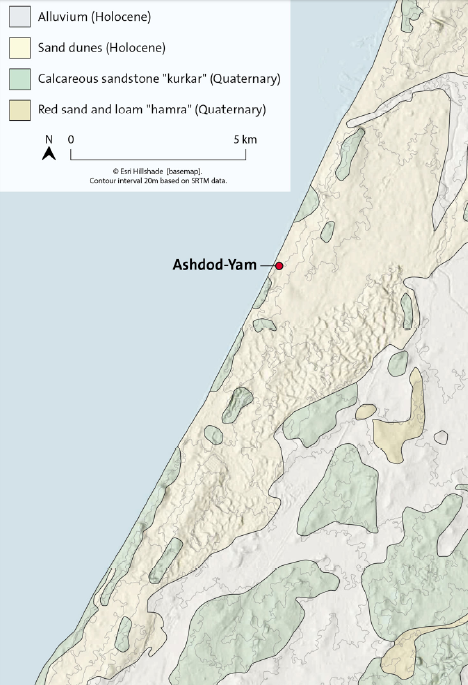

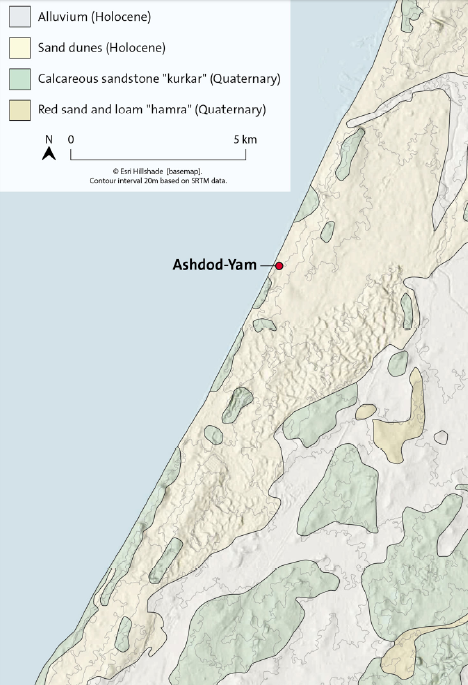

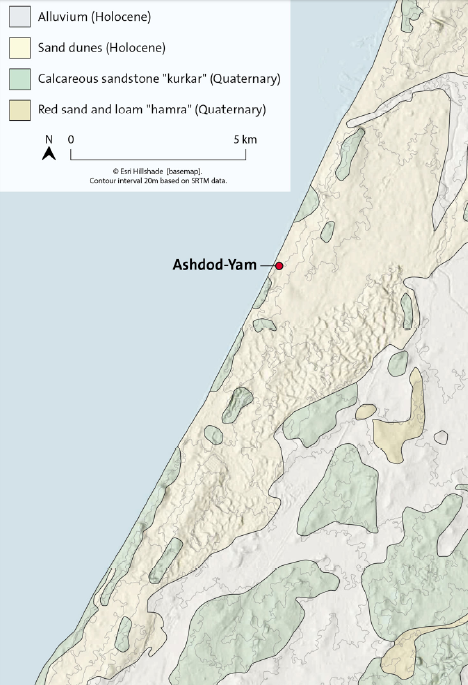

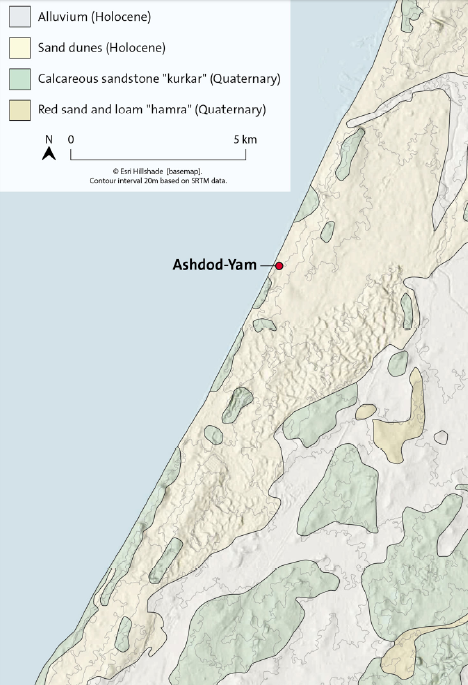

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 7 - Geologic Map

of the area from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Geological map of the area

(drawing by Maija Holappa after Sneh and Rosensaft [2004])

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

- Fig. 7 - Geologic Map

of the area from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Geological map of the area

(drawing by Maija Holappa after Sneh and Rosensaft [2004])

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

- Annotated Satellite Image (google) of

the Ashdod-Yam from biblewalks.com

- Fig. 3 - Modern Aerial photograph

of Ashdod-Yam from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Modern aerial photograph of Ashdod-Yam. The location of the excavated basilica is marked with a white dot

(created by Yaniv Darvasi)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 2 - Aerial photograph

of Ashdod-Yam from 1944 from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial photograph of Ashdod-Yam taken in 1944

(courtesy of the Survey of Israel)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 2 Annotated Aerial

photograph of Ashdod-Yam from 1944 from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial photograph of Ashdod-Yam taken in 1944, including key landmarks.

(Courtesy of the Survey of Israel.)

Fantalkin et al. (2024) - Fig. 9 LIDAR image of

Ashdod-Yam showing key landmarks from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

LIDAR image of Ashdod-Yam showing key landmarks. Kaplan’s excavation trenches are visible along the perimeter of the fortifications

(Created by SEE Advanced Mapping Systems and Solutions Ltd.; courtesy of the authors.)

Fantalkin et al. (2024) - Ashdod-Yam in Google Earth

- Ashdod-Yam on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Annotated Aerial view

of the acropolis from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of the acropolis (looking south) in 2013, showing the excavated areas

(photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; modified by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 6 - Oblique aerial photo of Byzantine

Church Complex showing 3 phases from Fantalkin (2023)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Church complex (looking West), with its three suggested constructional phases:

- Stage 1 (blue)

- Stage 2 (red)

- Stage 3 (green)

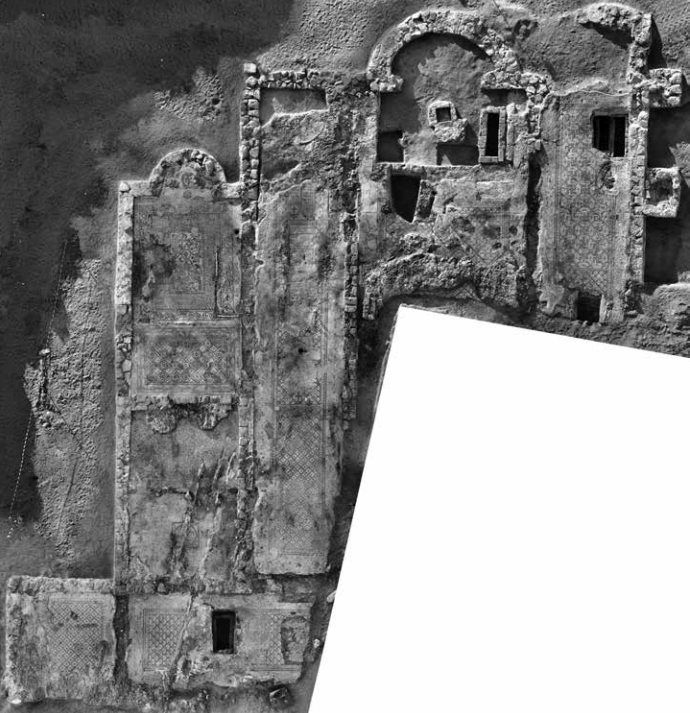

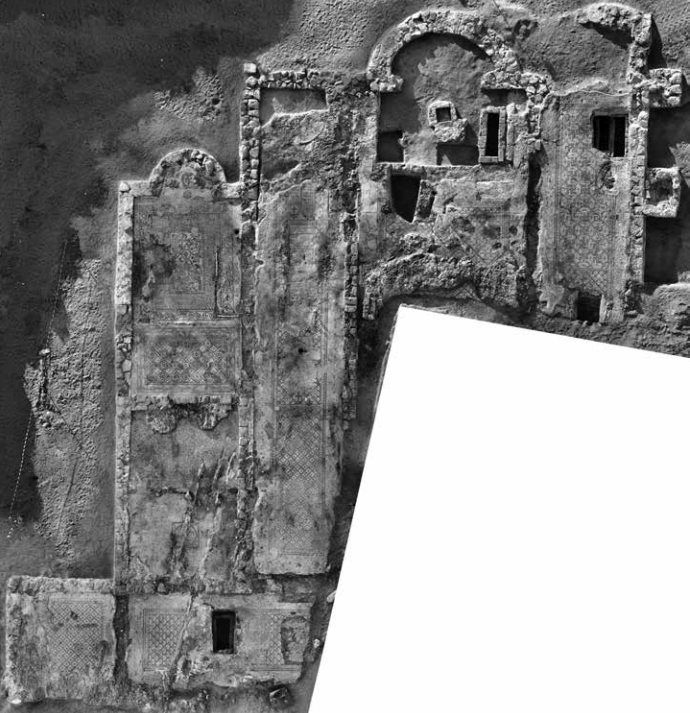

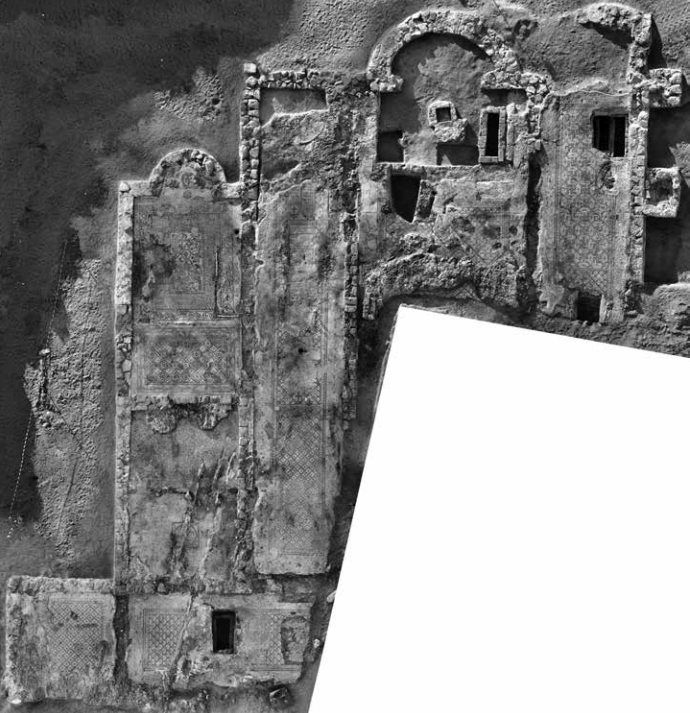

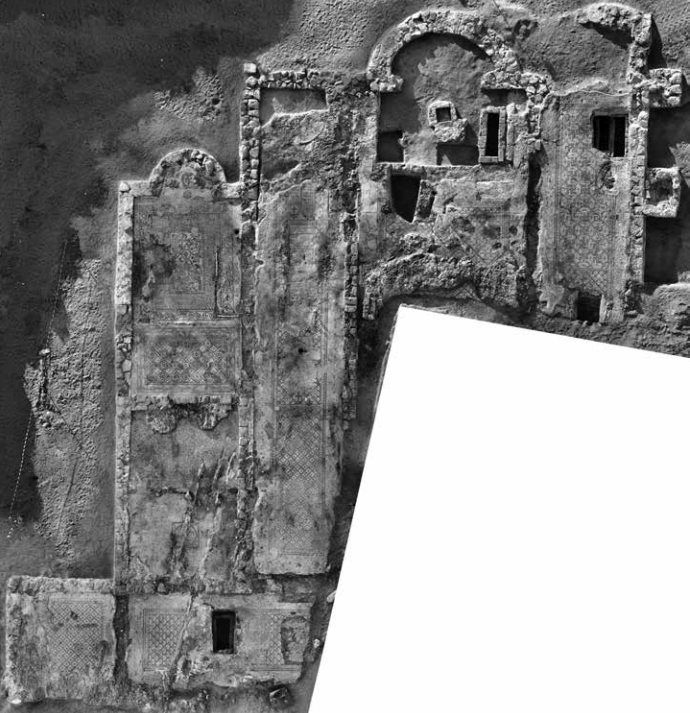

Fantalkin (2023) - Fig. 6 - Orthophoto of excavated Byzantine

Church Complex from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

The orthophoto of the excavated complex

(created by Slava Pirsky and Sergey Alon)

Di Segni et al. (2022)

- Fig. 2 - Aerial View of areas A, B, and D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

View to the south showing the excavation areas at Ashdod-Yam

- Area A in which the Hellenistic structures were found

- Area B includes part of the fortification wall

- Area D encompasses the acropolis

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography.)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 11 Aerial photograph

of the acropolis showing Areas A, A1, B, C, and D from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Aerial photograph of the acropolis (looking south) from 2013 showing current excavation areas.

(Photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; courtesy of the authors.)

Fantalkin et al. (2024)

- Fig. 3 General Plan of

the Ashdod-Yam site from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General plan of the Ashdod-Yam site showing the number and location of Kaplan’s excavation trenches (or cross-sections)

(Modified by S. Pirsky, after Kaplan 1969: fig. 2; courtesy of the authors)

Fantalkin et al. (2024)

- Fig. 3 General Plan of

the Ashdod-Yam site from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General plan of the Ashdod-Yam site showing the number and location of Kaplan’s excavation trenches (or cross-sections)

(Modified by S. Pirsky, after Kaplan 1969: fig. 2; courtesy of the authors)

Fantalkin et al. (2024)

- Plan of Citadel and

excavation areas of Ashdod-Yam from Stern et. al. (2008)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Citadel and

excavation areas of Ashdod-Yam from Stern et. al. (2008)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Stern et. al. (2008)

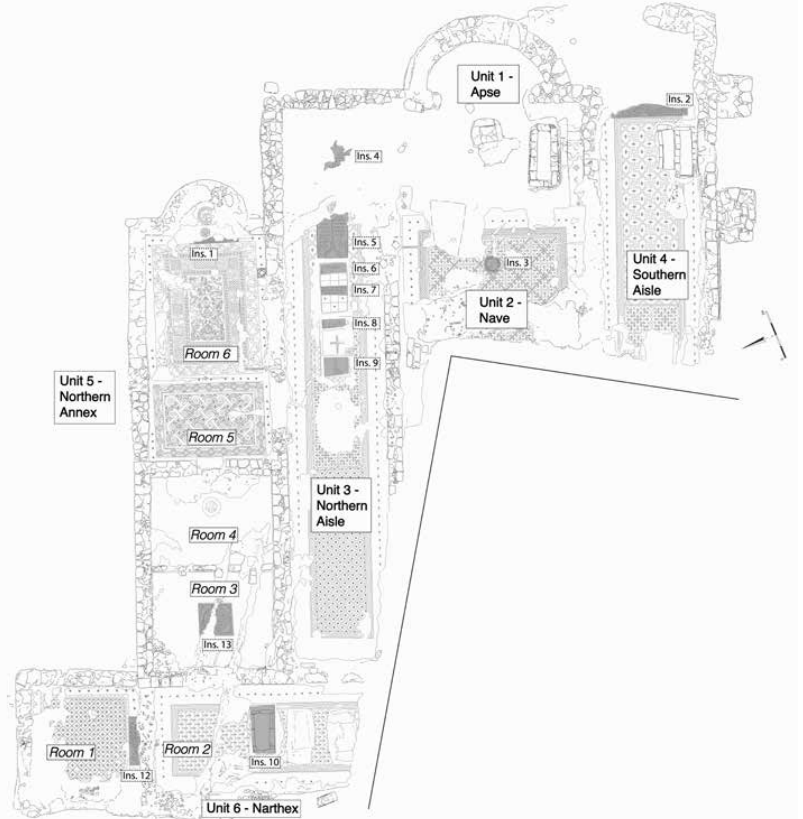

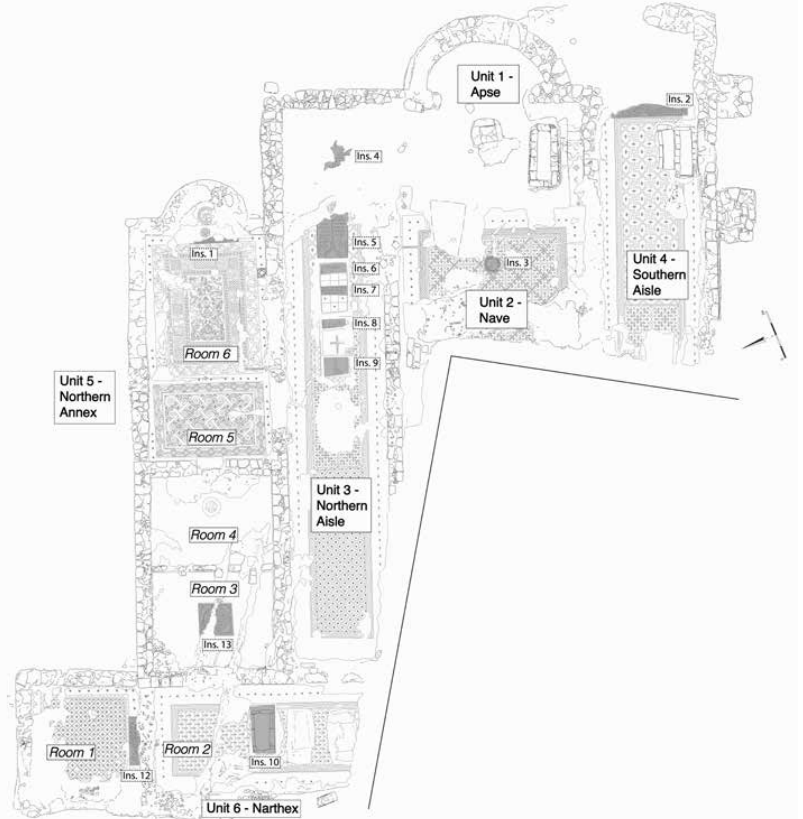

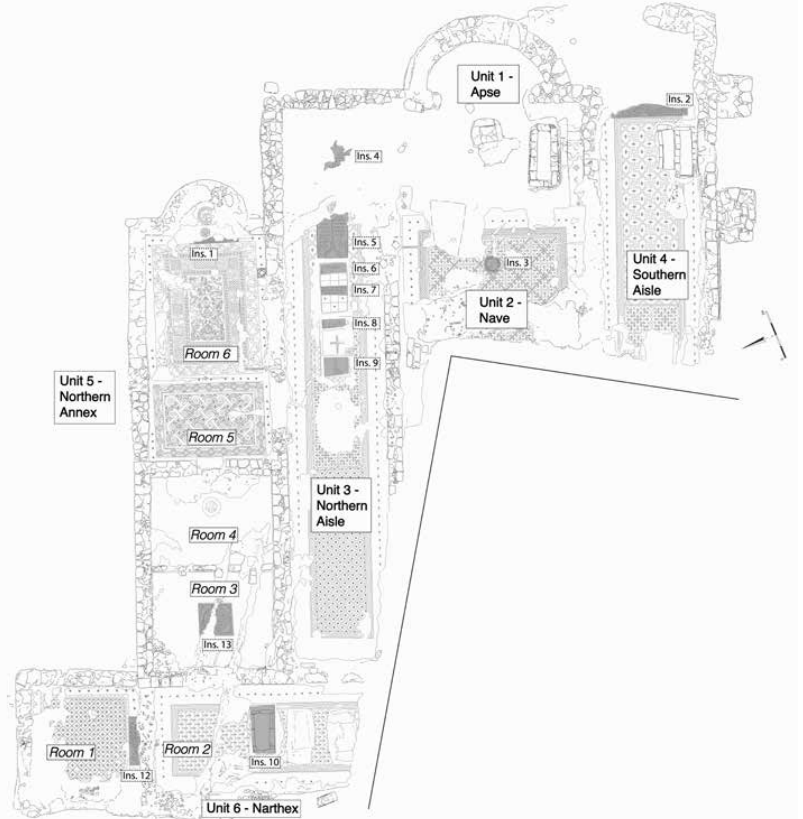

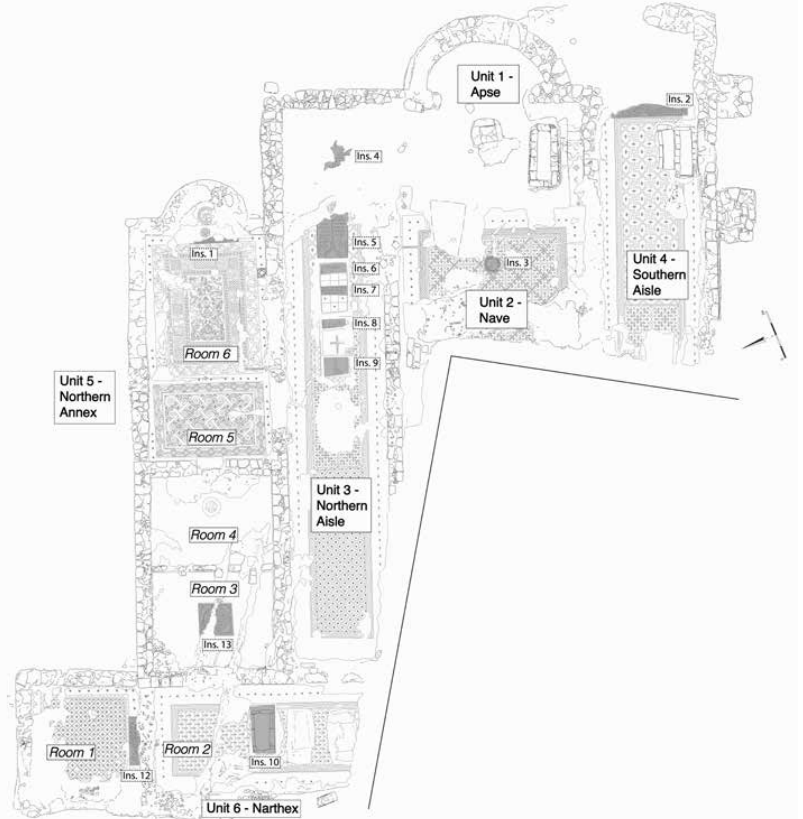

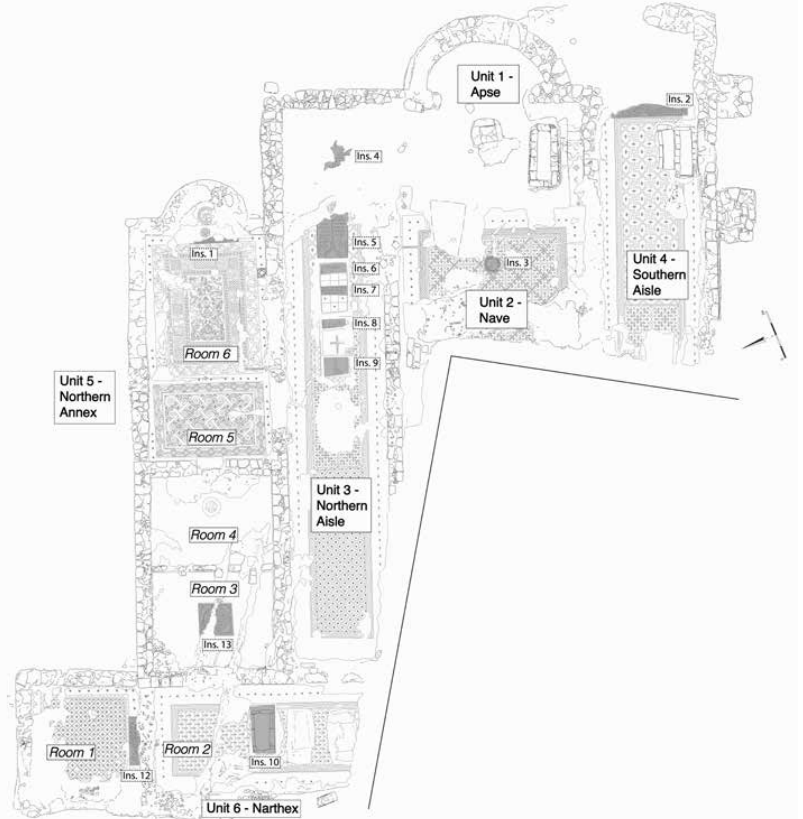

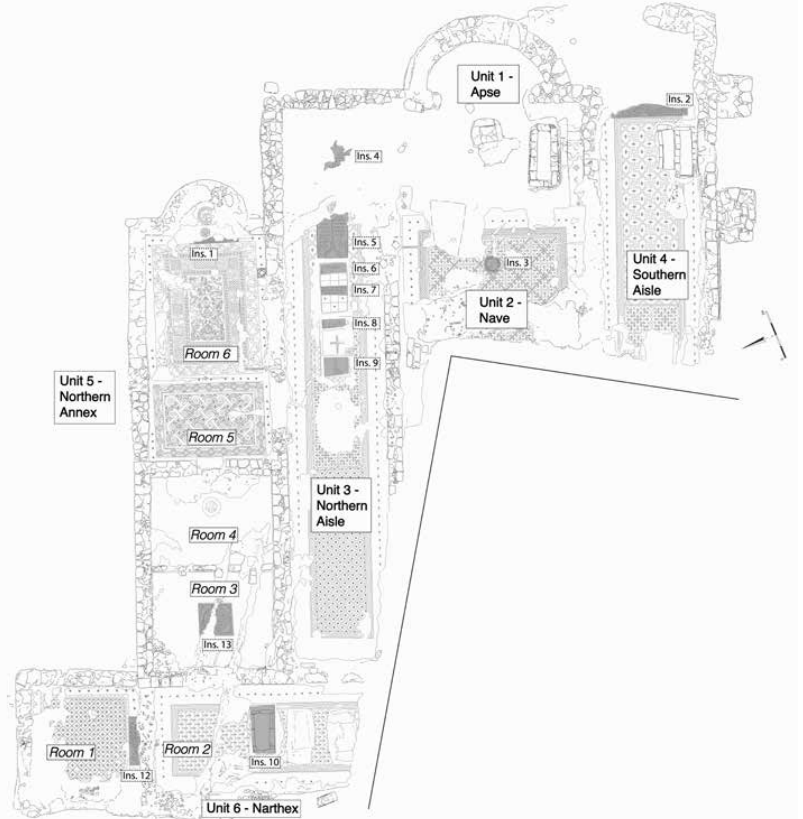

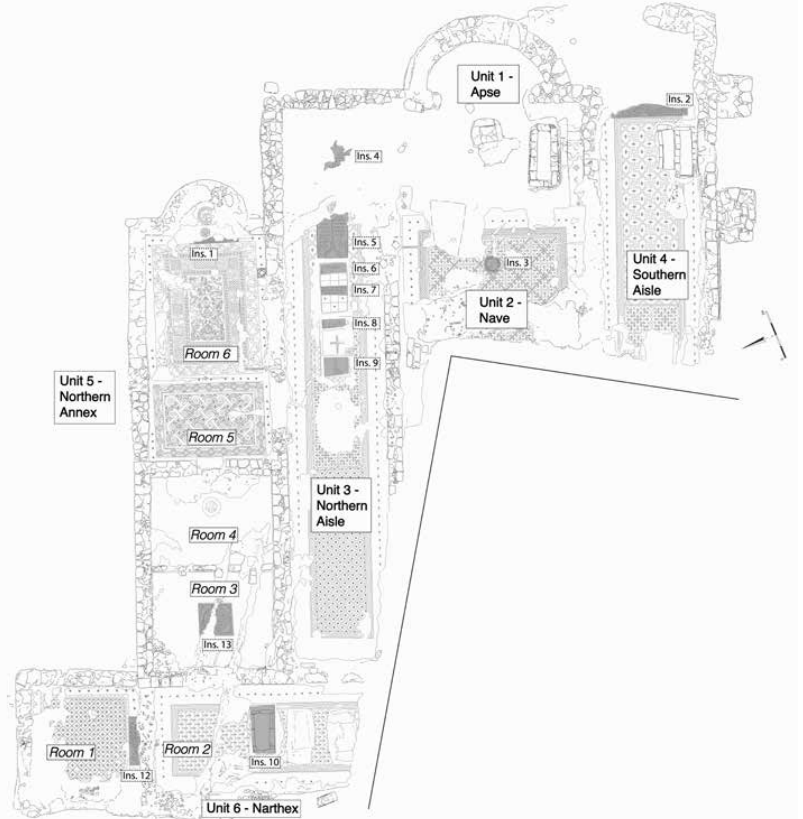

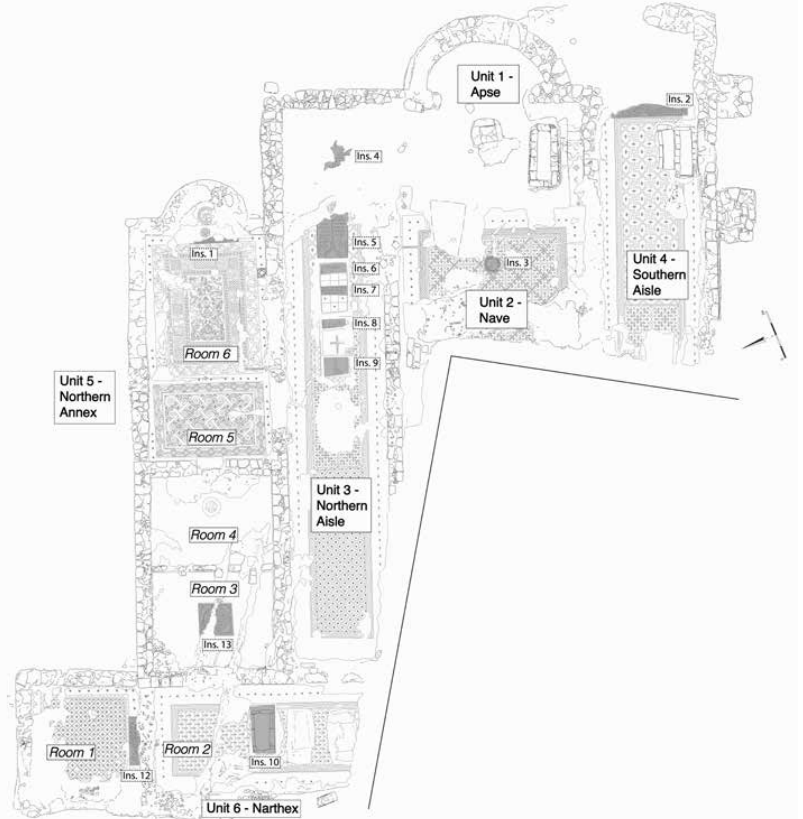

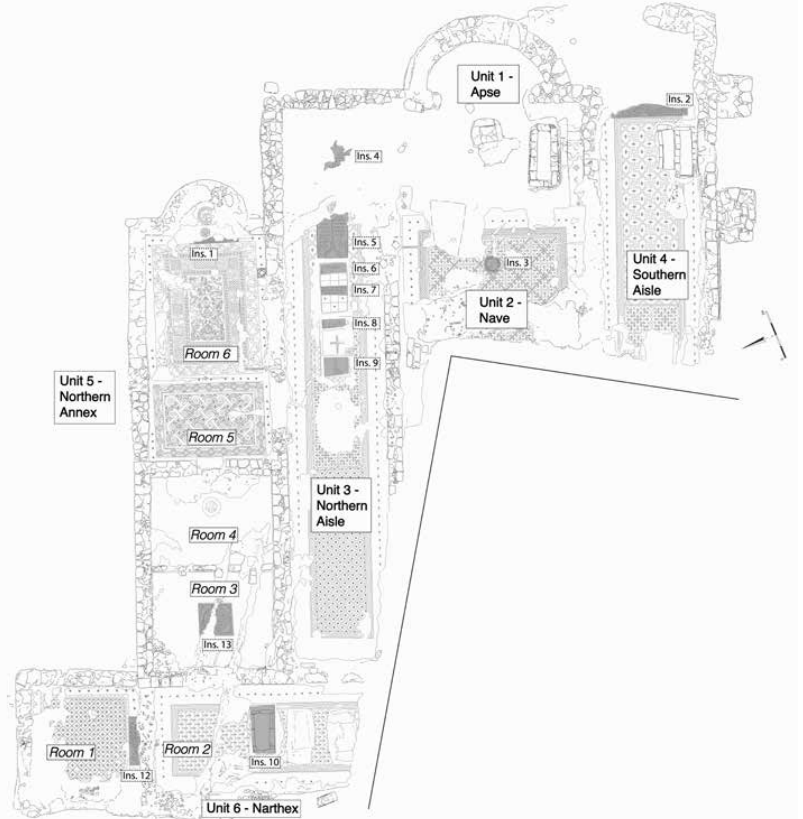

- Fig. 5 - Plan of excavated

Byzantine Church Complex from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of the excavated complex and location of the inscriptions

(created by Slava Pirsky and Liora Bouzaglou)

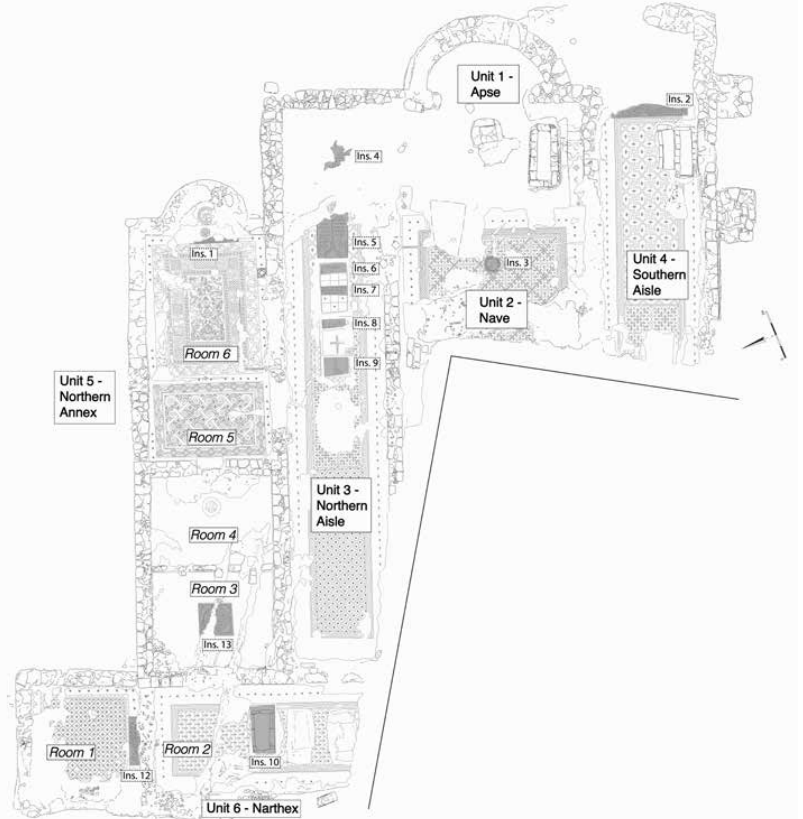

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 15 Final stratigraphic

and architectural phases of the Byzantine Church Complex from Darvasi et al. (2024)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Final stratigraphic and architectural phases of the excavated complex

(created by Slava Pirsky, Liora Bouzaglou, & Alexander Fantalkin)

Darvasi et al. (2024) - Fig. 14 Orthophoto

of the Byzantine Church Complex from Darvasi et al. (2024)

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Orthophoto at July/August 2021 season end

(created by Slava Pirsky and Sergey Alon)

Darvasi et al. (2024)

- Fig. 5 - Plan of excavated

Byzantine Church Complex from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of the excavated complex and location of the inscriptions

(created by Slava Pirsky and Liora Bouzaglou)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 15 Final stratigraphic

and architectural phases of the Byzantine Church Complex from Darvasi et al. (2024)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Final stratigraphic and architectural phases of the excavated complex

(created by Slava Pirsky, Liora Bouzaglou, & Alexander Fantalkin)

Darvasi et al. (2024) - Fig. 14 Orthophoto

of the Byzantine Church Complex from Darvasi et al. (2024)

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Orthophoto at July/August 2021 season end

(created by Slava Pirsky and Sergey Alon)

Darvasi et al. (2024)

- Fig. 2 Annotated Aerial view

of the acropolis from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of the acropolis (looking south) in 2013, showing the excavated areas

(photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; modified by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of excavation areas in Ashdod Yam

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 12 Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Map of current excavation areas

(Drawing by S. Pirsky; courtesy of the authors)

Fantalkin et al. (2024)

- Fig. 2 Annotated Aerial view

of the acropolis from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of the acropolis (looking south) in 2013, showing the excavated areas

(photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; modified by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of excavation areas in Ashdod Yam

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 12 Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Fantalkin et al. (2024)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Map of current excavation areas

(Drawing by S. Pirsky; courtesy of the authors)

Fantalkin et al. (2024)

- Fig. 5 - Plan of Area D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of Area D with Iron Age and Hellenistic remains

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy and Eli Itkin)

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

- Fig. 5 - Plan of Area D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of Area D with Iron Age and Hellenistic remains

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy and Eli Itkin)

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

- Fig. 4 Plan of Area A

from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of Area A

(drawing by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b) - Fig. 5 Unit 1 in Area A

featuring evidence of the mudbrick wall collapse from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Unit 1 in Area A, featuring evidence of the mudbrick wall collapse

(drawing by S. Pirsky; photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 4 Plan of Area A

from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of Area A

(drawing by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b) - Fig. 5 Unit 1 in Area A

featuring evidence of the mudbrick wall collapse from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Unit 1 in Area A, featuring evidence of the mudbrick wall collapse

(drawing by S. Pirsky; photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 28 Reconstruction

of the Stratum II settlement from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Reconstruction of the Stratum II settlement

(drawing by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 28 Reconstruction

of the Stratum II settlement from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Reconstruction of the Stratum II settlement

(drawing by S. Pirsky)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 21 - Destruction

debris in the Byzantine Chapel from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

The destruction debris during the excavations of the chapel in Unit 5

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 22 - Destruction

debris in the Byzantine nave from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

The destruction debris during the excavations of the nave in Unit 2

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Collapsed

Hellenistic mudbricks in Area A from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 Unit 1 in Area A

Wall W.117 built of mudbrick directly on sand from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Unit 1 in Area A: W.117, built of mudbricks directly on sand, looking northeast

(photo by P. Shrago)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 21 - Destruction

debris in the Byzantine Chapel from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

The destruction debris during the excavations of the chapel in Unit 5

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 22 - Destruction

debris in the Byzantine nave from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

The destruction debris during the excavations of the nave in Unit 2

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Collapsed

Hellenistic mudbricks in Area A from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 Unit 1 in Area A

Wall W.117 built of mudbrick directly on sand from Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Unit 1 in Area A: W.117, built of mudbricks directly on sand, looking northeast

(photo by P. Shrago)

Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

- from Fantalkin (2023)

| Phase | Dates (CE) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | early 5th century | (the main church): Based on the date of the earliest inscription (441/442 CE), located at the easternmost side of the northern aisle, the church was constructed in the early fifth century CE. This prominent inscription, dedicated to one of the deaconesses, is also the first and the longest in a whole row of dedicatory inscriptions located in the northern aisle. |

| 2 | middle of 5th century | Based on the dates of the inscriptions, the elaborate chapel has been attached to the eastern part of the northern aisle from the

north around the middle of the fifth century CE. It is covered by a mosaic that is framed with ivy leaves in red and black, and a complex

geometrical pattern. The central picture consists of an "inhabited

scroll" with wine leaves emanating from a cantharos at the bottom,

flanked by antithetical peacocks and nine medallions. These medallions depict, at the center, a bird in a cage, flanked by a lion and a deer.

Above the cage, one finds a fruit bowl, flanked by birds. At the top,

one can see a predatory cat attacking what is probably a calf (fig. 7).52

In the outer margin of the mosaic floor a clay jug was inserted into the

floor, filled with an oily mixture of sand. The jug was carefully closed

with a tile. At a certain stage, a small apse was added to the eastern

side of the chapel. The floor of the apse is decorated with mosaics featuring a rose of Jericho in red and black, a medallion with a cross, and

the monogram Alpha and Omega.

Footnotes

52 The mosaics have been studied and are being prepared for publication by Lihi Habas (Hebrew University of Jerusalem). |

| 3 | 6th century | Based on the dates of the inscriptions, one may assume that during the course of the sixth century CE a series of rooms were added to the west of the chapel from Stage 2, abutting the northern aisle of the church as well. The floors of these rooms, the functions of which remain to be clarified, were covered with the spiralled carpet mosaics. |

| Stratum | Period | Dates (BCE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Iron Age IIB | ||

| III | Iron Age IIC |

|

Area A is at the northern edge of the Ashdod-Yam acropolis. It features major architectural remains dating to the Hellenistic period, comprising three separate structural units with a northwest to southeast orientation (Fig. 4). Based on the relatively modest amounts of pottery and coins found among these structures, it seems that the buildings were abandoned sometime in the late 2nd century BCE before their subsequent collapse—possibly (as detailed in the discussion) from a major earthquake.

| Unit | Period | Dates (BCE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The remains of a mudbrick wall were exposed along with the adjoining remains of an impressive collapse (Fig. 5). The wall was established directly on sand with no foundation (Fig. 6) and was preserved to a height of five courses with the sun-dried mudbricks laid in a running bond technique. No adjoining floors were detected in this unit, except for a patchy clay surface abutting the southern part of the wall from the west. The bricks measured approximately 39×39×10 cm. In general, the matrix of the Hellenistic mudbricks presents a similar geochemical pattern to earlier Iron Age mudbricks used at the site; however, an additional stage was detected in the Hellenistic production—the inclusion of crushed seashells and crushed pottery (Lorenzon et al. 2023). Finds recovered among the eroded bricks included three coins of Antiochus IV, all from a mint of Ptolemais ('Akko), ca. 173/2–168 BCE, and a single coin from the reign of Antiochus III (see below, Coins). | ||

| 2 | The partially preserved remains of a building were discovered here (Fig. 7). Two major intersecting walls divided the area into four rooms. The collapsed walls were of sun-dried mudbricks, similar in dimensions to those uncovered in Unit 1, but laid on foundations of local beachrock (1 m wide; 0.5 m high), the trenches for which had been dug in the sand. Some of the foundation stones had been robbed, accessed by a robber’s trench. The collapsed mudbricks from the upper parts of the walls covered traces of poorly preserved occupation surfaces made of beaten earth. In Room A, mudbrick detritus covered such a deteriorated surface (L.141). In Room B, the poorly preserved surface (L.168) was covered by collapsed mudbrick debris, related to the collapse of the upper mudbrick courses of W.171. A coin of Ptolemy II, from Alexandria, ca. 266–261 BCE, was recovered from the eroded bricks. To the west of the collapse was a horseshoe-shaped clay tabun (I.108). The surviving part of Room C was covered by a mudbrick collapse (L.116) related to the robbed foundation of W.107 to its northwest. This collapse was partially excavated, revealing a poorly preserved occupation surface without finds. | ||

| 3 | The remains of a poorly preserved structure with lower foundations of beachrock were discovered here (Fig. 8). Two coins of Antiochus IV, both from a mint of Ptolemais ('Akko), ca. 173/2–168 BCE, were found in the eroded brick of this structure. A deep probe undertaken in the southeastern corner (Square PA29) revealed that beneath the Hellenistic structure, there was a very thick layer of sterile sand (L.120; Fig. 9). This suggests that the Hellenistic occupation was established long after the destruction and abandonment of the Iron Age settlement. About 15 m west of Unit 3 (Square KA30), a refuse pit filled with stones, Hellenistic pottery sherds and four phallic-shaped lead weights was uncovered (see below, Metals and Fig. 25:9). |

Area A1, near the northwestern edge of the acropolis, features the foundations of a wall (W.248) of a substantial building oriented north–south (ca. 26×1.6 m) (Fig. 10). It appears to be the outer western wall of a monumental structure, almost certainly a fortress, that would have dominated the highest spot on the acropolis. The upper courses of the exposed wall had been robbed in antiquity; however, the lower courses of large ashlar stones were partially preserved in several places. The remains included three monumental pillars made of colossal ashlar blocks, incorporated into the wall.

The northern pillar (I.207) was located at the northern end of Wall 248 (Fig. 11). It had several surviving courses, comprising semi-dressed beach-rock followed by large, dressed kurkar (a calcareous sandstone) and, topping these lower courses, a finely dressed limestone monolith measuring 1.5×1.2×1.4 m—i.e., 2.52 m3. On the assumption that the density of limestone is 2,711 kg/m3 at standard atmospheric pressure, the estimated weight of the monolith would be around 6,832 kg. Traces of plaster found on the northern pillar suggest that it had originally been plastered. A plaster floor with embedded crushed shells (L.246), found abutting the northern pillar, is probably an occupation surface connected to the main building from the outside (Fig. 12). An ashy destruction layer mixed with mudbrick debris was exposed on top of this surface. An additional plaster floor with embedded crushed shells and kurkar (F.247) was detected northwest of the northern pillar, abutting the foundations of a small partition wall (W.261). Two courses of Wall 261 were preserved, abutting the northern pillar from the west (Fig. 13).

The remains of a middle pillar (I.257) were found about 14.4 m south of the northern pillar along the line of Wall 248 (Fig. 14). The middle pillar comprised a monolith of dressed limestone, measuring 1×1.2×1 m—i.e., 1.2 m3, with an estimated weight of around 3,253 kg. Traces of plaster were also observed on this pillar. The preserved height of its monolith top is considerably lower than that of the northern and southern pillars (see below); this means that an additional monolith would have been required to bring the middle pillar up to the same level. Abutting the base of the middle pillar from the north were two remaining foundation courses of W.248, comprising a row of well-dressed kurkar stones, arranged as headers. From the south side of the middle pillar, the dismantled debris of W.248 could also be observed, providing a physical connection between this pillar and the next.

The southern pillar (I.258), 6.7 m south of the middle pillar along the line of W.248, comprised three lower courses of dressed kurkar and an upper course of a large limestone monolith, 1.2×1.8×1.3 (Fig. 14)—i.e., 2.808 m3, with an estimated weight of around 7,612 kg. An upper part of what appears to be an additional monolith was discovered east of and adjacent to the southern pillar’s monolith. This structure may have been part of a wall approaching the southern pillar from the east. North of the southern pillar, the two remaining courses of the foundations of W.248 were of well-dressed kurkar stones, partially arranged as headers and stretchers. Some featured marginal signs of dressing (Fig. 15) and clearly belonged to spolia from an earlier Hellenistic building, located elsewhere. Considering the distance and physical connection between the surviving middle pillar and the northern pillar, one may assume that an additional pillar would have been required between them. The missing pillar (estimated to have been near Square FA30; see Fig. 10) was likely robbed in antiquity.

As a result of stone robbery, as well as seasonal rainfalls and landslides, earlier Hellenistic surfaces that originally abutted Wall 248 of the monumental building eroded and collapsed into the stone-robbers’ trench, where they were ultimately buried by sand (Fig. 16). Accumulations of eroded material from the floors were visible at the bottom of the trench and along its section. One of these, from a floor of the monumental building, yielded an especially rich assemblage in terms of restorable Hellenistic pottery and accompanying metal finds (L.252). Judging from the thick ash deposits on the floors, the charred organic materials and the variety of small finds and restorable vessels, the entire structure was destroyed by fire in the late 2nd century BCE.

Area D East features a single architectural unit—Building 5174—and a round installation (L.5066) (Fig. 17). Building 5174 is a rectangular structure (8×8.5 m), divided into three spaces, with mudbrick walls built on partially hewn beachrock stones. The northern wall consisted of five courses (ca. 7.7×0.9 m), which were cut into the Stratum III (Iron IIC) remains. The eastern and southern parts of the structure were poorly preserved and lacked evidence of a floor. Better preservation was attested in the southwestern corner (Square EA20), where a compacted, crushed, kurkar floor was uncovered. The accumulation above this floor contained Hellenistic pottery and several pieces of plaster. Below it, an additional patch of collapsed wall plaster appears to have sealed the occupational accumulation above an earlier floor containing several restorable vessels.

No evidence of a conflagration or deliberate destruction was found in Building 5174. This, combined with the limited ceramic assemblage, suggests that the building was probably deserted. However, the northern bounding wall of the structure is noticeably tilted southward and the entire building is tilted westward (Fig. 18). Coupled with the bad state of preservation, this phenomenon may be the result of a natural event — perhaps the earthquake postulated from the remains in Area A. The location and plan of the structure suggest that it served as a watchtower. Such an identification is supported by the impressive width and depth of its foundations, which must have supported a large superstructure (Fig. 19).

The circular, mudbrick-lined installation L.5066 is 37 cm deep and ca. 2 m in diameter, with a channel cut in its southern half. Like Building 5174, the installation penetrated earlier, Stratum III, remains. Although its function is unclear, it resembles a small silo or possibly a platform/foundation for a bread oven. Similar bread ovens, dating to the Hellenistic period, have been uncovered at Heliopolis and Tell Timai in Egypt (Hudson 2016: 210, Fig. 10). If this was indeed its intended function, the construction of this installation must have been left unfinished in antiquity, as there is no evidence of fire (e.g., ash or charcoal) in or around it.

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

Table 1

Table 1A chronological scheme for the Levant (after Finkelstein 2010 and 2011; Regev et al. 2012; Sharon 2013).

Palmisano et al. (2019)

- Fig. 2 - Aerial View of area A, B, and D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

View to the south showing the excavation areas at Ashdod-Yam

- Area A in which the Hellenistic structures were found

- Area B includes part of the fortification wall

- Area D encompasses the acropolis

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography.)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Plan of Citadel and excavation

areas of Ashdod-Yam from Stern et. al. (2008)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 3 - Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of excavation areas in Ashdod Yam

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 5 - Plan of Area D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of Area D with Iron Age and Hellenistic remains

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy and Eli Itkin)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Collapsed Hellenistic mudbricks

in Area A from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

- Plan of Citadel and excavation

areas of Ashdod-Yam from Stern et. al. (2008)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Ashdod-Yam: plan of the excavation (Citadel)

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 3 - Excavation Areas

A, A1, B, C, and D from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of excavation areas in Ashdod Yam

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 5 - Plan of Area D

from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of Area D with Iron Age and Hellenistic remains

(Credit: Slava Pirskiy and Eli Itkin)

Lorenzon et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Collapsed Hellenistic mudbricks

in Area A from Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall

(Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography)

Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Area A is at the northern edge of the Ashdod-Yam acropolis. It features major architectural remains dating to the Hellenistic period, comprising three separate structural units with a northwest to southeast orientation (Fig. 4). Based on the relatively modest amounts of pottery and coins found among these structures, it seems that the buildings were abandoned sometime in the late 2nd century BCE before their subsequent collapse—possibly (as detailed in the discussion) from a major earthquake.

| Unit | Period | Dates (BCE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The remains of a mudbrick wall were exposed along with the adjoining remains of an impressive collapse (Fig. 5). The wall was established directly on sand with no foundation (Fig. 6) and was preserved to a height of five courses with the sun-dried mudbricks laid in a running bond technique. No adjoining floors were detected in this unit, except for a patchy clay surface abutting the southern part of the wall from the west. The bricks measured approximately 39×39×10 cm. In general, the matrix of the Hellenistic mudbricks presents a similar geochemical pattern to earlier Iron Age mudbricks used at the site; however, an additional stage was detected in the Hellenistic production—the inclusion of crushed seashells and crushed pottery (Lorenzon et al. 2023). Finds recovered among the eroded bricks included three coins of Antiochus IV, all from a mint of Ptolemais ('Akko), ca. 173/2–168 BCE, and a single coin from the reign of Antiochus III (see below, Coins). | ||

| 2 | The partially preserved remains of a building were discovered here (Fig. 7). Two major intersecting walls divided the area into four rooms. The collapsed walls were of sun-dried mudbricks, similar in dimensions to those uncovered in Unit 1, but laid on foundations of local beachrock (1 m wide; 0.5 m high), the trenches for which had been dug in the sand. Some of the foundation stones had been robbed, accessed by a robber’s trench. The collapsed mudbricks from the upper parts of the walls covered traces of poorly preserved occupation surfaces made of beaten earth. In Room A, mudbrick detritus covered such a deteriorated surface (L.141). In Room B, the poorly preserved surface (L.168) was covered by collapsed mudbrick debris, related to the collapse of the upper mudbrick courses of W.171. A coin of Ptolemy II, from Alexandria, ca. 266–261 BCE, was recovered from the eroded bricks. To the west of the collapse was a horseshoe-shaped clay tabun (I.108). The surviving part of Room C was covered by a mudbrick collapse (L.116) related to the robbed foundation of W.107 to its northwest. This collapse was partially excavated, revealing a poorly preserved occupation surface without finds. | ||

| 3 | The remains of a poorly preserved structure with lower foundations of beachrock were discovered here (Fig. 8). Two coins of Antiochus IV, both from a mint of Ptolemais ('Akko), ca. 173/2–168 BCE, were found in the eroded brick of this structure. A deep probe undertaken in the southeastern corner (Square PA29) revealed that beneath the Hellenistic structure, there was a very thick layer of sterile sand (L.120; Fig. 9). This suggests that the Hellenistic occupation was established long after the destruction and abandonment of the Iron Age settlement. About 15 m west of Unit 3 (Square KA30), a refuse pit filled with stones, Hellenistic pottery sherds and four phallic-shaped lead weights was uncovered (see below, Metals and Fig. 25:9). |

Area A1, near the northwestern edge of the acropolis, features the foundations of a wall (W.248) of a substantial building oriented north–south (ca. 26×1.6 m) (Fig. 10). It appears to be the outer western wall of a monumental structure, almost certainly a fortress, that would have dominated the highest spot on the acropolis. The upper courses of the exposed wall had been robbed in antiquity; however, the lower courses of large ashlar stones were partially preserved in several places. The remains included three monumental pillars made of colossal ashlar blocks, incorporated into the wall.

The northern pillar (I.207) was located at the northern end of Wall 248 (Fig. 11). It had several surviving courses, comprising semi-dressed beach-rock followed by large, dressed kurkar (a calcareous sandstone) and, topping these lower courses, a finely dressed limestone monolith measuring 1.5×1.2×1.4 m—i.e., 2.52 m3. On the assumption that the density of limestone is 2,711 kg/m3 at standard atmospheric pressure, the estimated weight of the monolith would be around 6,832 kg. Traces of plaster found on the northern pillar suggest that it had originally been plastered. A plaster floor with embedded crushed shells (L.246), found abutting the northern pillar, is probably an occupation surface connected to the main building from the outside (Fig. 12). An ashy destruction layer mixed with mudbrick debris was exposed on top of this surface. An additional plaster floor with embedded crushed shells and kurkar (F.247) was detected northwest of the northern pillar, abutting the foundations of a small partition wall (W.261). Two courses of Wall 261 were preserved, abutting the northern pillar from the west (Fig. 13).

The remains of a middle pillar (I.257) were found about 14.4 m south of the northern pillar along the line of Wall 248 (Fig. 14). The middle pillar comprised a monolith of dressed limestone, measuring 1×1.2×1 m—i.e., 1.2 m3, with an estimated weight of around 3,253 kg. Traces of plaster were also observed on this pillar. The preserved height of its monolith top is considerably lower than that of the northern and southern pillars (see below); this means that an additional monolith would have been required to bring the middle pillar up to the same level. Abutting the base of the middle pillar from the north were two remaining foundation courses of W.248, comprising a row of well-dressed kurkar stones, arranged as headers. From the south side of the middle pillar, the dismantled debris of W.248 could also be observed, providing a physical connection between this pillar and the next.

The southern pillar (I.258), 6.7 m south of the middle pillar along the line of W.248, comprised three lower courses of dressed kurkar and an upper course of a large limestone monolith, 1.2×1.8×1.3 (Fig. 14)—i.e., 2.808 m3, with an estimated weight of around 7,612 kg. An upper part of what appears to be an additional monolith was discovered east of and adjacent to the southern pillar’s monolith. This structure may have been part of a wall approaching the southern pillar from the east. North of the southern pillar, the two remaining courses of the foundations of W.248 were of well-dressed kurkar stones, partially arranged as headers and stretchers. Some featured marginal signs of dressing (Fig. 15) and clearly belonged to spolia from an earlier Hellenistic building, located elsewhere. Considering the distance and physical connection between the surviving middle pillar and the northern pillar, one may assume that an additional pillar would have been required between them. The missing pillar (estimated to have been near Square FA30; see Fig. 10) was likely robbed in antiquity.

As a result of stone robbery, as well as seasonal rainfalls and landslides, earlier Hellenistic surfaces that originally abutted Wall 248 of the monumental building eroded and collapsed into the stone-robbers’ trench, where they were ultimately buried by sand (Fig. 16). Accumulations of eroded material from the floors were visible at the bottom of the trench and along its section. One of these, from a floor of the monumental building, yielded an especially rich assemblage in terms of restorable Hellenistic pottery and accompanying metal finds (L.252). Judging from the thick ash deposits on the floors, the charred organic materials and the variety of small finds and restorable vessels, the entire structure was destroyed by fire in the late 2nd century BCE.

Area D East features a single architectural unit—Building 5174—and a round installation (L.5066) (Fig. 17). Building 5174 is a rectangular structure (8×8.5 m), divided into three spaces, with mudbrick walls built on partially hewn beachrock stones. The northern wall consisted of five courses (ca. 7.7×0.9 m), which were cut into the Stratum III (Iron IIC) remains. The eastern and southern parts of the structure were poorly preserved and lacked evidence of a floor. Better preservation was attested in the southwestern corner (Square EA20), where a compacted, crushed, kurkar floor was uncovered. The accumulation above this floor contained Hellenistic pottery and several pieces of plaster. Below it, an additional patch of collapsed wall plaster appears to have sealed the occupational accumulation above an earlier floor containing several restorable vessels.

No evidence of a conflagration or deliberate destruction was found in Building 5174. This, combined with the limited ceramic assemblage, suggests that the building was probably deserted. However, the northern bounding wall of the structure is noticeably tilted southward and the entire building is tilted westward (Fig. 18). Coupled with the bad state of preservation, this phenomenon may be the result of a natural event — perhaps the earthquake postulated from the remains in Area A. The location and plan of the structure suggest that it served as a watchtower. Such an identification is supported by the impressive width and depth of its foundations, which must have supported a large superstructure (Fig. 19).

The circular, mudbrick-lined installation L.5066 is 37 cm deep and ca. 2 m in diameter, with a channel cut in its southern half. Like Building 5174, the installation penetrated earlier, Stratum III, remains. Although its function is unclear, it resembles a small silo or possibly a platform/foundation for a bread oven. Similar bread ovens, dating to the Hellenistic period, have been uncovered at Heliopolis and Tell Timai in Egypt (Hudson 2016: 210, Fig. 10). If this was indeed its intended function, the construction of this installation must have been left unfinished in antiquity, as there is no evidence of fire (e.g., ash or charcoal) in or around it.

Before dealing with our interpretation of the Hellenistic remains, it should be stated that the nature of the settlement at Ashdod-Yam during the preceding Persian period remains unclear, since only a few pottery sherds and some tentatively attributed metal finds from this period have been discovered on the acropolis so far.14 It is possible that the remains of any Persian-period settlement at Ashdod-Yam lie beyond the fortified perimeter of the acropolis, in areas not yet explored by our team. The Persian-period silver coins mentioned in this report (see above, n. 8) came from secondary contexts, either as unstratified finds or from contexts associated with the Hellenistic-period buildings. Whether these coins are connected to undiscovered contemporary remains or represent continued circulation in the Hellenistic period remains to be seen. Both scenarios are plausible.

The Hellenistic remains in Area A1 comprise the ruins of a monumental stone-built fortress likely constructed in the first half of the 2nd century BCE and destroyed towards the end of that century in a significant conflagration.15 The use of spolia (in the form of marginally dressed stones) suggests that there may have been earlier Hellenistic buildings nearby that were used for building material. Numerous artefacts—including pottery, coins, weaponry and weights—found in the building’s remains support the possibility that it had a military function and was perhaps the location of a garrison. Furthermore, two almost complete artillery stone balls were discovered in the vicinity (Fig. 27). Similar artillery balls, made of limestone, are known from Hellenistic contexts at Tel Dor (Shatzman 1995) and Antiochus VII Sidetes’ siege of Jerusalem (Sivan and Solar 2000; Ariel 2019: 31).

In contrast to the stone-built fortress, the contemporary adjacent structures in Areas A and D were constructed of mudbricks that either stood on stone foundations made of local beachrock or were laid directly on the sand. Moreover, these structures appear to have been abandoned and not destroyed by fire. Based on the proximity of Units 2 and 3 in Area A to the monumental structure in Area A1, it is plausible that they represent auxiliary buildings, which served various logistic functions related to the maintenance of the fortress. These buildings, located at the edge of the acropolis, may have been part of a protective fortification line that surrounded the entire military establishment, which included a mudbrick defensive wall discovered in Unit 1 in Area A. Part of this wall was established directly above the fortification line of the enormous Iron IIB rampart and incorporated several watchtowers detected along its southern line, the most impressive being the one discovered in Area D East. Fig. 28 offers a reconstruction of the settlement’s layout, which took advantage of the remains of the fortified Iron Age enclosure.

Geophysical surveys and archaeological investigations at Ashdod-Yam indicate that the acropolis and fortified enclosure in the southern part of the site were initially constructed and maintained during the Iron IIB–C (8th–7th centuries BCE) (Fantalkin et al. 2024). We suspect that these works protected an artificial anchorage established at the site (Fantalkin 2014; Lorenzon et al. 2023; Fantalkin et al. 2024), utilising and reconfiguring an existing estuary of the branch of Naḥal Lachish, which is not visible today. Over time, this once thriving anchorage fell into disuse, gradually becoming buried under accumulating sand.

The archaeological evidence shows that the acropolis at Ashdod-Yam was reoccupied during the Hellenistic period, after a long period of abandonment. Although the former Iron Age anchorage would no longer have been in operation, the establishment of a Hellenistic fortress with accompanying buildings and fortifications over the Iron Age settlement suggests the existence of some kind of mooring solution nearby. For example, merchant and military ships could have anchored offshore and used small row boats or barges to transfer goods and passengers from the moored vessel to the beach and back. In addition, certain ships would no doubt have been capable of landing directly on the shallow sandy beach at the base of Ashdod-Yam’s enclosure. The location of the fortress and the watchtower at the highest point of the acropolis may have also served as prominent landmarks for incoming ships.

In terms of the contemporary political environment, the establishment of the fortress and accompanying buildings at Ashdod-Yam during the first half of the 2nd century BCE should be viewed within the framework of Seleucid military activity. The shift to Seleucid rule in the area of Ashdod was most probably smooth and, in a sense, purely administrative, as was the case at other sites on the southern Coastal Plain of Palestine, such as Jaffa (Fantalkin and Tal 2008) and Ashkelon (Birney 2022: 3–11; see also Tal 2006: 177–216, 329). The remains of the relatively short-lived Hellenistic occupation at Ashdod‐Yam, detected so far only on the acropolis, most probably represent a mercenary garrison stationed there in the service of the empire. It is difficult to determine under precisely which Seleucid king the establishment of this military stronghold was commissioned. It was probably reinforced during the days of Antiochus VII Sidetes by his general Cendebaeus, who was appointed commander of the coast of Palestine and is said to have attacked Judaea from Iamnia (Yavneh-Yam), ca. 20 km to the north of Ashdod-Yam (1 Macc 15:38–40; cf. Josephus, AJ 13.225). Even though, according to 2 Macc 12:9, Judas Maccabaeus ‘attacked the Jamnites (Iamnitai) by night and set fire to the harbor and the fleet’, archaeological evidence demonstrates that the town continued to prosper following this event, being finally destroyed only as part of the conquests attributed to John Hyrcanus I towards the end of his reign or the beginning of that of Alexander Jannaeus (sometime around 110–100 BCE) (Fischer et al. 2023).

In contrast, a contemporaneous Hellenistic settlement at Gan Soreq, ca. 7.5 km northeast of Yavneh-Yam, which reached its greatest extent in the early 2nd century BCE, was abandoned already in the mid-2nd century BCE ('Ad and Dagot 2006), perhaps following the hostilities related to Judas Maccabaeus’ campaigns. A comparative Hellenistic settlement in the Barnea neighbourhood of Ashkelon, located ca. 4 km to the northeast of ancient Ashkelon (Haimi 2008), was established in the early 2nd century BCE and abandoned around the same time as the settlement in Gan Soreq or perhaps slightly later (Peretz 2017). The Hellenistic sequence at Ashkelon, however, suggests continuity through the 1st century BCE (Birney 2022: 10–11). Both the establishments at Gan Soreq and Barnea were interpreted by their excavators as possible katoikia, settled by Greek and/or Anatolian veterans and their families ('Ad 2021: 96–100).

The destruction by fire of the monumental stone building marked the end of the Hellenistic military settlement of Ashdod-Yam in the late 2nd century BCE (Area A1). Coinciding with the destruction of Tel Ashdod Phase 3b and the contemporaneous destruction at Yavneh-Yam, it is likely that these events are related and may be attributed to the campaigns of John Hyrcanus I towards the end of his reign.16 From the scarcity of finds, it is plausible that the auxiliary buildings (Area A) and the watchtower (Area D East) had already been cleared out by the defenders and abandoned before the fortress was destroyed. Perhaps considered too insignificant to burn down with the main edifice, the abandoned structures collapsed some time afterwards, possibly during an earthquake in the 1st century BCE or later (cf. Zohar, Salamon and Rubin 2016; Grigoratos et al. 2020). Following these events, the acropolis saw no further settlement, and over time, the once formidable walls of the fortress fell victim to extensive dismantling by stone robbers. Significantly, the numismatic evidence from the site aligns with these events. A notable gap in the coin record from the 1st century BCE and the absence of Roman coins from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE corroborates the hypothesis of a late 2nd-century BCE destruction and subsequent permanent abandonment of the Hellenistic military establishment on the acropolis. Consequently, the metal and ceramic artefacts from Stratum II, including those of Hellenistic type recovered from surface finds, can be confidently dated to the 2nd century BCE. Given Phase 3a at Tel Ashdod, which relates to the Hasmonaean occupation of the 1st century BCE, it is possible that this currently missing phase in Ashdod-Yam’s Hellenistic sequence is located elsewhere within the vast extent of the coastal site, beyond the perimeter of the fortified compound. Regardless, the precision in dating the Stratum II occupation on the acropolis of Ashdod-Yam offers a rare window into the life of a 2nd-century BCE coastal military settlement.

14 This is quite surprising given the prominent position of Ashdod during the Persian period,

mentioned specifically in Neh 13:23–24, although attested archaeologically only to a limited

extent at Tel Ashdod (Gitler and Tal 2006: 37).

15 For instances of contemporary military architecture in the Southern Levant, see Tal 2006:

138–163.

16 However, one cannot exclude the possibility that this wave of destructions took place at the

beginning of Alexander Jannaeus’ reign.

To encapsulate, the archaeology of Ashdod-Yam yielded the ruins of a monumental edifice most likely built in the first half of the 2nd century BCE and violently destroyed towards the end of that century. This massive stone construction found in Area A1, along with associated pottery, coins and weaponry, supports the interpretation that it had a defensive military function. Adjacent mudbrick structures, believed to be auxiliary to the main fortress, were, in contrast, not destroyed by fire but showed signs of having been abandoned followed by a collapse, perhaps as the result of an earthquake. Ashdod-Yam’s strategic significance during the Hellenistic period appears relatively emphatic: a garrison was likely stationed there as part of the Seleucid empire’s control of the territory, later contested by Hasmonaean forces. The destruction of the monumental stone fortress and the abandonment of the auxiliary buildings likely took place during the Hasmonaean consolidation of power under John Hyrcanus I. The end of Hellenistic Ashdod-Yam frames a dynamic period of conflict and transition in the region. Further research is needed to bring to light the full archaeological narrative of Ashdod-Yam, particularly its role in the era of Hasmonaean occupation.

- Fig. 5 - Plan of excavated Byzantine

Church Complex from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of the excavated complex and location of the inscriptions

(created by Slava Pirsky and Liora Bouzaglou)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Orthophoto of excavated Byzantine

Church Complex from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

The orthophoto of the excavated complex

(created by Slava Pirsky and Sergey Alon)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 21 - Destruction debris in the Byzantine

Chapel from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

The destruction debris during the excavations of the chapel in Unit 5

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Fig. 22 - Destruction debris in the Byzantine

nave from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

The destruction debris during the excavations of the nave in Unit 2

(photo taken by Sasha Flit)

Di Segni et al. (2022)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls | Area A and D

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Aerial view of the acropolis (looking south) in 2013, showing the excavated areas (photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; modified by S. Pirsky) Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28Reconstruction of the Stratum II settlement (drawing by S. Pirsky) Fantalkin et al. (2024b) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall (Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography) Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Unit 1 in Area A: W.117, built of mudbricks directly on sand, looking northeast (photo by P. Shrago) Fantalkin et al. (2024b) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls and roof Debris |

Unit 2 (Nave) and Unit 5 (N Aisle)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Plan of the excavated complex and location of the inscriptions (created by Slava Pirsky and Liora Bouzaglou) Di Segni et al. (2022) |

Fig. 22

Fig. 22The destruction debris during the excavations of the nave in Unit 2 (photo taken by Sasha Flit) Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21The destruction debris during the excavations of the chapel in Unit 5 (photo taken by Sasha Flit) Di Segni et al. (2022) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls | Area A and D

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Aerial view of the acropolis (looking south) in 2013, showing the excavated areas (photo by P. Partouche, Skyview Photography; modified by S. Pirsky) Fantalkin et al. (2024b)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28Reconstruction of the Stratum II settlement (drawing by S. Pirsky) Fantalkin et al. (2024b) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Hellenistic remains in Area A, showing the mudbricks still in situ and the mudbricks that have collapsed from the upper portion of the wall (Credit: Pascal Partouche, Skyview Photography) Lorenzon et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Unit 1 in Area A: W.117, built of mudbricks directly on sand, looking northeast (photo by P. Shrago) Fantalkin et al. (2024b) |

|

VIII+ |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls and roof Debris |

Unit 2 (Nave) and Unit 5 (N Aisle)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Plan of the excavated complex and location of the inscriptions (created by Slava Pirsky and Liora Bouzaglou) Di Segni et al. (2022) |

Fig. 22

Fig. 22The destruction debris during the excavations of the nave in Unit 2 (photo taken by Sasha Flit) Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21The destruction debris during the excavations of the chapel in Unit 5 (photo taken by Sasha Flit) Di Segni et al. (2022) |

|

VIII + |

Darvasi, Y. et al. (2024) An early Byzantine ecclesiastical complex at Ashdod-Yam: correlating geophysical prospection with excavated remains,

STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research, Volume 10, 2024 - Issue 1 - open access

Di Segni, L., Bouzaglou, L., and Fantalkin, A. (2022) A Recently Discovered Church at Ashdod-Yam (Azotos Paralios) in Light of Its Greek Inscriptions

Liber Annus 72 (2022) 399-447

Dothan, M. (1973) The foundation of Tel Mor and of Ashdod (IEJ, V23, 1973) - JSTOR

Fantalkin, A. (2023) Azotos Paralios (Ashdod-Yam, Israel) during the Periods of Roman and Byzantine Domination: Literary Sources vs. Archaeological Evidence

In: Horn, C. and Bäbler, B. eds. Wort und Raum. Religionsdiskurse und Materialität im Palästina des 4.– 9. Jahrhunderts n. Chr.

Fantalkin, A. et al. (2024) Iron Age Remains from Ashdod-Yam: An Interim Report (2013–2019)

Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies v. 12 no. 3

Fantalkin, A. et al. (2024) Hellenistic Ashdod-Yam in Light of Recent Archaeological Investigations

, Tel Aviv, 51:2, 238-278

Lorenzon, Marta, Cutillas-Victoria, Benjamin, Itkin, Eli, and Fantalkin, Alexander (2022) Masters of mudbrick: Geoarchaeological analysis of Iron Age earthen public buildings at Ashdod-Yam (Israel)

Geoarchaeology 2023:1-28

Meimaris Y. E. Βούγια Π Bougia P. & Κριτικάκου Ε. (1992). Chronological systems in roman-byzantine palestine and

arabia : the evidence of the dated greek inscriptions. Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity National

Hellenic Research Foundation = Κεντρον Ελληνικης και Ρωμαικης Αρχαιοτητος Εθνικον Υδρυμα Ερευνων ; Diffusion de Boccard.

Vunsh, R., Tal, O., and Sivan, D. (2013) Horbat Ashdod-Yam Preliminary Report

Hadashot Arkheologiyot Volume 125 Year 2013

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica: The Library, Books 16–20: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Successors (a new translation by Waterfield, R.). Oxford, 2019.

Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Volume V: Books 12–13 (Marcus, R., trans.; Loeb Classical Library 365). Cambridge, MA. 1943; Volume VI: Books 14–15 (Marcus, R. and Wikgren, A., trans.; Loeb Classical Library 489). Cambridge, MA, 1943.

Josephus, The Jewish War, Volume I: Books 1–2 (Thackeray, H.St.J., trans.; Loeb Classical Library 203). Cambridge, MA, 1927.

1 Macc 1 Maccabees. A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (by Schwartz, D.R.; The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries). New Haven and London, 2022

A. Berman et al., Map of Ashdod (84) (Archaeological Survey of Israel), Jerusalem

2005.

J. Kaplan, ABD, 1, New York 1992, 482

I. Finkelstein & L. Singer-Avitz, TA 28 (2001), 246–254.

S. Gibson, PEQ 131 (1999), 124

D. Nachlieli et al., ESI 112 (2000), 101*–103*

H. Tadmor, JCS 22 (1958), 70-80

J. Kaplan, IEJ 19 (1969), 137-149

L. Y. Rahmani, ibid. 37 (1987).

133-134