Jerash - JWP115 Landslide

Figure 2.15a

Figure 2.15a

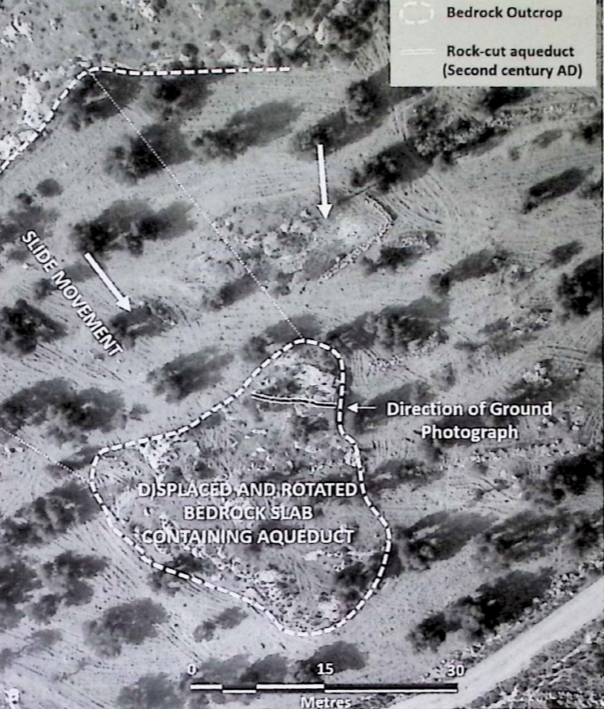

Landslide at site JWP 115. Aerial view, looking south, showing the bedrock slab containing a section of aqueduct JW01 displaced from the outcrop upslope to the south

(APAAME_20170927_DDB-0156, photo by author)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Boyer in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Chat GPT 5.1, 20 November 2025

- sources: Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Although some landslides are prehistoric, many date to Antiquity and Late Antiquity and can be linked to seismic episodes along the Dead Sea Transform Fault Zone. Examples such as the Bab Amman landslide, the Ficus Springs rotational slide, and the displacement of the northwest aqueduct at JWP115 demonstrate how earthquakes detached entire hillside blocks, severed spring–aqueduct connections, reversed aqueduct gradients, and buried or dislocated terracing soils. While often devastating locally, these events did not uniformly cripple the region; in many cases, ancient and modern farmers re-terraced landslide surfaces and continued to cultivate them, reflecting a longstanding pattern of resilience within a dynamic and hazard-prone landscape.

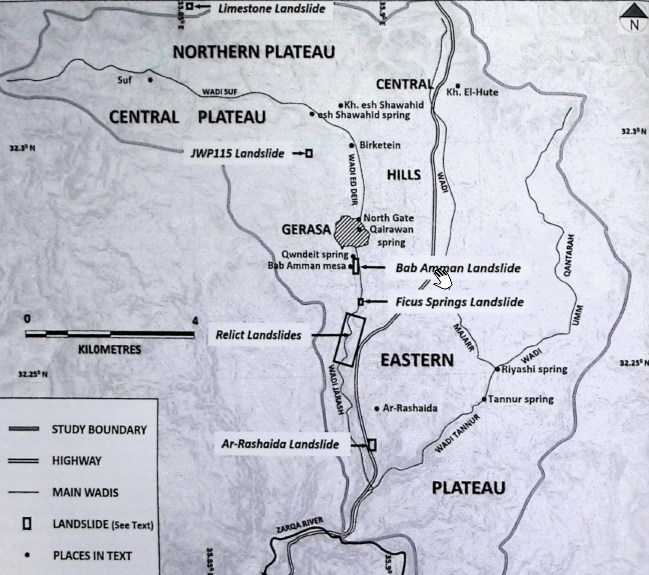

- Fig. 2.2 Location Map

from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.2 Location Map

from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Jerash - Site JWP115 in Google Earth

- Jerash - Site JWP115

from APAAME site on flickr

Jerash - Site JWP115 from APAAME site on flickr

Jerash - Site JWP115 from APAAME site on flickr

click on image to open in a new tab

Jarash Channel 16 (JWPS 115)

Reference: APAAME_20170927_DDB-0156

Photographer: David Donald Boyer

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works - Fig. 2.15a Aerial View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Jerash - Site JWP115 in Google Earth

- Jerash - Site JWP115

from APAAME site on flickr

Jerash - Site JWP115 from APAAME site on flickr

Jerash - Site JWP115 from APAAME site on flickr

click on image to open in a new tab

Jarash Channel 16 (JWPS 115)

Reference: APAAME_20170927_DDB-0156

Photographer: David Donald Boyer

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works - Fig. 2.15a Aerial View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

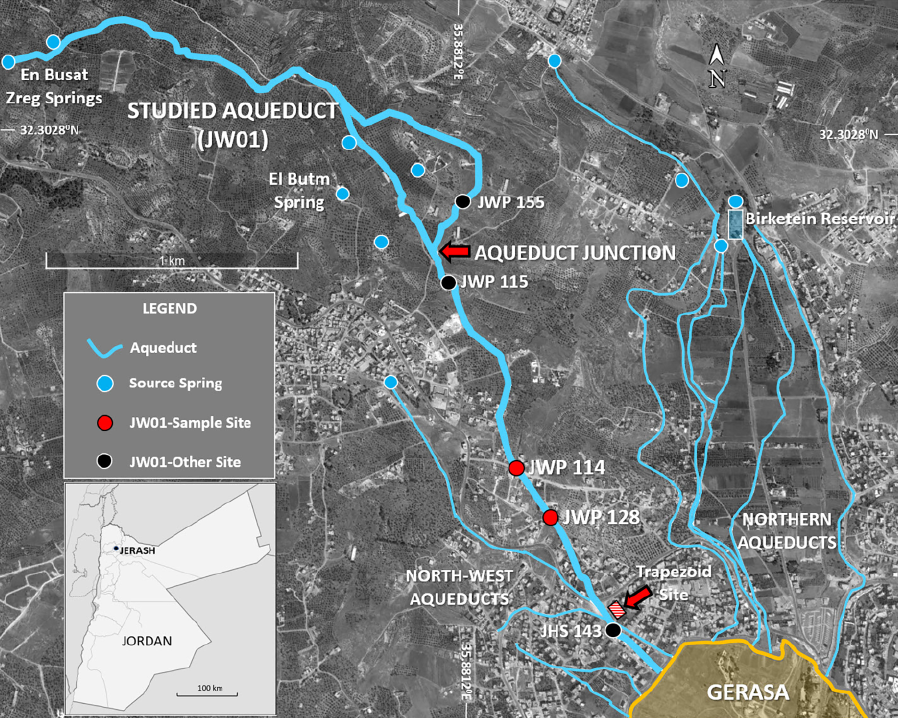

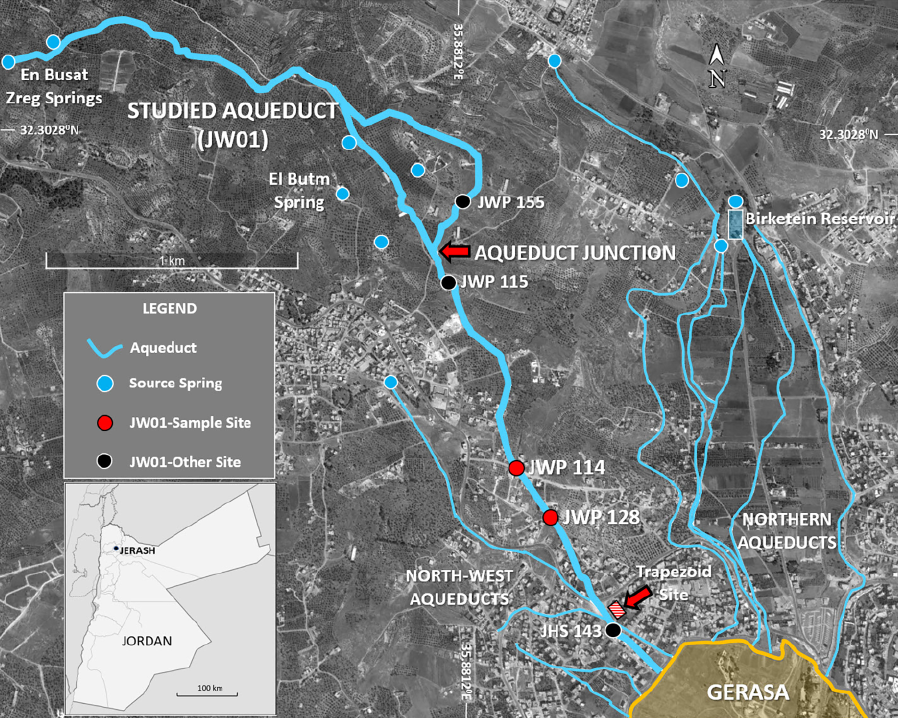

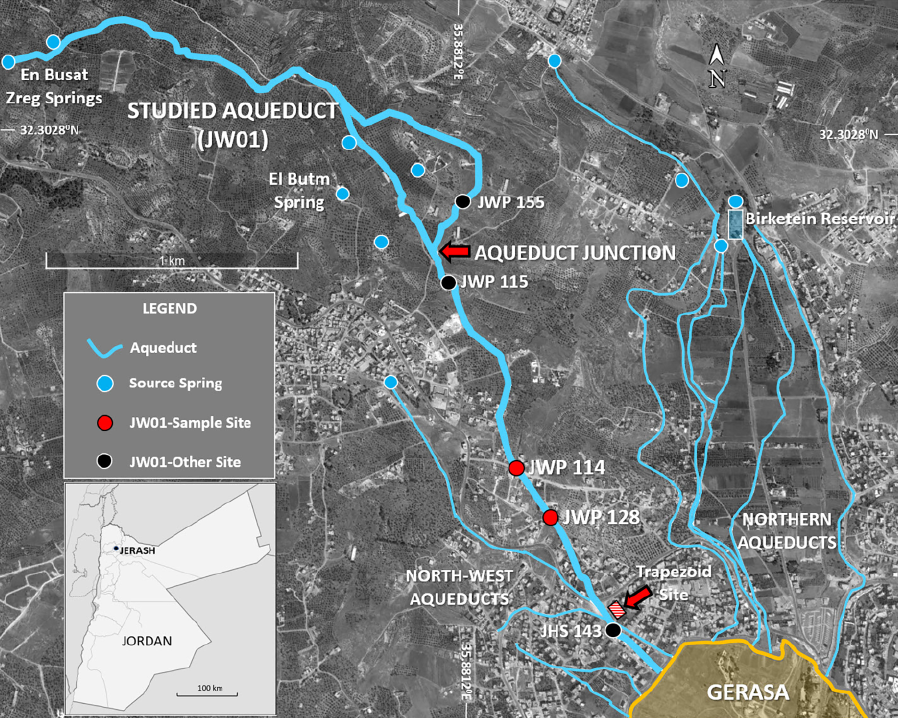

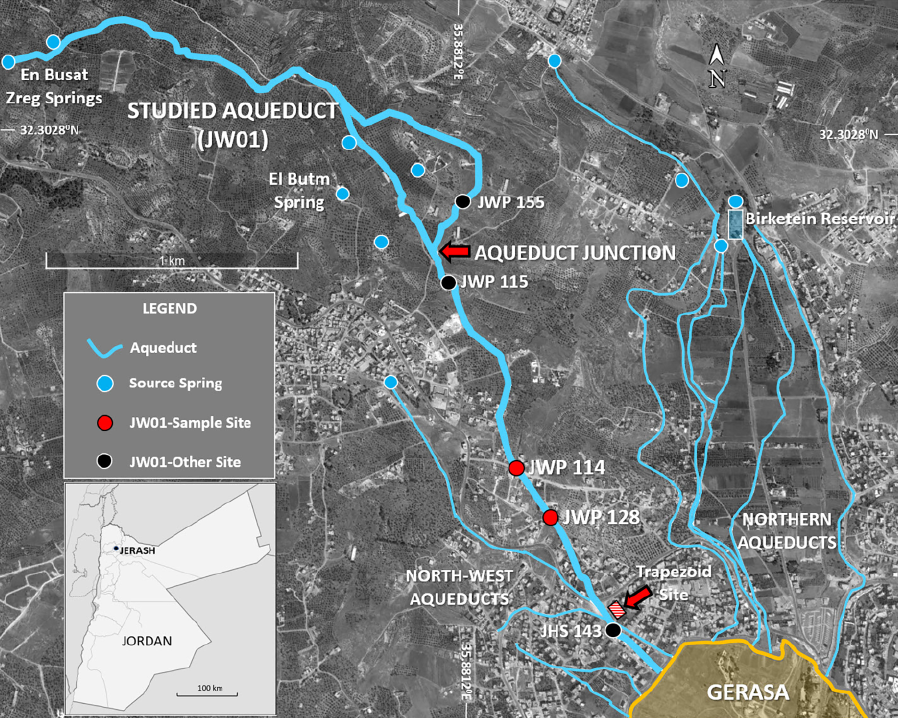

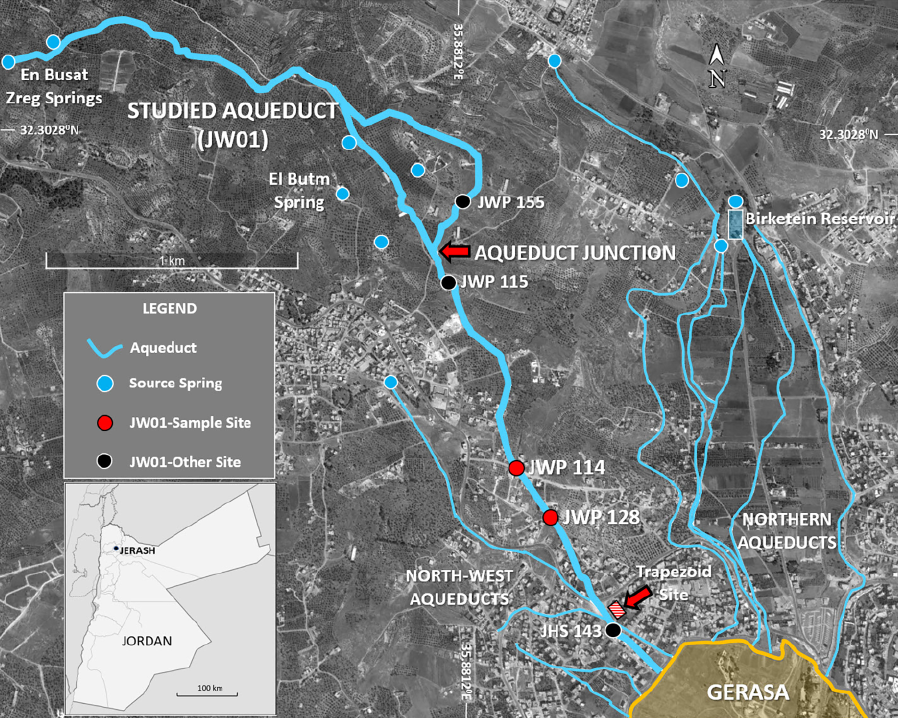

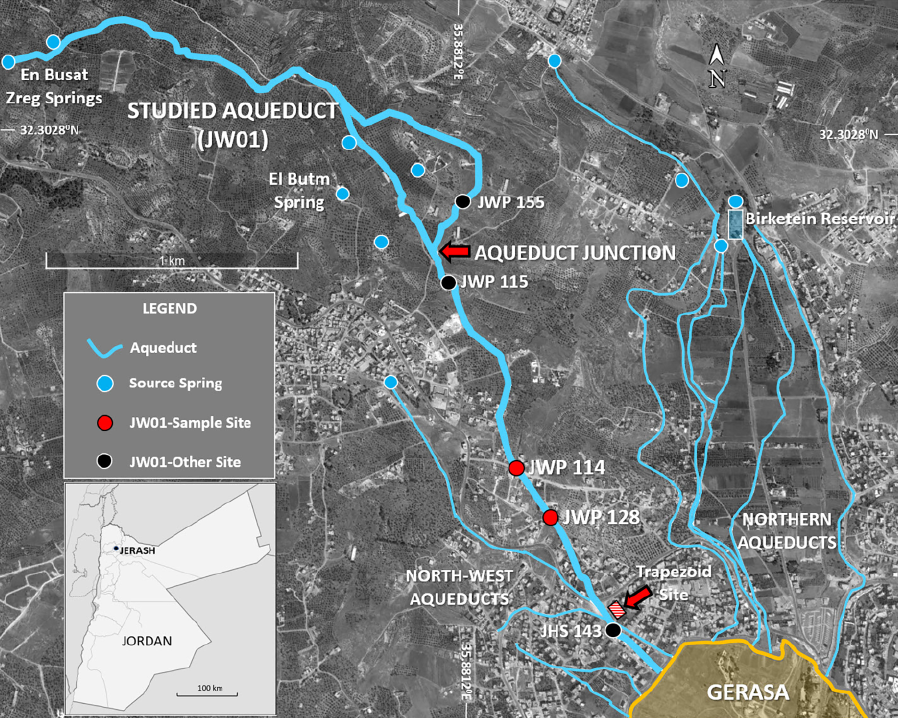

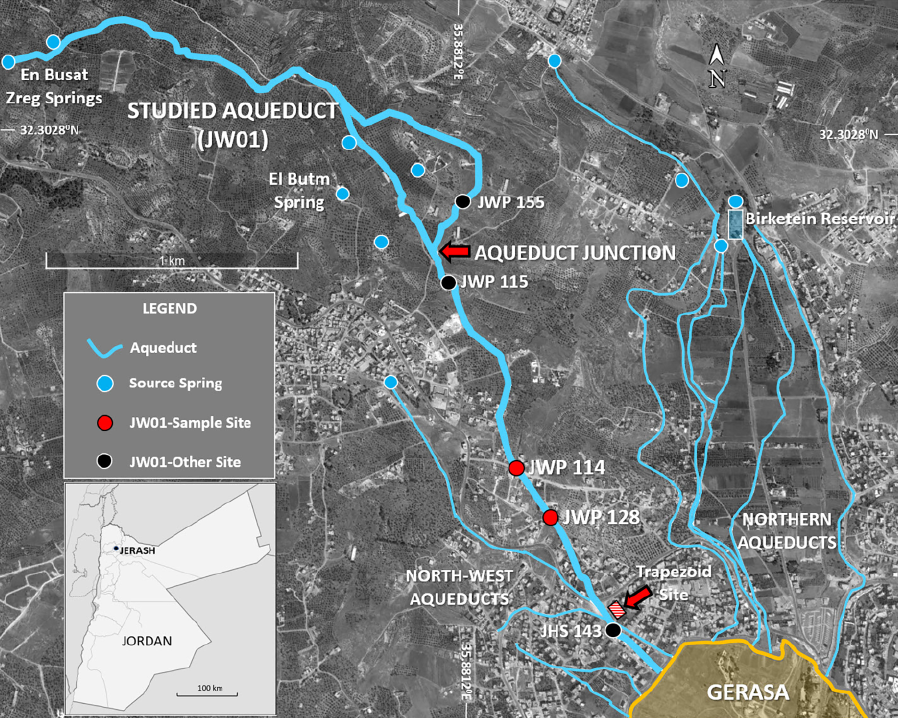

- Fig. 1 Northern and

North-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs from Passchier et al. (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Passchier et al. (2021)

- Fig. 1 Northern and

North-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs from Passchier et al. (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Passchier et al. (2021)

- Fig. 2.15a Aerial View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.15b Ground View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 showing the rock-cut aqueduct section preserved in the displaced bedrock slab from Boyer in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.15a Aerial View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.15b Ground View of

Landslide at site JWP 115 showing the rock-cut aqueduct section preserved in the displaced bedrock slab from Boyer in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

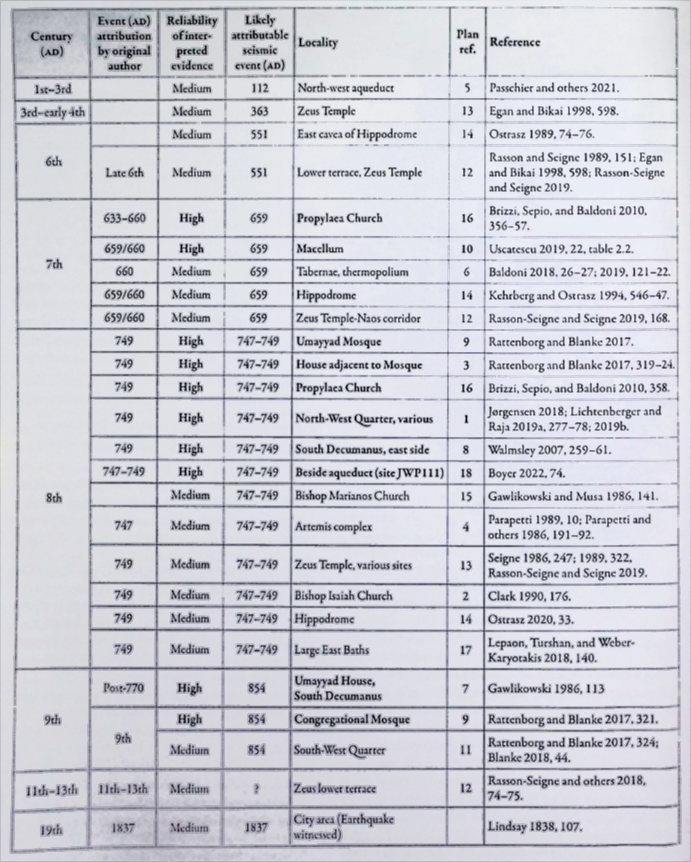

Natural resources can be impacted by various forms of downslope earth movements on unstable slopes triggered by seismic shaking and faulting. The resulting damage can be in the form of dislocation or burial in the case of water-related infrastructure, while soils can be impacted by burial or damage to agricultural terracing.

There is abundant evidence of landslides in Jerash's hinterland: some sites are shown on the published geological map, but many more are visible in the modern landscape, particularly in the lower Jerash Valley.31 Landslides are the largest type of downslope earth movement under gravity (mass wasting) and consequently have the potential to be particularly damaging to natural resources and have been a feature in the landscape since the beginning of landscape formation in the area. Landslide-prone areas in the vicinity of Jerash are associated with steep slopes (> 10 degrees), especially close to wadi beds in the lower Jerash and lower Majarr-Tannur Valleys, where slopes are frequently > 25 degrees. Figure 2.11 shows the distribution of zones highly susceptible to landslide risk downstream of Jerash derived from recent research.32

Landslides in the study area can be triggered by seismic events and heavy rainfall, and the impacts on natural resources can be equally damaging. It is not always possible to determine the nature of the triggering event, but recent landslide research has shown that Kurnub sandstone bedrock areas in the lower Jerash and Majarr-Tannur Valleys are particularly prone to landslides induced by heavy rainfall. The landslide risk in these areas is enhanced by a combination of factors that includes very steep slopes, unstable claystone horizons, springs, and previous earth movements, but heavy rainfall is the key trigger.33

Landslides in the area can be divided into three groups — relict, dormant, and active — based on their activity level.34 Examples of relict pre-Holocene landslides can be seen throughout the Jerash Valley. Well- preserved examples exist downstream of Jerash, their age indicated by the thick accumulations of terrace soils on the surface of the main bodies of displaced material that have been farmed since Antiquity (Fig. 2.12a). Younger but dormant landslides dating to Antiquity and Late Antiquity are common but are often obscured by subsequent farming activity and earth movements (Fig. 2.12b). The youngest landslides remain active and can be found in limestone (Fig. 2.12c) and sandstone (Fig. 2.12d) terrains.

Three examples of dormant landslides will be described to show the impact of landslides on water infrastructure. The best-studied dormant landslide to date is located on the eastern slope of the Bab Amman mesa south of Jerash (Bab Amman landslide). This seismically induced translational slide involved the detachment of a c. 500 m long section of the eastern slope of the mesa (Fig. 2.13).

The detachment occurred at the break in slope marking the eastern edge of the mesa summit and was partly facilitated by the existence of a deep rock-cut aqueduct at site JWP147a that acted as an artificial point of weakness.35 Part of the backscarp of the slide runs along the specus of this aqueduct just south of Qwndeit spring. This spring supplied a cluster of ancient aqueducts cut into calcretized Jerash Conglomerate bedrock along the steep eastern slope of the mesa that supplied fields at the southern end of the mesa in the vicinity of the Tell Abu Suwwan Neolithic settlement.36 The landslide removed a large section of the hillside carrying these aqueducts, but a section is still preserved on the southern flank of the landslide.

The second example is a small rotational landslide in the Jerash Valley at Ficus Springs, 2 km south of Jerash. The Kurnub sandstone springs at this site were important water sources in prehistoric and historical times, supplying several rock-cut aqueducts on the eastern bank of Wadi Jerash. A rotational rockslide removed a c. 30 m long section of the sandstone cliffs, separating the sources from the aqueducts they supplied. The slide occurred at the intersection of bedrock joint sets (Fig. 2.14a), including a set of curvilinear joints peculiar to this locality. Several movement phases are indicated by the surface patina on bedrock within the perimeter of the landslide. The site is covered by soil derived from recent soil creep on the steep slope above the landslide (Figs. 2.14b).

In the case of the third landslide example, located in the hills west of the city (site JWP115), a seismically induced landslide detached a section of hillside carrying the north-west aqueduct (“JW01”), which was an essential early aqueduct to the city (Fig. 2.15).37

The landslide carried the detached section c. 40 m downslope, and the rotation of the detached block reversed the original aqueduct gradient. The dating of charcoal in the youngest plaster lining the specus of the same aqueduct downstream at site JWP128 provides a poorly constrained early second- to early fourth- century AD date for the timing of the landslide.38 The first major seismic event to have likely impacted the city after this date was in AD 363. If the damage occurred whilst the aqueduct was in operation, it would have resulted in the immediate and permanent loss of the JW01 aqueduct alignment.

Seismic events can also induce soft-sediment subsidence through liquefaction. Evidence of historical liquefaction is not common and has not previously been reported from the Jerash area; however, the subsidence of the masonry pier of a canal supplying a penstock- type watermill at Ficus Springs of probable medieval date may be attributed to liquefaction. The penstock was built into the wadi bed, and the extant medieval masonry canal replaced a structure destroyed by an earlier event. The pier foundations were set in poorly consolidated wadi sediments, and there is clear evidence that the pier subsided vertically, causing the partial collapse of the crowns of the adjoining arches (Fig. 2.16). Given the location in the wadi bed, it is also possible that the subsidence was caused by the saturation of the wadi sediments by normal wadi flow.

An understanding of seismically induced impacts on soils is hampered by the difficulty of discriminating between seismically and run-off-induced soil impacts. Landslides and other forms of mass wasting induced by heavy rainfall would have been the most severe historical events to impact soils via the threat to agricultural terracing, a concern that continues today. A seismic event could potentially exacerbate run-off- induced damage if it occurred during the winter wet season, and mass wasting may have accompanied the AD 747, 1293, 1546, and 1837 events that all occurred in January.

While there is abundant evidence of landslides and other forms of mass wasting such as debris flows and sheetflood gravels in the Jerash area, the relatively small areas impacted by these events meant that their impact on the soil resources was not necessarily catastrophic in the overall context of the city's hinterland. Indeed, considering the district's reliance on dryland farming, the same heavy rainfall events that caused problems to soil-retaining infrastructure on steep slopes could have had a beneficial effect in soils developed on plateau tops and shallower slopes by enhancing soil moisture levels. The impact of earth movements on unstable slopes is also often only temporary. Aside from the use of terrace soils on relict landslide surfaces already mentioned, there are many examples of the surfaces of dormant landslides being re-terraced and brought back into agricultural use. There are modern examples of active landslides treated similarly, especially in the lower Jerash and Majarr-Tannur Valleys. This acceptance of the risks associated with the reuse of areas impacted by landslides may well be echoed in the seemingly persistent placement of aqueducts on the edge of cliffs and escarpments in Antiquity.

31 The most comprehensive geological map is that by AbdelHamid, 1995/

32 Awawdeh, El Mughrabi, and Atallah 2018.

33 Malkawi and others 1998. 19; Farhan 1999; Boyer 2022, 82-88.

34 Alter Cruden and Varnes 1996.

35 Boyer 2022, 406-08.

36 For derails of Tell Abu Suwwan, see Al-Mahar 201S.

37 Boyer 2022, 397-402.

38 Boyer 2022, 351, table DI (Sample B-417372). The first major seismic event likely to have impacted the area after this date was in AD 363.

- from Boyer (2022:71)

The DST comprises several fault segments, and the section lying closest to Gerasa is known as the Jordan Valley fault.138 Movement along the DST relieves stresses that build up in the adjacent rocks, and this relief manifests itself in the form of earthquakes that can be very severe. While the majority of earthquake epicentres lie within the DST, a few have been recorded in neighbouring areas that encompass the Decapolis. The earthquake record for the DST and the region has been compiled from an assessment of written historical sources, archaeological evidence, and geotechnical and archaeometric data and has been the subject of intensive research and debate for decades.139 A review of the research shows that earthquake studies are fraught with challenges. Evidence from contemporary records, inscriptions, archaeology, and geology is rarely concurrent, and is often scant. Not all seismic events leave an obvious trace, and, as a consequence, the chronological record is incomplete. The problem is compounded by archaeological records that frequently lack the detail to distinguish destruction due to seismic events from destruction resulting from other sources such as warfare, looting, natural decay, or deliberate dismantling.140 The details of a number of major earthquakes are disputed, a point reinforced by the latest catalogue of major earthquakes in the vicinity of the Dead Sea Transform, which not only lists many new earthquakes but places the epicentre of the AD 749/50 events in northern Syria rather than Palestine.141 The distribution of well-attested major earthquakes in the Jordanian region in the period 31 BC to AD 1900 based on the latest published earthquake catalogue is shown in Figure 3.35.

138 Ferry and others 2011, 39, fig. 1.

139 For the most recent studies, see Ken-Tor and others

2001; Ferry and others 2011; Yazjeen 2013; Wechsler and

others 2014; El-Isa, McKnight, and Eaton 2015; Zohar,

Salamon, and Rubin 2016; Grigoratos and others 2020. For

an earlier study, see Russell 1985.

140 The late nineteenth-century Russian traveller Prince

Abamelek-Lazarev observed `besides the earthquakes, wars

frequently also turned thriving cities into heaps of ruins;

and more destructive than weather on the ancient monuments

has been the slow looting thereof. The following

generations used them as raw materials for building new

projects, and the denser the population, the higher the

culture, the greater the luxury of the monuments of past

times, the greater was the danger of the ancient monuments

being destroyed' (1897, 8) (translated from the original

Russian).

141 Grigoratos and others 2020, 821-22.

- from Boyer (2022:71-72)

142 For commentary on the geological evidence of seismic

impacts in the local landscape, see Boyer 2018d,

especially 61-64. The city was one of several Jordanian

sites included in an early study by El-Isa (1985). El-Isa

provided a list of major earthquakes that affected the

city and, unusually, estimated peak ground acceleration

parameters, but the conclusions have been largely

superseded by more recent research.

143 The only historical eyewitness record of an earthquake

in Jarash relates to the January 1837 earthquake witnessed

by George Moore and reported by Lindsay (1838, 107).

- from Boyer (2022:72-77)

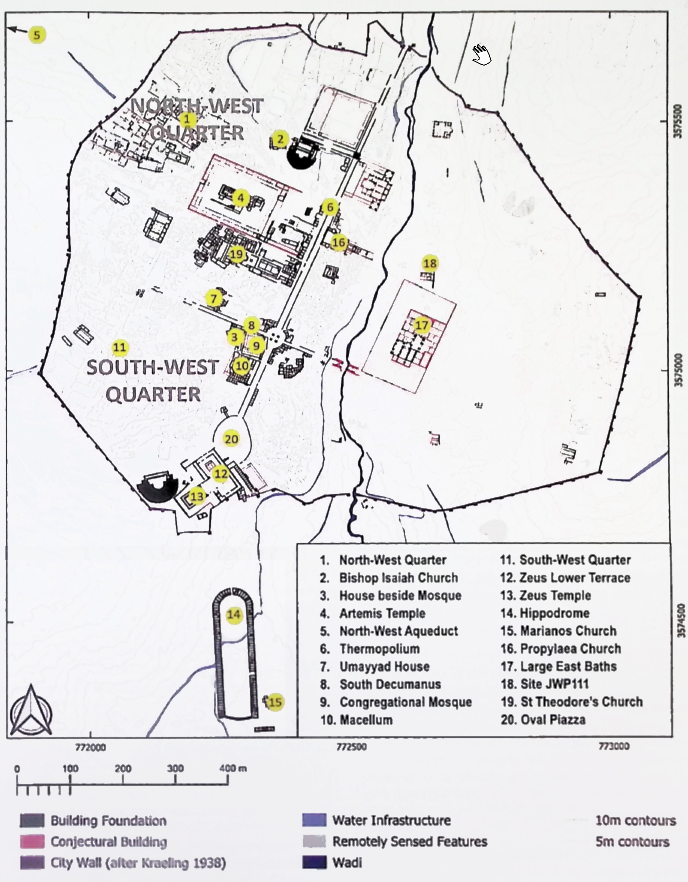

- High reliability: significant earthquake destruction, sealed archaeological contexts, and reliable chronology.

- Medium reliability: significant earthquake destruction, some chronological constraint, but sealed context doubtful or uncertain.

- Low reliability: destruction not necessarily seismic-induced, no dating evidence or only vague chronological constraint, no sealed context, or generally where there is uncertainty over the reliability of the data.

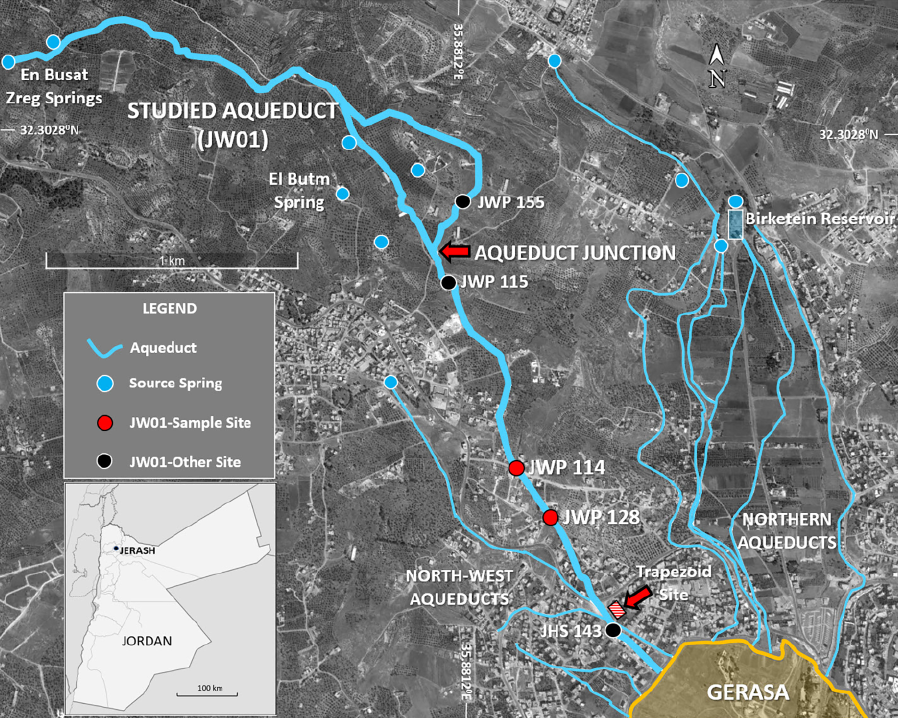

The results show that evidence supporting individual earthquake events is often poorly constrained chronologically, and evidence from sealed and well-dated archaeological contexts is available for only a few sites. The most reliable evidence relates to events in the mid-seventh and mid-eighth centuries; evidence of pre-sixth-century earthquakes is both sparse and, with two exceptions, of low reliability. The higher proportion of references to the younger seismic events is influenced by factors such as the limited extent of excavation to Roman levels and the tendency for the foundations of later buildings to be taken down to bedrock, thus removing any evidence of earlier seismic damage.

There is no published evidence of earthquake damage in the city before the third century; however, it has been speculated that the rebuilding of the North Gate in AD 115 followed an earthquake event in the early second century.144 If so, then the most likely event was the AD 112 earthquake with an epicentre west of the Dead Sea. The c. second-century plastering events recorded at several sites along the main north-west aqueduct (JW01) in the present study may possibly reflect damage from the same event.145 Aside from damage to the North-West Quarter in the third–early fourth centuries, there is little reliable evidence of strong earthquake activity in the third- to the fifth-century period affecting buildings in the central part of the city, and although there are several attributions to the AD 363 earthquake episode, the evidence cannot be confidently attributed to any particular regionally attested event.146 The study found evidence of the ruination of columns on the Artemis Temple podium and the deposition of column drums onto the adjacent natural rock surface of the Artemis upper terrace that probably dates to the early period following the spoliation of the temple in the fourth–early fifth centuries.147 The ruination of structures on the west side of the Nymphaeum and the subsequent construction of a quadriporticus on top of these ruins also appears to predate the mid-fifth century.148 These findings hint at the possibility that earthquake damage to the city in the fourth–early fifth centuries was more severe than previously supposed and may be associated with the AD 418 event that impacted Palestine.149

The most significant impacts on the city, and the southern Decapolis region as a whole, occurred in major seismic episodes that recurred at c. one hundred-year intervals between the mid-sixth and mid-eighth centuries, and in particular, the mid-seventh- and mid-eighth-century events. There is an increase in references to damage from the sixth century, and especially the mid to late sixth century, but the reliability is generally poor, and the destruction is limited in extent across the city. Some of this damage could conceivably have been associated with the major AD 551 earthquake episode, estimated to have had a movement magnitude of 7.5, which caused widespread damage along the Lebanese littoral and to a lesser extent inland, but the epicentre is c. 200 km from Gerasa.150 The collapse of the floor of the large reservoir (Reservoir 1; see Chapter 7) in the city's North-West Quarter in the fifth or sixth century was likely caused by a substantial shock, but this damage has not been attributed to a specific seismic event by the excavators.151

Earthquake events in the seventh century caused widespread and well-documented damage across the city between the Hippodrome and the West Propylaea. Evidence from the Macellum and Propylaea Church is considered to be reliable and is attributed by the excavators to earthquake events in AD 633 or AD 659/60, but the majority of excavators attribute the earthquake damage to the so-called AD 659/60 seismic episode.152 This episode is now considered to have comprised two separate events two days apart in June AD 659 that affected Palestine and, to a lesser extent, Syria.153 Although there appears to be no support for this event affecting the Decapolis from literary sources, there is convincing archaeological evidence for earthquake damage around the mid-seventh century for the western side of the city.

The effects of earthquakes in the mid-eighth century were felt in all the cities of the southern Decapolis, and there is substantial evidence of earthquake damage in Gerasa related to these events. The Gerasene references attribute the damage to events that range in date from AD 717 to AD 749. While the majority of the more recent references attribute the damage to an event in January AD 749, the evidence only supports an approximate mid-eighth-century date and does not preclude the possibility of several separate but closely spaced events. Tsafrir and Foerster argued that events previously dated to AD 746/47/748 actually refer to a major event in January AD 749;154 however, the matter is not settled, as is shown by evidence for three separate seismic episodes affecting the region between AD 746–757.155 The Gerasene sites with damage from the mid-eighth-century seismic episode are found throughout the excavated parts of the western side of the city, and the reliability of the evidence is medium to high in the majority of cases. While evidence from the South-West Quarter is sparse for the study period, it seems likely that the mid-eighth-century earthquakes affected the entire western side of the city. Particularly reliable evidence is available for sites in the North-West Quarter and in the South Decumanus–South Tetrakionion precinct, where the suddenness of earthquake impact on domestic life is dramatically represented in the archaeological record.156 Evidence from the eastern side of the city is currently limited to two sites. The first site was identified in the study adjacent to the substructio carrying the Qairawan aqueduct. The site (JWP111) was briefly exposed during foundation excavations for a new building, and radiocarbon dating of charcoal from horizons above and below a tumble horizon up to 2 m thick over a low, ruined masonry structure (possibly an early water channel) indicated that the tumble dates to the mid-eighth century period (Fig. 3.37). The second site is the Large East Baths, where earthquakes are said to have caused ‘a brutal and almost complete destruction of the monument’.157

Whatever the actual date of the seismic episodes of the mid-eighth century, the damage they caused was substantial. The massive damage to the Large East Baths and the damage evidenced in domestic buildings around the South Tetrakionion and the North-West Quarter show that buildings both large and small were dramatically affected. Evidence from the North-West Quarter shows that this part of the city was devastated and abandoned after the mid-eighth-century earthquakes and not reoccupied until the Ayyubid–Mamluk period;158 however, evidence from the vicinity of the Umayyad Congregational Mosque in the central city area shows that this part of the city was resettled shortly after these earthquakes.159

The catalogue published by Grigoratos and others includes many significant seismic events (i.e. Mw > 6) in the region after the mid-eighth century. Earthquake damage has been identified in the city's South-West Quarter dating to the late ninth–early tenth centuries,160 and Seigne and Tholbecq attributed a destruction layer on the lower terrace of the Zeus Temple to an earthquake around AD 1200.161 As already noted, an earthquake affecting the city in January 1837 was witnessed by a European visitor, George Moore.

The clearances of the 1920s and 1930s and subsequent building restorations have removed much of the visible evidence of structural damage to buildings in the city; however, there is sufficient evidence from historical photographs and from surviving unrestored buildings to provide an overview of the types of damage incurred. Large-scale damage in the form of groups of columns falling in the same direction was revealed in the excavation of St Theodore and Synagogue Churches by the Yale Mission (Figs 3.38a-3.38b), and similar evidence has been reported from churches elsewhere in the Decapolis.162 Smaller-scale impacts of horizontal shear stress on columns are preserved in the colonnades surrounding the Oval Piazza and on the Artemis podium (Figs 3.39a-3.39c), and there are also examples of the vertical rotation of Ionic capitals of up to seventy degrees in the western colonnade of the piazza (Figs 3.40a-3.40b).

Mortar was rarely used on the larger city buildings, and there are many examples of seismically induced block separation, especially in masonry pilasters and columns (Figs 3.41a-3.41b). Seismically induced shearing is also evident across ashlars in extensive walls such as those forming the Artemis cella (Fig. 3.41c).

144 Russell 1985, 41. The construction was dedicated to

Trajan in an inscription (Welles 1938, 401, nos 56–57).

145 Passchier and others 2021.

146 For commentary on the AD 363 earthquake, see Russell

1985, 42; Ambraseys 2009, 158–61.

147 The various building components of the Artemis Sanctuary

are inconsistently described in the corpus. In Kraeling

(1938a) and earlier publications of the Italian team

investigating the sanctuary (for example Parapetti 1995),

the terrace on which the Artemis podium and cella were

built was referred to as the temenos or ‘temple terrace’

or ‘temple court’, and the terrace between the West

Propylaeum and the temenos was referred to as the

‘intermediate terrace’. Temenos was later replaced by

‘upper terrace’ and ‘intermediate terrace’ was replaced by

‘lower terrace’. The use of upper terrace and lower

terrace is adopted henceforth in this volume. The

locations of these localities and others related to the

Artemis Sanctuary are taken from Brizzi 2018, fig. 6.1.

148 Brenk 2015.

149 Ambraseys 2009, 162.

150 Russell 1985, 44–46; Darawcheh and others 2000;

Sbeinati, Darawcheh, and Mouty 2005, 357–59; Ambraseys

2009, 199–203; Grigoratos and others 2020, 821.

151 Lichtenberger and others 2015, 120–23.

152 Russell 1985, 51–55; Ambraseys 2009, 221–22. For details

of the AD 633/34 earthquake, see Sbeinati, Darawcheh, and

Mouty 2005, 360; Ambraseys 2009, 219–20.

153 Russell 1985, 46–47; Ambraseys 2009, 221–22. Grigoratos

and others (2020) found evidence of an earthquake event

(H659b) with a different epicentre in September AD 659.

154 Ambraseys 2009, 230–38; Russell 1985, 47–49; Tsafrir and

Foerster 1992; Marco and others 2003; Sbeinati, Darawcheh,

and Mouty 2005, 362–64.

155 Ambraseys 2009, 234–38; Grigoratos and others 2020,

821–22.

156 Walmsley 2007, 259–61; Jorgensen 2018; Lichtenberger and

Raja 2019e. For similar evidence in Pella, see Walmsley

2007.

157 Lepaon, Turshan, and Weber-Karyotakis 2018, 140.

158 Lichtenberger and Raja 2018a, 163; 2019a, 277–92.

159 Rattenborg and Blanke 2017, 319–24.

160 Blanke 2017.

161 Rasson-Seigne, Seigne, and Tholbecq 2018.

162 The collapse of the columns in the so-called Cathedral of Hippos is particularly striking; Wechsler and others 2018, 19, fig. 2.3.

By the Late Byzantine period, the city had experienced several major earthquake episodes, and the populace would have been well aware of their damaging effects. In the case of the Nymphaeum, the risk of further damage was mitigated by the construction of buttress walls on the northern and possibly also the southern elevations of the monument, and these walls are well preserved. Similar buttress walls were also built against the southern wall of the southernmost taberna across the laneway (the so-called Museum Street) to the north of the Nymphaeum, but such walls do not appear to have been common in the city.

The original Nymphaeum was a two-storey structure with a relatively slender profile that was built on the corner of the Cardo and Museum Street by AD 190-191 163. The lack of excavation to the rear of the Nymphaeum means that nothing is known of structures built against it on the west elevation, but, contrary to the findings of the Yale Mission, the Nymphaeum was not originally joined to second-century rooms to the south 164. The Nymphaeum's central semicircular facade was reasonably well protected against earthquake stress by thicker walls and flanking lateral projecting wings, but the lateral wings themselves had thinner walls that supported huge masonry pilasters and were less well protected. This exposure was later demonstrated by severe damage to upper storeys of both lateral wings above the level of the buttress walls yet much of the facade interior undamaged.

The evidence suggests that the buttress walls were built in two stages. In the first stage, a well-constructed spolia wall of hard limestone ashlars, including one block with a second-third-century inscription, was added to the northern elevation 165. In the second stage, a thicker, less well-constructed wall of large nari blocks was built against the earlier stage 1 wall of the Nymphaeum, and a similar wall was built against the original southern wall of the taberna on the north side of Museum Street (Figs 3.42a-3.42d). The importance of the work can be deduced by the fact that the second phase walls reduced the width of Museum Street from 5.3 m to 3.8 m. The wall abutting the original southern wall of the Nymphaeum may also have been built in the second stage (Figs 3.43a-3.43c). The timing of the building of the buttress walls is currently uncertain: it seems likely that the first support wall was added after a seismic event had impacted the city and demonstrated the damage risk to the monument, and on present evidence, it appears that the first strong earthquake impacts were in the fourth/fifth centuries. The inscribed blocks included in the wall as spolia provide a second/third-century terminus ante quem. Brenk, Bowden, and Martin suggested that the first stage wall on the northern elevation of the Nymphaeum was part of a reconstruction of the area west of the Nymphaeum carried out in the first half of the fifth century 166. From the available evidence, it is speculated that the building of the first and second phase buttress walls was triggered by damage to the Nymphaeum caused by the seismic events of the fourth/ fifth centuries.

163 See the description of the Nymphaeum (fountain 6) in

Appendix I.

164 Plans from the Yale Mission show that in the second

century the Nymphaeum was joined to 'Room 18' to the

south that formed part of the second-century propylaeum

of a temple that was later replaced by the Cathedral in

the mid-fifth century (Crowfoot 1938, 203, plan XXIX).

This presentation is misleading, as even a cursory field

examination shows that the northern wall of 'Room 18'

that abutted the southern wall of the Nymphaeum does not

date to the second century but is much later (probably

late Byzantine). This later wall abuts the west wall of

Room 18, which is probably second century, but does not

interleave with it. When built, the Nymphaeum was

separated from Room 18 by a horizontal distance of c. 1 m.

166 See Brenk, Bowden, and Martin 2009.

- from Boyer (2022:82-87)

The largest earth movements are landslides, and many were recorded in the study area during the geological mapping conducted by the Jordanian government, but they are more common than the mapping suggests.167 Seismically induced rock falls and topples can be found associated with most natural cliffs and escarpments throughout the study area, and especially along landslide back scarps. There are several examples where these falls have damaged bedrock agricultural installations (Figs 3.45a–3.45d), but aqueducts constructed close to the edge of escarpments were particularly affected by this form of seismic damage (Figs 3.46a–3.46e).

Some types of earth movement can be triggered by heavy rainfall as well as seismic events, but seismic events exacerbate the risk of landslides occurring in susceptible areas. The combination of steep slopes and unstable marl and clay units within the bedrock sequence has created a local landscape susceptible to earth movements. This particularly applies to areas underlain by the Upper Cretaceous Shueib Formation in the north-western part of the study area and on steep slopes adjacent to the wadi at lower elevations, especially in areas underlain by Lower Cretaceous Kurnub Formation sandstone. Recent landslide research in the vicinity of the Amman–Irbid highway classified much of the southern Jarash valley and the lower part of the Tannur valley in the vicinity of the highway as ‘highly susceptible’ to landslides (Fig. 3.47a), and significant sections of the wadis were classified as ‘very highly susceptible’ (Fig. 3.47b).168 The ‘very highly susceptible’ areas in the Jarash valley south of Shallal are underlain by Kurnub sandstone and have been rendered unstable by numerous small springs on steep slopes and the undercutting of banks by wadi erosion and road construction, but research has shown that the key landslide trigger-mechanism in the area since the mid-twentieth century has been heavy rainfall.169 Aerial images reveal evidence of many landslides that impacted directly on slopes and infrastructure beside the wadi and often on the course of the wadi itself.

The absolute dating of individual landslide events was not attempted in the study; however, the geological evidence suggests that landslides have been a feature since the earliest stages of landscape development and continue to occur today. Seismic events in Antiquity or possibly earlier are likely to have been the cause of a cluster of landslides over a distance of c. 1 km in the vicinity of the Der Abu Saedi locality, 3 km south of the city, that changed the course of the wadi (Fig. 3.48). Closer to the city, a well-preserved example of a translational landslide on the west bank of Wadi Jarash in the Bab Amman locality (hereafter, the Bab Amman landslide) involved the detachment of a c. 500 m long section of the eastern side of the Bab Amman mesa at site JWP147 and resulted in the dislocation of a group of rock-cut aqueducts supplied from Qwndeit spring (Figs 3.49a–3.49b). At least part of the backscarp of this landslide follows a line of weakness created by one of the aqueducts cut into the bedrock. The landslide has not been dated in absolute terms, but the weathering of the backscarp and lateral scarps, the rock falls along these scarps, and the existence of significant colluvial accumulations on top of the landslide is taken to be evidence that it probably dates to Antiquity.

An unusually well-preserved section through a debris flow in a historical landslide is visible in a cut in the south bank of Wadi Suf at site JWP194, west of Mukhayyam Suf (hereafter, the Wadi Suf landslide). The site lies at the foot of a forty-degree slope, and the flow may have originally engulfed the wadi bed at this point. An overview of the landscape setting is shown in Figures 3.50a–3.50b, and details of the profile through the boul dery front of the debris flow are shown in Figures 3.51a–3.51b. The debris flow was deposited on a seemingly undisturbed palaeosol. This sequence is currently undated, but evidence of a ‘rubble slide’ of Yarmoukian (Pottery Neolithic) date overlying PPN stratigraphy at Tell Abu Suwwan suggests that there is a long history of this type of deposition in the area.170

Not all landslides are the result of seismic activity. Studies of recent landslides that affected the Amman–Irbid highway in the southern Jarash valley highlighted the combined impact of heavy rainfall, especially heavy rainfall events that can result in swelling and instability in claystone layers, fractured bedrocks, high drainage density, and the undercutting of unstable slopes by road construction.171 An example of a rotational landslide is shown in Figure 3.52a, and a (?) translational landslide associated with a fault down the slope at Jarash Bridge is shown in Figure 3.52b.

166 See Brenk, Bowden, and Martin 2009.

167 Abdelhamid 1995.

168 Awawdeh, El Mughrabi, and Atallah 2018.

169 Farhan 1999.

170 See Weninger and others 2009, 30–33. The c. 1 m thick

Tell Abu Suwwan deposit was one of several examples

identified in Jordanian Neolithic sites.

171 See Awawdeh, El Mughrabi, and Atallah 2018. For a

discussion of the causes of landslides in Kurnub sandstone,

see also Malkawi and others 1998, 19.

- from Boyer (2020)

The key elements in the physical landscape are outlined, and differences in geology and climate that affected settlement and water use in two adjacent valleys are explained. The paper describes the relatively simple open channel aqueduct network and its spring sources, drawing comparisons with the more sophisticated tunnel aqueduct system that supplied the Decapolis cities of Abila, Capitolias and Gadara. The water management system intra muros is poorly understood, a reflection of the fragmentary exposure of a multilayered network spanning many centuries and the difficulty in discriminating between runoff and aqueduct sources in the relatively small areas of the city excavated to date. The water management system included a system of water storage both inside and outside the city. The largest known aqueduct-supplied reservoir in the city was located on a hilltop in the city's north-west quarter. It had a capacity of ca. 2200 m3 and was in use from the first to the sixth centuries AD. The largest reservoir in the study area is the 2nd century AD spring basin at Birketein. 1.6 km north of the city. Built in stages. this two compartment masonry reservoir became a large castellum divisiorum for an aqueduct system that distributed water to both urban and rural users. The structure had a volume of ca. 18,000 m3, but the elevation of the supply springs limited its effective storage capacity to around half of the available volume.

The area was affected by landslides and rapid sedimentation caused by intense rainfall events from the fourth century to the early seventh century, and this also impacted the water management system. There is evidence of seismic damage to aqueducts and water storage installations, and there are also examples of sections of aqueducts being lost in landslides. There is evidence of a reduction in the water supply to several fountains in the city that probably dates to the Byzantine period, but it is not presently known if this reflects a reduction in supply at the source or the redistribution of finite water resources in the face of increasing demand. The city suffered badly from various earthquake events between the fourth and eighth centuries, especially the dramatic AD 749 earthquake. The city recovered, however, and settlement continued at a reducing scale into the Islamic medieval period, but permanent settlement had ceased before the arrival of the first European visitors in the early 19th century.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Site JWP115

Figure 1

Figure 1

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated. Click on image to open in a new tab Passchier et al. (2021) |

Figs. 2.15a and 2.15b |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Site JWP115

Figure 1

Figure 1

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated. Click on image to open in a new tab Passchier et al. (2021) |

Figs. 2.15a and 2.15b |

|

|

Boyer, D. D. (2014) Aqueducts and Birkets: New Evidence of the WaterManagement System Servicing Gerasa (Jarash), Jordan

, Proceedings, 9th ICAANE, Basel 2014, Vol. 3, 517-531

Boyer, D. D. (2017) Jerash Water Project: report on the 2013 Field Season

, ADAJ 58, 375-412

Boyer, D. D. (2020a). The Aqueduct Systems Servicing Gerasa of the Decapolis

. In G. Wiplinger (Ed.), De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae: Sextus Julius Frontinus and the Water of Rome – Rome November 10-18, 2018,

ÖAI Sonderschrift/Babesch Annual Papers on Mediterranean Archaeology, Supplement 40 (pp. 175-186). Leuven: Peeters.

- at JSTOR

Boyer, D. D. (2020b). The Aqueduct Systems Servicing Gerasa of the Decapolis

. In G. Wiplinger (Ed.), De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae: Sextus Julius Frontinus and the Water of Rome – Rome November 10-18, 2018,

ÖAI Sonderschrift/Babesch Annual Papers on Mediterranean Archaeology, Supplement 40 (pp. 175-186). Leuven: Peeters.

- at academia.edu

Boyer, D. D. (2022) Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland: From the Romans to AD 750

, Brepols Publishers

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)