Teleilat Ghassul

Teleilat el-Ghassul

Teleilat el-Ghassulclick on image to open a slightly high res magnifiable image in a new tab

APAAME

APAAME_19980517_

RHB-0044.tif

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Teleilat Ghassul | Arabic | |

| Tuleilat el-Ghassul | Arabic | |

| Tulaylât al-Ghassûl | Arabic |

Tuleilat el-Ghassul is a large settlement (c. 50 a. in area) dating from the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. The site, c. 295 m below sea level, is made up of a group of small mounds and is situated in the lower Jordan Valley, about 5 km (3 mi.) northeast of the Dead Sea. The site was initially discovered in the 1920s, by A. Mallon and a team from the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Jerusalem. During this early phase of research, the investigators were primarily concerned with identifying the five cities of the plain mentioned in Genesis 14 and tentatively identified Ghassul with one of them. Following the first excavations, from 1929 to 1938, it became clear that Tuleilat el-Ghassul represented a new pre-Bronze Age culture in the country's archaeological history. The first to suggest ascribing this culture to the Chalcolithic period was W. F. Albright, and by the mid-1930s its distinct material culture made Tuleilat el-Ghassul the type site for this period.

The initial excavations by the Pontifical Biblical Institute revealed four major superimposed strata (I-IV, earliest to latest), separated from one another by layers of ash, wind-blown and other sediments. The maximum depth of the cultural deposits reached approximately 5 m. The most perplexing problem associated with these deep stratigraphic excavations was the lack of change observed in the material culture assemblage. This homogeneity led the researchers to interpret the four strata as representing a single culture, which R. Neuville named Ghassulian, a term that became synonymous with the Chalcolithic period in this country. To tackle the stratigraphic problem anew, the Pontifical Biblical Institute resumed excavations in 1960, under the direction of R. North, but was unsuccessful in demonstrating any technological development. In 1967, the third and most recent phase of excavation was initiated by B. Hennessy, under the aegis of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. These excavations (1967 and 1975-1978) focused on providing a reliable stratigraphy and sequence of settlement on the site's various mounds; stratigraphically relating the individual mounds to one another; obtaining a large exposure of the earliest settlement phase; collecting paleoenvironmental data; establishing an absolute chronology for the site, using radiocarbon methods; and relating the site to surrounding settlements assumed to be contemporary. Since the early excavations, numerous regional cultures dating to the Chalcolithic period have been found in Israel and Jordan, limiting the value of the term Ghassulian to the site and its immediate environs

Excavation of Ghassul (see Vol. 2, pp. 506–511) was renewed in the 1990s with three seasons conducted by a team from Sydney University (Australia) led by S. Bourke. The work consisted of several small soundings on some of the hillocks that make up the site. All remains date from the Chalcolithic period, but analysis of the finds is only in a preliminary stage. The limited nature of the soundings meant that large areas of coherent architecture were not uncovered. Rather, multiple phases (sometimes up to 10) of partial houses and courtyards with pits and silos were discerned. Aside from the usual tools and ceramics at the site, another small fragment of a painted wall fresco was found.

Tuleilat el-Ghassul is the largest Chalcolithic site in the country and provides new evidence concerning the local evolution of this culture beginning in the Late Neolithic period. Although previously viewed as the type site for the Chalcolithic, very few copper objects have been found at the site. No evidence of metal production was found in the recent excavations and only a few copper axes were recovered in the Pontifical Biblical Institute's investigations. Recent radiocarbon dates and the pottery from the earliest phase suggest an affinity to the Pottery Neolithic at Jericho, Middle and Late Neolithic Byblos, and Neolithic sites in the southern Beqa'a in Lebanon. While general similarities exist between Ghassul and the Beersheba Valley sites, the relationship between these cultures is more complex than previously thought. This is due to the lack of radiocarbon dates from the upper levels at Ghassul, the virtual absence of a metal industry at the site, and the need for more provenance studies to trace interregional relations during this period. Recent excavations at Gilat show that this site has more affinities with Ghassul. Although Tuleilat el-Ghassul has been investigated for over sixty years now, scholars have still not explained why it grew into one of the largest late fifth-to fourth-millennia sites in the Levant.

- Map 1 - Late Neolithic

Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 1

Map 1

Late Neolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001) - Map 2 - Early and Middle

Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 2

Map 2

Early and Middle Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001) - Map 3 - Late Chalcolithic

Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 3

Map 3

Late Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001) - Teleilat Ghassul in Google Earth

- Map 1 - Late Neolithic

Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 1

Map 1

Late Neolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001) - Map 2 - Early and Middle

Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 2

Map 2

Early and Middle Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001) - Map 3 - Late Chalcolithic

Sites of the Levant from Lovell (2001)

Map 3

Map 3

Late Chalcolithic Sites of the Levant

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 1.1

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul before excavation by PBI from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul made before excavation by PBI

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 11)

(NB The T numbers are tells, the S numbers are soundings made before major excavations)

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 1.1

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul before excavation by PBI from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul made before excavation by PBI

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 11)

(NB The T numbers are tells, the S numbers are soundings made before major excavations)

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

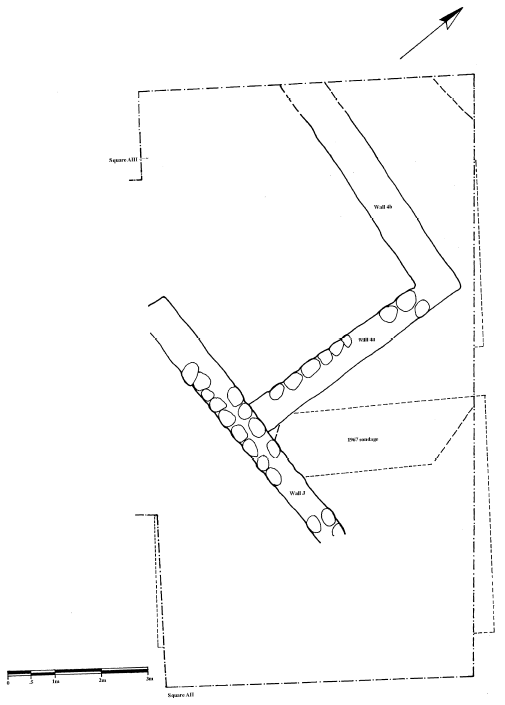

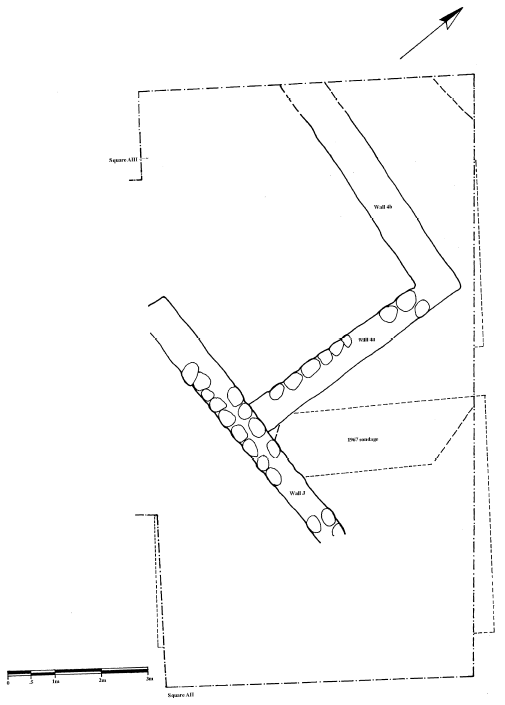

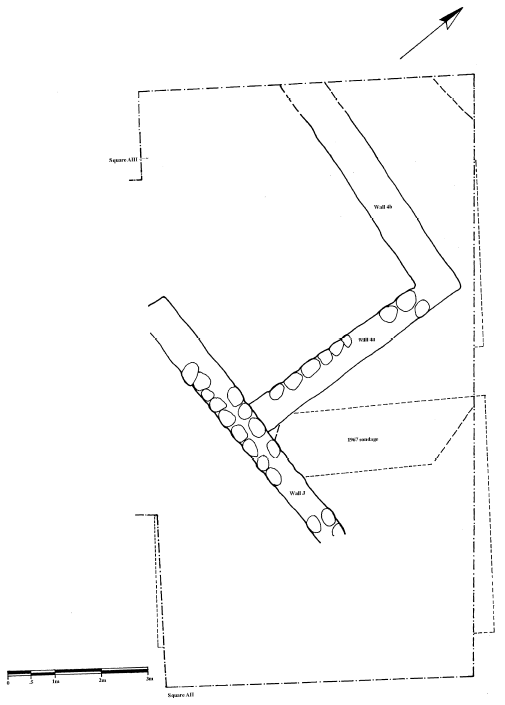

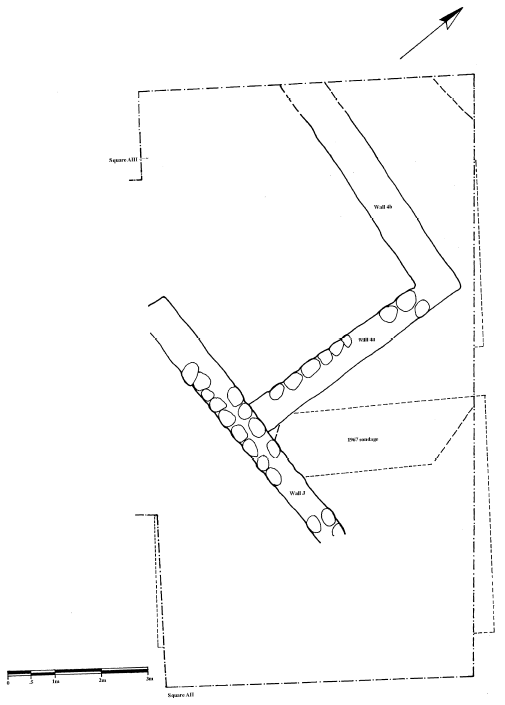

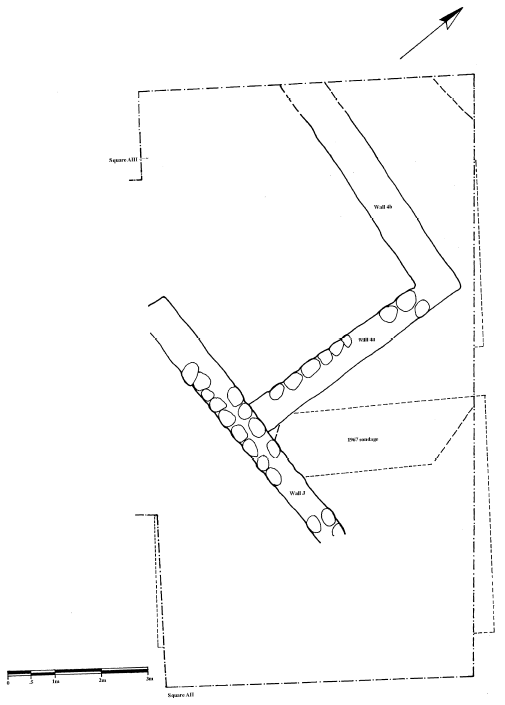

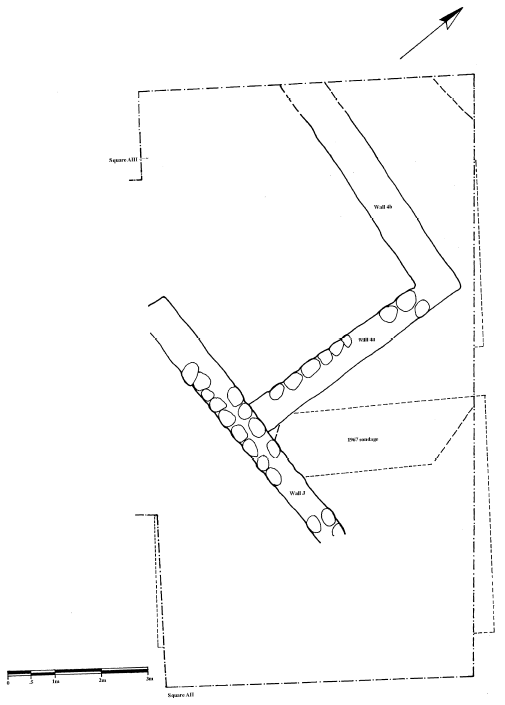

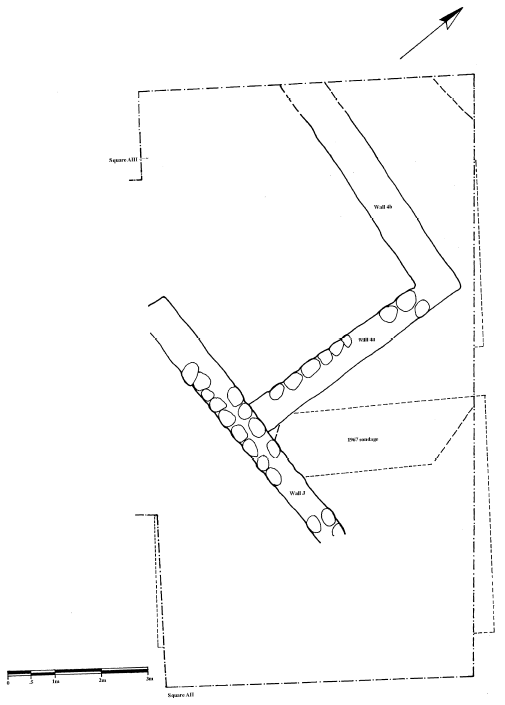

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A phase C from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.9

Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A, phase C

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A phase B from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.10

Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A, phase B

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A phase A from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.11

Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A, phase A

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A phase C from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.9

Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A, phase C

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A phase B from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.10

Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A, phase B

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A phase A from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.11

Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A, phase A

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1 from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 12)

Lovell (2001) -

Plan of stratum IV on mound I from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Tuleilat el-Ghassul: plan of stratum IV on mound I

Tuleilat el-Ghassul: plan of stratum IV on mound I

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1 from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 12)

Lovell (2001) -

Plan of stratum IV on mound I from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Tuleilat el-Ghassul: plan of stratum IV on mound I

Tuleilat el-Ghassul: plan of stratum IV on mound I

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Fig. 3.14

section AII from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.14

Fig. 3.14

Teleilat Ghassul 1967-77, section AII

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.13

AX Harris matrix from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.13

Fig. 3.13

AX Harris matrix

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.15

Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix

Lovell (2001)

- Plate III.1

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.1

Plate III.1

Teleilat Ghassul, aerial view taken in 1967

(Photo courtesy TG project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.2

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.2

Plate III.2

AXI sondage (at original 1x2m) directly west of original Alli square. Note that the original baulks were cut back significantly in 1994 for safety

(Photo JLL)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.9

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.9

Plate III.9

AII, phase H/1, post holes and fill

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.14

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.14

Plate III.14

AII, phase D, walls A', B', C', G'

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.15

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.15

Plate III.15

AII, phase D, looking west. Note also the mudbrick bench associated with wall A'

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.16

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.16

Plate III.16

AII, phase C walls J & K looking east.

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.17

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.17

Plate III.17

AII, phase C, walls J, K, L & M at end 1967, note area of sondage to north

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.18

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.18

Plate III.18

AII, phase A, wall 1 and Circular installation (Feature 8) looking west

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.19

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.19

Plate III.19

AII, phase A, walls F, G and H looking northwest, note cut for Burial 3 to the left of walls F and G

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.20

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.20

Plate III.20

AII, phase A, burial 4 looking north east

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.30

Fallen mudbricks AIII, phase E from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.30

Plate III.30

AIII, phase E, group of cornets and chisels amongst fallen mudbrick

(Photo courtesy TG project)

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1 from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 12)

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1 from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Plan of excavated house from Tell 1

(after Mallon et. al. 1934: fig. 12)

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001)

- Plate III.1

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.1

Plate III.1

Teleilat Ghassul, aerial view taken in 1967

(Photo courtesy TG project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.2

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.2

Plate III.2

AXI sondage (at original 1x2m) directly west of original Alli square. Note that the original baulks were cut back significantly in 1994 for safety

(Photo JLL)

Lovell (2001)

- from Lovell (2001:19)

The PBI excavators had an eye for certain aspects of detail, for example bricks were described at some length (Mallon et al. 1934:34-5) and their ground plans (an example is reproduced here as figure 1.2) suggested a degree of town planning. Impressive features were documented including streets (Koeppel 1940:pl. 18.2) and covered drains (Koeppel 1940:pl. 32.2). The two volumes present quite good photographs and plans that give detailed notes on installations of various kinds. They also go to some effort to explain the geographical setting of the site (Mallon et al. 1934:5-26). Nonetheless, they did not present complete catalogues of material13, nor were they able to document in publication the four-five stages they claimed to have excavated at the site. Koeppel made an attempt to divide level IV, the upper level, into two phases, IV A and IVB on stratigraphic grounds, but this is not successful:

We have come to the conclusion that all the walls and hearths can be divided into two classes that belong to levels IV A and B respectively, although we must admit that they really form one whole (Koeppel 1940:53).The joint British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and University of Sydney (BSAJ/USyd) work was more careful in its stratigraphic investigation and provided new insights. Hennessy's first season distinguished ten building phases and broad exposures revealed carefully excavated floor deposits which tell us much more about the daily activities of the site's inhabitants. It was noted that earthquake faulting had disrupted stratigraphy so that some areas were not able to be effectively investigated.

There is still significant academic interest in the sequence at Teleilat Ghassul, especially in the "pre-Ghassulian" levels. Despite a number of preliminary reports (Hennessy 1969, 1982, 1989), Hennessy's work was not completely accepted at the time. His Late Neolithic material remains largely unpublished and there is still significant interest in the sequence. The BSAJ/USyd team excavated Late Neolithic material over c. 46 m2. Bourke's excavations have increased the coverage to c. 51 m2 in total. This book publishes the critical Area A ceramic sequence from both Hennessy and Bourke's excavations.

Material excavated over a 30 year period is included in this study. It begins with material excavated by E. Prof. J.B. Hennessy's project (1967-77) and is supplemented by material excavated by Dr S. J. Bourke's team (1994- 7). The following chapter presents the stratigraphic context of the ceramics considered in this book, which concentrates primarily upon the material from Area A ( the deep cut). This is because it is the only area where a complete sequence is present. No other area on the site has produced Late Neolithic material. This area is arguably the most intensively explored area on the site, although the area where the "sanctuary complex" was found (Area E) has also been well sounded.

13 A catalogue of the ceramics and other finds was later attempted by Lee (1973) although this has remained unsatisfactory due to the lack of firm stratigraphy.

- from Lovell (2001:19-20)

On the basis of his excavations Hennessy stated that he had isolated ten phases of occupation, A+ to I (Hennessy 1969). These effectively break down into four main phases of occupation, which I have termed Late Neolithic, Early Chalcolithic, Middle Chalcolithic and Late Chalcolithic (table 3.1). It must be stressed that it is not clear how these might relate to the original PBI determination of I-IV, which was based on crudely excavated information. It is shown in table 3.1 that Bourke's sondages include an extra phase (phase J) which predates the BSAJ/USyd's earliest phase (I). The BSAJ/USyd "pit-dwellings" were dug into sterile soil whereas Bourke's were dug into occupation levels that were largely without features (phase J). It is difficult to be definitive about the reason for this given the small exposures thus far revealed by the USyd team. Sterile was reached in the AX and AXI sondages at a lower absolute level than that of Hennessy's. It may be assumed that Bourke's sondages are, in fact, on the western-most edge of the Late Neolithic tell, and perhaps a little downslope from Hennessy's. In this case, phase J may not be significantly different from Hennessy's phases H and I, and for the purposes of this research, they are treated together.

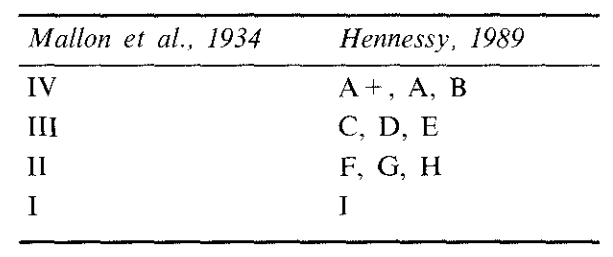

Table 3.1 gives the stratigraphic phases as isolated in Hennessy's and Bourke's excavations. It should be noted that phases A+ to I, as they are interpreted here, may not correspond exactly to Hennessy's original divisions.

Table 3.1

Table 3.1Correlation between BSAJ/USyd and USyd work

Lowell (2001)

Hennessy's first stratigraphic analysis was based solely upon the 1967 All sondage (Hennessy 1969). Detailed description of his stratigraphic divisions of deposits excavated after 1967 has never appeared in print. The stratigraphic analysis which appears here is my own interpretation of the two squares as a whole, and as they compare to Bourke's sondages. Correspondence between the two excavations was made largely on the basis of the sections and plans, taking into account similar features and absolute levels. The close proximity of Bourke's sondages to Hennessy's material made this relatively easy. The periodisation here is based upon major phase groupings. These rely upon the major changes in building phases (see below).

- from Lovell (2001:20)

- from Lovell (2001:20)

- from Lovell (2001:20)

14 Almost all of the non-registered finds from the 1994-7 excavations are held in store at the University of Sydney, N.S.W. Australia. Material from the Hennessy excavations is split between Sydney (which has the large bulk of material), the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem (BSAJ), the British Museum (BM), the Nicholson Museum, Sydney, the Amman Citadel Museum and the Salt Museum, Jordan. Registered small finds from the 1994-1997 seasons were divided 70:30 to Jordan.

- from Lovell (2001)

Table 6.1

Table 6.1A Proposed Relative and Absolute Chronology for the Teleilat Ghassul Sequence

Lovell (2001)

Through the various years of excavation, an area of over 10,500 sq m was exposed. Although the earlier excavators defined four main phases, the precision of Hennessy's more recent excavations defined ten major building phases separated by camp-floor occupations. The latter occurrences are interpreted as occupational subphases when the site was reconstructed for resettlement following periods of destruction. The entire sequence, labeled phases A through I, contains over one hundred successive floor levels. Although there is a paucity of reports concerning the recent excavations, the preliminary studies show technological development for the pottery and, to a limited extent, for the flint industries. The recent excavations also suggest that frequent seismic activity in the Jordan Valley caused the destruction of numerous settlements found in the archaeological sequence. Hennessy's excavations show no continuity for the Chalcolithic settlement into the subsequent Early Bronze Age, but there is a degree of continuity from the Late (Pottery) Neolithic period not noted by the original excavators. The following table equates the original four major phases (I-IV) with Hennessy's:

Table equating the original four major phases (I-IV) with Hennessy's

Table equating the original four major phases (I-IV) with Hennessy'sStern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A phase C from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.9

Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A, phase C

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A phase C from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.9

Fig. 3.9

Composite plan of Area A, phase C

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.14

section AII from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.14

Fig. 3.14

Teleilat Ghassul 1967-77, section AII

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.15

Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix

Lovell (2001)

- Plate III.16

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.16

Plate III.16

AII, phase C walls J & K looking east.

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.17

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.17

Plate III.17

AII, phase C, walls J, K, L & M at end 1967, note area of sondage to north

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001)

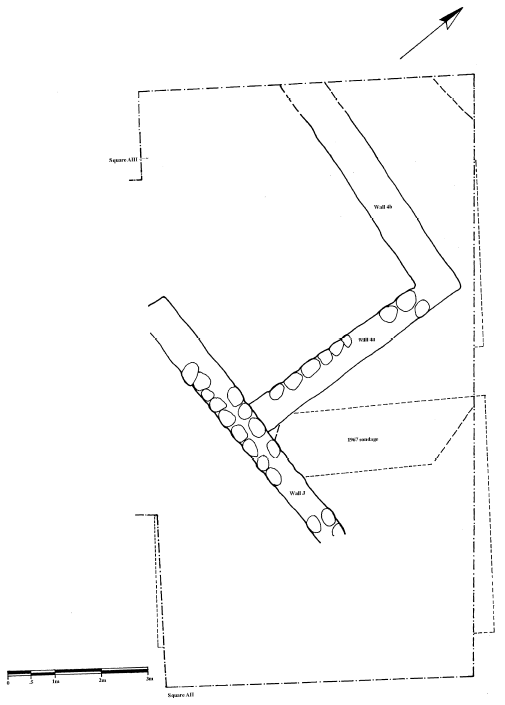

Lovell (2001:25) identified

a number of earthquake splits [fissures in the floor]in an area that

was probably the entranceto a structure whose corner is manifest in walls J and K. See Fig. 3.9 for the plan and Plates III.16 and III.17 for photos.

- from Lovell (2001:24)

23 This means that when the present author began work, a large amount of pottery had to set aside because it was not clear to which phase it belonged. This problem has only affected the ceramics from AII.

- from Lovell (2001:25)

A floor covering the entire room was excavated as 106.17 and runs up to wall J. Two door sockets were found in debris in a level above which may indicate that in this earlier phase the door was in another position.

The removal of 107.11 and 11a-c revealed the existence of a new structure formed by walls L and M. The area between these two walls was not excavated in 1967. The area outside the structure was excavated in a sounding beside the north section (107.12-16). A sub-phase is present in the form of wall N and its associated deposit (107.17). From the photograph (plate III.17) walls M and K appear to be bonded together. A third wall appears in 1975 plans. This is not numbered, but significantly changes the nature of the structure (see figure 3.9).

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A phase B from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.10

Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A, phase B

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A phase B from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.10

Fig. 3.10

Composite plan of Area A, phase B

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.14

section AII from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.14

Fig. 3.14

Teleilat Ghassul 1967-77, section AII

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.13

AX Harris matrix from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.13

Fig. 3.13

AX Harris matrix

Lovell (2001)

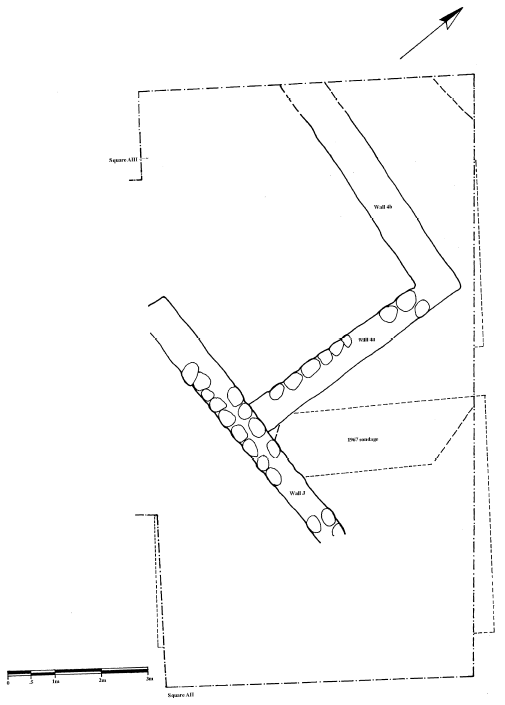

Lovell (2001:26) identified

an earthquake/subsidence split [fissure]on the interior of Wall 4b. See Fig. 3.10 for the plan.

- from Lovell (2001:25)

- from Lovell (2001:26)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A phase A from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.11

Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A, phase A

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1a

Fig. 3.1a

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul showing excavated areas

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.1b

Fig. 3.1b

Plan of Teleilat Ghassul, Area A showing the position of Bourke's soundings

Lovell (2001) - Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A phase A from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.11

Fig. 3.11

Composite plan of Area A, phase A

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.14

section AII from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.14

Fig. 3.14

Teleilat Ghassul 1967-77, section AII

Lovell (2001)

- Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix from Lovell (2001)

Fig. 3.15

Fig. 3.15

AII Harris matrix

Lovell (2001)

- Plate III.18

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.18

Plate III.18

AII, phase A, wall 1 and Circular installation (Feature 8) looking west

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.19

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.19

Plate III.19

AII, phase A, walls F, G and H looking northwest, note cut for Burial 3 to the left of walls F and G

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001) - Plate III.20

from Lovell (2001)

Plate III.20

Plate III.20

AII, phase A, burial 4 looking north east

(Photo TG Project)

Lovell (2001)

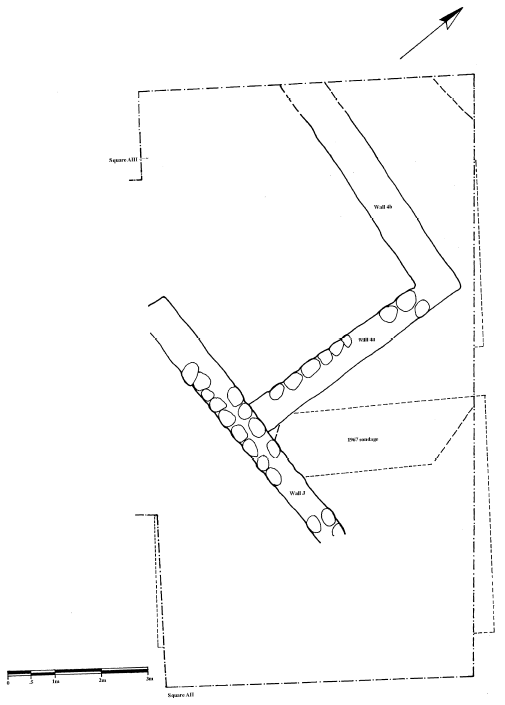

Lovell (2001:25) reports that

The area under walls G and F (phase A) is earthquake disturbed. He also shows apparent earthquake fissures on a nearby floor. See Fig. 3.11 for the plan. A radiocarbon date was obtained from a sample taken from a posthole under wall I with the context number AII 107.3/4 ( Lovell, 2001:25 n. 25). Weinstein (1984:334) supplied the following results from radiocarbon dating of this sample.

| Provenance | Material | 14C date BP | 14C date BCE | CRD-1σ date | Lab no. | Refs and Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teleilat el- Ghassul Area AII p.107.3 and 4 |

Wood | 6430 ± 180 | 4480 | 5540-5195 BCE | SUA-736 | Unpub; pers commun, J B Hennessy |

- from Lovell (2001:24)

23 This means that when the present author began work, a large amount of pottery had to set aside because it was not clear to which phase it belonged. This problem has only affected the ceramics from AII.

- from Lovell (2001:25)

Locus 106 is the levels within walls E and F. These levels are 106.1 and 1a (mud brick debris), 106.2 (silty ash) and 106.3 (wash with mud brick debris). In the comer of this structure were burials 4 (plate III.20) and 5, two infant burials with a broken pot covering each and associated flints. These were excavated together as 106.3a (see plate III.19 for their location). Locus 103 also belongs to this phase.

In addition, the removal of the floor 107.3 revealed another floor level (107.4) which ran up to a new wall (wall I)25. Levels under this included 107.5-7. The area under walls G and F (phase A) is earthquake disturbed. This was excavated as 106.8-12. Locus 108 belongs to this phase also.

25 A radiocarbon date was calculated from a sample (SUA 736) taken from a posthole with the context number AII 107.3/4 (Weinstein 1984:334) . This posthole is visible in the section. See chapter 5 for further details.

| Damage Type | Location | Image(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractures folds and popups on irregular pavements ? |

entrance to a structure outside the corner of walls J and K

Fig. 3.9

Fig. 3.9Composite plan of Area A, phase C Lovell (2001) |

Plate III.16

Plate III.16AII, phase C walls J & K looking east. (Photo TG Project) Lovell (2001)

Plate III.17

Plate III.17AII, phase C, walls J, K, L & M at end 1967, note area of sondage to north (Photo TG Project) Lovell (2001) |

|

| Damage Type | Location | Image(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Wall ? | inside of wall 4b

Fig. 3.10

Fig. 3.10Composite plan of Area A, phase B Lovell (2001) |

|

| Damage Type | Location | Image(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractures folds and popups on irregular pavements ? |

area under walls G and F

Fig. 3.11

Fig. 3.11Composite plan of Area A, phase A Lovell (2001) |

|

A. Mallon and R. Koppel, annual excavation reports, in Biblica (!930-1938)

id. et al.,

Teleilat Ghassull, Rome 1934

Ghassul2, Rome 1940

R. North, Ghassul1960 Excavation Report, Rome

1961

R. North, Biblica40 (1959), 541-555

id., ADAJS-9 (1964), 68-74

id., SHAJ l (1982), 59-

66

B. Hennessy, RB 75 (!968), 247-250

id., Levant l (1969), 1-24

id., SHAJ I (1982), 55-58

E. D.

Stockton, Levant 3 (1971), 80-81

J. R. Lee, "Chalcolithic Ghassul" (Ph.D. diss., Hebrew Univ. of

Jerusalem 1973)

C. Elliott, PEQ 109 (1977), 3-25

id., Levant 10 (1978), 37-54;1. A. Sauer, BA 42(1979),

9

P.M. Schwartzbaum et al., Third International Symposium on Mudbrick (Adobe) Preservation, Ankara

1980, 177-200

D. 0. Cameron, The Ghassulian Wall Paintings, London 1981

American Archaeology in

the Mideast, 150

G. Dollfus, MdB 46 (1986), 5-6

T. E. Levy, BA 49 (1986), 82-108

id. and A. Holl,

Archeologie Europeenne 29 (1988), 283-316

I. Gilead, Journal of World Prehistory 2 (1988), 397-443

id.

(andY. Goren). RASOR 275 (1989), 5-14

Khouri, Antiquities, Amman 1988, 81-85

Weippert 1988

(Ortsregister)

Akkadica Supplementum 7-8 (1989), 230-241

Y. Goren, Mitekufat Ha'even 23 (1990),

100*-112*

B. Rothenberg, University of London. Institute for Archaeo-Metallurgical Studies Newsletter

17 (1991), 1-7.

Teleilat Ghassul Project, Sydney University: Ghassul Archaeozoological Report 1995–

1997 Seasons, by L. D. Mairs, 1997

Teleilat Ghassul Petrography 1995–1996, by W. I. Edwards, 1997;

Teleilat Ghassul Shell 1994–1997, A First Listing, by D. S. Reese, 1997

Ghassul Archaeobotany Report,

1997 Season, by J. Meadows, 1998

Teleilat Ghassul: A Large Village on the Periphery of Egyptian Trade,

by J. L. Lovell, 1998

S. A. Scham, Pastoralism and the Emergence of Sociopolitical Complexity in the

Chalcolithic Period, Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan (Ph.D. diss.), Washington, DC 1999

J. L. Lovell, The Late

Neolithic and Chalcolithic Periods in the Southern Levant: New Data from the Site of Teleilat Ghassul,

Jordan (Monographs of the Sydney University Teleilat Ghassul Project 1

BAR/IS 974), Oxford 2001

ibid.

(Reviews) Paléorient 28/2 (2002), 148–155. — BASOR 331 (2003), 69–71. — Mitekufat Ha’even 33 (2003),

218–224

JNES 64 (2005), 143–144. — NEAS Bulletin 50 (2005), 61–62.

B. Rothenberg, IAMS Studies 17 (1991), 6–7

S. Sadeh & R. Gophna, Mitekufat Ha’even 24 (1991),

135–148

J. B. Hennessy, ABD, 2, New York 1992, 1003–1006

id., OEANE, 5, New York 1997, 161–163;

J. Perrot, EI 23 (1994), 100*–111*

S. J. Bourke (et al.), ADAJ 39 (1995), 31–63

44 (2000), 37–91

id., AJA

99 (1995), 509–510

100 (1996), 518–520

103 (1999), 493–494

id., Orient Express 1996, 41–43

2000,

52–54

id., The Prehistory of Jordan II, Berlin 1997, 395–418

id., SHAJ 6 (1997), 249–260

id. Radiocarbon 43 (2001), 1217–1222 (et al.)

46 (2004), 315–323 (et al.)

id., Egypt and the Levant, London 2002,

152–164

id., PEQ 134 (2002), 2–27

id., Paléorient 30/1 (2004), 179–182

D. O. Cameron, Bolletino del

Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici 28 (1995), 114–120

P. L. Seaton, Trade, Contact and the Movement of

Peoples in the Eastern Mediterranean (J. B. Hennessy Fest.

Mediterranean Archaeology Suppl. 3

eds. S.

J. Bourke & J. -P. Descoeudres), Sydney 1995, 27–30

S. Scham, ACOR Newsletter 8/1 (1996), 4

id., AJA

101 (1997), 507–508

id., BA 60 (1997), 108

id., Dept. of Pottery Technology, Leiden University, Newsletter

16–17 (1998–1999), 85–105

id. (& Y. Garfinkel), BASOR 319 (2000), 1–5

A. Enea, Contributi e Materiali

di Archeologia Orientale 7 (1997), 163–176

L. Quintero & I. Kohler-Rollefson, The Prehistory of Jordan II,

Berlin 1997, 567–574

G. O. Rollefson, ibid., 567–574

A. Von den Driesch, ibid., 511–556

R. G. Khouri,

Jordan Antiquity Annual, Amman 1997–1998, no. 13

E. B. Banning, NEA 61 (1998), 188–237

66 (2003),

4–21

id., ICAANE, 1, Roma 2000, 1503–1514

J. L. Lovell, PEQ 130 (1998), 176

id., Australians Uncovering Ancient Jordan: 50 Years of Middle Eastern Archaeology (ed. A. Walmsley), Sydney 2001, 31–42;

M. Blackham, Levant 31 (1999), 19–64

Y. Garfinkel, Neolithic and Chalcolithic Pottery of the Southern

Levant, Jerusalem 1999

G. Philip & O. Williams-Thorpe, ICAANE, 1, Roma 2000, 1383

S. P. Tutundzic,

Glasnik: The Journal of the Serbian Archaeological Society 17 (2001), 77–88

I. Gilead, Beer Sheva 15

(2002), 103–128

A. H. Joffe, AASOR 58 (2003), 45–67.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |