Nessana

Aerial view of Nessana

Aerial view of Nessanaclick on image to open a magnifiable image in a new tab

Etan J. Tal - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 4.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Nessana | Greek | Νεσσανα |

| Nitzana | Hebrew | ניצנה |

| Nizzana | Hebrew | ניצנה |

| Auja el-Hafir | Arabic | عوجة الحفير |

| el-Audja | Arabic variant | يلأودجا |

| 'Uja al-Hafeer | Arabic variant | 'وجا الءهافيير |

| el Hafir | Arabic variant | يل هافير |

Nessana was located along the Incense Road and was settled from the Hellenistic to Early Arab periods (Avraham Negev in Stern et al, 1993). There is a Neolithic site in the vicinity. The Nessana papyri was discovered at Nessana.

Nessana is in the western part of the central Negev desert, 52 km (32 mi.) southwest of Beersheba (map reference 0970.0318). The settlement was in existence from the Hellenistic to the Early Arab periods. In 1807, U. J. Seetzen recorded the Arabic name 'Auja el-Hafir for the site on his travel map. E. Robinson discovered Nessana in 1838, but mistakenly identified it with 'Abda (q.v. Oboda). This mistake was corrected by E. H. Palmer in 1871.

Nessana seems to belong to the initial Nabatean wave of colonization in the Negev, at which time Elusa and Oboda were also founded. This is evidenced by the numerous imported Hellenistic wares found on the eastern side of the acropolis. Among these are second- and first-century BCE stamped amphora handles that originated in Rhodes, Cos, Pamphylia(?), and Italy. The early coins include those of Ptolemy IV (212 BCE), Ptolemy VIII (127-126 BCE), and John Hyrcanus (134-104 BCE). The Colt expedition assigned a fort (25 by 27m) on the eastern side of the acropolis to this period. Excavations made by the Ben-Gurion University team have shown that the monumental stairway leading from the lower city to the acropolis is not from the Byzantine period, as the Colt expedition assumed, but from the second half of the first century BCE. This writer believes that these stairs do not lead to a fort, but to a Nabatean temple.

The Middle Nabatean period (30 BCE-50/70 CE) is dated by painted Nabatean ware and Early Roman pottery, as well as by coins of Aretas IV (9 BCE-40 CE) and of Malichus (40-70 cE) or Rabbel II (70-106 CE). It seems that at this time a temple (?) was built on the eastern side of the acropolis. No finds could be dated to the Late Nabatean period. However, two coins of Septimius Severus (193-211 CE) suggest the possibility that Nessana was to some extent also inhabited in the Late Nabatean period. Activities on a very large scale began after the middle of the third century CE, and especially during the reign of Constantine II (312-337 CE). Nabatean ostraca, inscribed on pebbles with ink, may belong to the second and third centuries CE. The excavators did not date any buildings on the acropolis to this period, but ascribed the construction of the fortress to the early fifth century. On the other hand, Negev dates the large citadel to the early fourth century CE.

Shortly after the construction of the fortress on the acropolis, the North Church, which adjoins it, was built. At about the beginning of the seventh century, the South Church was built a short distance south of the citadel. There were two or three churches in the lower city, probably built in the fifth and sixth centuries, one of them excavated by the Ben-Gurion University team.

Nessana's prosperity continued throughout the Byzantine period and during the first century following the Arab conquest. To this period belong typical pottery vessels, Byzantine coins of Constans II (641-668 CE), and Arab coins imitating coins of that emperor, minted at Damascus, and in other Early Arab mints. The papyri found at Nessana, both Greek and bilingual Greek-Arabic, date from the sixth to late seventh centuries CE. There is no evidence for the existence of Nessana later than the eighth century CE.

The most significant discovery made at Nessana is literary, theological, and legal papyri. Among the literary papyri found by the Colt expedition were eleven books or fragments ofbooks: a Greek dictionary to Virgil's Aeneas; a fragment of Aeneas; several chapters of the Gospel of John; the Acts of Saint George; and the apocryphal letters of Abgar to Christ and Christ's reply. The 195 nonliterary documents and fragments date to 512 to 689 CE. Among them are documents relating to all spheres of life: financial contracts, marriage and divorce, division of property and inheritance, bills of sale, receipts of various kinds, letters concerning church matters, military matters, grain yields, and wheat. Bilingual Greek-Arabic documents are concerned with the requisition of wheat, oil and money, and food and poll taxes. Not all the papyri pertain to the central Negev region, however. Two lengthy documents dealing with the sale of dates must have come from the southern coastal region. Among the military documents are some their publisher explains refer to an account of the allotment of taxes by villages. In this papyrus, four sites in the central Negev, two in the Beersheba Plain, and three in the region to the north of the plain are listed. The editor suggested that the high sums of money named were taxes on landed property, to be paid by well-to-do farmers and land-owning soldiers (limitanei). This is, however, unlikely. According to the list, Nessana, Oboda, and Mampsis (Kurnub) are supposedly required to pay the same taxes; however, they differ greatly in both actual amount of landed property and population. This writer has suggested that the sums mentioned in the document are, rather, bimonthly payments of the annona militaris, which the military provincial authorities paid members of the militia recruited from the nine sites mentioned in the document. In one of the documents, in which much smaller sums of money are dealt with, payments to individuals or small groups of individuals are listed.

Palmer observed the remains of a church in the lower city, which according to him was in a very ruinous state, and drew a plan of the South Church on the acropolis, whose walls were still 9 m high. The walls of both the citadel and the church were still faced with ashlars. Along the riverbed of Nahal Nessana, Palmer marked the presence of three ancient wells, one of which was named by the local Bedouin Bir es-Saqiyeh (Well of the Water Wheel). A. Musil visited the site in 1902. He drew the first detailed plan of the lower city, a plan of the South Church on the acropolis, and a section of a well that the Turkish authorities cleared to a depth of 15 m without reaching the water level. E. Huntington, who visited 'Auja in 1909, described the administrative center the Turks had built in 1908 above the ruins of a church. The church had been decorated with multicolored mosaic pavements in which there were Greek inscriptions - one from the year 601 CE. He also mentioned another church, with inscriptions dating to the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries (there was a guest house on the ruins of this church). Huntington described two parallel colonnaded streets 200 m long. In the lower city, he observed remains of two additional churches. His description of the lower city is not supported by the description of any other travelers, however - including C.L. Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, who visited the site in 1914. By that time the Turks had already built three new buildings in the lower city.

In 1916, 'Auja was visited by the Committee for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments attached to the German-Turkish military command, under the direction of T. Wiegand. The new buildings were fully documented and a plan of the North Church on the acropolis, discovered then, was made. Several Greek inscriptions were copied, and the first papyrus fragments were found (see below). Nabatean painted pottery was identified as Coptic. In 1921, A. Alt published the 150 Greek inscriptions from the Negev known up to that time in the committee's publications. In 1933, J. H. Iliffe identified Nabatean painted pottery at 'Auja. The Colt expedition, under the auspices of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, excavated the site in 1935- 1936 and 1936-1937. Excavations were made on the acropolis, where the papyri were found in which the ancient name of the site, Νεσσανα, is frequently mentioned. In 1987, excavations at Nessana were resumed by the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, under the direction of D. Urman.

Excavations at Nessana in the Negev were resumed in 1987–1995 by an expedition of Ben-Gurion University, under the direction of D. Urman. In 1987–1991 the excavations were co-directed by J. Shereshevski, and in 1991–1992 by D. E. Groh.

- Location Map from

BibleWalks.com

Map of the ancient cities along the Incense/Spice route

Map of the ancient cities along the Incense/Spice route

based on BibleMapper 3.0

click on image to open in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

- Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

from BibleWalks.com

Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

click on image to open in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 2 Aerial View of Areas

AA, BB, and CC from Tchekhanovets (2023)

- Aerial view of Churches of

St. Sergius and Bacchus from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Nessana in Google Earth

- Nessana on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

from BibleWalks.com

Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

Annotated Aerial View of Nessana

click on image to open in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 2 Aerial View of Areas

AA, BB, and CC from Tchekhanovets (2023)

- Aerial view of Churches of

St. Sergius and Bacchus from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Nessana in Google Earth

- Nessana on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 3 survey Maps of ancient

Nessana from Tchekhanovets (2024)

- Fig. 3 survey Maps of ancient

Nessana from Tchekhanovets (2024)

- Site plan from

the Byzantine period from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

- Site plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Site plan from

the Byzantine period from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

- Site plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Byzantine Fort (Area G) from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Reconstruction of the northern monastery

from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Reconstruction of the

“Central” Church complex (area F) from Stern et. al. (2008)

- Fig. 2 Aerial View of Areas

AA, BB, and CC from Tchekhanovets (2023)

- Fig. 2 Aerial View of Areas

AA, BB, and CC from Tchekhanovets (2023)

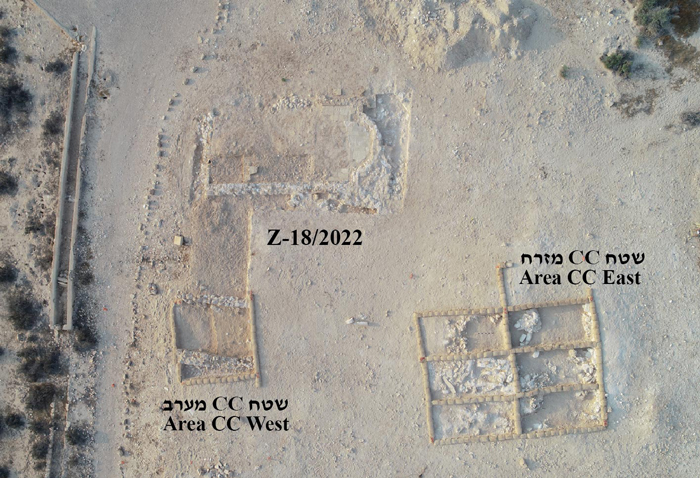

- Fig. 7 Aerial View of Area

CC from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 8 Aerial View of Area

CC West from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 9 Aerial View of Area

CC East from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 10 Oblique View of Area

CC East from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 7 Aerial View of Area

CC from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 8 Aerial View of Area

CC West from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 9 Aerial View of Area

CC East from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

- Fig. 10 Oblique View of Area

CC East from Tchekhanovets et al. (2024)

Excavation in this area focused on further exposing a church complex that had been partly unearthed during a salvage excavation earlier in 2022 (License No. Z-18/2022). Two excavation squares were opened, one located directly to the south of the church’s chapel (Area CC West) exposed during the salvage excavation, and the other was opened southeast of the chapel (Area CC East). The exposed remains and small finds are part of the previously unearthed church complex. All the remains should be attributed to Stratum II, as no Ottoman remains were documented.

In Area CC West (Fig. 8), two parallel walls were exposed with a sequence of living surfaces and abandonment layers of loess between them, dated based on the ceramic finds from the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods. The earliest floor was made of beaten earth and incorporated a tabun; the latest floor was paved with local limestone and imported marble slabs. The western side of the exposed space seems to have suffered damage by nearby Nahal ʻEzuz already in antiquity, and recently by modern development work at the site. Remains of water pipes and tubuli were discovered in this area, indicating the presence of a nearby bathhouse.

In Area CC East, an impressive low-lying mound resulting from the collapse of a building from the late Byzantine–Early Islamic periods was discovered (Fig. 9). The collapsed remains comprised building material, including light chalkstones, the stones of a collapsed vault arch, hard limestone slabs that were part of the ceiling of a second floor, wooden beams and plaster fragments. In addition, this accumulation yielded Byzantine and Umayyad ceramic finds, several well-preserved organic fragments—among these ropes and textiles—two Byzantine folles dated to the early sixth century CE and various botanical remains. A space divided by stone-built walls into four rooms, which were partly excavated (Fig. 10), was exposed below the collapsed material; no floor levels were reached here during the current season.

Erickson-Gini (personal correspondence, 2021) relates that Nessana suffered seismic damage in the 7th century CE - sometime after 620 CE.

Stroumsa R. (2008) “People and Identities in Nessana”. PhD Dissertation, Duke University. - open access

Tchekhanovets, Y, Rasiuk, A., Levy, A., and Peretz, A. (2024) Nizzana 2022.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 136.

Tchekhanovets, Yana (2023) The Perspectives Of Nessana: New Studies Of The “Caravan City” In Southern Israel

Rossiiskaia arkheologiia April 2023 (in Russian) - open access

Tchekhanovets Y. (2024) Excavating ancient pilgrimage at Nessana, Negev

. Antiquity. 2024;98(401):e29. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.132 - open access

Tepper Y., Weissbrod L., Erickson-Gini T., and Bar-Oz G. (2020) Nizzana 2017.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 132.

Tepper Y., Weissbrod L., Erickson-Gini T., and Bar-Oz G. (2020) Nizzana 2019.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 132.

Colt, H.D. et al. (1962) Excavations at Nessana 1, London

L. Casson and E. L. Hettich (1950) Excavations at Nessana 2: Literary Papyri, Princeton

C. J. Kraemer (1958) Excavations at Nessana 3: NonLiterary Papyri, Princeton - can be borrowed with a free account from archive.org

Urman, D. (2004) Nessana: Excavations and Studies. Israel: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Press.

D. Urman et al., Nessana Excavations 1987–1995 (Nessana Excavations and Studies 1; Beer Sheva 17), Beer-Sheva 2004 (Heb.)

Nessana Expedition Website

Nessana Expedition Website - Publications

Crisis on the margins of the Byzantine Empire website - run by Guy Bar-Oz at the University of Haifa

Nessana at BibleWalks.com

Yana Tchekhanovets at ResearchGate

- links to online versions of some of these are at the Nessana Expedition Website

Casson L. and Hettich E.L. 1950. Excavations at Nessana 2: Literary Papyri. Princeton.

Kraemer C.J. 1958. Excavations at Nessana 3: Non-Literary Papyri. Princeton.

Urman D. 2004. Nessana: Excavations and Studies (Beer-Sheva XVII). Beer Sheva.

Tepper Y., Weissbrod L., Erickson-Gini T., and Bar-Oz G. 2020. Nizzana 2017. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 132.

Tepper Y., Weissbrod L., Erickson-Gini T., and Bar-Oz G. 2020. Nizzana 2019. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 132.

Tchekhanovets Y. 2022. Nessana 2022. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 134 (forthcoming).

- links to online versions of some of these are at the Nessana Expedition Website

Ruffini G. 2011. Village Life and Family Power in Late Antique Nessana. Transactions of the American Philological Association 141/1: 201-225.

Hoyland R. 2015. The Protection (Dhimma) of God and Muhammad in Early Islam: P. Nessana 77 Re-discovered. In: B. Sadeghi, A. Ahmed, A. Silverstein and R. Hoyland (eds.), Islamic Cultures, Islamic Contexts: Essays in Honor of Professor Patricia Crone. Leiden and Boston. Pp. 51-71.

Hoyland R. 2021. P. Nessana 56: A Greek-Arabic Contract from the Early Islamic Palestine and its Context. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 51: 133-148.

Hoyland R. 2021. The Arabic Papyri from Early Islamic Nessana. Israel Exploration Journal 71/2: 224-241.

Pogorelsky O., Stone M.E. and Tchekhanovets Y. 2019. Armenians in the Negev: Evidence from Nessana. Le Muséon 132/1-2: 123-137.

Bar-Oz G. et al. 2019. Ancient Trash Mounds Unravel Urban Collapse a Century before the End of Byzantine Hegemony in the Southern Levant. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences.

Marom N. et al. 2019. Zooarchaeology and the Social and Economic Upheavals of Late Antique – Early Islamic Sequence of the Negev Desert. Nature Scientific Reports.

Fuks D. et al. 2021. The Rise and Fall of Viticulture in the Late Antique Negev Highlands Reconstructed from Archaeobotanical and Ceramic Data. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences.

Betzer P. 2021. Nessana Necropoleis: An Aerial and Ground Survey of Byzantine Era Cemeteries in the Israeli Negev. Antigua Oriente 19: 277-300. Tchekhanovets Y., Rasiuk A., Levy A., Peretz A. and Pogorelsky O. 2023. The Renewed Excavations at Nessana. In: A. Golani, D. Varga, S. Rosen and Y. Tchekhanovets (eds.), Archaeological Excavations and Research Studies in Southern Israel. 19th Annual Southern Conference. Beer-Sheva (Hebrew). (forthcoming). (1990-1991), 103-104.

- links to online versions of some of these are at the Nessana Expedition Website

Peretz A. and Betzer P. 2022. Hospital, Tents and Graves: Auja el-Hafir in World War I. In: A. Golani, D. Varga, Y. Tchekhanovets and M. Birkenfeld (eds.), Archaeological Excavations and Research Studies in Southern Israel. 18 th Annual Southern Conference. Beer-Sheva. Pp. 111–128 (Hebrew).

MaH. D. Colt et al., Excavations at Nessana 1, London 1962

L. Casson and E. L. Hettich,

Excavations at Nessana 2: Literary Papyri, Princeton 1950

C. J. Kraemer, Excavations at Nessana 3: NonLiterary Papyri, Princeton 1958.

Musil, Arabia Petraea 1: Edam, 88-109

Woolley-Lawrence PEFA 3, 115-121

P. H.

Haensler, Das Heilige Land 60 (1916), 155ff.

61 (1916), 198ff.

62 (1917), 12ff.

K. Wultzinger and

T. Wiegand, Sinai, Berlin 1921, 99-109

A. A1t, Die griechischen Inschriften der Palaestina Tertia, Berlin

1921, 37-43

B.S. J. lsserlin, Annual, Leeds University 7 (1969-1973), 17-31

A. Negev, RB 81 (1974),

400-422

id., MdB 19 (1981), 16, 32

id., Antike Welt 13 (1982), 2-33

id., Tempel, Kirchen und Cisternen,

Stuttgart 1983, 193-296, 215-223

id., BAR 14/6 (1988), 36-37

D. Chen, LA 35 (1985), 291-296;

R. Wenning, Die Nabatadr: Denkmdler undGeschichte, Gottingen 1987, 156-158

D. Urman, BAlAS 10

(1990-1991), 103-104.

D. Urman et al., Nessana Excavations 1987–1995 (Nessana Excavations and Studies 1; Beer Sheva 17), Beer-Sheva 2004 (Heb.)

A. Negev, ABD, 4, New York 1992, 1082–1084

id., Eretz Magazine 8/30 (1993), 35–52

id., Studies

in the Archaeology and History of Ancient Israel, Haifa 1993, 25*

id., Petra Rediscovered: Lost City of the

Nabataeans (ed. G. Markoe), London 2003, 101–105

P. Figueras, Aram 6 (1994), 279–293

id., Atti del Congresso Internationale di Archeologia Cristiana 12, Roma 1995, 756–762

id., LA 45 (1995), 401–450 (pp.

425–430)

P. Mayerson, Monks, Martyrs, Soldiers and Saracens: Papers on the Near East and Late Antiquity

(1962–1993), Jerusalem 1994, 21–39

J. Zias et al., International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 5 (1995),

157–163

R. Rubin, ZDPV 112 (1996), 49–60

id., Journal of Historical Geography 23 (1997), 267–283

id.,

Mediterranean Historical Review 1998, 56–74

L. Di Segni, Dated Greek Inscriptions from Palestine from

the Roman and Byzantine Periods (Ph.D. diss.), 1–2, Jerusalem 1997

A. Lynd-Porter, OEANE, 4, New York

1997, 129–130

S. R. Wolff, IEJ 47 (1997), 93–96

H. Goldfus, Tombs and Burials in Churches and Monasteries of Byzantine Palestine (324–628 A.D.), 1–2 (Ph.D. diss.), Ann Arbor, MI 1998, 80–89

J. Magness,

The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine, Winona Lake, IN 2003, 90–91, 176–185

D. J.

Wasserstein, SCI 22 (2003), 257–272

T. Goodwin, PEQ 137 (2005), 65–76.