Mizpe Shivta

Mizpe Shivta and environs on govmap.gov.il

Mizpe Shivta and environs on govmap.gov.ilclick on image to explore this site on a new tab in govmap.gov.il

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Mizpe Shivta | Hebrew | |

| Khirbet el-Misrafa | Arabic | |

| Khirbat al-Mushrayfa | Arabic | |

| el-Meshrifeh | Arabic | |

| Mesrafeh | Arabic | |

| Mishrafa | Arabic |

The ruins of Mizpe Shivta (in Arabic, Khirbet el-Misrafa) are in the central Negev, at the eastern edge of a large spur and on the low horseshoe-shaped terrace surrounding it (map reference 1126.0364). The site consists of a complex of buildings comprising a single unit, whose area is 160 by 180m. E. H. Palmer (see below) suggested identifying the site with biblical Zephath (Jg. I: 17), but no finds predating the Byzantine period have been uncovered. According to its excavator, it should be identified with the "fortress and inn of Saint George," where the traveler known as Antoninus of Placentia stayed on his way from Elusa to Sinai in about 570 CE (Itinerarium 35; CCSC 175, 146-147). Saint George is mentioned in one of the inscriptions found at the site.

Following Palmer's discovery of the site in 1871 and publication of its plan, it was visited by A. Musil, in 1901, who also drew a plan of it; by C. L. Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, in 1914, who surveyed it and gave a detailed account of their findings, and measured the church; and by T. Wiegand, in 1916, who did a survey and took aerial photographs. In 1979, the site was surveyed again as part of the Emergency Survey of the Negev by Y. Baumgarten, who excavated the site on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums.

As Woolley and Lawrence had correctly discerned, Mizpe Shivta was the site of a monastery, perhaps a laura. The cellars may initially have served as a place of seclusion for a single monk (Saint George?), around which the monastery developed. The walls and towers have created the impression that this was a fortress; however, it should be noted that the monasteries established in Palestine in the Byzantine period were surrounded by defensive walls. This apparently is the reason why at the end of the sixth century the traveler from Placentia described the site as the "fortress and inn of Saint George."

Two building phases can be distinguished: the first is characterized by fine construction, whereas in the second several changes occurred. The western gate was blocked by masonry; additions (of inferior quality) were made to the northern structures on the summit; and a set of crude steps was built, leading from the summit to the lower terrace in the eastern part of the site. Judging from the extent of the destruction and debris, the site may have been struck by an earthquake. Only Byzantine pottery was found on the floors of the rooms, particularly in the church. The site showed no signs of violent destruction and was apparently abandoned after the rooms' contents had been removed

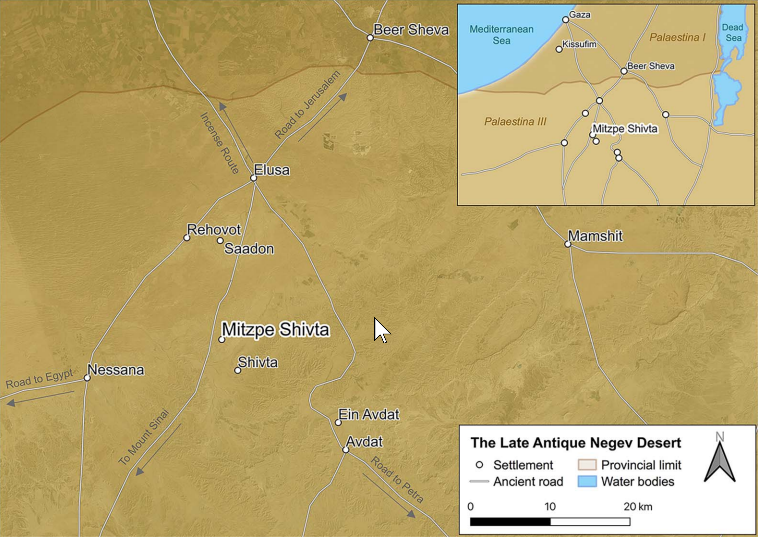

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Lehnig et al. (2023)

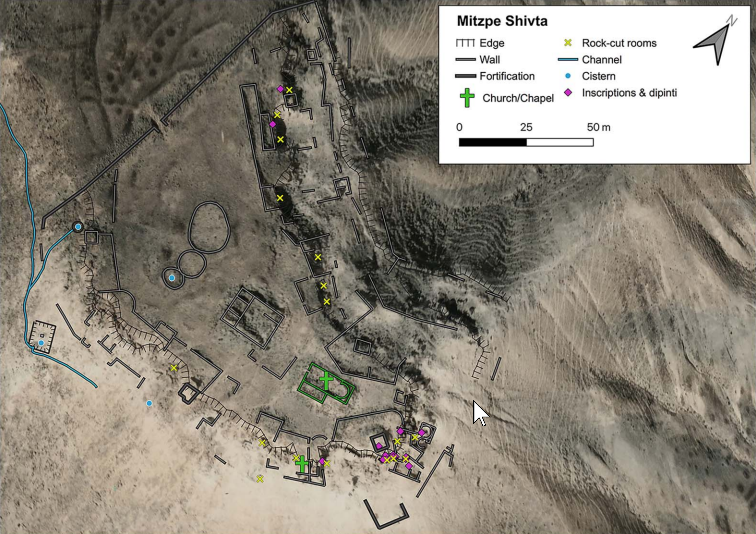

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of the

site from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 historic aerial photograph

of the site with plans superimposed from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Mizpe Shivta and environs in Google Earth

- Mizpe Shivta and environs on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of the

site from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 historic aerial photograph

of the site with plans superimposed from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Mizpe Shivta and environs in Google Earth

- Mizpe Shivta and environs on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of the

site from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 historic aerial photograph

of the site with plans superimposed from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Site plan from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Mizpe Shivta: general plan of the site.

Mizpe Shivta: general plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of the

site from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 historic aerial photograph

of the site with plans superimposed from Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Site plan from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Mizpe Shivta: general plan of the site.

Mizpe Shivta: general plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

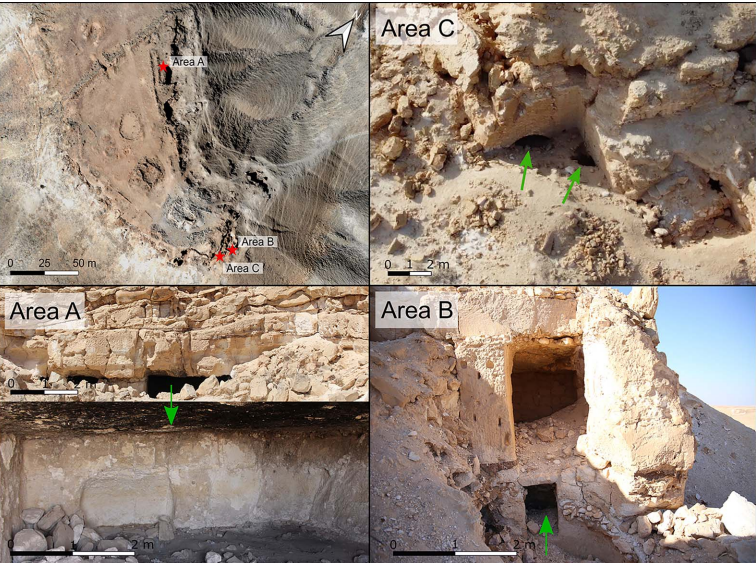

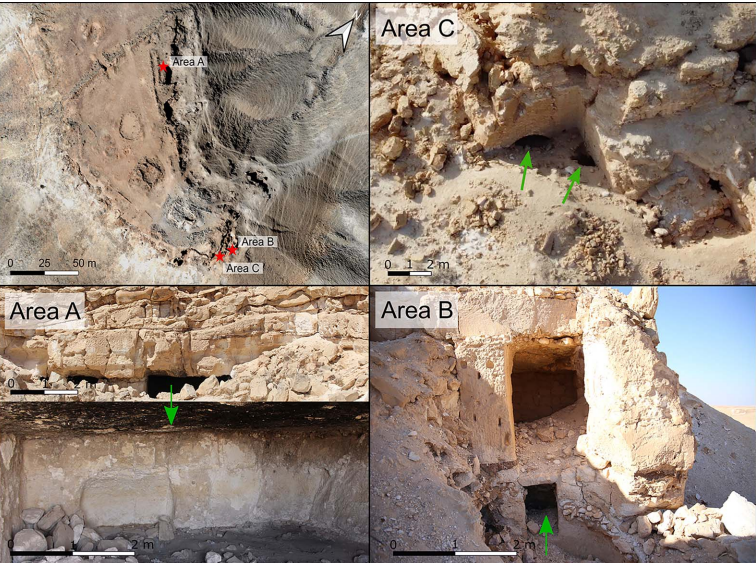

- Fig. 4 Master Aerial Shot of

Areas A, B, and C from Lehnig et al. (2023)

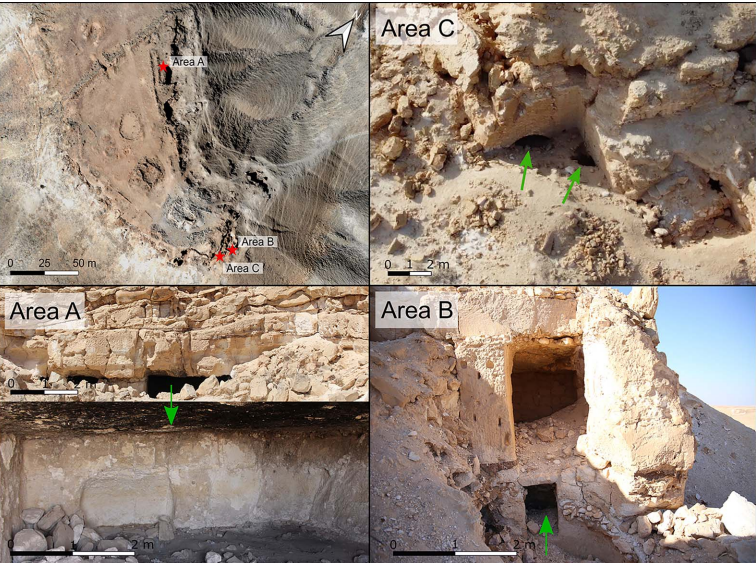

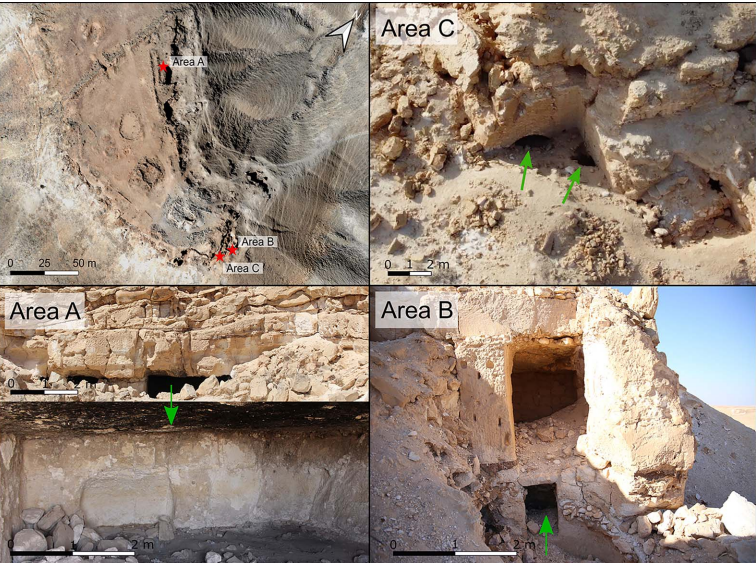

Figure 4

Figure 4

Locations of the three selected study areas:

- Area A: three continuous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace

- Area B: a small rock-cut niche that connects a mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building

- Area C: a rock-cut complex with two entrance arches

(figure by the authors).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Areas A, B, and C

from Lehnig et al. (2023)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Locations of the three selected study areas:

- Area A: three continuous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace

- Area B: a small rock-cut niche that connects a mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building

- Area C: a rock-cut complex with two entrance arches

(figure by the authors).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2023)

- Fig. 4 Master Aerial Shot of

Areas A, B, and C from Lehnig et al. (2023)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Locations of the three selected study areas:

- Area A: three continuous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace

- Area B: a small rock-cut niche that connects a mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building

- Area C: a rock-cut complex with two entrance arches

(figure by the authors).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Areas A, B, and C

from Lehnig et al. (2023)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Locations of the three selected study areas:

- Area A: three continuous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace

- Area B: a small rock-cut niche that connects a mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building

- Area C: a rock-cut complex with two entrance arches

(figure by the authors).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2023)

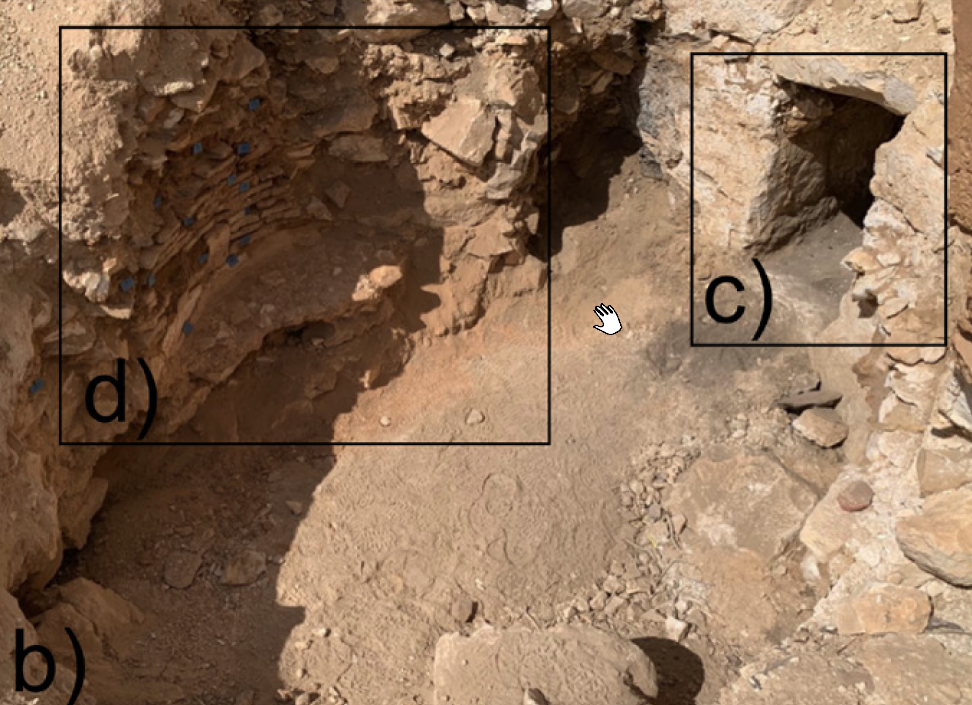

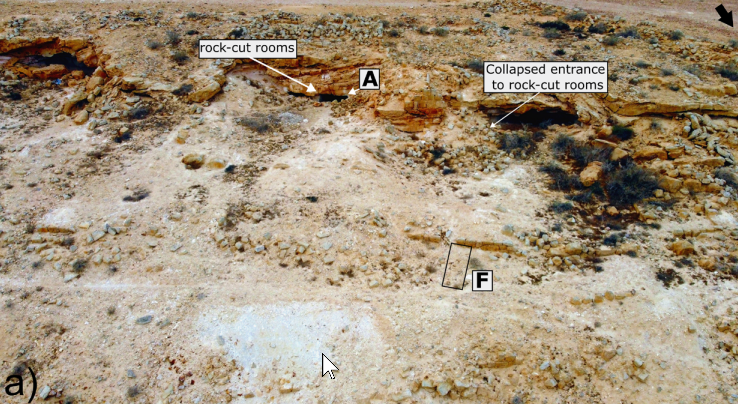

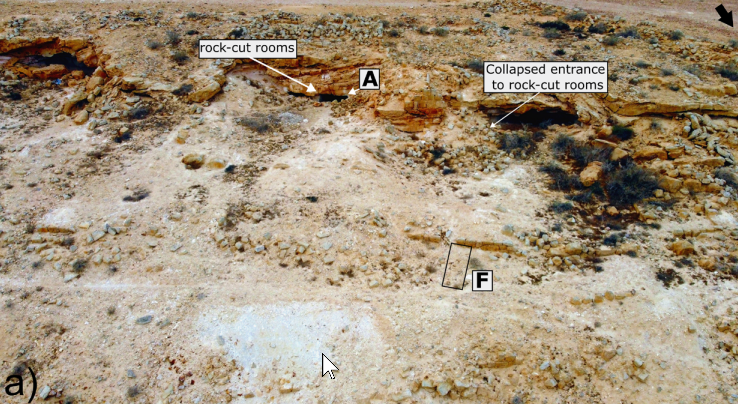

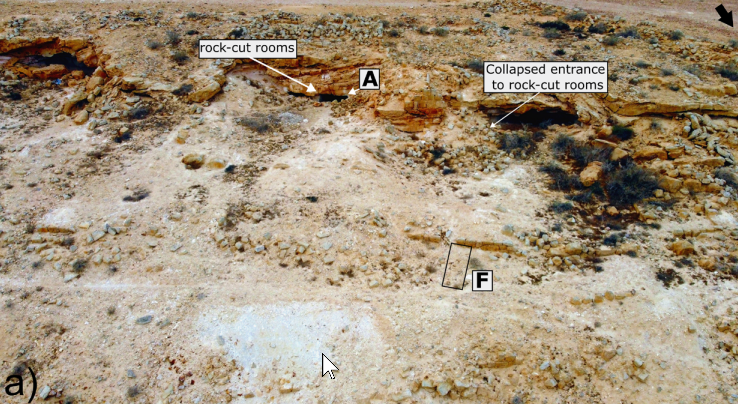

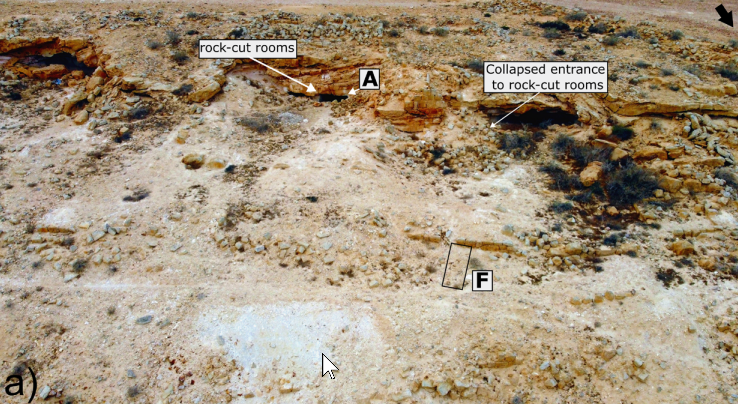

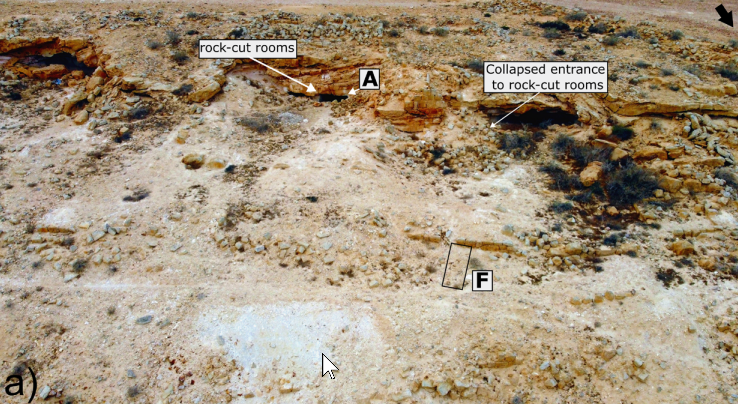

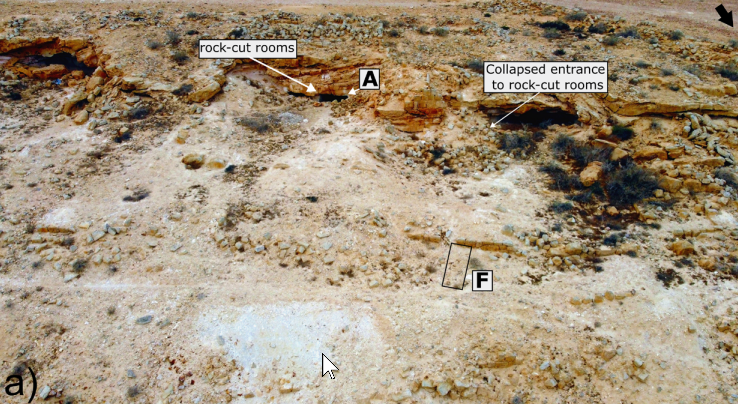

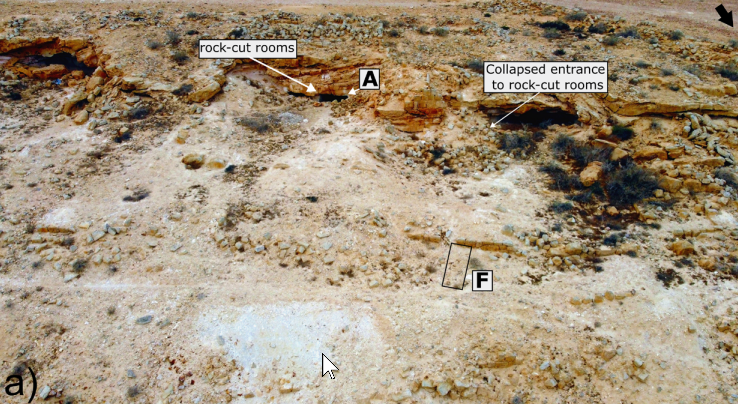

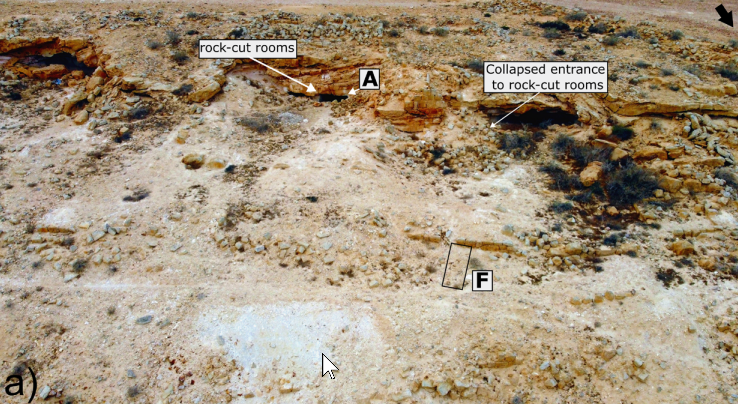

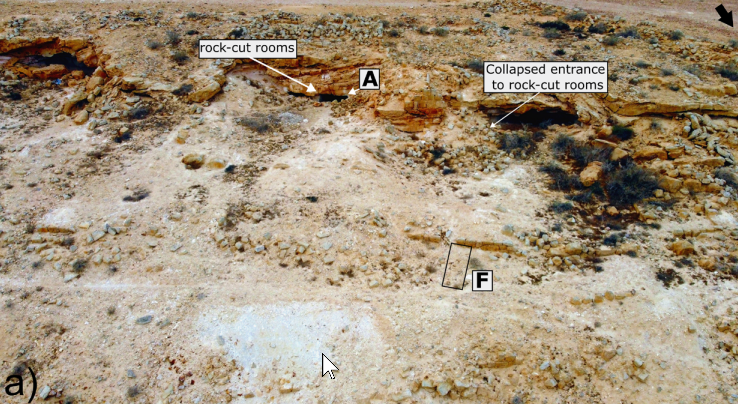

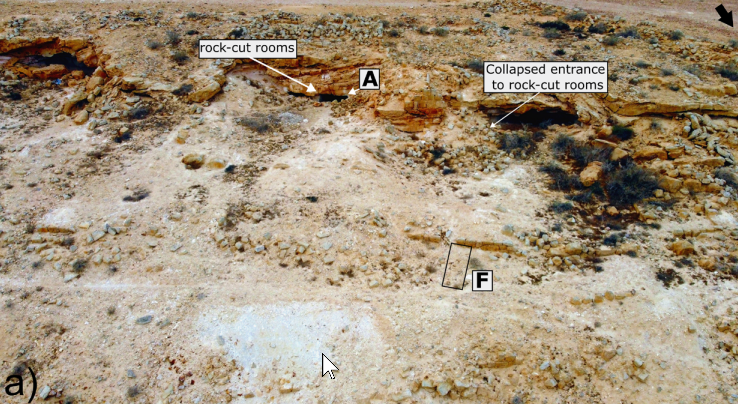

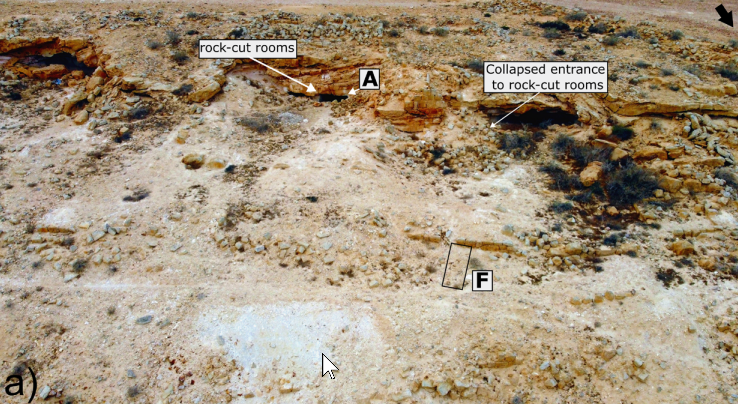

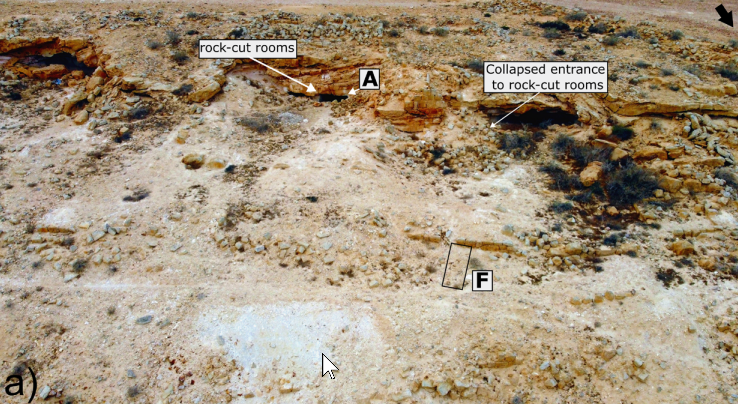

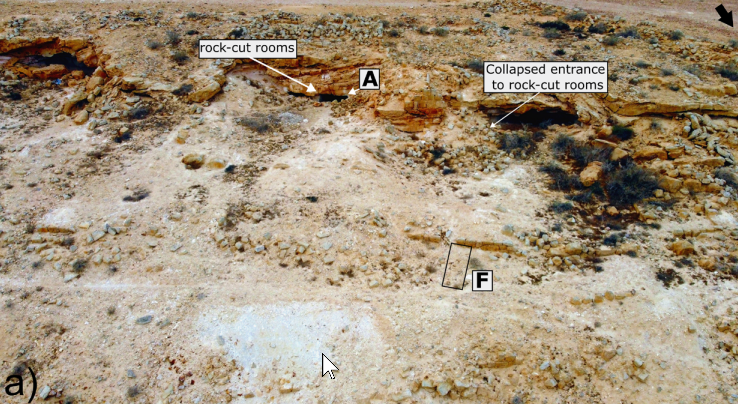

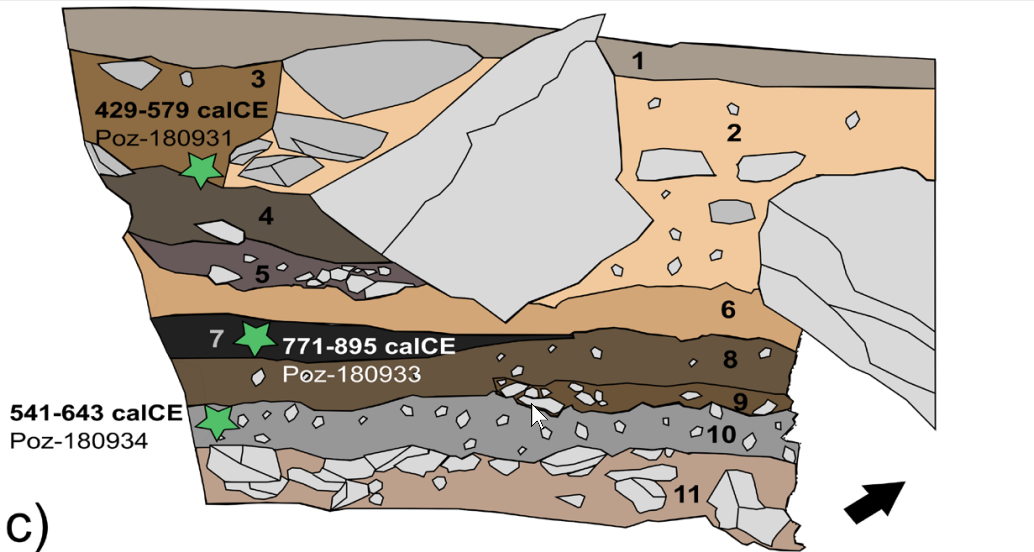

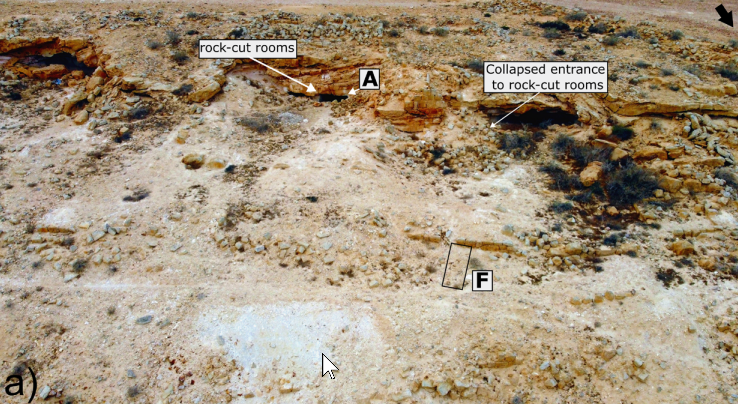

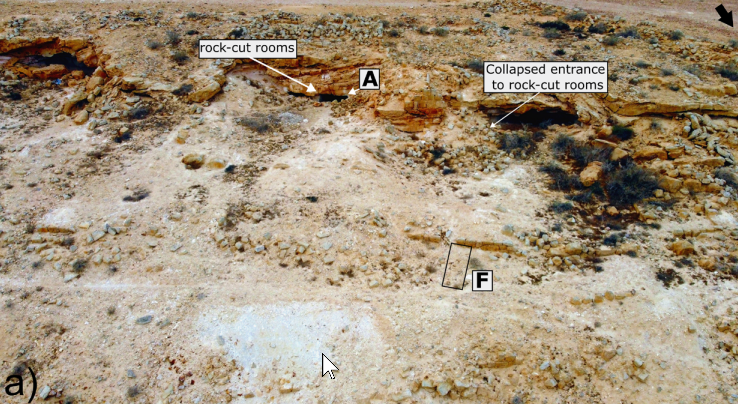

- Fig. 8a Location of

Areas A and F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8a

Figure 8a

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 8a Location of

Areas A and F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8a

Figure 8a

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6a Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6b Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6c Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6d Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 7a Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7a

Figure 7a

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7b Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7b

Figure 7b

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7c Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7c

Figure 7c

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7d and 7e Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7d and 7e

Figure 7d and 7e

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7e Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7e

Figure 7e

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7f Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7f

Figure 7f

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8a Location of Areas A and F

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8a

Figure 8a

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

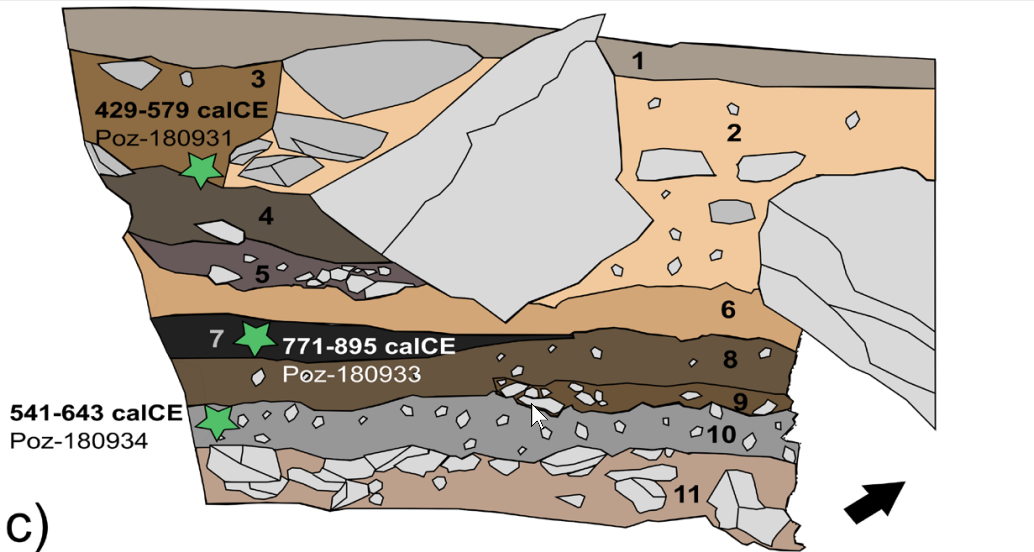

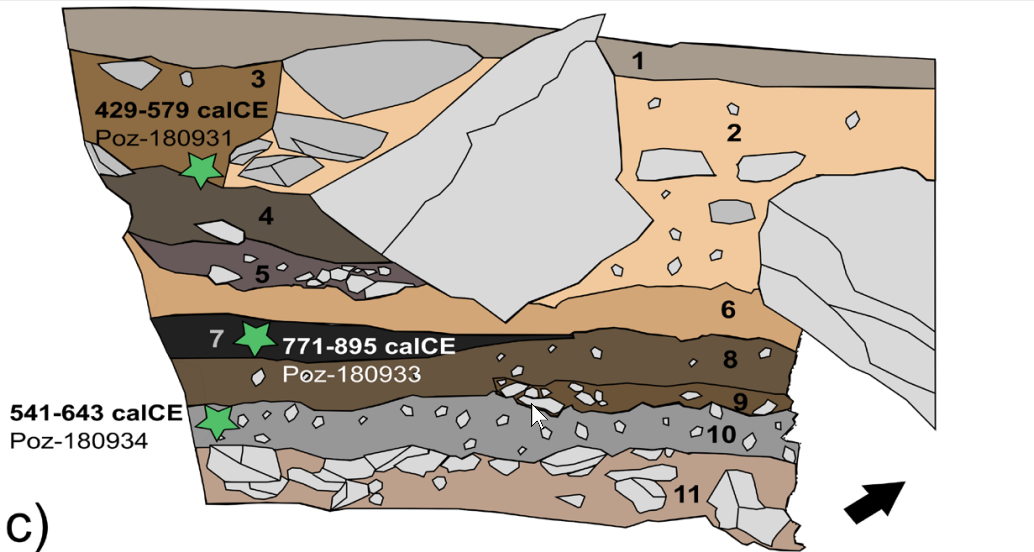

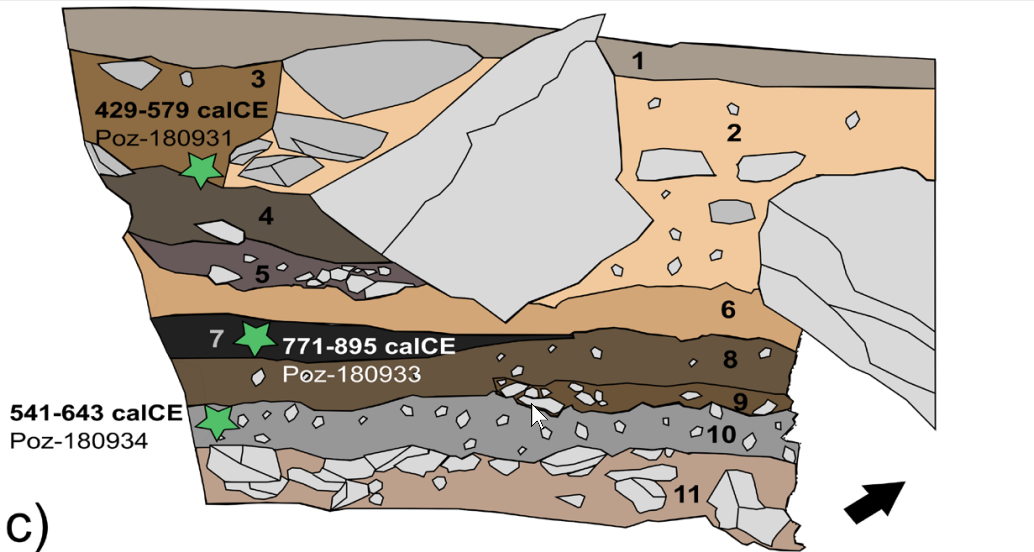

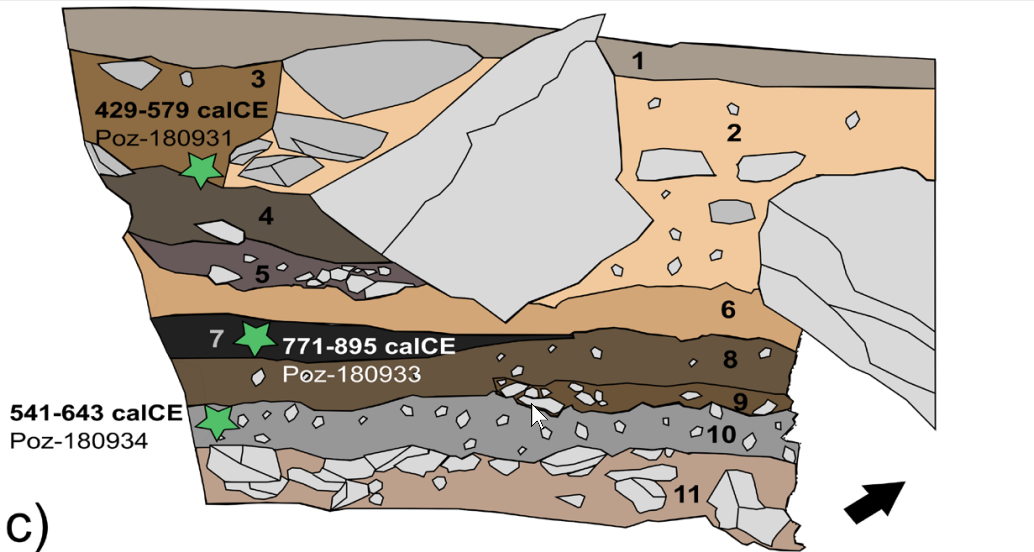

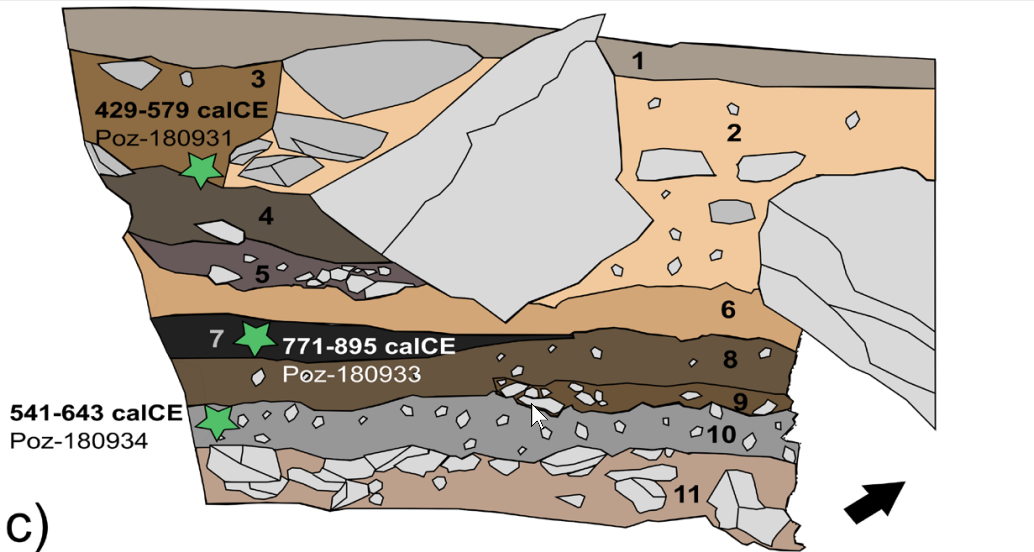

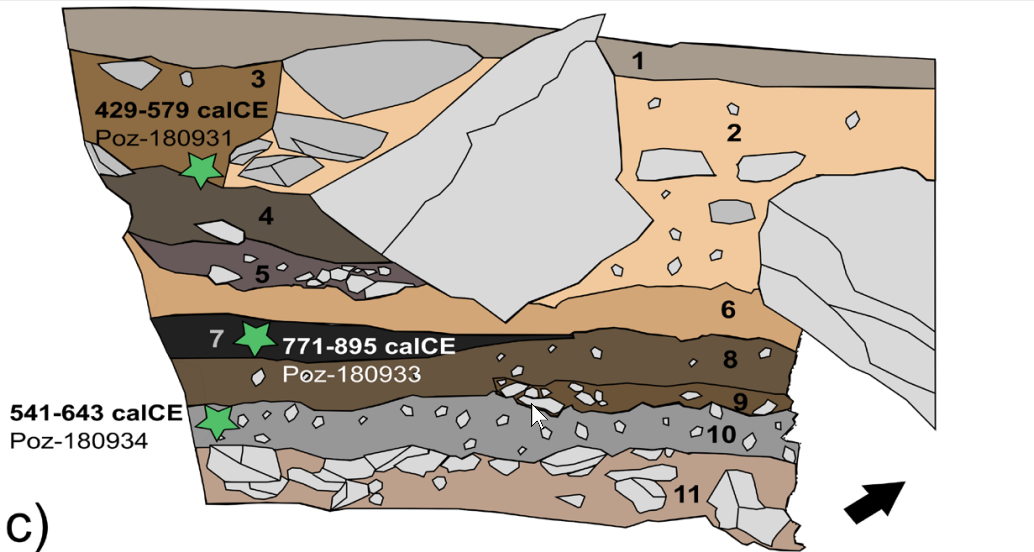

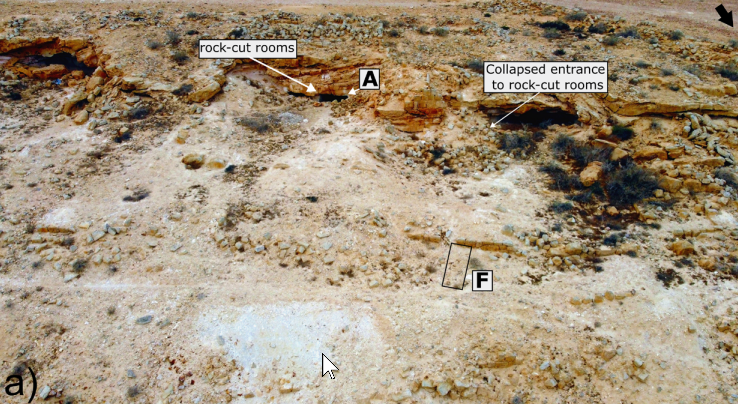

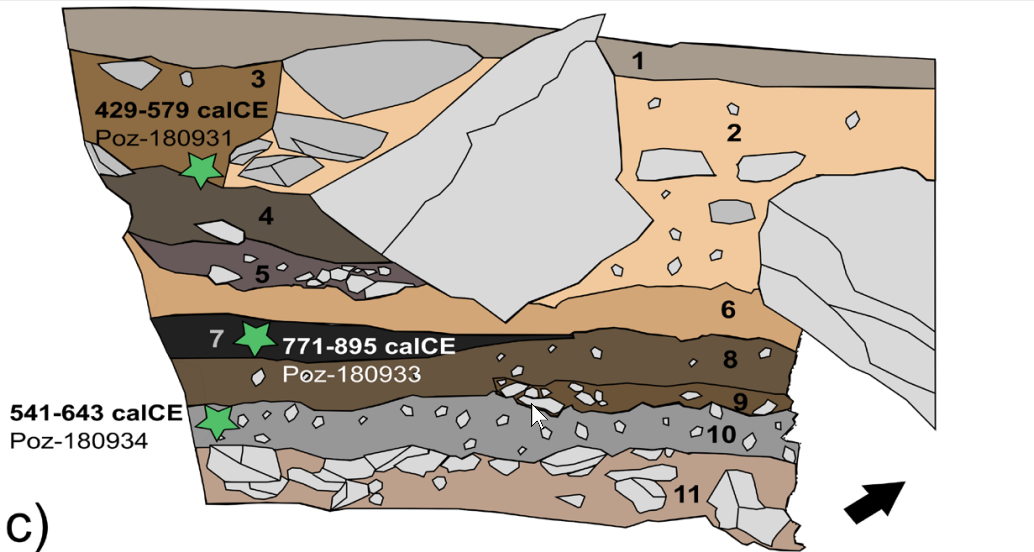

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8b Area F balk

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8b

Figure 8b

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8c Area F balk

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8c

Figure 8c

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8d Area F pottery

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8d

Figure 8d

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

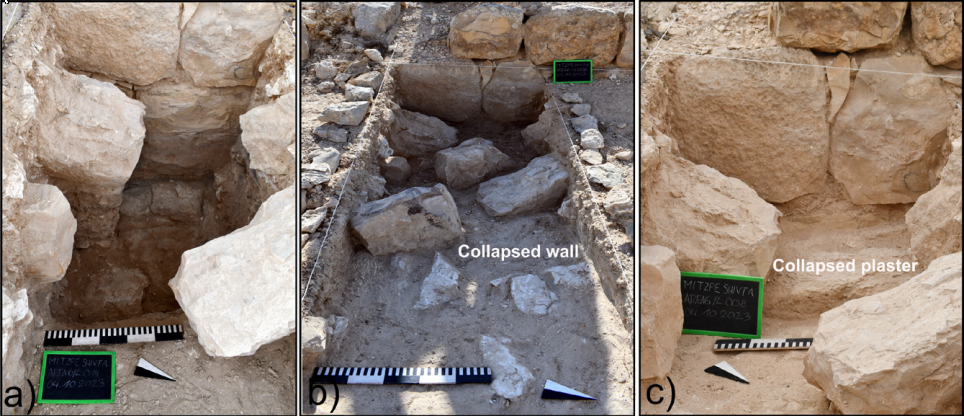

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 9 Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9a Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9b Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9c Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10a Revetement Arch

at the entrance to one of the rock-hewn rooms from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10b Displaced Voissoirs

and spalled corners of an arch in the SW tower from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10c Aerial photo

of southwest tower from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6a Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6b Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6c Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 6d Area B photos

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 7a Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7a

Figure 7a

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7b Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7b

Figure 7b

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7c Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7c

Figure 7c

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7d and 7e Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7d and 7e

Figure 7d and 7e

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7e Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7e

Figure 7e

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 7f Sampling locations in Area C

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 7f

Figure 7f

Sampling locations in Area C

- (a) and in two entrance arches

- (c, d) leading into several adjoining rock-hewn rooms; wall plaster surrounding arch of eastern room sampled for radiocarbon dating

- (c); inscriptions and dipinti featured on both arches and in room interior

- (b, e, f). One of the inscriptions

- (f) is dated to 577/8 CE (Figueras, 2007)

(photographs by S. Lehnig).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8a Location of Areas A and F

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8a

Figure 8a

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8b Area F balk

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8b

Figure 8b

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8c Area F balk

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8c

Figure 8c

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 8d Area F pottery

from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Figure 8d

Figure 8d

Location of Areas A and F

- (a); stratigraphy of Area F

- (b); balk section in Area F with location of radiocarbon samples

- (c); pottery from Layer 11 (juglet base and bag-shaped jars from the Late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods), wall plaster samples from Layer 6 debris, parrotfish jaw from Layer 11

- (d)

(photographs by S. Lehnig, J. Linstädter).

click on image to open in a new tab

Lehnig et al. (2025a) - Fig. 9 Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9a Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9b Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 9c Collapsed wall

and wall plaster in Area F from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10a Revetement Arch

at the entrance to one of the rock-hewn rooms from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10b Displaced Voissoirs

and spalled corners of an arch in the SW tower from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

- Fig. 10c Aerial photo

of southwest tower from Lehnig et al. (2025a)

Yaacov Baumgarten in Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) noted that two building phases were distinguished.

New excavations and radiocarbon data from Mitzpe Shivta—a site closely linked to monasticism and pilgrimage—enable to locate, for the first time, the previously overlooked site within the broader chronology and cultural-historical narrative of the Negev Desert (Israel). While early explorers emphasized a Late Byzantine-period (550–638 CE) settlement of the site, our investigations provide evidence of continued habitation from the Middle Byzantine period (450–550 CE), extending into Abbasid times. Radiocarbon data demonstrate that the site’s occupation may have begun as early as the mid-5th– mid-6th century CE, paralleling it with established models concerning the development of monasteries and pilgrimage networks in Palestine and Egypt.

By this time, Negev settlements such as the neighboring Shivta and Nessana had reached their zenith of agricultural and economic development, providing infrastructure for travelers to Mount Sinai. Inscriptions discovered in Mitzpe Shivta’s rock-hewn rooms, dedicated to Saint George, align with pilgrim accounts, such as the one supplied by the Piacenza Pilgrim, which reveal that the veneration of saints played a crucial role in shaping the religious landscape of the region. Thus, Mitzpe Shivta may have attracted devotees seeking the intercession of Saint George and other similar martyrs.

Our study reveals that Mitzpe Shivta remained inhabited following the local agricultural decline in the late 6th century CE and into the Islamic period. The discovery of grape seeds dating to the Abbasid period may indicate continued use of the site by Christians. These findings align with evidence of other monastic and Christian communities’ resilience in the Negev during the Islamic period. It is possible that Mitzpe Shivta was abandoned in the 8th/9th century CE following a local earthquake and decreased pilgrimage tourism under the Abbasid dynasty.

Mitzpe Shivta (Arab.: el-Meshrifeh, Khirbet el-Misrafa, Khirbat al-Mushrayfa, Mesrafeh, Mishrafa) is located in the central Negev Desert, along one of the main Holy Land pilgrimage routes that connected Jerusalem and Gaza on the Mediterranean shore, Mount Sinai and Egypt (Fig. 1; 162556-839/536385-606). It is 5 km from the Byzantine settlement of Shivta and on the main route to Elusa (22 km to the north). Its location on a hilltop (460 m a.s.l.) allows observation of the entire periphery, toward areas that were intensively used for agriculture in Byzantine times. The site's main features (Fig. 2) include a perimeter wall encircling upper and lower fortresses, towers with arrow-slits, a church, a small chapel, domestic units, a courtyard house, a large cistern, a channel and numerous rock-hewn rooms with built and natural facades (Lehnig et al., 2023). The interiors of the rooms are decorated with well-preserved wall plaster, inscriptions and paintings of crosses (Gambash et al. 2023). The buildings' exteriors were covered with white plaster (Lehnig et al., 2025).

Before this research, Mitzpe Shivta had been studied only superficially and thus could not contribute to a better understanding of the role of monasteries and pilgrimage during the rise and fall of the Negev agricultural society by the end of the Byzantine period and their afterlife following the Islamic conquest. The complex was first described by Palmer (1871: 371–374), who referred to it as a fort. Later, Lawrence and Woolley (1914: 108 ff.) labeled it a Byzantine monastery with elements of a "laura". During World War I, the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand considered Mitzpe Shivta to be a Byzantine "Mistenburg" (engl. desert castle) and "Bollwerk" (engl. stronghold) built to protect the road between Elusa and Aila (Wiegand, 1920: 118). Baumgarten (1986) conducted a small-scale excavation in 1979, which concentrated on the church. The results were only partially published, and a detailed analysis of archaeological material and a sound dating of the site were not produced. Baumgarten interpreted the site as a Late Byzantine (550–638 CE) monastic settlement with hermit caves, based on the pottery finds. He observed damage caused by an earthquake but did not suggest a precise date for the event. Figueras (2007) discovered and published three inscriptions out of a significantly larger number covering the entrances and interiors of the rock-hewn rooms. One of the published inscriptions was suggested by Figueras to include the date 577/8 CE. He employed another inscription in order to identify Mitzpe Shivta as a castrum and xenodochium for pilgrims, perhaps matching the one mentioned in the Itinerarium of the Piacenza Pilgrim (PP /Itin. 35). The same inscription mentions Saint George and points to the veneration of soldier saints, typical of Negev monasteries. A training camp for infantry soldiers established in the 1960s just below the archaeological site eventually became a training base for artillery in the 1990s. While other Negev settlements had undergone a period of extensive research during these decades, Mitzpe Shivta has been overlooked by Negev explorers.

Our previous investigations, including the discovery of 17 new inscriptions, support the view that Mitzpe Shivta held importance for pilgrimage and monasticism. The names in the inscriptions suggest that the site was frequented by locals and passersby, some of who possessed decent literacy abilities and knowledge of the Scriptures. Previous 14C data from our initial probe excavations (Lehnig et al., 2023) showed that occupation extended beyond the 6th century CE— an era marked by the decline of a short-lived late antique agricultural florescence of the Negev Desert and the gradual abandonment of villages (Avni et al., 2023). Likewise, recent archaeological discoveries at the settlements of Avdat (Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020; Bucking et al., 2022) and Nessana (Tchekhanovets, 2024) revealed ongoing habitation, possibly connected to monastic communities and their involvement in viticulture and pilgrimage tourism (Kraemer, 1958; Pogorelsky et al., 2019). These findings suggest that Byzantine culture continued within monastic enclaves during the Early Islamic period, while in contemporary settlements there may have been prohibitions against wine production and its consumption (Fuks et al., 2020). The same was true for the consumption of pork, which is absent in archaeozoological records of most Early Islamic-period Negev sites (Marom et al., 2019).

Mitzpe Shivta represents a largely unstudied archaeological archive, offering valuable insights into the agricultural, economic and social roles of monasteries during the Byzantine– Early Islamic transition and beyond. As a rural monastery it can provide new perspectives on this unexplored type of settlement, and due to its proximity to Shivta, it may be linked to chronological developments in larger agricultural villages in the Negev. In our project we employed a multidisciplinary research protocol to conduct excavations and sampling in different areas of the site, focusing on rock-cut rooms and connected stone-built compounds. Our goals were to reconstruct the cultural history of the site by clarifying its stratigraphy and dating its various archaeological contexts. In this article we outline the current knowledge of the site's chronology by presenting the new radiocarbon data from our excavations. Since pottery finds are not particularly frequent at Mitzpe Shivta, the establishment of an initial 14C chronology is of great importance for understanding the site's history.

Excavations and sampling at Mitzpe Shivta took place during two campaigns in the autumns of 2022 and 2023, with the aim of characterizing for the first time the settlement’s history, chronology and function in terms of monasticism, pilgrimage and local economy. Two investigations targeted the rock-cut spaces typical of the site (Areas A and B), while two others focused on buildings made of local marl limestone and flintstone that are situated in front of these spaces (Areas C and F; Fig. 3). These dual architectural compounds, featuring rock-cut spaces and standing masonry, bear typological similarities to those discovered at the Byzantine–Early Islamic settlement of Avdat. Previous studies at Avdat have associated these structures with monastic establishments and their activities, including animal husbandry, wine production and pilgrimage economy (Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020; Bucking et al., 2022). Stone-built rooms in Areas D and E, adjacent to Area F, are connected to the rock-cut rooms in Area A. So far, these have been documented only by surface surveying. Their layout and the visible masonry and plaster cladding suggest an economic/industrial function, possibly a wine press.

We divided the excavation areas into 1 sq m units, which were explored in 10 cm deep spits, measured using an RTK GNSS receiver with LT 1 cm precision for mapping. All excavated sediments were dry sieved through a 5 mm mesh to retrieve small artifacts and biological remains. Sediment samples were collected for flotation of botanical remains, as additional samples, for chronometric determinations (14C) and geoarchaeological analysis. In addition, we took wall plaster samples to date charcoal inclusions and analyze mineralogically the plaster's composition.

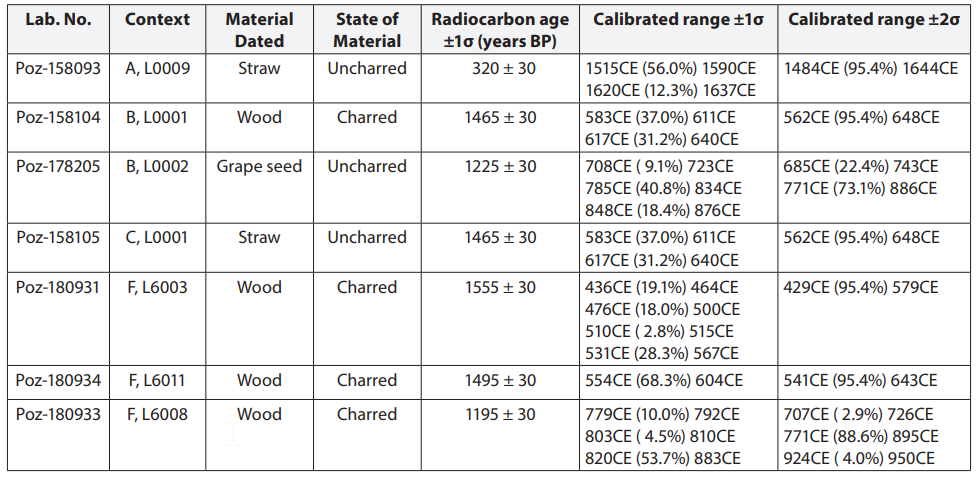

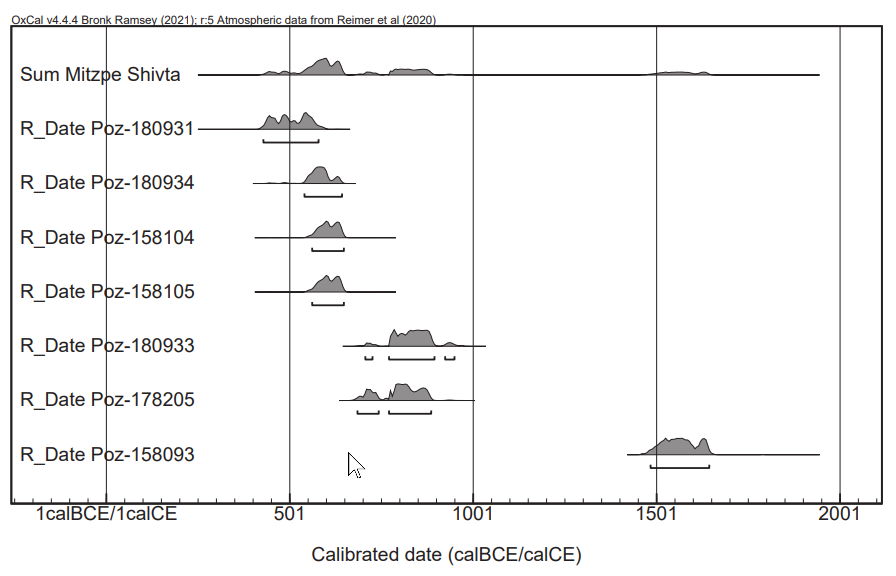

Table 1 presents the samples collected for radiocarbon dating, including their material, condition and archaeological context. These comprise an uncharred straw fragment from Area A, an uncharred grape seed and a charcoal fragment from Area B, an uncharred straw fragment from the plaster of the outer wall of the rock-cut room in Area C and selected charcoal samples from various stratigraphic layers in Area F. The samples were sent to the Poznan Radiocarbon Laboratory. The complete analytical procedure for organic samples such as charcoal and other plant remains, including chemical pre-treatment using the three-step AAA method (acid-alkali-acid), combustion of the sample and AMS measurement, is described on the laboratory's website (https://radiocarbon.pl/en/sample-preparation/). The 14C age was calibrated using the OxCal program, version 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009) with the newest version of 14C calibration curve IntCal20 (Reimer et al., 2020).

Area A (Fig. 4) comprises a unit of three contiguous rock-cut rooms on the lower, northern terrace of the site. The rooms are hewn out of the soft local marl limestone of a plateau, on top of which are the church and other buildings. Intensive quarrying traces that cover the walls of the rooms illustrate this process (Fig. 4d). In front of them and on the same level, remains of a stone building are partly preserved. Immediately above the rock-cut rooms is a building made of massive ashlars that corresponds to the layout of the lower stone building (Fig. 3b, c).

Our main point of interest was the first of the three rooms, which is presently accessible from the north through a rock-cut entrance 0.6 m high and 2.5 m wide (Fig. 3b). The room's plan (Fig. 3c) is a perfect square (5.8 x 5.8 m). A small niche was carved out into the rock in the southern wall of the room (Fig. 4b), and in the northwestern corner there is a low, roughly worked passage to the second room of the complex. A cross was carved on the eastern wall (Fig. 4d); its arms narrow toward the center, classifying it as a Christian cross /Jaffee. The Greek letter P (Rho) on the cross's right side may indicate that this is a variant of a Christogram. The only other decorated walls are in one of the rooms adjacent to the first room, where the wall plaster bears remnants of red ink (Fig. 4e).

During our survey of the room, we found a 1.0 x 1.3 m looting trench adjacent to the rock facade, immediately below the cross (Fig. 4c). Such forms of looting near inscriptions, crosses or petroglyphs—commonly associated with markers for buried treasures—are known also at other sites in the Negev region (Lior Schwimer, pers. comm.). We found the trench with collapsed sections, filled with sediment and remains of animal dung, plants and modern garbage, including the scraps of a newspaper from 1973, when the site was already within the boundaries of the training ground of the neighboring Shivta Base.

An initial cleanup of the trench indicated a good preservation of organic material with charcoal suitable for radiocarbon dating and micro- geoarchaeology. We consequently cleaned the entire trench out, from the surface down to bedrock, to a depth of 0.9 m. Following this, we extended the area of the trench by 0.5 m to the south and conducted an excavation in 10 cm spits. The excavation of the upper three layers (L.1001–1003) revealed an accumulation of light to dark ashy soil with inclusions of limestone, twigs, fresh livestock dung pellets and modern remains. In addition, in all three layers we found few pottery fragments dating to the Byzantine period (bag-shaped jars), as well as animal bones and remains of textiles. In the following layer (L.1004) we perceived a significant change in the nature of the sediment, with straw and animal dung compacted to about 5 cm thick of very solid matrix. This horizon was again followed by a layer (L.1005) of loose gray-brown ash with inclusions of dung pellets and animal bones, with pottery dated to the British Mandate period. We found a particularly fine brown sediment in the lower three layers (L.1007–1009), above the bedrock, interspersed with animal bones and Early Islamic cooking ware. We also found a large worked wooden fragment in L.1008—probably part of a piece of furniture or a peg. The rock-cut floor at the bottom of the trench was mostly even and had probably been hewn similarly as the walls of the room to create a level living floor (Fig. 4c). A straw fragment from just above the bedrock was sent for radiocarbon dating. The calibrated date falls between 1484 calCE and 1644 calCE, within the Ottoman period (Tab. 1, Fig. 5).

Area A yielded several identified animal bones that were distributed evenly in the section. These include long bones and teeth of both adult and juvenile sheep or goats, a burnt pelvis and a molar tooth of an adult camel. Some of the bones bear evidence of carnivore gnawing.

Area B (Fig. 6a), on the eastern slope of the site, presents a roughly oval structure partly carved into the local rock and partly built of thin bricks (Fig. 6b). The structure's western side had been somewhat deformed by the pressure of natural rocks that had collapsed, sediment and architectural fragments—possibly the result of seismic activity. Some of the debris filled the structure's interior. We uncovered the remains of a floor made of compacted clay and lime at the elevation of the base of the brick structure. It was only partially preserved, near the walls of the oval structure, and its center had collapsed (Fig. 6d).

A small niche (Fig. 6c), which is part of a larger rock-cut building, adjoins the oval structure in the north and opens into it. Its upper part was filled with debris, and the lower part, with light to dark grayish ash. To clarify the function and date of the oval structure and niche, we initially focused on cleaning the debris in the structure, sampling the ashy niche fills for micro-geoarchaeological investigations and collecting two samples for 14C dating. The results indicated usage between late antiquity and the Early Islamic period, extending into the Abbasid era (562 calCE–648 calCE). The dating of an uncharred grape seed (771 calCE–886 calCE) further reinforces Abbasid-period occupation (Tab. 1; Figs 5, 6e).

Ceramic material retrieved during the cleaning of the oval structure dates to the Byzantine period. Several roof tiles (e.g., Fig. 6f) were recovered inside it and in its immediate vicinity. These finds, usually associated with church buildings in the Negev, may have originated in the basilica located directly above the excavation site, in the upper fortress, and tumbled down during an earthquake. Other finds include a fish vertebra, most probably of a Gilt-head bream (Sparus aurata).

Located in the southeastern part of the site (Fig. 7a), Area C consists of an arch made of ashlars, likely forming a window or entrance to a unit of several rock-cut rooms (Fig. 7c). The investigated arch and the neighboring ones (Fig. 7d) are inscribed with pilgrim graffiti. One inscription mentions Saint George, while another includes the year 577/8 CE, precisely dating the pilgrim's visit to the site (Figueras, 2007; Fig. 7b, e, f). Additional inscriptions of pilgrim names and invocations have been analyzed recently by the authors (Gambash et al., 2023). The archway was likely buried by architectural debris that had fallen over it during an earthquake and later partially exposed by looters. The exterior facade was covered with white plaster, some of which is still preserved. We sampled straw fragments embedded in the mixture for radiocarbon analysis, to determine when the wall had been plastered. While the results point to a date between the late 6th and mid-7th centuries CE (562 calCE–648 calCE; Tab. 1 and Fig. 5), we cannot determine with certainty whether this is also the date of the initial construction of the building. Nevertheless, this result conforms with the date of the pilgrim inscription published by Figueras, which was likely added on the plaster slightly later, in 577/8 CE.

Area F (Fig. 8a) was opened on the northern part of the lower fortress of Mitzpe Shivta to investigate and date the building complex in front of the rock-cut space in Area A. For our investigation we selected a section of the northern closing wall (W.6001) of the building complex. One stone row of this wall was visible and preserved to a height of 40 cm above the surface prior to its excavation, indicating that it was constructed as double-shell ashlar masonry with a rubble fill. The stones of the wall were hewn from locally quarried chalkstone of the Nizzana Formation and contain flint inclusions. We excavated a 1 x 2 m trench along the wall in 10 cm spits, reaching its foundation and the bedrock at a depth of 1.6 m below surface. The total preserved height of the examined wall is 2 m.

In contrast to the rock-cut space in Area A, which was reused during the Ottoman and British Mandate periods, the stratigraphy in Area F was undisturbed. After the excavation, we identified distinct stratigraphic layers in the remaining section (Fig. 8b, c). Immediately below the topsoil (1), which contained a mix of Byzantine and Early Islamic pottery, were layers that can be associated with the collapse of Wall 6001 (Fig. 9). All along the trench we discovered the collapsed upper ashlar sections of the wall (2). The ashlars showed signs of heat exposure, evidenced by flintstone fragments that had flaked off the chalkstone. The gaps between the ashlars were filled with small limestone fragments. Signs of intense heat exposure are visible also in the layer closest to the wall (3), in the form of a concentration of charcoal. Below the layers of collapsed ashlars was a layer (6) of well-preserved wall plaster with an orange-white color (Figs 8d, 9). On the segments of the wall that had not collapsed we found remnants of this wall plaster still attached to the ashlar stones. The layers (7, 8) underneath the wall plaster showed a concentration of ash and burnt plant material, along with numerous sherds of Early Islamic fine ware and many bone fragments, all of which also exhibited signs of heat exposure. Beneath these burnt layers were layers (9, 10) exhibiting a higher concentration of artifacts, including pottery dating from the 6th–8th centuries CE, glass and parrotfish teeth (Fig. 8d). The final stratum (11) above the bedrock consisted of a compacted layer of larger and smaller limestone fragments, likely laid intentionally to level the surface.

We collected charcoal samples from three contexts for radiocarbon dating (Fig. 8c). The sample from the lowest layer (10) dates to the mid-6th–mid- 7th centuries CE (541 calCE–643 calCE; Tab. 1, Fig. 5). The sample from the burnt layer (7) was dated to the Abbasid period and may indicate the abandonment of the settlement, or the building, following an earthquake or fire between the late 8th and late 9th centuries CE (771 calCE–895 calCE). Remarkably, it was the layer immediately beneath the topsoil (3) that yielded the sample with the earliest 14C date obtained for Mitzpe Shivta so far, in the early 5th–late 6th centuries CE (429 calCE–579 calCE).

Inscriptions left by pilgrim tourists and paintings of crosses on the entrance ways of rock-cut rooms, as well as the presence of a church, suggest that Mitzpe Shivta was closely linked to both pilgrimage tourism and monastic life. Additionally, a possible identification of the site as the hostel for pilgrims and hermits described by the Piacenza Pilgrim in the mid-6th century CE further reinforces the archaeological and epigraphic evidence. Inscriptions dedicated to Saint George may indicate that the site itself served as a place of worship specifically for the veneration of soldier saints (Figueras, 2007; Gambash et al., 2023). This suggests that Mitzpe Shivta may have attracted devotees seeking the inter-cession of Saint George and other similar martyrs, pos-sibly positioning the settlement as a local center for the cult of soldier saints in the region.

The earliest radiocarbon date from Area F so far may be interpreted as evidence that Mitzpe Shivta was already inhabited in the 5th century CE, during the Middle Byzantine period. This date may be supported also by the epigraphy of recently discovered inscrip-tions at the site, which conforms with that of other local 5th–6th centuries CE texts (Gambash et al., 2023: 216). With this preliminary chronological framework, Mitzpe Shivta would integrate smoothly into established models of monastery development and pilgrimage networks in the southern Levant (Hamarneh, 2012). However, the charcoal sample that provided this date requires critical evaluation, having been recovered in the latest archaeological layer, above the 8th/9th-cen-tury CE layer. It may be that the sample originated in an older wooden structure—possibly a roof—that was attached to the building in Area F, which had collapsed during an earthquake and burned. We cannot deter-mine, however, whether the 5th-century CE date of the wood corresponds with the roof's construction date. It is possible that the wood originally served a different function and was only repurposed at a later point to build the roof. Therefore, the idea of a 5th-century CE settlement needs further scrutiny. Solid radiocarbon data and ceramic and epigraphic finds from the 6th century CE, however, clearly indicate that the site was settled by then at the latest.

Christian pilgrimage in the Holy Land and Sinai was already well established by the 6th century CE, with key sites such as Mount Sinai, associated with the eponymous biblical site and having long attracted the faithful (Caner 2010). Early pilgrimage routes, as docu-mented by travelers like Egeria in the 4th century CE, largely bypassed the Negev. Pilgrims preferred the well-trodden Via Maris, running along the coast between Gaza and Pelusium in Egypt, which provided safer pas-sage. However, by the mid-6th century CE, there was a significant shift in pilgrimage patterns. The account of the Piacenza Pilgrim, written some 200 years after Egeria, reveals a new route through the Negev Desert. Unlike his predecessors, the Piacenza Pilgrim did not merely seek out biblical sites; instead, he was also drawn to the relics of saints and martyrs, which had become central to the pilgrimage experience by this time. The Byzantine Negev settlements, including Mitzpe Shivta, gained prominence as locations offering access to the veneration of local saints and possibly relics, marking a new phase in the development of pilgrimage. It was primarily the settlements located in the northern and central Negev Desert that economically benefited from pilgrimage tourism. In the settlements of Elusa and Rehovot in the northern Negev, as well as in Nessana and Shivta farther south, numerous church buildings testify to the wealth that this economic sector brought to the settlements (Tsafrir, 1988; Heinzelmann et al., 2022; Tchekhanovets, 2024).

Available evidence suggests that the rise of Mitzpe Shivta was closely linked to the broader shift in pilgrimage in the mid-6th century CE. By this time, the settlements of the Negev had reached their zenith in terms of economic and agricultural development (Avni et al., 2023), providing infrastructure that could be utilized by travelers. The demographic expansion and agricultural intensification of the desert region made travel less hostile and its destinations more hospitable than they had been in earlier centuries. At the same time, Justinian's further development of monasticism around Mount Sinai intensified the incoming pilgrimage (Seveenko, 1966; Frazee, 1982: 263–279). Artwork at Shivta depicts the transfiguration of Christ and shares stylistic aspects with paintings found in the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Mount Sinai (Linn et al., 2017), emphasizing Shivta's historical and religious significance in the pilgrimage movement and, more broadly, for Christianity (see also Maayan-Fanar and Tepper, 2023, 2024). Mitzpe Shivta, located in the agricultural hinterland of Shivta, was likely part of this pilgrimage network, though its precise relationship to Shivta remains a subject of ongoing investigation.

In the Negev and elsewhere the intensification of pilgrimage likely increased the logistical challenges of providing for the travelers' needs, including security, food and accommodation, during their journey (Jensen, 2020). The Piacenza Pilgrim's report reveals that the inn at Mitzpe Shivta catered to both pilgrims and hermits. However, the specifics of this provisioning—such as the arrangements for lodging and food—remain invisible in the archaeological record so far. The presence of a moderate-sized fortification at Mitzpe Shivta suggests that concerns for safety were paramount, possibly in response to the threat of attacks on travelers and monks, often reported in travelogues (Caner, 2010: 48–51). In this respect, Mitzpe Shivta is similar to other contemporary monasteries that were enclosed by walls, and some furnished with towers (see Hamarneh, 2012: 282).

Accounts suggest that food and accommodation were frequently offered to pilgrims at no cost, and Mitzpe Shivta may have supplied this vital service in the Negev (Jensen, 2020: 148). To date, our investigations have yielded only preliminary insights into the subsistence strategies employed at the site. The discovery of fish bones dating to the Byzantine period indicates the import of marine resources from the Mediterranean and Red Seas, reflecting the characteristic Byzantine foodways of the Negev (Gambash et al., 2019; Blevis et al., 2021; Ktalav et al., 2021). The large, unbuilt area with traces of agricultural structures on the plateau of Mitzpe Shivta, still visible in early 20th-century aerial photographs (Wiegand, 1920; Lehnig et al., 2025), may indicate plant cultivation within the settlement's walls. Future architectural investigations and botanical analyses of plant-rich material that has been excavated may illuminate the diet of the site's occupants and consequently help to reconstruct monastic nutrition in the Negev and to understand how pilgrims were provided for.

Research at Mitzpe Shivta further emphasizes that the local veneration of saints played a crucial role in shaping the religious landscape of the Negev region during the 6th century CE. Pilgrims left inscriptions and graffiti at new centers of devotion, creating clusters of commemorations at sites such as Mitzpe Shivta, in the Saints' Cave and the dipinti-intensive cave at Avdat (Bucking, 2017) and in the churches of Shivta (Maayan-Fanar and Tepper, 2023, 2024). This phenomenon suggests that these settlements had developed their own religious significance, distinct from the pilgrimage sites that are more traditionally associated with the Holy Land. The inscriptions often request assistance from God or from saints, such as Saint George at Mitzpe Shivta, Saint Theodore at Avdat and Sergius and Bacchus at Nessana (Negev 1981: 43; Bucking, 2017: 28–43; P. Colt 45; 46; 51). This indicates that the veneration of soldier saints may have been a central attraction for pilgrims in the Negev and the expression of the religious self-conception of the churches and monasteries in the desert settlements. Rock-cut rooms and caves, which are abundant at Mitzpe Shivta and Avdat, appear to have been a particular point of attraction as indicated by the various crosses and inscriptions we discovered in them. Rock-cut rooms in the Negev served multifaceted functions, as livestock stables, storage spaces and tombs (Erickson-Gini, 2022), hindering a secure identification of their uses at Mitzpe Shivta. In many well-known monasteries in the Judean Desert and Egypt, rock-hewn rooms or natural caves were inhabited by hermits and monks (Hedstrom and Dey, 2020). Often, such solitary dwellings (laurae) marked the first stage of settlement, where an individual hermit would establish a base; over time, a larger monastic community with the necessary economic and religious infrastructure (coenobium) would grow around him (Hirschfeld, 1990). A similar developmental trajectory may be proposed for Mitzpe Shivta with its central church building, rock-hewn rooms, enclosure wall and possibly a hostel for pilgrims. However, it is difficult to determine the function of the rock-hewn rooms at the site during the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods, as they were reused in the Ottoman and British Mandate periods, as evidenced by radiocarbon dating and ceramic analysis. The dung-rich layers in Area A demonstrate that the Byzantine settlement layers were cleared possibly during the Ottoman period, and the rock-cut spaces were subsequently used by shepherds as animal shelters. Thus, evidence of their religious significance, possibly as monk cells and pilgrim attractions, are limited to inscriptions and cross paintings and to their decor, with plaster-covered niches.

According to radiocarbon data, Mitzpe Shivta remained settled well beyond the Byzantine period, though it is uncertain whether the site continued to serve as a pilgrimage destination and monastery or underwent functional changes during the Early Islamic period. While no inscriptions definitively postdate the 6th century CE, evidence of grape seeds from the 8th/9th century CE may indicate wine consumption or the cultivation of grapes, closely tied to the production of wine, both suggesting the possibility of ongoing Christian presence, as the consumption of alcohol was often prohibited in Early Islamic settlements (Fuks et al., 2020).

Elsewhere in the Negev, there is tangible evidence of Christian and monastic resilience into the Early Islamic period. Pilgrimage continued between the 7th and 9th centuries CE, as documented by inscriptions in neighboring Shivta (Tchekhanovets et al., 2017) and papyrological evidence of travelers and their guides (P. Colt 72; 73) who navigated the desert routes to reach key Christian sites, including Mount Sinai and Jerusalem.

By the Abbasid period, the scale of monasticism and pilgrimage in Palestine had diminished significantly (Patrich, 2011; Killzer, 2020: 14). The comprehensive routes of earlier centuries, which had spanned the Negev and linked holy sites, were largely abandoned, as the new dynasty showed no interest in sustaining infrastructure in peripheral regions and shifted priorities to Iran and Iraq (Haiman, 1995: 46, 48). Textile finds at Nahal Omer indicate that trade routes connected the Arava with Arabia and Central Asia (Bar-Oz et al., 2024). It is therefore possible that routes shifted from the Mediterranean region and central Negev to the Arava in the east, establishing economic links with the northern regions of the Abbasid Empire. Christian pilgrims, however, increasingly favored the sacred sites in Jerusalem and its surrounding areas as journey destinations, leading to the weakening of the pilgrimage infrastructure that had once sustained settlements such as Mitzpe Shivta.

Radiocarbon data of charcoal fragments sealed within the destruction layers of Area F suggest that the site was abandoned by the 8th/9th century CE following an earthquake and subsequent conflagration and was never rebuilt. Collapsed arches, twisted roof slabs and fallen sections of the upper fortress are also ubiquitous above ground in other areas of Mitzpe Shivta (Fig. 10c). Retaining walls (Fig. 10a) and double arches (Fig. 10b) at the site and the use of double-shell masonry indicate that buildings in the settlement were designed to withstand earthquakes, and efforts were made to stabilize individual structures, possibly following an earlier seismic event. Nevertheless, it appears that an earthquake eventually managed to devastate the site, bringing an end to its occupation. Radiocarbon data indicate that the rock-hewn rooms of Mitzpe Shivta were reused only from the 15th/17th century CE onward, when they served shepherds as livestock shelters.

Several seismic events have been identified as having impacted settlements in the Negev over time (Korjenkov et al., 1996; Korjenkov and Mazor, 1999; Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini, 2003). Damage from an 8th- or 9th-century CE earthquake has been documented in buildings of the neighboring Negev sites of Shivta, Avdat and Rehovot (Erickson-Gini, 2013; Korjenkov and Mazor, 2014; Tepper et al., 2018: 149; Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020: 51). This suggests that the seismic event that led to the destruction documented at Mitzpe Shivta affected the broader Negev region. Between 746 and 757 CE, ancient authors such as Theophanes described at least three sizeable earthquakes in the region of Palestine, Jordan and Syria (Amiran et al., 1994; Ambraseys, 2009: 230–238; Avni, 2014: 300–343). Although they are depicted as universally catastrophic, it is doubtful that these historically recorded earthquakes were responsible for the seismic destructions in the Negev settlements. Studies point rather to a regional diversity in the effects of earthquake damage, with sites in the north being more affected than those in the south of Palestine (Marco et al., 2003). It is therefore likely that the chronicled earthquakes impacted the Negev settlements at most peripherally, and that it was a separate, local earthquake that brought about the destruction at Mitzpe Shivta and other nearby Negev settlements like Shivta (Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020: 51). One may assume that the site was not rebuilt due to overall economic instability in the Negev, exacerbated by the region's peripheral political position during the Abbasid period. Thus, the fate of Mitzpe Shivta reflects broader shifts in the religious, political and economic dynamics of the region, tied closely to the rise and fall of pilgrimage and agriculture as a defining feature of the landscape.

Having been largely overlooked by generations of Negev explorers, our recent excavations and radiocarbon dating position Mitzpe Shivta within the broader chronology and cultural-historical narrative of the Negev. While previous scholars were led to classify Mitzpe Shivta as a Late Byzantine- era site and monastery, based primarily on the abundance of pilgrim inscriptions and presence of rock-hewn rooms, radiocarbon data demonstrate that occupation may have begun as early as the 5th century CE and extended far beyond the late 6th-century CE decline of agriculture in the Negev and the subsequent Islamic conquest. With this preliminary chronological framework, Mitzpe Shivta integrates smoothly into established models of the development of monasteries and pilgrimage networks in Palestine and Egypt. Archaeological evidence suggesting that most monastic structures in the region began to emerge from the mid-5th century CE is often corroborated by earlier textual references. These settlements likely evolved in tandem with the rise of Christian pilgrimage routes and the expansion of rural settlements, as monasteries often served as important spiritual and logistical hubs for pilgrims and were involved in the administration of agricultural activities. By the 6th century CE, many of these monastic communities had reached their zenith, both in terms of size and religious significance. Radiocarbon dates and inscriptions closely tie Mitzpe Shivta to the 6th-century CE intensification of pilgrimage directed toward the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Mount Sinai. This appears to have paralleled the development of local saint cults that arose at key sites like Mitzpe Shivta, Avdat, Nessana and potentially other locations across the Negev, transforming these sites into important nodes for pilgrimage and local veneration alike. This marks a significant evolution from earlier pilgrimage patterns, in which travelers primarily sought out locations of direct biblical significance. The veneration of soldier saints, such as Saint George at Mitzpe Shivta, was a prominent feature of this new devotional landscape.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, Mitzpe Shivta was inhabited until its destruction— likely by a local earthquake and subsequent conflagration in the 8th/9th century CE. Whether it continued to serve as a monastery and pilgrimage destination during the Islamic period or if its functional role changed remains undetermined and awaits further research. Should it emerge that Mitzpe Shivta retained its Christian identity and continued to receive pilgrims after the Islamic conquest, it would align with broader regional trends. Across the southern Levant and the Negev several Christian settlements and monasteries not only remained active during the Early Islamic period but also flourished, maintaining religious practices, constructing churches and continuing to serve as important pilgrimage destinations. It was only under the Abbasid dynasty that the pilgrimage routes in the Negev gradually saw a significant decline in activity. The once bustling paths frequented by religious travelers began to fall out of use, as the course of major travel routes shifted eastward toward the Arava Valley. This strategic shift connected Arabia with the broader commercial networks of Central Asia. Rather than facilitating religious pilgrimage, these routes increasingly served the needs of merchants, becoming critical arteries for trade and the movement of goods across vast distances. The extent to which the abandonment of Mitzpe Shivta was connected to these broader shifts in trade routes and the region's reorientation remains a subject for further research. Equally, the role of the earthquake and fire we documented, which likely contributed to the site's eventual desertion, requires additional investigation to understand fully its impact in conjunction with these changes.

- Clarify the causes underlying the exploitation of ancient building material during the Late Ottoman Period; including the general attitude towards cultural heritage within the empire.

- Reconstruct which structures in Mitzpe Shivta were affected by destruction and how this altered the site’s appearance.

- Establish whether the bridges and channels adjacent to Mitzpe Shivta were indeed the final destinations for the archaeological material mined at the site, exploring how it was treated and recycled.

- Evaluate Wiegand’s legacy as an archaeologist in the Negev and his lasting impact on the understanding of Mitzpe Shivta’s history and the protection of the site, particularly in light of his appointment as the head of the »German Turkish Commando for Monument Protection«.

- The topography of the Negev with its numerous wadis made it necessary to build bridges and channels[33], which required materials, time and manpower.

- A shortage of materials had already become apparent during construction in the north, which is why old railroad lines were dismantled and recycled.

- The large-scale resettlement of Armenians diverted significant resources, and the subsequent genocide resulted in a loss of know-how and labor.[36]

- Concurrent British efforts on a Sinai railway and water pipeline intensified time pressure on the Ottoman-German railway construction.

- Workers unfamiliar with the arid climate suffered from heat and supply shortages, resulting in casualties.[37]

- Wiegand links Mitzpe Shivta seamlessly with other Byzantine settlements such as Oboda (Hebr.: Avdat, Arab.: Abde), Sobata (Hebr.; Shivta, Arab.: Subeita), Nessana (Hebr.: Nizzana, Arab.: Auja al Hafir), and Rehovot (Arab.: Khirbet Ruheibeh), perceiving them to share a common tradition.

- He particularly emphasizes the fortification aspect of the settlement, giving significant importance to the stone-built architectural elements.

- Ottoman-employed railroad contractors exploited archaeological sites for construction purposes.

- Towers on the southern side of Mitzpe Shivta, closest to the railway, were consequently destroyed.

- The primary focus was on extracting well-dressed cornerstones and lintels, leading to destabilization of the remaining structure.

- This exploitation aimed to avoid the necessity of hiring and paying stonemasons.

- While Armenian and other Christian minorities were being persecuted in other parts of the Ottoman Empire in 1916, they contributed to the construction of the railway in the Negev.

- Wiegand’s observations prompted measures by the Ottoman military to be taken against the destruction of archaeology.

- Topography played a crucial role in determining the placement of passages within the embankment.

- The size of the wadis influenced the choice between small channels and larger, sometimes multi-arched bridges.

- Despite the time constraints evident in the railway’s construction, aesthetic considerations were not disregarded (Fig. 20). Architectural elements, such as the Bossage technique[88] on the arches (OB 007), were employed for their visual impact. This Rustication style, commonly found in military structures like forts and castles, conveys a sense of power and strength. Despite its seemingly simplistic appearance, the method demands skilled stonemasons to achieve a coarse finish.

- Additional aesthetic features include the meticulously smoothed keystones of the bridges and side wings, showcasing traces of various stonemason tools. Notably, a block from OB 005 reveals intricate craftsmanship, merging distinct styles of the vault and side wings within a single stone.

- Contrary to Wiegand’s claim that the quarrying of ancient stones by railway contractors aimed to save on personnel and salaries, the bridges provide evidence of the work of highly skilled stonemasons.

New excavations and radiocarbon data from Mitzpe Shivta—a site closely linked to monasticism and pilgrimage—enable to locate, for the first time, the previously overlooked site within the broader chronology and cultural-historical narrative of the Negev Desert (Israel). While early explorers emphasized a Late Byzantine-period (550–638 CE) settlement of the site, our investigations provide evidence of continued habitation from the Middle Byzantine period (450–550 CE), extending into Abbasid times. Radiocarbon data demonstrate that the site’s occupation may have begun as early as the mid-5th– mid-6th century CE, paralleling it with established models concerning the development of monasteries and pilgrimage networks in Palestine and Egypt.

By this time, Negev settlements such as the neighboring Shivta and Nessana had reached their zenith of agricultural and economic development, providing infrastructure for travelers to Mount Sinai. Inscriptions discovered in Mitzpe Shivta’s rock-hewn rooms, dedicated to Saint George, align with pilgrim accounts, such as the one supplied by the Piacenza Pilgrim, which reveal that the veneration of saints played a crucial role in shaping the religious landscape of the region. Thus, Mitzpe Shivta may have attracted devotees seeking the intercession of Saint George and other similar martyrs.

Our study reveals that Mitzpe Shivta remained inhabited following the local agricultural decline in the late 6th century CE and into the Islamic period. The discovery of grape seeds dating to the Abbasid period may indicate continued use of the site by Christians. These findings align with evidence of other monastic and Christian communities’ resilience in the Negev during the Islamic period. It is possible that Mitzpe Shivta was abandoned in the 8th/9th century CE following a local earthquake and decreased pilgrimage tourism under the Abbasid dynasty.

Mitzpe Shivta (Arab.: el-Meshrifeh, Khirbet el-Misrafa, Khirbat al-Mushrayfa, Mesrafeh, Mishrafa) is located in the central Negev Desert, along one of the main Holy Land pilgrimage routes that connected Jerusalem and Gaza on the Mediterranean shore, Mount Sinai and Egypt (Fig. 1; 162556-839/536385-606). It is 5 km from the Byzantine settlement of Shivta and on the main route to Elusa (22 km to the north). Its location on a hilltop (460 m a.s.l.) allows observation of the entire periphery, toward areas that were intensively used for agriculture in Byzantine times. The site's main features (Fig. 2) include a perimeter wall encircling upper and lower fortresses, towers with arrow-slits, a church, a small chapel, domestic units, a courtyard house, a large cistern, a channel and numerous rock-hewn rooms with built and natural facades (Lehnig et al., 2023). The interiors of the rooms are decorated with well-preserved wall plaster, inscriptions and paintings of crosses (Gambash et al. 2023). The buildings' exteriors were covered with white plaster (Lehnig et al., 2025).

Before this research, Mitzpe Shivta had been studied only superficially and thus could not contribute to a better understanding of the role of monasteries and pilgrimage during the rise and fall of the Negev agricultural society by the end of the Byzantine period and their afterlife following the Islamic conquest. The complex was first described by Palmer (1871: 371–374), who referred to it as a fort. Later, Lawrence and Woolley (1914: 108 ff.) labeled it a Byzantine monastery with elements of a "laura". During World War I, the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand considered Mitzpe Shivta to be a Byzantine "Mistenburg" (engl. desert castle) and "Bollwerk" (engl. stronghold) built to protect the road between Elusa and Aila (Wiegand, 1920: 118). Baumgarten (1986) conducted a small-scale excavation in 1979, which concentrated on the church. The results were only partially published, and a detailed analysis of archaeological material and a sound dating of the site were not produced. Baumgarten interpreted the site as a Late Byzantine (550–638 CE) monastic settlement with hermit caves, based on the pottery finds. He observed damage caused by an earthquake but did not suggest a precise date for the event. Figueras (2007) discovered and published three inscriptions out of a significantly larger number covering the entrances and interiors of the rock-hewn rooms. One of the published inscriptions was suggested by Figueras to include the date 577/8 CE. He employed another inscription in order to identify Mitzpe Shivta as a castrum and xenodochium for pilgrims, perhaps matching the one mentioned in the Itinerarium of the Piacenza Pilgrim (PP /Itin. 35). The same inscription mentions Saint George and points to the veneration of soldier saints, typical of Negev monasteries. A training camp for infantry soldiers established in the 1960s just below the archaeological site eventually became a training base for artillery in the 1990s. While other Negev settlements had undergone a period of extensive research during these decades, Mitzpe Shivta has been overlooked by Negev explorers.

Our previous investigations, including the discovery of 17 new inscriptions, support the view that Mitzpe Shivta held importance for pilgrimage and monasticism. The names in the inscriptions suggest that the site was frequented by locals and passersby, some of who possessed decent literacy abilities and knowledge of the Scriptures. Previous 14C data from our initial probe excavations (Lehnig et al., 2023) showed that occupation extended beyond the 6th century CE— an era marked by the decline of a short-lived late antique agricultural florescence of the Negev Desert and the gradual abandonment of villages (Avni et al., 2023). Likewise, recent archaeological discoveries at the settlements of Avdat (Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020; Bucking et al., 2022) and Nessana (Tchekhanovets, 2024) revealed ongoing habitation, possibly connected to monastic communities and their involvement in viticulture and pilgrimage tourism (Kraemer, 1958; Pogorelsky et al., 2019). These findings suggest that Byzantine culture continued within monastic enclaves during the Early Islamic period, while in contemporary settlements there may have been prohibitions against wine production and its consumption (Fuks et al., 2020). The same was true for the consumption of pork, which is absent in archaeozoological records of most Early Islamic-period Negev sites (Marom et al., 2019).

Mitzpe Shivta represents a largely unstudied archaeological archive, offering valuable insights into the agricultural, economic and social roles of monasteries during the Byzantine– Early Islamic transition and beyond. As a rural monastery it can provide new perspectives on this unexplored type of settlement, and due to its proximity to Shivta, it may be linked to chronological developments in larger agricultural villages in the Negev. In our project we employed a multidisciplinary research protocol to conduct excavations and sampling in different areas of the site, focusing on rock-cut rooms and connected stone-built compounds. Our goals were to reconstruct the cultural history of the site by clarifying its stratigraphy and dating its various archaeological contexts. In this article we outline the current knowledge of the site's chronology by presenting the new radiocarbon data from our excavations. Since pottery finds are not particularly frequent at Mitzpe Shivta, the establishment of an initial 14C chronology is of great importance for understanding the site's history.

Excavations and sampling at Mitzpe Shivta took place during two campaigns in the autumns of 2022 and 2023, with the aim of characterizing for the first time the settlement’s history, chronology and function in terms of monasticism, pilgrimage and local economy. Two investigations targeted the rock-cut spaces typical of the site (Areas A and B), while two others focused on buildings made of local marl limestone and flintstone that are situated in front of these spaces (Areas C and F; Fig. 3). These dual architectural compounds, featuring rock-cut spaces and standing masonry, bear typological similarities to those discovered at the Byzantine–Early Islamic settlement of Avdat. Previous studies at Avdat have associated these structures with monastic establishments and their activities, including animal husbandry, wine production and pilgrimage economy (Bucking and Erickson-Gini, 2020; Bucking et al., 2022). Stone-built rooms in Areas D and E, adjacent to Area F, are connected to the rock-cut rooms in Area A. So far, these have been documented only by surface surveying. Their layout and the visible masonry and plaster cladding suggest an economic/industrial function, possibly a wine press.

We divided the excavation areas into 1 sq m units, which were explored in 10 cm deep spits, measured using an RTK GNSS receiver with LT 1 cm precision for mapping. All excavated sediments were dry sieved through a 5 mm mesh to retrieve small artifacts and biological remains. Sediment samples were collected for flotation of botanical remains, as additional samples, for chronometric determinations (14C) and geoarchaeological analysis. In addition, we took wall plaster samples to date charcoal inclusions and analyze mineralogically the plaster's composition.

Table 1 presents the samples collected for radiocarbon dating, including their material, condition and archaeological context. These comprise an uncharred straw fragment from Area A, an uncharred grape seed and a charcoal fragment from Area B, an uncharred straw fragment from the plaster of the outer wall of the rock-cut room in Area C and selected charcoal samples from various stratigraphic layers in Area F. The samples were sent to the Poznan Radiocarbon Laboratory. The complete analytical procedure for organic samples such as charcoal and other plant remains, including chemical pre-treatment using the three-step AAA method (acid-alkali-acid), combustion of the sample and AMS measurement, is described on the laboratory's website (https://radiocarbon.pl/en/sample-preparation/). The 14C age was calibrated using the OxCal program, version 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009) with the newest version of 14C calibration curve IntCal20 (Reimer et al., 2020).

Area A (Fig. 4) comprises a unit of three contiguous rock-cut rooms on the lower, northern terrace of the site. The rooms are hewn out of the soft local marl limestone of a plateau, on top of which are the church and other buildings. Intensive quarrying traces that cover the walls of the rooms illustrate this process (Fig. 4d). In front of them and on the same level, remains of a stone building are partly preserved. Immediately above the rock-cut rooms is a building made of massive ashlars that corresponds to the layout of the lower stone building (Fig. 3b, c).

Our main point of interest was the first of the three rooms, which is presently accessible from the north through a rock-cut entrance 0.6 m high and 2.5 m wide (Fig. 3b). The room's plan (Fig. 3c) is a perfect square (5.8 x 5.8 m). A small niche was carved out into the rock in the southern wall of the room (Fig. 4b), and in the northwestern corner there is a low, roughly worked passage to the second room of the complex. A cross was carved on the eastern wall (Fig. 4d); its arms narrow toward the center, classifying it as a Christian cross /Jaffee. The Greek letter P (Rho) on the cross's right side may indicate that this is a variant of a Christogram. The only other decorated walls are in one of the rooms adjacent to the first room, where the wall plaster bears remnants of red ink (Fig. 4e).

During our survey of the room, we found a 1.0 x 1.3 m looting trench adjacent to the rock facade, immediately below the cross (Fig. 4c). Such forms of looting near inscriptions, crosses or petroglyphs—commonly associated with markers for buried treasures—are known also at other sites in the Negev region (Lior Schwimer, pers. comm.). We found the trench with collapsed sections, filled with sediment and remains of animal dung, plants and modern garbage, including the scraps of a newspaper from 1973, when the site was already within the boundaries of the training ground of the neighboring Shivta Base.

An initial cleanup of the trench indicated a good preservation of organic material with charcoal suitable for radiocarbon dating and micro- geoarchaeology. We consequently cleaned the entire trench out, from the surface down to bedrock, to a depth of 0.9 m. Following this, we extended the area of the trench by 0.5 m to the south and conducted an excavation in 10 cm spits. The excavation of the upper three layers (L.1001–1003) revealed an accumulation of light to dark ashy soil with inclusions of limestone, twigs, fresh livestock dung pellets and modern remains. In addition, in all three layers we found few pottery fragments dating to the Byzantine period (bag-shaped jars), as well as animal bones and remains of textiles. In the following layer (L.1004) we perceived a significant change in the nature of the sediment, with straw and animal dung compacted to about 5 cm thick of very solid matrix. This horizon was again followed by a layer (L.1005) of loose gray-brown ash with inclusions of dung pellets and animal bones, with pottery dated to the British Mandate period. We found a particularly fine brown sediment in the lower three layers (L.1007–1009), above the bedrock, interspersed with animal bones and Early Islamic cooking ware. We also found a large worked wooden fragment in L.1008—probably part of a piece of furniture or a peg. The rock-cut floor at the bottom of the trench was mostly even and had probably been hewn similarly as the walls of the room to create a level living floor (Fig. 4c). A straw fragment from just above the bedrock was sent for radiocarbon dating. The calibrated date falls between 1484 calCE and 1644 calCE, within the Ottoman period (Tab. 1, Fig. 5).

Area A yielded several identified animal bones that were distributed evenly in the section. These include long bones and teeth of both adult and juvenile sheep or goats, a burnt pelvis and a molar tooth of an adult camel. Some of the bones bear evidence of carnivore gnawing.

Area B (Fig. 6a), on the eastern slope of the site, presents a roughly oval structure partly carved into the local rock and partly built of thin bricks (Fig. 6b). The structure's western side had been somewhat deformed by the pressure of natural rocks that had collapsed, sediment and architectural fragments—possibly the result of seismic activity. Some of the debris filled the structure's interior. We uncovered the remains of a floor made of compacted clay and lime at the elevation of the base of the brick structure. It was only partially preserved, near the walls of the oval structure, and its center had collapsed (Fig. 6d).