Mezad Yeruham

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Mezad Yeruham, Mezad Yeroham | Hebrew | |

| Qasr Rekhmeh | Arabic | |

| Wády Rakhmeh | Arabic |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 28 June 2025

- sources: Tal et al. (2025)

Originally surveyed by Avraham Negev in the early 1960s, Meẓad Yeroḥam was then identified as a Nabataean–Roman way-station or caravanserai. Subsequent scholarship has questioned this view. A 1980 preliminary report by Negev described an architectural complex without systematic excavation, and the site remained relatively unexamined until 1993.

That year, a salvage excavation led by Rafi Bernstein and Oren Tal took place in advance of a planned water pipeline. This brief campaign revealed significant remains from the Late Roman to Early Islamic periods and was followed by a larger-scale excavation in 2000. The 2000 excavation uncovered an extensive settlement consisting of at least six major buildings, distributed over distinct sectors labeled Area A (northeastern slope) and Area B (western slope).

Based on material finds, architectural features, and stratified deposits, the site is now understood as a rural settlement with a strong military character during the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. It may have functioned as a local garrison post within a broader defense or administrative network in the Negev. The discoveries at Meẓad Yeroḥam offer insight into settlement continuity, collapse, and seismic rebuilding from the 4th to 8th centuries CE.

Mezad Yeroham, west of the Sede Boqer-Yeroham road, about 1.5 km (1 mi.) southwest of the development town of Yeroham (map reference 1408.0438), is a site occupying a total area of some 25 a. It is situated on Neogene hills covered with limestone hamada, between the two branches of Nahal Shu'alim, near Lake Yeroham. The site was first surveyed in 1870 by E. H. Palmer, who reported the remains of a town buried under so much alluvium it was almost invisible on the surface. N. Glueck realized the importance of the site in his 1954 survey of the Negev. He called it Qasr Rahme. He discovered a tombstone here on which the name "Alexandros" was incised in Greek. The site was surveyed in 1965 and its extent determined by the southern team of the Archaeological Survey of Israel, directed by R. Cohen. Cohen later (1966-1967) excavated here on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. The excavations were necessitated by the plan to turn the area around Lake Yeroham into a park. The excavations were concentrated in four areas (A-D), in which three levels of occupation were identified (strata 1-3).

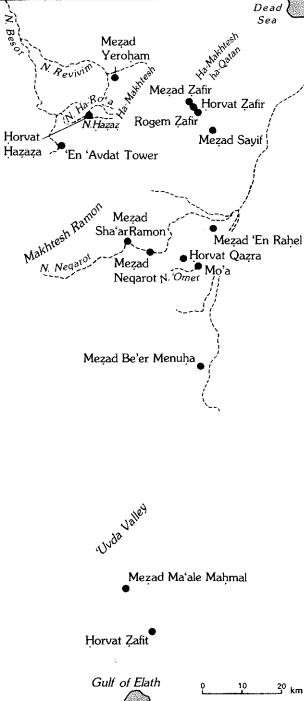

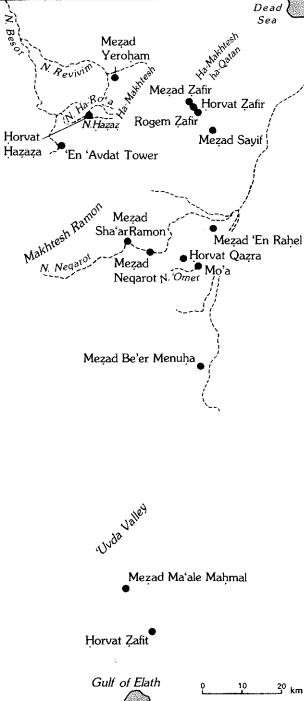

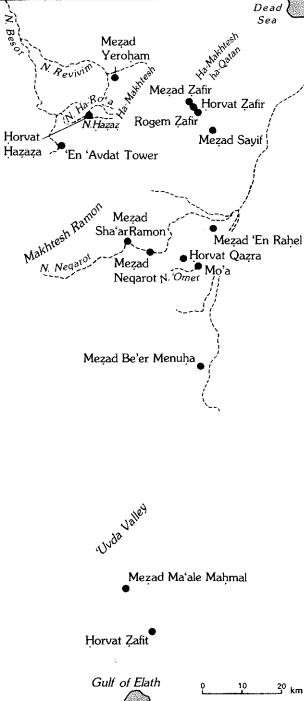

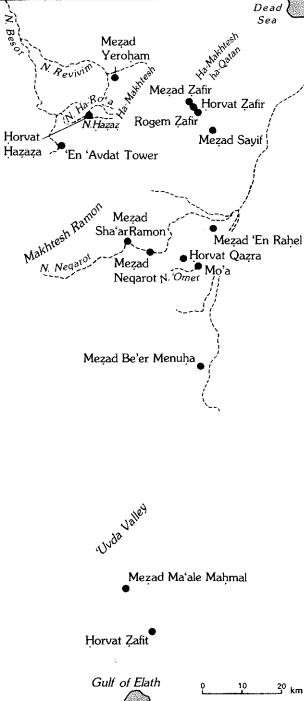

- Location Map from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Map of the main Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine sites in the Negev Hills

Map of the main Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine sites in the Negev Hills

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 1.1 Location Map from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 1.2 Terrain model

(DEM) of Meẓad Yeroḥam from Tal et al. (2025)

- Location Map from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Map of the main Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine sites in the Negev Hills

Map of the main Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine sites in the Negev Hills

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 1.1 Location Map from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 1.2 Terrain model

(DEM) of Meẓad Yeroḥam from Tal et al. (2025)

- Aerial View of Mezad Yeroham

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Mezad Yeroham: aerial view of the site and vicinity.

Mezad Yeroham: aerial view of the site and vicinity.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 1.3 Aerial photograph

of the site as taken after the 1966–1967 excavations from Tal et al. (2025)

- Mezad Yeruham in Google Earth

- Mezad Yeruham on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2.1 Site plan from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.2 Aerial photograph

with excavation areas from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.1 Site plan from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.2 Aerial photograph

with excavation areas from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.3 Photo of Area A from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.4 Area A, area plan from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.3 Photo of Area A from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.4 Area A, area plan from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.18 Photo of Area B

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.17 Area B

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.19 Area B, Buildings I–VI from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.20 Area B, plan of Building I from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.30a Area B, plan of Building II from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.57 Area B, plan of Building III from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.58 Area B, Building III

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.63a Area B, plan of Building IV from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.77 Area B, plan of Building V from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.102a Area B, plan of Building VI from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.18 Photo of Area B

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.17 Area B

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.19 Area B, Buildings I–VI from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.20 Area B, plan of Building I from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.30a Area B, plan of Building II from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.57 Area B, plan of Building III from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.58 Area B, Building III

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.63a Area B, plan of Building IV from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.77 Area B, plan of Building V from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.102a Area B, plan of Building VI from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.9 Fallen Arch in Area A from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.13 base (plinth)

and colonnette in Area A Room 2 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.37 colonette

and capital in Area B, Building II, Room 21 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.44 Fallen arch stones

in Area B, Building II, Room 24 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.45 Fallen arch stones

in Area B, Building II, Room 24 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.47 Through-going crack

in Area B, Building II, Room 40 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.74 Area B, Building IV,

Room 60, pilaster from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.82 Broken Ashlar in

Area B, Building V, from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.86 Tilted Wall

(possibly due to soil pressure) in Area B, Building V, Chamber 99 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.89 Broken lintel in

Area B, Building V, Room 95 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.107 Collapse in Area

B, Building VI, Locus 504 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.108 Broken lintel

from Area B, Building VI, Room 120 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.115 Area C, Room 155

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.116 Area C, Room 155

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.124 Fallen arches in

Area C, Room 186 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.9 Fallen Arch in Area A from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.13 base (plinth)

and colonnette in Area A Room 2 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.37 colonette

and capital in Area B, Building II, Room 21 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.44 Fallen arch stones

in Area B, Building II, Room 24 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.45 Fallen arch stones

in Area B, Building II, Room 24 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.47 Through-going crack

in Area B, Building II, Room 40 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.74 Area B, Building IV,

Room 60, pilaster from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.82 Broken Ashlar in

Area B, Building V, from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.86 Tilted Wall

(possibly due to soil pressure) in Area B, Building V, Chamber 99 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.89 Broken lintel in

Area B, Building V, Room 95 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.107 Collapse in Area

B, Building VI, Locus 504 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.108 Broken lintel

from Area B, Building VI, Room 120 from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.115 Area C, Room 155

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.116 Area C, Room 155

from Tal et al. (2025)

- Fig. 2.124 Fallen arches in

Area C, Room 186 from Tal et al. (2025)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 27 June 2025

- from Bernsetin et al. (2025) and Tal et al. (2025)

The earliest phase is represented by a prepared earthen floor laid directly atop bedrock in the western room of the structure. It was associated with the original construction of the fort, likely in the Late Roman or early Byzantine period.

Above this was a thick fill layer consisting of collapse debris, which included roof tiles, wooden beams, plaster, and broken pottery. This layer sealed the earlier floor and is interpreted as a destruction layer. Its composition and position suggest a sudden catastrophic event, consistent with seismic collapse. The ceramic material embedded in this layer includes 7th-century CE forms, anchoring its date to the late Byzantine or early Islamic period.

Capping the destruction debris was a thin accumulation of windblown material and occasional animal bones. There is no evidence of reconstruction or reuse, indicating that the site was permanently abandoned after the collapse.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 27 June 2025

- from Bernsetin et al. (2025) and Tal et al. (2025)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Post-Abandonment | 7th century CE onward | Windblown fill and animal remains overlying collapse debris; no evidence of rebuilding or reuse. |

| II | Late Byzantine / Early Islamic | 7th century CE | Thick collapse layer with roof tiles, ashlars, and 7th-century ceramics. Indicates sudden destruction, possibly seismic. |

| I | Late Roman / Early Byzantine | 4th–6th century CE | Prepared earthen floor atop bedrock; original construction phase of the caravanserai structure. |

| Stratum | Period | Dates | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Byzantine | 5th-6th centuries CE | The highest point in the development of the settlement at Mezad Yeroham was in the Byzantine period (fifth-sixth centuries). Buildings were found in areas A, B, and D, indicating that the Byzantine settlement occupied the northern part of the site. Some of the agricultural terraces along Nahal Shu'alim, north and northeast of the settlement, should probably be assigned to the same period. |

| 2 | Late Roman | 3rd-4th centuries CE | Remains from the Late Roman period were exposed in areas B and C. They comprised two levels of occupation. Stratum 2B was assigned to the second and third centuries, beginning under Hadrian (117- 138) and probably reaching its peak under Commodus (180-192). Stratum 2A was assigned to the third and fourth centuries - from the time of Severus (193-211) to its peak development during the reign of Constantine the Great (324-337). A stratigraphic sounding, going down to bedrock, was carried out in the southern part of area B, under the remains of the Byzantine structure VI (stratum 1 ), over an area of some 20 by 10m. It unearthed remains of a Roman structure (XV) built of ashlars. Two building stages could be identified (strata 2A and 2B). In the northern part of area C, the excavators cleared ten rooms of a building (XVI). Here, too, there were two discernible building stages (strata 2A and 2B). |

| 3 | Nabatean | beginning of 1st century CE | The Nabatean settlement at Mead Yeroham

(stratum 3B) should probably be dated to the beginning of the first century, in

the reign of Aretas IV (9 BCE-40 CE).

Its earliest stage was probably as a road

station during the first half of the first

century BCE (stratum 3B), remains of

which were found in areas B and C. In

time, a permanent settlement developed here. At the height of its prosperity (stratum 3A), it was built of ashlars.

Its remains were unearthed in areas B

and C. Stratum 3A, most of which was

found in area B, should be dated to the

second half of the first century CE,

perhaps to the reign of Rabbel II

(70-106). A stratigraphic sounding was carried out in the southern part of area B. Among the finds were the remains of a Nabatean structure (XX) that consisted of several rooms. Two building stages were discernible (strata 3A and 3B). The finds on the floors of the rooms included painted Nabatean bowls and coins of Aretas IV (stratum 3B) and Rabbel II (stratum 3A). Also worthy of mention was an altar shaped ivory charm. A building containing a large room (9.50 by 8.50 m) was cleared in the southern part of area C (structure XXI). In the room were five pillars. To its north and south were small rooms (3.5 by 2.9 m). Here, again, two levels of occupation were identified (strata 3A and 3B). |

- from Cohen (1968)

The site occupies approximately 100 dunams and, as E.H. Palmer already pointed out in 1870, the remains of this installation “so scattered and so covered by the earth, that they appear above ground ". In 1953, Prof. Nelson Glueck identified a large Nabataean installation and the objects found on the surface depicted the Greek name of Alexander. While surveying the site in 1965, the Israeli team came to the conclusion that this installation understood a several mounds representing individual buildings which were part of a fort.

The excavations were mainly focused on two of these Hills. On the first northern hill, we uncovered a construction covering more than 800 m2. It consisted of three blocks of dwellings comprising, in total, twelve rooms connected by a courtyard central. The walls were preserved to a height of 1.80 m. The objects found on the floor of the rooms date from the 5th-6th centuries AD. and include Byzantine pots, lamps, jars and coins.

On the central hill, the highest on the site, we have partially cleared four buildings. A street, 2.70 m wide, divides this together in two sectors east and west.

In the western sector, a building, which covers more than 500 m2 consists of eighteen rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The walls were preserved at a height of 2-3 m. A lintel, decorated with rosettes, was among the rubble, near the entrance of one of the rooms. Objects found on the floors of the rooms go back in the 5th-6th centuries AD and include many ceramic objects: lamps, jugs, pots, jugs, jars and small decorated bowls. Two Greek ostraca written in black ink are particularly interesting.

Two similar buildings, covering more than 950 m3, were cleared in the eastern sector. There, too, ceramics and coins indicate the 5th-6th centuries AD. A lintel decorated with a cross is of special interest.

In the southern part of the site, the remains of a Nabataean building were excavated. Ceramic objects collected from the floors of the rooms and court include many beautiful Nabataean sherds decorated and stamped.

Mesad Yeruham appears to have served as a guard post on the ancient Avdat (Oboda) - Mamshit (Kurnub) trade route and its existence is linked to the history of the Nabataeans and the great Roman-Byzantine road in the Negev.

- from Tal et al. (2025:3)

The crystallization of Meẓad Yeroḥam as a continuously occupied site may likely have occurred in the context of the Roman annexation of the Nabatean kingdom and its transformation into the Roman province of Arabia in 106 CE. The annexation was carried out during the reign of Trajan and the death of the last king of the Nabatean kingdom Rabbel II Soter (70–106 CE) may have prompted the official decision of Rome (Bowersock 1983: 70–89). The reason for this annexation may also have been related to the desire of the Roman ruler to limit the potential threat to the borders and improve the empire’s entirety (Erickson-Gini 2010: 47). In addition, benefit from control over the production and trade of aromatics along the Incense Road may have also been a consideration (Isaac 1992: 385).

The previously buffer-zoned Negev, after being fully integrated into the Roman Empire, formed part of the Provincia Arabia (Di Segni 2018). The administrative and military capital was Bostra, re-founded as Nova Traiana (Parker 1986; as also attested on coins RPC III: s.v. Bostra = ΝΕΑϹ ΤΡΑΙΑΝΗϹ ΒOϹΤΡΑϹ [https:// rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/search/browse?q=Bostra]). Major and secondary administrative centers in the Negev were now divided among several urban-oriented settlements. Elusa (Ḥalutza) seems to have been the main administrative capital in the region in both Roman and Byzantine periods, whereas other large settlements, such as Oboda (‘Avdat), located along the Incense Road, and Mampsis (Mamshit), located on a major road leading from the Dead Sea and Transjordan, had a secondary administrative character. Meẓad Yeroḥam, being located between these two settlements, was likely affected by their status during the Roman and Byzantine periods throughout its existence.

The Legio III Cyrenaica controlled the Provincia Arabia between 106 and the mid-3rd century CE. It was based in Bostra but military troops also occupied settlements in the Negev as can be deduced from epigraphic evidence and Roman military tombstones (Mampsis) (Negev 1981). These troops’ activities ensured local security and road maintenance (Erickson-Gini 2010: 50) and, in fact, ensured the continuity of the international incense trade network throughout the Negev. Recently published milestones, including one that gives the distance of 40 miles from Elusa assigned to the days of emperor Publius Helvius Pertinax (193 CE) (Ben David and Isaac 2020: 240–241, IMC 706), as well as others dated to the days of Septimius Severus (200 CE; Ben David and Isaac 2020: 238–240, IMC 705), provide more evidence for this maintenance. A recently published milestone along the Oboda–Meẓad Yeroḥam road indicates the existence of a newly discovered branch of a Roman road between Oboda and Mampsis by way of Meẓad Ḥaluqim–Meẓad Yeroḥam–Meẓad Ḥorvat Bor (Ben David 2019: 139–141, Fig. 7).

The 3rd century CE likely saw an economic crisis that coincided with the disappearance of the Legio III Cyrenaica from the region sometime in the first half of the 3rd century and the probable decrease (or cessation) of the international incense trade network at sites along (and nearby) the Incense Road. This crisis is also confirmed by the absence of coins from the Transjordanian mints dated later than the reign of Elagabalus (218–222 CE), as well as a break in the ceramic tradition, concerning both locally produced and imported vessels (Erickson-Gini 2010: 60–63).

The reforms of Diocletian likely affected Palestine and, more specifically, the Negev as the Persian (Sasanian) threat had to be countered militarily. The so-called Limes Palaestinae was characterized by military strongholds along the Roman road network. In addition, the Legio X Fretensis was transferred from Jerusalem to the harbor economy. Around the same period, the Nabatean inscriptions in the Aramaic alphabet stopped being used in favor of Greek script, with Greek language becoming the province’s official language (for the latest Nabataean inscription in Aramaic script, whose date is 4th–5th century CE, see Erickson-Gini 2010: 189, Fig. 7.5).

The increase in the number of settlements in the Byzantine- period Negev is likely the result of demographic growth after the stabilization of the political (by militarizing the region) and economic situation in the 4th century CE. This imperial effort was likely connected to security maintenance across the long-distance trade routes of the empire connecting regions in Asia and Africa to the Mediterranean. The agrarian nature of many of the (mostly surveyed) Roman-period sites suggest an increase in cultivated agricultural plots by the Early Byzantine period and the cultivation of agricultural species previously unfamiliar in the region (Wacławik 2023: 210–211). It therefore stands to reason that while imperial effort was witnessed in the military sphere, settlements of the Negev were to a large extent based on self-organized economy (Erickson-Gini 2010); individuals within the Negev settlements organized their communal behavior among themselves rather than through external intervention.

The increase in the number of settlement sites of civilian and military character, as well as the tremendous construction of churches (and some monasteries) throughout the Negev (Figueras 2013) relates to demographic growth likely connected to the political stability at a time which allowed the absorption of newcomers to the region. This absorption was not only of active and ex-Roman military personnel, but also civilians, clergy, and monks found the province’s militarized and Christianized character appealing. To this may be added the international movement of pilgrimage, be it to Saint Katherine’s monastery in southern Sinai (Figueras 1995; Whiting 2020) or to a more localized cult such as St. Theodore at Oboda (Erickson-Gini 2022). This brought a plethora of commercial activities to the region, with Meẓad Yeroḥam taking an active role in this movement within the context of its Byzantine occupation, likely providing service to merchant caravans and pilgrims.

The second half of the 6th century CE saw the abandonment of some Negev settlements (as evidenced by coins, i.e. , Mampsis and Meẓad Yeroḥam for the sake of the current introduction). The decline of the flourishing habitation of the Late Byzantine Negev is a much-debated issue and it is addressed in some detail in the context of Meẓad Yeroḥam in the summary of this monograph. Some scholars relate it to the outbreak of the Justinian Plague (541–542 CE) as one of the principal causes of this decline. Earthquakes and droughts were likely an additional reason. Other scholars however, find the treaty of Eternal Peace (between the Byzantines [Justin I] and Sasanians [Khosrow I/Anushirvan], 532 CE) and its aftermath, when the military personnel was no longer financed by the empire, as a more immediate reason for this process. This eventually paved the way for military campaigns of the Sasanian rulers in the early 7th century CE, followed by the Muslim-Arab conquest of the 630s which ended Byzantine rule and opened a new era in the history of the Negev.

- from Tal et al. (2025:6)

the remains of a very large ancient cemetery, whose burial stones have served as a convenient source of material for modern road builders [...] among the remnants of ancient grave markers, we found an intact one with the name “Alexandros” on it written in Greek letters (Glueck 1955: 8) (see Chapter 4).In 1966 the site was surveyed by the southern team of the Archaeological Survey of Israel, led by Cohen (the then Israel Department of Antiquities and Museum Southern District Archaeologist). During this time an ancient cemetery was (re)documented (as had been discovered about a decade earlier by Glueck east of the site), next to the eastern edges of the Yeroḥam—Sede Boqer road (No. 204). It included at least four tombs that were beyond the southeastern edge of the site. The tombs were found some 3 m apart, built of well-dressed soft limestone and covered by large stone slabs and are briefly described in an archival file (Chapter 4).

Excavations at the site began in September 1966 and lasted until April 1967 in the framework of a public park development in the area of the Yeroḥam reservoir (Cohen 1967: 1; Permit No. A-96/1966) (Fig. 1.3). An archival letter from April 1966 suggests that the initiative came from Cohen after inspecting the public park development plans and being aware of the importance of the site’s Roman/Nabatean archaeological remains in its agricultural infrastructure (the existence of terraces and dams). The idea was to have a protected archaeological site within the borders of the public park.

The November-December 1993 season at the site apparently concentrated on Cohen’s excavation Area B’s southwestern part (Permit No. A-2018/1993); unlike the 1966 season and the 2000 season, hardly any archival records were submitted or located (apart from the excavation logbook and plans). There are records of finds recovered from the 1993 season, among them “organic rope, two glass beads, eight coins, two jewels, an ornamented bone comb, an ostracon, a box of metal objects and 37 pottery boxes (Cohen 2021), which we managed to locate in part.

The June 2000 season, directed by Ya‘aqov Baumgarten, lasted intermittently until September of that year in the framework of the Yeroḥam public park development and in order to expedite conservation works (Permit No. A-3241/2000). Excavations were also aimed at answering questions on the nature of the remains of Area B’s northwestern and southwestern parts, where excavations were concentrated, as these parts had only partially been excavated in earlier seasons.

Since the 2000 season the site was left undeveloped. It is an appendage of the public park, but present-day accessibility to the site is easier from the Yeroḥam—Sede Boqer road rather than the public park area. The site itself is rarely visited, being less known than the “Nabataean Towns of the Negev” and less attractive than the isolated road stations and/or fortresses along the Roman road system of the Negev.

As noted earlier, the site has been mentioned in literature since the late 19th century, following excavations and surveys that had been conducted in the region of Meẓad Yeroḥam. The most comprehensive survey was directed by Nahlieli in 1978 in the framework of the Archaeological Survey of Israel (Map 177 – Yeruham). Oddly enough, this survey ignores the map’s principal site, Meẓad Yeroḥam, and documents meager remains dated to the Middle Bronze Age, Early Bronze Age and Iron Age at a number of sites in the surveyed map area, as well as seven Byzantine-period sites whose remains were assigned to farmsteads, dams, agricultural terraces, retaining walls, rock-hewn pits and tombs in the area to the north of the site and the modern town. Two Byzantine sites whose occupation likely continued in the Early Islamic period are documented there as well (Nahlieli and Veinberger 2015).

Relatively small-scale excavations that postdate the publication of the Yeruham survey map (177) may be mentioned here as well. The southeastern periphery (some 1–2 km in distance) was included in a development survey carried out in 2017, where 121 archaeological features were documented and 114 agricultural terrace walls were identified; one of the terrace walls was excavated, another field wall was cleaned, and a nearby field tower was identified. The documented and excavated terraces belonged to an agricultural system that captured the runoff water and the alluvium carried with it, creating conveniently level plots of rich farmland whose proximity to Meẓad Yeroḥam suggests they were part of its agricultural system during the Byzantine period as may also be learned from their construction method (Rasiuk 2019). A trial excavation was conducted in 2019 south of the town of Yeroḥam and northeast of Naḥal Shu‘alim, about 1 km to the southeast of Meẓad Yeroḥam. The excavation unearthed a single oval building, eight agricultural terrace walls and 12 stone heaps (Sapir 2021). Some of these remains may be assigned to Meẓad Yeroḥam’s Byzantine period agricultural hinterland based on similarity in construction methods to other such installations. Another excavation was conducted in 2020 unearthing tumuli built directly on a rocky outcrop each with a built burial cell, but these likely predate the period of Meẓad Yeroḥam’s occupation (Sapir 2023). Two undatable agricultural terraces in the Yeroḥam Park area (Paran 2007) may also be mentioned in this context as they are omitted from the map.

Given the intensive work of the Negev Emergency Survey which was conducted in the contexts of the peace agreement with Egypt that led to the redeployment of the Israel Defense Forces, the Israel Archaeological Survey Society carried out one of its most extensive and important surveys at the time in Israel for about a decade from 1978 to 1988 and for decades thereafter.

Many of the survey maps around that of Yeroḥam are the result of this endeavor, and given the fact that most of them were published during the last decade, our understanding of the settlement dynamics in the area that surrounded the site during the Nabatean/Roman and Byzantine periods is relatively good (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Archaeological Survey of Israel maps around the Map of Yeroḥam (Yeruḥam)

- Masaf Negev – 160

- Yeruham Ridge – 173

- Dimona – 174

- Nahal Revivim – 164

- Yeruham – 177

- Har Zayyad – 178

- Sede Boqer (East) – 168 (Cohen 1981)

- Hamekhtesh Hagadol – 181 (yet unpublished)

- Oron – 182 (yet unpublished)

The survey map to the northwest of Yeroḥam is that of Masaf Negev (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2014), whose surveyed area is divided between the northern Negev Highlands (most of the surveyed region) and the Negev Foothills, without any major site dated to the Classical periods. However, there are no less than five sites of the Nabatean/Early Roman period whose remains include square buildings arranged around a central courtyard (e.g., Site No. 36 [Naḥal Zaḥal 13]; road station?), agricultural terraces and water cisterns; nine sites of the Late Roman period, whose remains include dams and agricultural terraces; and no less than 62 sites of the Byzantine period, whose remains include farmsteads, encampment sites (where there is sherd scatter and buildings or the bases of tents whose walls were built of two rows of fieldstones with gravel filled in between) and water cisterns. It may be added that the Roman period sites continued (in most cases) to be occupied in the Byzantine period; while only three of the Byzantine period sites show occupation in the Early Islamic period.

The survey map to the west of Yeroḥam is that of Naḥal Revivim (Baumgarten and Eldar-Nir 2014), whose surveyed area may represent the boundary between the central and the northern Negev Highlands. There are no major sites dated to the Classical periods, and only one site of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic?) period, whose remains include round and square buildings next to three round courtyards and an animal pen (Site No. 204 [Ramat Boqer 10]; a road station?); 13 sites are attributed to the Roman period, with three to the Early Roman period, four to the Late Roman period and six other sites that could not be ascribed to a specific sub-phase of the Roman period; and no less than 62 sites of the Byzantine period whose remains include farmsteads, animal pens/large courtyards, enclosure walls (of cultivation plots) and agricultural terraces, and water systems (cisterns and dams). It may be added that the Roman period sites continued (in most cases) to be occupied in the Byzantine period; half of the Byzantine period sites were found to be single-period sites; four of the Byzantine period sites show occupation in the Early Islamic period.

The survey map to the southwest of Yeroḥam is that of Sede Boqer (East) (Cohen 1981), whose surveyed area is located in the southern part of the northern Negev Highlands, without any major site dated to the Classical periods. The underrepresented Persian period occupation in the Negev highland is attested at one site (Site No. 65). There are six sites of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period – with three of them preserving architectural remains – Ḥorvat Ḥaẓaẓa (Site No. 83) stands out among them given its impressive Nabatean/ Roman remains and the fact that it may well have been connected to the agricultural hinterland near it with terraces and water cisterns (Site Nos. 99, 101). The three sites of the Roman period are basically adjacent to the Nabatean sites whereas the 45 sites of the Byzantine period are mostly agricultural oriented and divided among isolated buildings, animal pens and water installations – in areas related to the agricultural hinterland of the larger settlements in the area such as Oboda (‘Avdat). Many of the eight sites that show Islamic period occupation have Byzantine period occupation as well and demonstrate the very partial habitation of the Negev Highlands at the time.

The survey map to the north of Yeroḥam is that of Yeroḥam Ridge (Rekhes Yeroḥam) (Eldar-Nir and Traubman 2015), whose surveyed area is bounded on the north by Mount Nokdim, on the east by the Dimona Mountains, on the south and southeast by the Yeroḥam Plain and the site of Meẓad Yeroḥam, on the southwest by the Kaskasim Mountains and on the west by Mount Tzavoa‘, without any major site dated to the Classical periods, and three sites of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period with either later or earlier occupation; six sites of the Roman period; and 53 sites of the Byzantine period. Twenty-three seem to have been founded during this period while for the remainder, their occupation continued or the site was resettled anew after a gap in its occupation. In four of the seven recorded Early Islamic period sites, their occupation continued from the Byzantine period, while the other three were either inhabited anew under Islamic (2) rule or resettled anew after being occupied during the Middle Bronze Age (1).

Additional information comes from more recent work. Northeast of the modern town of Yeroḥam, the Naḥal Avnon area was surveyed in 2011 in the context of railroad construction between Yeroḥam and Dimona. In this survey, some 18 sites with archaeological remains were identified along Naḥal Avnon, mainly farming terraces, structures and walls (Shmueli, Aladjem and Radashkovsky 2012). Additional works in the surveyed area took place in 2020, trial excavations unearthing segments of field walls that were probably related to agricultural systems (Davis 2021; 2024). In 2018 a salvage excavation was conducted at the sites of the Yeroḥam Ridge and Naḥal ‘Eẓem prior to regularizing the status of the Qasr es-Sir Bedouin community. Field (terrace) walls were found whose functions were diverse: delimiting cultivation beds and stabilizing the soil and marking the boundaries of cultivated plots. The wadi-bed terrace walls were built to level the colluvial soil in the wadi channel and to slow and divert the water flow during flooding. The construction methods of the field and terrace walls may well be attributed to the Byzantine period (Mamalya 2021); “a watchman’s hut” without datable artifacts in the area (Paran and Sonntag 2012) may also be assigned to this period.

The survey map to the northeast of Yeroḥam is that of Dimona (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2014), whose surveyed area is divided between two phytogeographic regions in the heart of the central Negev Highlands – the Irano-Turanian region and the Saharo-Arabian region. The map does not include a major site dated to the Classical periods; with only one site of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period; five sites of the Roman period; and forty-six sites of the Byzantine period, of which thirty-four were single period sites. Among the Byzantine period sites are farmsteads, dams, animal pens and other agricultural installations – remains whose character indicates the development of established agricultural activity in the region in the Byzantine period, as seen also in neighboring survey maps. Only two sites on the map show Islamic occupation; one of them also dates to the Byzantine period while the other to the Iron Age.

The survey map to the east of Yeroḥam is that of Har Ẓayyad (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2015), whose surveyed area is in the northeastern part of the Negev Highlands, ca. 2 kilometers south of the town of Dimona. The sandy plain of Mishor Rotem and Har Rotem are situated at the map’s northeastern corner. The map includes a major site dated to the Classical periods – that is Mampsis (Mamshit – Kurnub) (Site No. 16), whose occupation lasted from the Nabatean period until the Early Islamic period and whose architectural remains include a town wall and gate, a tower, a manor house and residential buildings, a bathhouse, caravanserai and churches, as well as civilian and military cemeteries. Two additional sites, one single (Nabatean) and the other (Nabatean/Roman) brings the total number of Nabatean/Roman period sites on the survey map area to three; as in other survey maps of the Negev Highlands, the number of Byzantine period sites is the highest; 19 sites are recorded on the current one. Their architectural remains include buildings, courtyards, animal pens and a few water installations (a dam and two cisterns), as the agricultural potential of the Mampsis periphery was limited and the economy relied more on trade caravans. Early Islamic occupation in the map area is only attested in Mampsis.

The survey maps to the south (Hamekhtesh Hagadol) and southeast (Oron) of Yeroḥam are yet unpublished in detail; they are briefly mentioned in part in a manner that suggests a somewhat similar picture to their surrounding maps (Eldar 1982).

In sum, the survey map of Yeroḥam and those that surround it suggest somewhat similar settlement dynamics from the second half of the first millennium BCE to the first millennium CE. The near break of habitation after the Iron Age, in which hardly any settlement of the area during the Persian and Early Hellenistic periods is recorded, agrees with the few settlements known from this period in the entire region of the Negev. As stated above, the Late Hellenistic (or early Nabatean) settlements recorded are difficult to assess based on the surveys carried out and the published material, as the painted Nabatean pottery that assisted the surveyors to identify Nabatean settlements is normally dated to the Roman period. Early Nabatean settlements in the area discussed above seem to be numbered and it is clear that the later Nabatean settlements of Early Roman date were much more prevalent. As the Negev’s Imperial Roman occupation began in the early 2nd century CE, more settlements were established but the total number of all these Hellenistic and Roman settlements seems to be marginal when compared to the numerous Byzantine period sites of the Negev whose raison d’être is related to the Christianization of Palaestina Tertia. The sharp decrease in the number of Early Islamic sites should be understood against the lack of imperial interest of the ruling Islamic authorities.

- from Tal et al. (2025:23)

Building I is located in the western part of the area, possibly revealing the eastern wing of a more extensive building (Figs. 2.18 and 2.19). It is flanked by Building II on its east. Its excavation area was enlarged in the 2000 season of excavations. East of Building II there is an alley (44) separating Building II from Building III; the length of the alley is some 18.5 m. Building III is located to the east of this alley; Building IV is the easternmost building excavated in the area and, like other buildings, it consists of a central courtyard that has four different wings around it. Building V is rather similar to Building II in that the excavations uncovered only part of a wider building. The southernmost building in the area is Building VI, which also consists of a central courtyard around which various wings were built. The excavation of Building VI was also enlarged in the 2000 season.

This building is the westernmost building excavated in the area, adjacent to Building II on its east. It was only partially excavated revealing what is likely the eastern wing of a large building occupying the area to its west. This building, like other buildings in the area, consists of several rooms, 38, 30, 23 and 41 that were built around a central courtyard, i.e., Room 201, with inner rooms, 35, 203, at its back. These rooms have a fairly similar plan and most of them are accessed via the central courtyard.

The northernmost spaces are the unexcavated Room 208 and the partially preserved Room 38 (5.2 × 5.1 m in size); south of it is Room 30 (5.1 × 5 m in size), whose northern and southern walls have a pair of ashlar-built engaged pilasters. In addition, an opening (0.9 m wide) that led to the central courtyard was discovered at its southwestern corner, as well as a fragmented lintel decorated with an eight-pointed star or whirling wheel, set within a double medallion at the center (Fig. 2.21) (Chapter 3, No. 6). Two 4th to 6th century CE coins were unearthed in the room (Chapter 9, Cat. Nos. 22, 37). Room 23 has a similar design and dimensions (namely 5.1 × 5 m) and a pair of ashlar-built engaged pilasters in the northern and southern walls (Fig. 2.22). There is an opening (0.9 m wide) leading to the central courtyard in its northwestern corner. In addition, its southern wall has a stepped doorway (1.2 m wide [with narrowing on the outside, 1 m wide] and 1 m thick wall) that led to an inner room (35; 4.9 × 2.4 m in size), probably used for storage. The room revealed a fragmented lintel decorated with a depiction of conch-shaped shell at its center (Fig. 2.23) (Chapter 3, No. 7). Room 41 (5 × 4.9 m in size) has a stepped doorway (0.9 m wide) in its western wall, leading to the room to its west (Room 200). It also has two pairs of ashlar-built engaged pilasters in the western and eastern walls; parts of them were preserved over the height of their cornices (Fig. 2.24). In the northwestern corner, a square-shaped elevated platform (0.7 × 0.5 m and 0.4 m high) was discovered whose function is unclear. The courtyard (201) is located west of the rooms discussed above; as it was only partially exposed, we can only estimate its length (over 15 m). The floor of both rooms (Rooms 41, 200) and courtyard (201, which was at the level of the rooms) was made of packed earth. The partially excavated rooms in the south part of Building I apparently belong to the same building (Rooms 200, 203, 205) (see below).

As stated above, later excavations in the area dug by Cohen (in 1966–1967), carried out by Baumgarten (in 2000), partially revealed the continuation of Area B’s Buildings I and VI. Baumgarten’s excavations were divided into two sub-areas: B1, namely the northwestern continuation of Building I, and B2, which was the northwestern continuation of Building VI. Our plan of Area B (Fig. 2.19) illustrates the remains unearthed in all excavations combined. Unlike Cohen’s excavations, which rarely encountered earlier (pre-Byzantine) remains in Area B, Baumgarten recorded three archaeological strata similar to those documented in Area C (below). Stratigraphically, the earlier remains are attributed to the Early Roman period (likely the 1st and 2nd [and even early 3rd] century CE); only infrequent archaeological remains dated to this period were found in Area B, namely Locus 2013, where a layer of earth that may have been a living surface revealed Nabatean pottery. The second stratum is dated to the Late Roman period (likely the 3rd and 4th century CE), and it is assigned to remains dug into the earlier occupation layer, where the foundations of a building, underneath the southern wing of Building I, were discerned. It seems that some of these building’s remains had been used in the construction of Building I, and some foundations of walls show a different orientation (e.g., W2023, W2032), which apparently relate to this second stratum. This second phase ended, according to Baumgarten, with an earthquake as indicated in units uncovered in Area B by both Cohen and him. Its manifestation is shown by skewed or warped walls, fallen voussoirs and missing worked stones of the inner faces of many of the gravel-made walls of the rooms. Baumgarten assigned this earthquake to the 5th century CE with some hesitation, as coins in the fills of this stratum were tentatively dated to the late 4th century CE, but given their current readings (Chapter 9, Table 9.1, Rooms 41 and 200), some of them can be dated to the 4th–5th centuries CE, making this phase dated to either the Late Roman or Early Byzantine period.

Baumgarten’s excavations in the area managed to complete the uncovering of Room 200 (5 × 4.9 m in size) which had already been encountered in Cohen’s excavations. In the later architectural phase assigned to the Byzantine (5th–6th century CE) period, the eastern wall has a stepped doorway (0.9 m wide) leading from Cohen’s Room 41 (above). Still, the floor level of the room was lower than that of Room 41 by some 0.4 m. Room 200 exhibited two additional openings in the southern and northern walls (0.9 m wide each), which makes this room a vestibule for Building I. It may be added that Room 200 is one of the best-preserved examples of the area’s (and site’s) building method, illustrating how many of the rooms in the compound of Area B may have looked at the time of its occupation (Fig. 2.25). The faces of the outer walls were built of refined ashlars (engaged pilasters and decorative architectural items as well), while the faces of the inner walls were made of partially dressed stones, worked as bossed rectangular-shaped stones that in cases were mortared in elevated courses with the help of smaller fieldstones (Figs. 2.26, 2.27; Sections 10-10, 13-13). In addition, white plaster remains on some walls suggest that the inner walls were plastered. The steps in the doorways are in many cases made with monolithic ashlars. Room 200 also revealed the collapsed voussoirs and stone slabs that formed the room’s ceiling (Fig. 2.26), as well as a fragmented lintel adorned with a Greek cross within a circle (Fig. 2.28) (Chapter 3, No. 9). No less than four 4th and 5th century CE coins were recovered in fills of this room (Chapter 9, Cat. No. 23 and Table 9.1). It is interesting to note that in the fills above the room’s southern opening, and close to surface level, a late (Bedouin?) female burial of the second half of the 19th century (based on a pierced Ottoman coin) was documented (Chapter 9, Table 9.1).

The area south of Room 200 was partially excavated by Cohen (Rooms 203 and 205) and then excavated by Baumgarten (Rooms 2010/2018, 2031). The small room, Chamber 2010/2018 abuts the southern wall of Room 200, making it a later addition that functioned together (Fig. 2.29). Its dimensions are 1.4. × 1.2 m on the inside and 2.2 × 2.2 m on the outside, and it has an opening via a stone threshold on the eastern wall (0.4 m wide) and square-shaped stone basin (0.4 × 0.2 m) in its northeastern corner. Its function is unclear. In fact the chamber is delimited by the western wall of a larger room (2013), 9.5 × 3.5 m in size, whose eastern part was excavated by Cohen (Room 205); hence this chamber appears to be an inner unit on its west side, as occurred in many other rooms at the area and site. The area farther to the east of this room seems to be the building’s open courtyard (Room 203).

- from Chat GPT 4o, 27 June 2025

- from Bernsetin et al. (2025) and Tal et al. (2025)

A particularly diagnostic indicator is the inward collapse of wall segments and roofing materials toward the room interior, implying that seismic shaking caused the failure of structural cohesion. This is further supported by the absence of evidence for fire or human-induced destruction, and by the stratigraphic context of the collapse, which sealed a floor dated to the late Byzantine or early Islamic period (7th century CE). The authors cautiously associate the destruction layer with the 7th-century earthquake(s), possibly the 659 CE Jordan Valley Quake, though they acknowledge the lack of definitive dating evidence to isolate one specific seismic episode.

The site’s limited post-abandonment activity and the well-preserved stratigraphic sequence bolster the interpretation that the collapse represents a primary seismic destruction event. No substantial rebuilding appears to have followed, further implying that the earthquake may have precipitated permanent abandonment of the site.

- from Cohen (1968)

The site occupies approximately 100 dunams and, as E.H. Palmer already pointed out in 1870, the remains of this installation “so scattered and so covered by the earth, that they appear above ground ". In 1953, Prof. Nelson Glueck identified a large Nabataean installation and the objects found on the surface depicted the Greek name of Alexander. While surveying the site in 1965, the Israeli team came to the conclusion that this installation understood a several mounds representing individual buildings which were part of a fort.

The excavations were mainly focused on two of these Hills. On the first northern hill, we uncovered a construction covering more than 800 m2. It consisted of three blocks of dwellings comprising, in total, twelve rooms connected by a courtyard central. The walls were preserved to a height of 1.80 m. The objects found on the floor of the rooms date from the 5th-6th centuries AD. and include Byzantine pots, lamps, jars and coins.

On the central hill, the highest on the site, we have partially cleared four buildings. A street, 2.70 m wide, divides this together in two sectors east and west.

In the western sector, a building, which covers more than 500 m2 consists of eighteen rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The walls were preserved at a height of 2-3 m. A lintel, decorated with rosettes, was among the rubble, near the entrance of one of the rooms. Objects found on the floors of the rooms go back in the 5th-6th centuries AD and include many ceramic objects: lamps, jugs, pots, jugs, jars and small decorated bowls. Two Greek ostraca written in black ink are particularly interesting.

Two similar buildings, covering more than 950 m3, were cleared in the eastern sector. There, too, ceramics and coins indicate the 5th-6th centuries AD. A lintel decorated with a cross is of special interest.

In the southern part of the site, the remains of a Nabataean building were excavated. Ceramic objects collected from the floors of the rooms and court include many beautiful Nabataean sherds decorated and stamped.

Mesad Yeruham appears to have served as a guard post on the ancient Avdat (Oboda) - Mamshit (Kurnub) trade route and its existence is linked to the history of the Nabataeans and the great Roman-Byzantine road in the Negev.

- from Tal et al. (2025:3)

The crystallization of Meẓad Yeroḥam as a continuously occupied site may likely have occurred in the context of the Roman annexation of the Nabatean kingdom and its transformation into the Roman province of Arabia in 106 CE. The annexation was carried out during the reign of Trajan and the death of the last king of the Nabatean kingdom Rabbel II Soter (70–106 CE) may have prompted the official decision of Rome (Bowersock 1983: 70–89). The reason for this annexation may also have been related to the desire of the Roman ruler to limit the potential threat to the borders and improve the empire’s entirety (Erickson-Gini 2010: 47). In addition, benefit from control over the production and trade of aromatics along the Incense Road may have also been a consideration (Isaac 1992: 385).

The previously buffer-zoned Negev, after being fully integrated into the Roman Empire, formed part of the Provincia Arabia (Di Segni 2018). The administrative and military capital was Bostra, re-founded as Nova Traiana (Parker 1986; as also attested on coins RPC III: s.v. Bostra = ΝΕΑϹ ΤΡΑΙΑΝΗϹ ΒOϹΤΡΑϹ [https:// rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/search/browse?q=Bostra]). Major and secondary administrative centers in the Negev were now divided among several urban-oriented settlements. Elusa (Ḥalutza) seems to have been the main administrative capital in the region in both Roman and Byzantine periods, whereas other large settlements, such as Oboda (‘Avdat), located along the Incense Road, and Mampsis (Mamshit), located on a major road leading from the Dead Sea and Transjordan, had a secondary administrative character. Meẓad Yeroḥam, being located between these two settlements, was likely affected by their status during the Roman and Byzantine periods throughout its existence.

The Legio III Cyrenaica controlled the Provincia Arabia between 106 and the mid-3rd century CE. It was based in Bostra but military troops also occupied settlements in the Negev as can be deduced from epigraphic evidence and Roman military tombstones (Mampsis) (Negev 1981). These troops’ activities ensured local security and road maintenance (Erickson-Gini 2010: 50) and, in fact, ensured the continuity of the international incense trade network throughout the Negev. Recently published milestones, including one that gives the distance of 40 miles from Elusa assigned to the days of emperor Publius Helvius Pertinax (193 CE) (Ben David and Isaac 2020: 240–241, IMC 706), as well as others dated to the days of Septimius Severus (200 CE; Ben David and Isaac 2020: 238–240, IMC 705), provide more evidence for this maintenance. A recently published milestone along the Oboda–Meẓad Yeroḥam road indicates the existence of a newly discovered branch of a Roman road between Oboda and Mampsis by way of Meẓad Ḥaluqim–Meẓad Yeroḥam–Meẓad Ḥorvat Bor (Ben David 2019: 139–141, Fig. 7).

The 3rd century CE likely saw an economic crisis that coincided with the disappearance of the Legio III Cyrenaica from the region sometime in the first half of the 3rd century and the probable decrease (or cessation) of the international incense trade network at sites along (and nearby) the Incense Road. This crisis is also confirmed by the absence of coins from the Transjordanian mints dated later than the reign of Elagabalus (218–222 CE), as well as a break in the ceramic tradition, concerning both locally produced and imported vessels (Erickson-Gini 2010: 60–63).

The reforms of Diocletian likely affected Palestine and, more specifically, the Negev as the Persian (Sasanian) threat had to be countered militarily. The so-called Limes Palaestinae was characterized by military strongholds along the Roman road network. In addition, the Legio X Fretensis was transferred from Jerusalem to the harbor economy. Around the same period, the Nabatean inscriptions in the Aramaic alphabet stopped being used in favor of Greek script, with Greek language becoming the province’s official language (for the latest Nabataean inscription in Aramaic script, whose date is 4th–5th century CE, see Erickson-Gini 2010: 189, Fig. 7.5).

The increase in the number of settlements in the Byzantine- period Negev is likely the result of demographic growth after the stabilization of the political (by militarizing the region) and economic situation in the 4th century CE. This imperial effort was likely connected to security maintenance across the long-distance trade routes of the empire connecting regions in Asia and Africa to the Mediterranean. The agrarian nature of many of the (mostly surveyed) Roman-period sites suggest an increase in cultivated agricultural plots by the Early Byzantine period and the cultivation of agricultural species previously unfamiliar in the region (Wacławik 2023: 210–211). It therefore stands to reason that while imperial effort was witnessed in the military sphere, settlements of the Negev were to a large extent based on self-organized economy (Erickson-Gini 2010); individuals within the Negev settlements organized their communal behavior among themselves rather than through external intervention.

The increase in the number of settlement sites of civilian and military character, as well as the tremendous construction of churches (and some monasteries) throughout the Negev (Figueras 2013) relates to demographic growth likely connected to the political stability at a time which allowed the absorption of newcomers to the region. This absorption was not only of active and ex-Roman military personnel, but also civilians, clergy, and monks found the province’s militarized and Christianized character appealing. To this may be added the international movement of pilgrimage, be it to Saint Katherine’s monastery in southern Sinai (Figueras 1995; Whiting 2020) or to a more localized cult such as St. Theodore at Oboda (Erickson-Gini 2022). This brought a plethora of commercial activities to the region, with Meẓad Yeroḥam taking an active role in this movement within the context of its Byzantine occupation, likely providing service to merchant caravans and pilgrims.

The second half of the 6th century CE saw the abandonment of some Negev settlements (as evidenced by coins, i.e. , Mampsis and Meẓad Yeroḥam for the sake of the current introduction). The decline of the flourishing habitation of the Late Byzantine Negev is a much-debated issue and it is addressed in some detail in the context of Meẓad Yeroḥam in the summary of this monograph. Some scholars relate it to the outbreak of the Justinian Plague (541–542 CE) as one of the principal causes of this decline. Earthquakes and droughts were likely an additional reason. Other scholars however, find the treaty of Eternal Peace (between the Byzantines [Justin I] and Sasanians [Khosrow I/Anushirvan], 532 CE) and its aftermath, when the military personnel was no longer financed by the empire, as a more immediate reason for this process. This eventually paved the way for military campaigns of the Sasanian rulers in the early 7th century CE, followed by the Muslim-Arab conquest of the 630s which ended Byzantine rule and opened a new era in the history of the Negev.

- from Tal et al. (2025:6)

the remains of a very large ancient cemetery, whose burial stones have served as a convenient source of material for modern road builders [...] among the remnants of ancient grave markers, we found an intact one with the name “Alexandros” on it written in Greek letters (Glueck 1955: 8) (see Chapter 4).In 1966 the site was surveyed by the southern team of the Archaeological Survey of Israel, led by Cohen (the then Israel Department of Antiquities and Museum Southern District Archaeologist). During this time an ancient cemetery was (re)documented (as had been discovered about a decade earlier by Glueck east of the site), next to the eastern edges of the Yeroḥam—Sede Boqer road (No. 204). It included at least four tombs that were beyond the southeastern edge of the site. The tombs were found some 3 m apart, built of well-dressed soft limestone and covered by large stone slabs and are briefly described in an archival file (Chapter 4).

Excavations at the site began in September 1966 and lasted until April 1967 in the framework of a public park development in the area of the Yeroḥam reservoir (Cohen 1967: 1; Permit No. A-96/1966) (Fig. 1.3). An archival letter from April 1966 suggests that the initiative came from Cohen after inspecting the public park development plans and being aware of the importance of the site’s Roman/Nabatean archaeological remains in its agricultural infrastructure (the existence of terraces and dams). The idea was to have a protected archaeological site within the borders of the public park.

The November-December 1993 season at the site apparently concentrated on Cohen’s excavation Area B’s southwestern part (Permit No. A-2018/1993); unlike the 1966 season and the 2000 season, hardly any archival records were submitted or located (apart from the excavation logbook and plans). There are records of finds recovered from the 1993 season, among them “organic rope, two glass beads, eight coins, two jewels, an ornamented bone comb, an ostracon, a box of metal objects and 37 pottery boxes (Cohen 2021), which we managed to locate in part.

The June 2000 season, directed by Ya‘aqov Baumgarten, lasted intermittently until September of that year in the framework of the Yeroḥam public park development and in order to expedite conservation works (Permit No. A-3241/2000). Excavations were also aimed at answering questions on the nature of the remains of Area B’s northwestern and southwestern parts, where excavations were concentrated, as these parts had only partially been excavated in earlier seasons.

Since the 2000 season the site was left undeveloped. It is an appendage of the public park, but present-day accessibility to the site is easier from the Yeroḥam—Sede Boqer road rather than the public park area. The site itself is rarely visited, being less known than the “Nabataean Towns of the Negev” and less attractive than the isolated road stations and/or fortresses along the Roman road system of the Negev.

As noted earlier, the site has been mentioned in literature since the late 19th century, following excavations and surveys that had been conducted in the region of Meẓad Yeroḥam. The most comprehensive survey was directed by Nahlieli in 1978 in the framework of the Archaeological Survey of Israel (Map 177 – Yeruham). Oddly enough, this survey ignores the map’s principal site, Meẓad Yeroḥam, and documents meager remains dated to the Middle Bronze Age, Early Bronze Age and Iron Age at a number of sites in the surveyed map area, as well as seven Byzantine-period sites whose remains were assigned to farmsteads, dams, agricultural terraces, retaining walls, rock-hewn pits and tombs in the area to the north of the site and the modern town. Two Byzantine sites whose occupation likely continued in the Early Islamic period are documented there as well (Nahlieli and Veinberger 2015).

Relatively small-scale excavations that postdate the publication of the Yeruham survey map (177) may be mentioned here as well. The southeastern periphery (some 1–2 km in distance) was included in a development survey carried out in 2017, where 121 archaeological features were documented and 114 agricultural terrace walls were identified; one of the terrace walls was excavated, another field wall was cleaned, and a nearby field tower was identified. The documented and excavated terraces belonged to an agricultural system that captured the runoff water and the alluvium carried with it, creating conveniently level plots of rich farmland whose proximity to Meẓad Yeroḥam suggests they were part of its agricultural system during the Byzantine period as may also be learned from their construction method (Rasiuk 2019). A trial excavation was conducted in 2019 south of the town of Yeroḥam and northeast of Naḥal Shu‘alim, about 1 km to the southeast of Meẓad Yeroḥam. The excavation unearthed a single oval building, eight agricultural terrace walls and 12 stone heaps (Sapir 2021). Some of these remains may be assigned to Meẓad Yeroḥam’s Byzantine period agricultural hinterland based on similarity in construction methods to other such installations. Another excavation was conducted in 2020 unearthing tumuli built directly on a rocky outcrop each with a built burial cell, but these likely predate the period of Meẓad Yeroḥam’s occupation (Sapir 2023). Two undatable agricultural terraces in the Yeroḥam Park area (Paran 2007) may also be mentioned in this context as they are omitted from the map.

Given the intensive work of the Negev Emergency Survey which was conducted in the contexts of the peace agreement with Egypt that led to the redeployment of the Israel Defense Forces, the Israel Archaeological Survey Society carried out one of its most extensive and important surveys at the time in Israel for about a decade from 1978 to 1988 and for decades thereafter.

Many of the survey maps around that of Yeroḥam are the result of this endeavor, and given the fact that most of them were published during the last decade, our understanding of the settlement dynamics in the area that surrounded the site during the Nabatean/Roman and Byzantine periods is relatively good (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Archaeological Survey of Israel maps around the Map of Yeroḥam (Yeruḥam)

- Masaf Negev – 160

- Yeruham Ridge – 173

- Dimona – 174

- Nahal Revivim – 164

- Yeruham – 177

- Har Zayyad – 178

- Sede Boqer (East) – 168 (Cohen 1981)

- Hamekhtesh Hagadol – 181 (yet unpublished)

- Oron – 182 (yet unpublished)

The survey map to the northwest of Yeroḥam is that of Masaf Negev (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2014), whose surveyed area is divided between the northern Negev Highlands (most of the surveyed region) and the Negev Foothills, without any major site dated to the Classical periods. However, there are no less than five sites of the Nabatean/Early Roman period whose remains include square buildings arranged around a central courtyard (e.g., Site No. 36 [Naḥal Zaḥal 13]; road station?), agricultural terraces and water cisterns; nine sites of the Late Roman period, whose remains include dams and agricultural terraces; and no less than 62 sites of the Byzantine period, whose remains include farmsteads, encampment sites (where there is sherd scatter and buildings or the bases of tents whose walls were built of two rows of fieldstones with gravel filled in between) and water cisterns. It may be added that the Roman period sites continued (in most cases) to be occupied in the Byzantine period; while only three of the Byzantine period sites show occupation in the Early Islamic period.

The survey map to the west of Yeroḥam is that of Naḥal Revivim (Baumgarten and Eldar-Nir 2014), whose surveyed area may represent the boundary between the central and the northern Negev Highlands. There are no major sites dated to the Classical periods, and only one site of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic?) period, whose remains include round and square buildings next to three round courtyards and an animal pen (Site No. 204 [Ramat Boqer 10]; a road station?); 13 sites are attributed to the Roman period, with three to the Early Roman period, four to the Late Roman period and six other sites that could not be ascribed to a specific sub-phase of the Roman period; and no less than 62 sites of the Byzantine period whose remains include farmsteads, animal pens/large courtyards, enclosure walls (of cultivation plots) and agricultural terraces, and water systems (cisterns and dams). It may be added that the Roman period sites continued (in most cases) to be occupied in the Byzantine period; half of the Byzantine period sites were found to be single-period sites; four of the Byzantine period sites show occupation in the Early Islamic period.

The survey map to the southwest of Yeroḥam is that of Sede Boqer (East) (Cohen 1981), whose surveyed area is located in the southern part of the northern Negev Highlands, without any major site dated to the Classical periods. The underrepresented Persian period occupation in the Negev highland is attested at one site (Site No. 65). There are six sites of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period – with three of them preserving architectural remains – Ḥorvat Ḥaẓaẓa (Site No. 83) stands out among them given its impressive Nabatean/ Roman remains and the fact that it may well have been connected to the agricultural hinterland near it with terraces and water cisterns (Site Nos. 99, 101). The three sites of the Roman period are basically adjacent to the Nabatean sites whereas the 45 sites of the Byzantine period are mostly agricultural oriented and divided among isolated buildings, animal pens and water installations – in areas related to the agricultural hinterland of the larger settlements in the area such as Oboda (‘Avdat). Many of the eight sites that show Islamic period occupation have Byzantine period occupation as well and demonstrate the very partial habitation of the Negev Highlands at the time.

The survey map to the north of Yeroḥam is that of Yeroḥam Ridge (Rekhes Yeroḥam) (Eldar-Nir and Traubman 2015), whose surveyed area is bounded on the north by Mount Nokdim, on the east by the Dimona Mountains, on the south and southeast by the Yeroḥam Plain and the site of Meẓad Yeroḥam, on the southwest by the Kaskasim Mountains and on the west by Mount Tzavoa‘, without any major site dated to the Classical periods, and three sites of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period with either later or earlier occupation; six sites of the Roman period; and 53 sites of the Byzantine period. Twenty-three seem to have been founded during this period while for the remainder, their occupation continued or the site was resettled anew after a gap in its occupation. In four of the seven recorded Early Islamic period sites, their occupation continued from the Byzantine period, while the other three were either inhabited anew under Islamic (2) rule or resettled anew after being occupied during the Middle Bronze Age (1).

Additional information comes from more recent work. Northeast of the modern town of Yeroḥam, the Naḥal Avnon area was surveyed in 2011 in the context of railroad construction between Yeroḥam and Dimona. In this survey, some 18 sites with archaeological remains were identified along Naḥal Avnon, mainly farming terraces, structures and walls (Shmueli, Aladjem and Radashkovsky 2012). Additional works in the surveyed area took place in 2020, trial excavations unearthing segments of field walls that were probably related to agricultural systems (Davis 2021; 2024). In 2018 a salvage excavation was conducted at the sites of the Yeroḥam Ridge and Naḥal ‘Eẓem prior to regularizing the status of the Qasr es-Sir Bedouin community. Field (terrace) walls were found whose functions were diverse: delimiting cultivation beds and stabilizing the soil and marking the boundaries of cultivated plots. The wadi-bed terrace walls were built to level the colluvial soil in the wadi channel and to slow and divert the water flow during flooding. The construction methods of the field and terrace walls may well be attributed to the Byzantine period (Mamalya 2021); “a watchman’s hut” without datable artifacts in the area (Paran and Sonntag 2012) may also be assigned to this period.

The survey map to the northeast of Yeroḥam is that of Dimona (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2014), whose surveyed area is divided between two phytogeographic regions in the heart of the central Negev Highlands – the Irano-Turanian region and the Saharo-Arabian region. The map does not include a major site dated to the Classical periods; with only one site of the Nabatean (Late Hellenistic/Early Roman) period; five sites of the Roman period; and forty-six sites of the Byzantine period, of which thirty-four were single period sites. Among the Byzantine period sites are farmsteads, dams, animal pens and other agricultural installations – remains whose character indicates the development of established agricultural activity in the region in the Byzantine period, as seen also in neighboring survey maps. Only two sites on the map show Islamic occupation; one of them also dates to the Byzantine period while the other to the Iron Age.

The survey map to the east of Yeroḥam is that of Har Ẓayyad (Eldar-Nir and Shemesh 2015), whose surveyed area is in the northeastern part of the Negev Highlands, ca. 2 kilometers south of the town of Dimona. The sandy plain of Mishor Rotem and Har Rotem are situated at the map’s northeastern corner. The map includes a major site dated to the Classical periods – that is Mampsis (Mamshit – Kurnub) (Site No. 16), whose occupation lasted from the Nabatean period until the Early Islamic period and whose architectural remains include a town wall and gate, a tower, a manor house and residential buildings, a bathhouse, caravanserai and churches, as well as civilian and military cemeteries. Two additional sites, one single (Nabatean) and the other (Nabatean/Roman) brings the total number of Nabatean/Roman period sites on the survey map area to three; as in other survey maps of the Negev Highlands, the number of Byzantine period sites is the highest; 19 sites are recorded on the current one. Their architectural remains include buildings, courtyards, animal pens and a few water installations (a dam and two cisterns), as the agricultural potential of the Mampsis periphery was limited and the economy relied more on trade caravans. Early Islamic occupation in the map area is only attested in Mampsis.

The survey maps to the south (Hamekhtesh Hagadol) and southeast (Oron) of Yeroḥam are yet unpublished in detail; they are briefly mentioned in part in a manner that suggests a somewhat similar picture to their surrounding maps (Eldar 1982).

In sum, the survey map of Yeroḥam and those that surround it suggest somewhat similar settlement dynamics from the second half of the first millennium BCE to the first millennium CE. The near break of habitation after the Iron Age, in which hardly any settlement of the area during the Persian and Early Hellenistic periods is recorded, agrees with the few settlements known from this period in the entire region of the Negev. As stated above, the Late Hellenistic (or early Nabatean) settlements recorded are difficult to assess based on the surveys carried out and the published material, as the painted Nabatean pottery that assisted the surveyors to identify Nabatean settlements is normally dated to the Roman period. Early Nabatean settlements in the area discussed above seem to be numbered and it is clear that the later Nabatean settlements of Early Roman date were much more prevalent. As the Negev’s Imperial Roman occupation began in the early 2nd century CE, more settlements were established but the total number of all these Hellenistic and Roman settlements seems to be marginal when compared to the numerous Byzantine period sites of the Negev whose raison d’être is related to the Christianization of Palaestina Tertia. The sharp decrease in the number of Early Islamic sites should be understood against the lack of imperial interest of the ruling Islamic authorities.

- from Tal et al. (2025:23)

Building I is located in the western part of the area, possibly revealing the eastern wing of a more extensive building (Figs. 2.18 and 2.19). It is flanked by Building II on its east. Its excavation area was enlarged in the 2000 season of excavations. East of Building II there is an alley (44) separating Building II from Building III; the length of the alley is some 18.5 m. Building III is located to the east of this alley; Building IV is the easternmost building excavated in the area and, like other buildings, it consists of a central courtyard that has four different wings around it. Building V is rather similar to Building II in that the excavations uncovered only part of a wider building. The southernmost building in the area is Building VI, which also consists of a central courtyard around which various wings were built. The excavation of Building VI was also enlarged in the 2000 season.

This building is the westernmost building excavated in the area, adjacent to Building II on its east. It was only partially excavated revealing what is likely the eastern wing of a large building occupying the area to its west. This building, like other buildings in the area, consists of several rooms, 38, 30, 23 and 41 that were built around a central courtyard, i.e., Room 201, with inner rooms, 35, 203, at its back. These rooms have a fairly similar plan and most of them are accessed via the central courtyard.

The northernmost spaces are the unexcavated Room 208 and the partially preserved Room 38 (5.2 × 5.1 m in size); south of it is Room 30 (5.1 × 5 m in size), whose northern and southern walls have a pair of ashlar-built engaged pilasters. In addition, an opening (0.9 m wide) that led to the central courtyard was discovered at its southwestern corner, as well as a fragmented lintel decorated with an eight-pointed star or whirling wheel, set within a double medallion at the center (Fig. 2.21) (Chapter 3, No. 6). Two 4th to 6th century CE coins were unearthed in the room (Chapter 9, Cat. Nos. 22, 37). Room 23 has a similar design and dimensions (namely 5.1 × 5 m) and a pair of ashlar-built engaged pilasters in the northern and southern walls (Fig. 2.22). There is an opening (0.9 m wide) leading to the central courtyard in its northwestern corner. In addition, its southern wall has a stepped doorway (1.2 m wide [with narrowing on the outside, 1 m wide] and 1 m thick wall) that led to an inner room (35; 4.9 × 2.4 m in size), probably used for storage. The room revealed a fragmented lintel decorated with a depiction of conch-shaped shell at its center (Fig. 2.23) (Chapter 3, No. 7). Room 41 (5 × 4.9 m in size) has a stepped doorway (0.9 m wide) in its western wall, leading to the room to its west (Room 200). It also has two pairs of ashlar-built engaged pilasters in the western and eastern walls; parts of them were preserved over the height of their cornices (Fig. 2.24). In the northwestern corner, a square-shaped elevated platform (0.7 × 0.5 m and 0.4 m high) was discovered whose function is unclear. The courtyard (201) is located west of the rooms discussed above; as it was only partially exposed, we can only estimate its length (over 15 m). The floor of both rooms (Rooms 41, 200) and courtyard (201, which was at the level of the rooms) was made of packed earth. The partially excavated rooms in the south part of Building I apparently belong to the same building (Rooms 200, 203, 205) (see below).

As stated above, later excavations in the area dug by Cohen (in 1966–1967), carried out by Baumgarten (in 2000), partially revealed the continuation of Area B’s Buildings I and VI. Baumgarten’s excavations were divided into two sub-areas: B1, namely the northwestern continuation of Building I, and B2, which was the northwestern continuation of Building VI. Our plan of Area B (Fig. 2.19) illustrates the remains unearthed in all excavations combined. Unlike Cohen’s excavations, which rarely encountered earlier (pre-Byzantine) remains in Area B, Baumgarten recorded three archaeological strata similar to those documented in Area C (below). Stratigraphically, the earlier remains are attributed to the Early Roman period (likely the 1st and 2nd [and even early 3rd] century CE); only infrequent archaeological remains dated to this period were found in Area B, namely Locus 2013, where a layer of earth that may have been a living surface revealed Nabatean pottery. The second stratum is dated to the Late Roman period (likely the 3rd and 4th century CE), and it is assigned to remains dug into the earlier occupation layer, where the foundations of a building, underneath the southern wing of Building I, were discerned. It seems that some of these building’s remains had been used in the construction of Building I, and some foundations of walls show a different orientation (e.g., W2023, W2032), which apparently relate to this second stratum. This second phase ended, according to Baumgarten, with an earthquake as indicated in units uncovered in Area B by both Cohen and him. Its manifestation is shown by skewed or warped walls, fallen voussoirs and missing worked stones of the inner faces of many of the gravel-made walls of the rooms. Baumgarten assigned this earthquake to the 5th century CE with some hesitation, as coins in the fills of this stratum were tentatively dated to the late 4th century CE, but given their current readings (Chapter 9, Table 9.1, Rooms 41 and 200), some of them can be dated to the 4th–5th centuries CE, making this phase dated to either the Late Roman or Early Byzantine period.