Magdala

Fig. 7

Fig. 7Aerial view of Magdala–Taricheae from West. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (M. Eisenberg 2010)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Migdal | Hebrew | מגדל |

| al-Majdal | Arabic | المجدل |

| Magdala Nunayya | Aramaic in the Babylonian Talmud | מגדלא נוניה |

| Magdala Sebaya | Jewish sources | |

| Dalmanoutha | possibly in Mark 8:10 | |

| Magadan | possibly in Matthew 15:39 | |

| Taricheae | Greek | Ταριχαία or Ταριχέα |

| Magdala | Aramaic | מגדלא |

Magdala was an ancient city on the shore of the Sea of Galilee - located ~ 3 km. north of Tiberias. Because it is referred to as Magdala Nunayya - "Tower of Fishes" - in the Babylonian Talmud, it may also be the location of Taricheae - "the place of processing fish" in Greek. The Migdal synagogue, the oldest synagogue found thus far in the Galilee, was discovered here and Jesus' disciple and possible companion Mary of Magdala (popularly known as Mary Magdalene) is reputed to have been born here. The harbor of Magdala was uncovered during the 2007–2011 Magdala Project archaeological campaigns and appears to exhibit three phases of use: late Hellenistic (2nd–1st centuries B.C.), Early-Middle Roman (1st–3rd century A.D.) and Byzantine (6th–7th centuries A.D.) (deLuca and Lena, 2014).

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Schematic Map of the Sea of Galilee: Anchorages and Coastal Sites. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 2 - Topographic Map

of the area from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Topographic Map of the Area of Magdala–Taricheae and surroundings. The letters show the digs. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Schematic Map of the Sea of Galilee: Anchorages and Coastal Sites. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 2 - Topographic Map

of the area from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Topographic Map of the Area of Magdala–Taricheae and surroundings. The letters show the digs. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Annotated Satellite View

of Magdala from biblewalks.com

- Magdala in Google Earth

- Magdala on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 3 - General Plan

of the Magdala Project from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General Plan of the Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 3 - General Plan

of the Magdala Project from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General Plan of the Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 4 - Harbors plan

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 5 - Byzantine Harbor

plan from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 4 - Harbors plan

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 5 - Byzantine Harbor

plan from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 5 - Plan and sections

of Areas E and F from Lena (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Areas E and F, eastern side, plans and views

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Lena (2013)

- Fig. 5 - Plan and sections

of Areas E and F from Lena (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Areas E and F, eastern side, plans and views

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Lena (2013)

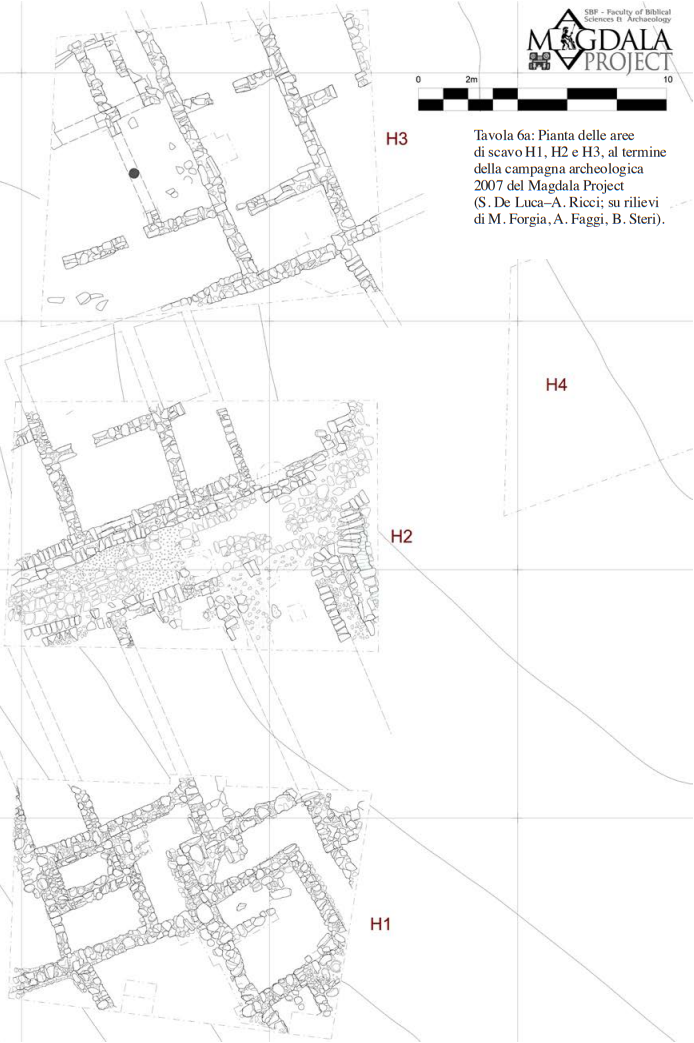

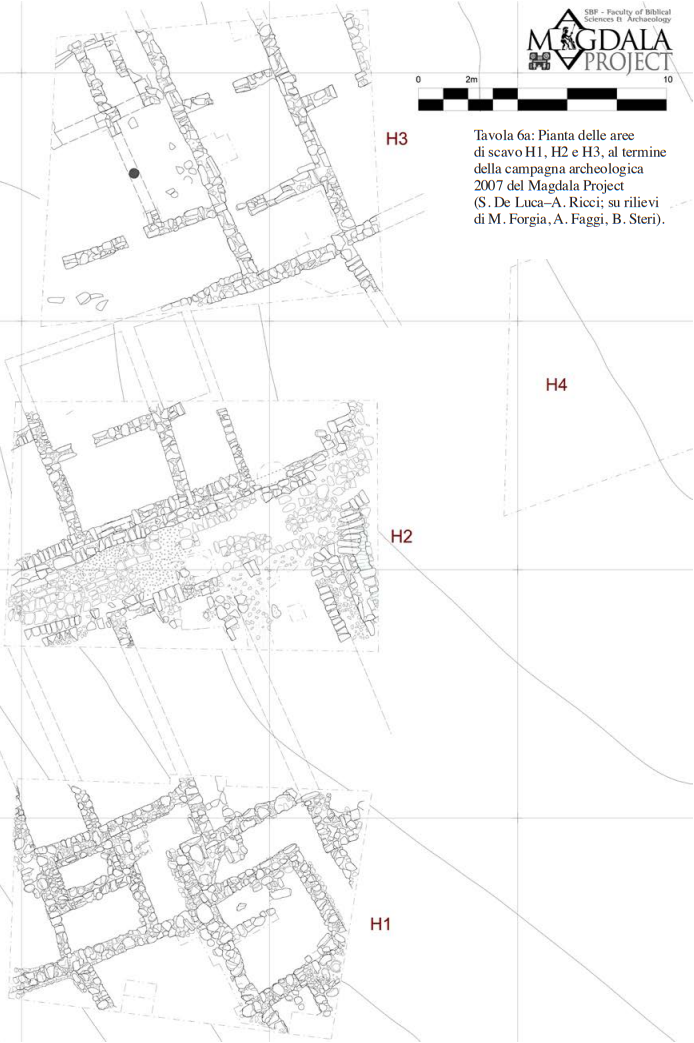

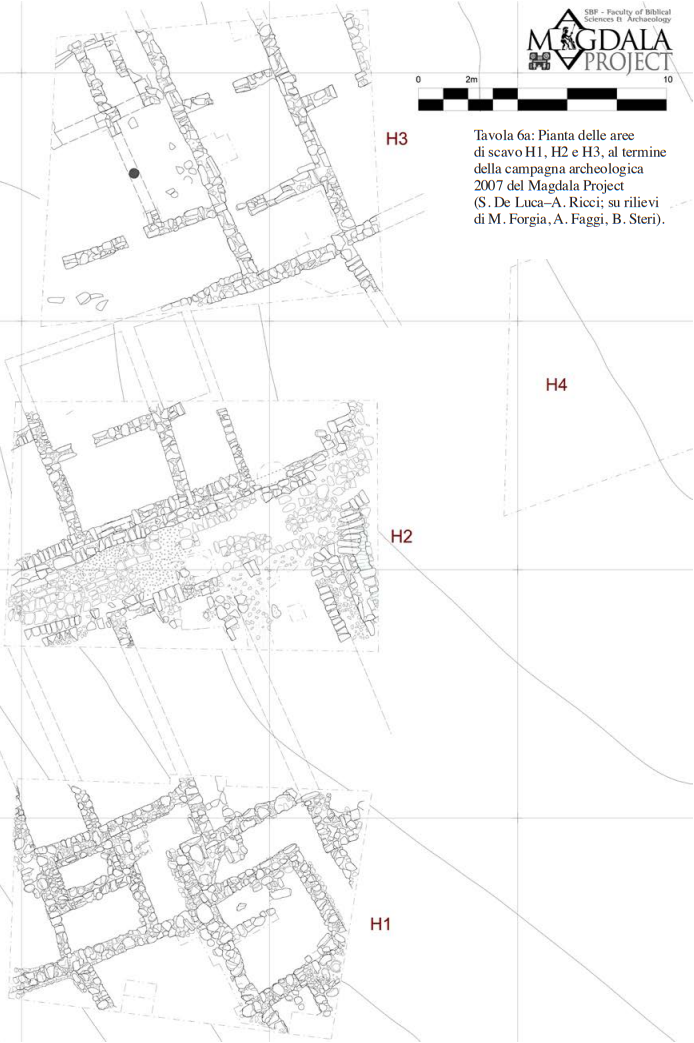

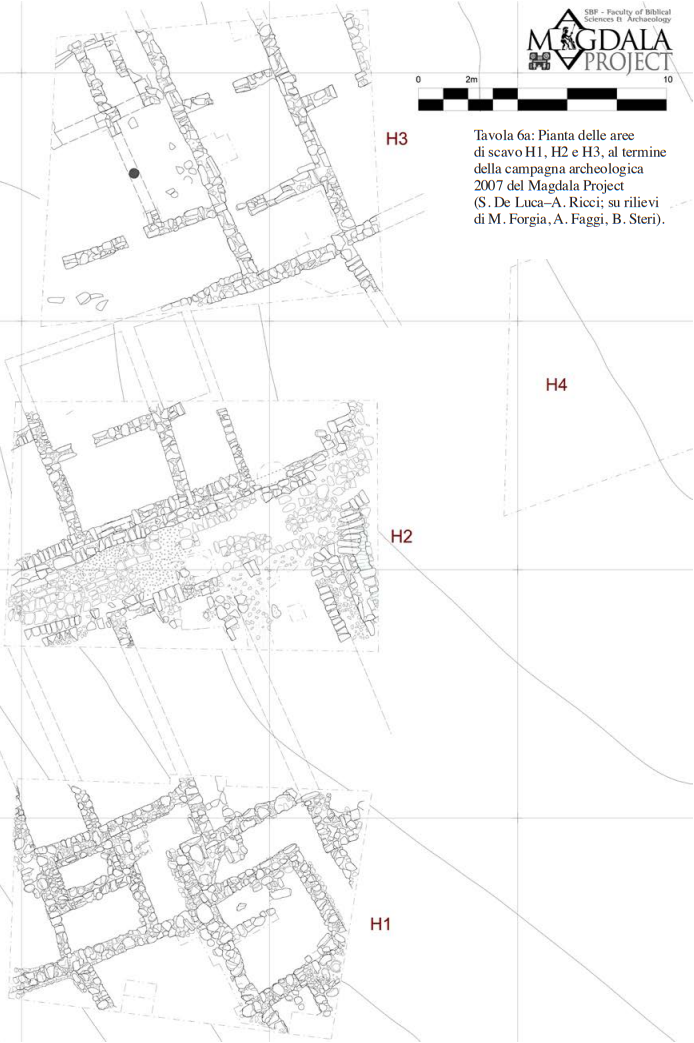

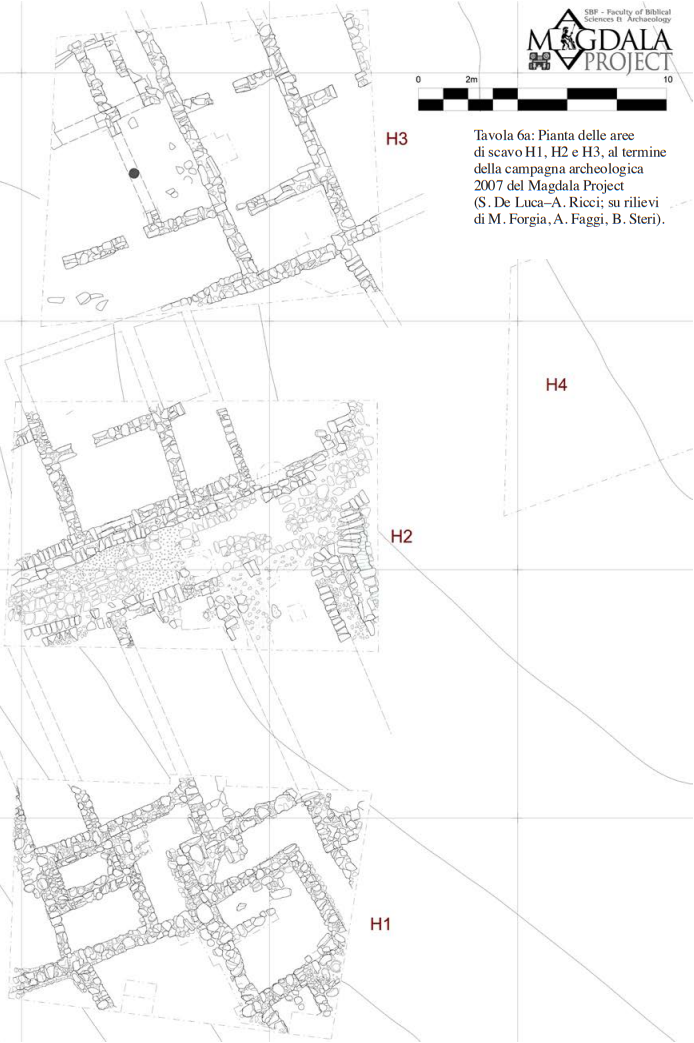

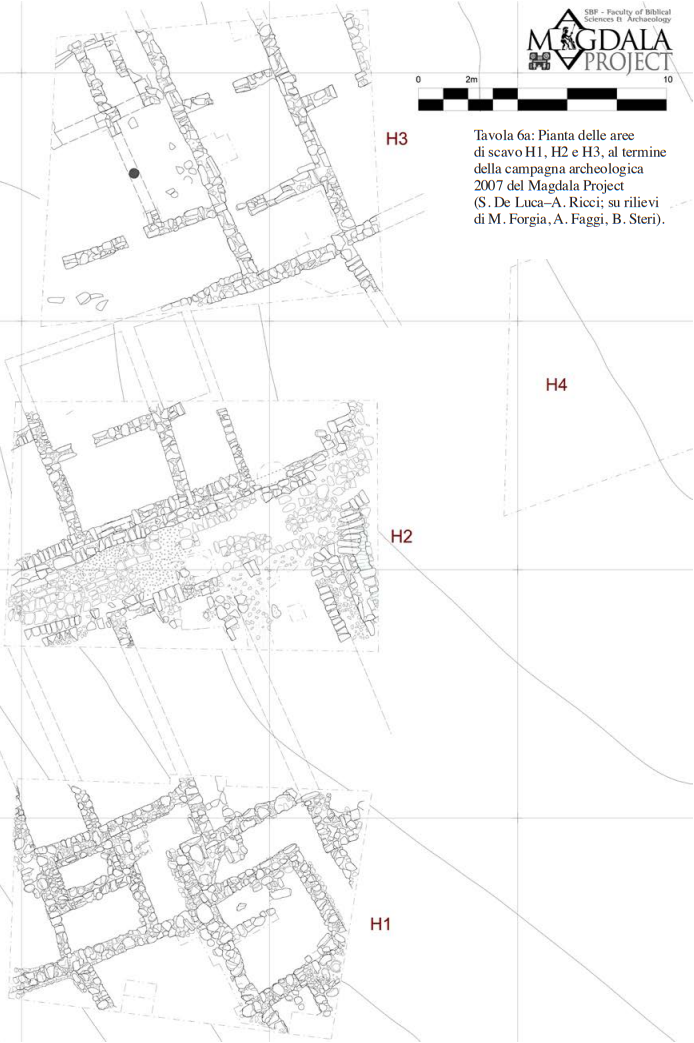

- Plate 6 - Plan of Areas

H1, H2, and H3, at the end of the 2007 season from De Luca (2009)

Plate 6

Plate 6

Plan of excavation areas H1, H2, and H3, at the end of the 2007 season of the Magdala Project

(S. De Luca—A. Ricci; relief from M. Forgia, A. Faggi, and B. Stern).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 7 - Collapses in

Area H1 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 7

Plate 7

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H1. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—M. Forgia).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 8 - Collapses in

Area H2 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 8

Plate 8

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H2. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—A. Faggi).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 9 - Collapses in

Area H3 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 9

Plate 9

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H3. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—B. Stern).

De Luca (2009

- Plate 6 - Plan of Areas

H1, H2, and H3, at the end of the 2007 season from De Luca (2009)

Plate 6

Plate 6

Plan of excavation areas H1, H2, and H3, at the end of the 2007 season of the Magdala Project

(S. De Luca—A. Ricci; relief from M. Forgia, A. Faggi, and B. Stern).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 7 - Collapses in

Area H1 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 7

Plate 7

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H1. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—M. Forgia).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 8 - Collapses in

Area H2 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 8

Plate 8

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H2. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—A. Faggi).

De Luca (2009 - Plate 9 - Collapses in

Area H3 from De Luca (2009)

Plate 9

Plate 9

Magdala/Taricheae, Area H3. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM

(S. De Luca—B. Stern).

De Luca (2009

- Fig. 10 - Sections from

de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008)

JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 10 - Sections from

de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008)

JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 20 - Harbor evolution

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20

Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 20 - Harbor evolution

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20

Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 5 - Aerial photo

of Areas Hl-H2-H3 at the end of the 2007 season from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Aerial photo of Areas Hl-H2-H3 at the end of the 2007 archaeological campaign of the Magdala Project

(Skyview © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 8 - Aerial photo

of Area H1 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

General photo of Area H1 at the end of the excavation. Towards the West

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 9 - Aerial photo

of Area H1 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Aerial photo of Area H1 at the end of the 2007 campaign

(Skyview © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Figs. 25 & 26 - Aerial photos

of Area H2 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 25 (top)

Fig. 25 (top)

General photo of Area H2 at the end of the excavation. Towards the East

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

Fig. 26 (bottom)

Aerial photo of Area H2 at the end of the excavation.

(Skyview, © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 28 - Possible roof

beam collapse in Area H2 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Excavation documentation of Area H2 South East sector. Detail of the covered conduit USM 60-61-116 under the paved road USM 5. Towards the North

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 30 - Possible roof

beam collapse in foreground (Area H2) from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 30

Fig. 30

Excavation documentation of Area H2 South East sector. On the left: behind the covered conduit USM 60-61-116, you can see the US 59 alignment, the US 52 floor preparation, covered by the US 34 layer. On the right : remains of the paving of the USM 5 street. Towards the West

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 35 - Collapse in

Area H2 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 35

Fig. 35

Excavation documentation of Area H2 North West sector. Detail of the particular elements of the US 13 collapse, in the US 24 destruction layer, against the USM 17 façade wall. Southward

(Skyview © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 37 - Aerial photo

of Area H3 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 37

Fig. 37

General photo of Area H3 at the end of the excavation. Towards the South

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 38 - Aerial photo

of Area H3 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 38

Fig. 38

General photo of Area H3 at the end of the excavation. Towards the East

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 39 - Aerial photo

of Area H3 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

Aerial photo of Area H3 at the end of the excavation.

(Skyview © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 42 - Ordered collapse

in H3 from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 42

Fig. 42

Excavation documentation of Area H3 Northern sector. Detail of the collapsing structures USM 50, near USM 47 on the left, and USM 48 behind. Towards the South.

(D. Zanetti © Magdala Project)

De Luca (2009) - Fig. 80 - Ordered collapse (?)

from De Luca (2009)

Fig. 80

Fig. 80

Caption missing from report - JW: possibly Area M

De Luca (2009)

- Aerial View of Areas

C, D, E, and F from biblewalks.com

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

click on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab

Used with permission from from biblewalks.com - Fig. 15 - Excavated Roman port

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

General view of the Roman Port of Magdala, from South-East. Courtesy of S. de Luca © Magdala Project (V. Sedia 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- from De Luca (2009)

| Period | Dates |

|---|---|

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BC |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-63 BC |

| Early Roman | 63 BC-70 AD |

| Middle Roman | 70-270 AD |

| Late Roman | 270-350 AD |

| Early Byzantine | 350-450 AD |

| Middle Byzantine | 450-550 AD |

| Late Byzantine | 550-650 AD |

| Early Arab I | 650-800 AD |

| Early Arab II | 800-1000 AD |

| Middle Arab I | 1000-1200 AD |

| Middle Arab II | 1200-1400 AD |

- from Lena (2013)

The pottery classification of the site follows the typology set out by S. Loffreda (2008a–c)

- Lena (2013)

| Stratum | Period | Dates | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Late Roman to the Islamic | a level of abandonment, consisting of an accumulation of very fine and dusty clayey soil with few ceramic inclusions, dating from the Late Roman to the Islamic periods. | |

| II | Late Roman | A hard packed conglomerate layer of non-worked stones, including cobblestones,

pebbles, limestone and basalt flakes, bonded with light mortar, was discovered

only in the entrance hall. This layer, which was bound by a barrier of blocks

and stones before the arch, closed up the earlier entrance from south and

raised the pavement of the entrance hall up to the level of the most recent entrance The findings give a terminus post quem of the Late Roman period. A layer of waste, containing fragments of ochre, reddish, pearl-white, and turquoise green painted plaster that was probably used for decoration with stripes and floral patterns, was identified in the basin. In addition, a few pieces of egg-and-dart stucco were collected. The same context yielded a group of rare wooden findings, exceptionally preserved in the water-saturated mud, including pieces of bars, planks and muntins with nails, joints and wedges. These wooden pieces, which may have been parts of a trellis for false ceilings, were placed in overlapping horizontal strips that apparently crossed and ended a little below in long and very thin panels. A mat of intertwined canes and vegetable materials, such as vine-leaves, thin canes, olive branches and palm, bound by lime mortar has been found in several places between woods and frame. The mortar contained lake sand, small shells, fruit stones and vegetable frustules. |

|

| I | end of the Hellenistic to the end of the Early Roman (1st Jewish War) | The collapse of the wooden structure covered a layer of abandonment (thickness 0.5–0.6 m) where several findings

were found, including glass aryballoi, soft limestone vessels, a fish-hook, cramp-irons, blades, nails, faunal remains

and a remarkable assemblage of pottery dating from the end of the Hellenistic to the end of the Early Roman periods.

Among the forms to be noted are Kefar Hananya type globular cooking pots, Pent10 (Loffreda 2008a:184–185), Pent11

(Loffreda 2008a:185–186), and Pent12 (Loffreda 2008a:186–187), cooking bowls, Teg12 (Loffreda 2008a:204–205), and

Teg14 (Loffreda 2008a:206–207), two intact unguentaria, amphorae, Anf12 (Loffreda 2008a:125–126), and Anf13

(Loffreda 2008a:126–127), stone vessels, and Herodian oil lamps (Loffreda 2008a:42–45). Moreover, the mud

fill contained an extraordinary group of wooden vessels, including a plate, a small cup and two rounded cups,

which have been transferred, together with the comb from E11, to Pisa to be consolidated and restored at the

Centro di Restauro del Legno Bagnato del Cantiere delle Navi Antiche. Therefore, the homogeneous pottery assemblage from this stratum testifies to a phase of use preceding the sudden destruction that occurred before the end of the first century CE and is ascribed to the violent conquest of Magdala by Titus and Vespasianus. |

- from Lena (2013)

The pottery classification of the site follows the typology set out by S. Loffreda (2008a–c)

- Lena (2013)

| Stratum | Period | Dates | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Whitish beaten earth and rubble (L325), leveled over the upper horizon where, amongst the finds, a Constantius II coin (350–361 CE) was found | ||

| II | A collapse layer (L329) below Layer I is composed of worked stones mostly dressed, rubble and several fragments of colored plaster, especially in proximity to the wall. The coins retrieved from the collapse dated from Alexander Jannaeus to Herod the Great | ||

| III | A layer of lime sand with pebbles and shell remains, which is characterized by the absence of any ceramic or other anthropogenic remains. The sediments’ surfaces follow the west–east direction in the south and north sections, and south–north direction in the east section | ||

| IV | A cobble pavement (L331) of various sized natural pebbles placed in correspondence with W317. Potsherds from the Hellenistic–Early Roman periods were discovered in the ballast, as well as two coins from the first century CE. The ballast’s surface, slanting from west to east, was partially affected by the collapse of roughly-hewn lime blocks before being buried | ||

| V | A dark clayey layer, containing pre-Roman material (L401), before both L331 and apparently W317 were placed. |

- Fig. 3 - General Plan

of the Magdala Project from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General Plan of the Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 3 - General Plan

of the Magdala Project from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General Plan of the Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 4 - Harbors plan

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 5 - Byzantine Harbor

plan from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 4 - Harbors plan

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014) - Fig. 5 - Byzantine Harbor

plan from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 5 - Plan and sections

of Areas E and F from Lena (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Areas E and F, eastern side, plans and views

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Lena (2013)

- Fig. 5 - Plan and sections

of Areas E and F from Lena (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Areas E and F, eastern side, plans and views

Color Code

- green - Hasmonean and Herodian (2nd century BC-1st AD)

- yellow - early and middle Roman (1st - 3rd century AD)

- blue - late Roman and Byzantine (3rd-7th century AD)

- purple - Arab and medieval (7th-11th century AD)

- gray - encumbrances of the paved road axes

Lena (2013)

- Fig. 10 - Sections from

de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008)

JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 10 - Sections from

de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008)

JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 20 - Harbor evolution

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20

Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Fig. 20 - Harbor evolution

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20

Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

- Aerial View of Areas

C, D, E, and F from biblewalks.com

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

click on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab

Used with permission from from biblewalks.com - Fig. 15 - Excavated Roman port

from de Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

General view of the Roman Port of Magdala, from South-East. Courtesy of S. de Luca © Magdala Project (V. Sedia 2011)

De Luca and Lena (2014)

de Luca and Lena (2014:139) dated a collapse layer in Area F to the 363 CE earthquake.

For causes yet unknown, the harbor basin was silted by 45–60 cm lacustrine sandy deposits covered by conglomerates of gravel (Units 3–4) typical of beaches areas, rich in mollusc shells and byoclasts (in particular melanopsis are copious). The imbrication of clasts, principally oriented eastwards and only partially toward the west, reveals the strongest water motion, typical of upper beach/foreshore environment. The potsherds from the conglomerates date back to the Middle-Late Roman (3rd century A.D.) period and give a terminus post quem for its formation (cf. Figs. 10 and 20 - see above). On this layer of pebbles, probably due to the earthquake of 363 A.D., there was the collapse of the elevation of the eastern portico to which several architectural elements – voussoirs, worked wall stones, corbels – belong. A great quantity of fragments of wall plasters with traces of paintings in vermilion red hues, burned ochre, yellow ochre, copper green, black and Egyptian blue, have been uncovered in context with pieces of ochre, red and caeruleum pigments, as well as coins and potsherds from the 3rd–4th century A.D.

Close to the southern area, the [earlier] collapse was leveled and covered with crushed and pressed limestone of an Early Byzantine-Islamic building that was probably the service quarter of the monastery. The Byzantine structures were completely destroyed, greatly looted and consequently covered by a layer of pebbles, deposited by the lake which had dramatically risen toward the middle of the 8th century A.D., almost certainly due to the effect of the earthquake of 749 A.D. (cf. Fig. 15).

De Luca (2009:352) hypothesized that the collapse and relative abandonment of the buildings in sector

H

was a consequence of the earthquake that affected the region in 363 AD

while noting that the most precise chronological indicators seem to stop around a forty years

earlier

. De Luca (2009:352) reports that from the entire excavation of areas H1, H2 and H3

no finds from the Byzantine period

were found - not even a single sherd

.

... With the new excavation, an area of approximately 500 m2 was investigated (cf. Table 6), divided into three quadrangular trenches named from South to North:

- H1 (14 x 10 m)

- H2 (15 x 10 m)

- H3 (14 x 11 m)

The thin superficial layer (US 0; US 4; US 7; US 317), starting from an average starting altitude of -205.60 m, has a thickness varying from 30 to 50 cm., has a horizontal and flat trend, slightly inclined from West to East, and is referable to a recent phase of agricultural exploitation of the land. It covered a fairly evident level of collapse, and was generally better preserved in H3. For the remaining areas, however, a phenomenon of removal of the archaeological layers seems to have occurred. The event must have occurred after 1940 (Bagatti 2001, 78-71, fig. 34), a terminus indicated by the Palestinian coin (CF 159) found at US 117 and by the British coin (CF 94) at US 4, and it seems historically connected with the military operations following 22 April 1948, with the evacuation of approximately 400 inhabitants of the village of el-Mejdel and the demolition of their homes (see al-Majdal at PalestineRemembered.com).

Since these were violent and sudden outcomes, apparently a single causative event, it seemed useful to leave the surviving collapses in situ until the documentation and study phases were completed, possibly also from a geological point of view. The interpretation, which will have to find further confirmation, leads to the hypothesis of the collapse and relative abandonment of the buildings in sector H as a consequence of the earthquake that affected the region in 363 AD, although the most precise chronological indicators seem, to date, to stop around a forty years earlier. It is a significant fact that from the entire excavation of areas H1, H2 and H3 no finds from the Byzantine period came from, not even a single sherd.

- from De Luca (2009:352)

An in-depth study was carried out inside collapse US 91-94, delimited by the square (5 x 5 m) formed by USM 16, USM 17 (at an altitude of -205.70 m), USM 57 (at altitude of -205.85 m) and USM 93, south-east of the trench. This environment, with walls 35 to 40 cm thick, as a whole is to be considered prior to the Middle Roman period, when it was completely hidden by the compacted gypsum and lime pavement US 86 (at an altitude of - 206 m, 04), rich in faunal remains (see Figure 10). The numerous ceramic fragments contained in US 86 - of which a witness was left near the south-east corner of the box (see Figure 12) - are easily datable and include an assortment of common tableware ceramics, of the usual Kefar Hanania typologies of the 1st, 2nd and early 3rd centuries. AD, associated with rarer materials such as lamps of the Luc1.2 type (50 BC-50 AD) and Luc3 type (middle Roman period), amphorae of the Anf10, Anfll types and four coins, among which one is by Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) and another Roman provincial from the 2nd - mid 3rd century AD. US 86, on which, at USM 95, two bottoms of large, thick-walled preserving jars were also found, affected the entire eastern sector of the trench, starting from USM 45 and USM 16.

The survey exposed USM 93 (at an altitude of -206.06 m) for approximately 1 meter of depth, highlighting a regular infill, perhaps the closure of a door originally communicating with another room to the south. Here, in fact, it was identified a probable beaten floor level, US 96, on which an intact pot (Pt 6570) with a globular body and everted and convex lip, of the Pent5 type, was found and, incorporated inside USM 97, a bell-shaped amphora (Pt 7808-7810) quite complete up to the curvature of the bottom, with amygdaloid section rim and double handles under the shoulders, of the Anf3 type, both typical of the late Hellenistic period, as also indicated by the three coins (CF 179; 204; 205 ) by Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) found there at the same time (cf. Figure 12). In addition to a well-polished basaltic ring weight (see Figure 13) for fishing nets and two other specimens of Luc1.2 similar to Pt 6236 from US 86, among the materials collected from the US 91-94 collapse, it is note, a hoard of 54 prutoth, mainly from the Hasmoneans and concentrated in a small space near the northern face of the infill of USM 93. Of these, 1 belongs to Demetrius III (96-87 BC) of the Seleucia Pieria mint; 2 are generally attributable to the Hasmonean era (103-40 BC); 1 is from the Sidon mint (100-98 BC); 1 is attributable to a Tyrian mint of Ascalon (98/97-84/85 BC or 68/67 BC); 23 are clearly minted in Geru Salemme by Alexander Jannaeus; 11 are from Herod the Great, also from the Jerusalem mint; and finally 1 is of the procurators Marcus Coponius or Ambibulus (6-9 AD or 9-12 AD). The consistency of the deposit, which supports the dating of the cebranches associated with it, among which several fragments of thick-walled amphorae of the Anf2 and Anf3 types can be seen, encourages us to place the time of the US 91-94 collapse, the cause of which cannot be established at the moment, as after the first decade of the 1st century AD, correcting here what was previously supposed. The stone elements that compose it are predominantly parallelepiped in shape, carefully or roughly squared and could therefore reasonably come from the walls that contain it. In particular, given the position of the hill inclined from South-West to North-East, it should refer to USM 93 and USM 16.

- from De Luca (2009:355)

- from De Luca (2009:355)

- from De Luca (2009:356)

- from De Luca (2009:356)

The loose, inconsistent accumulation of natural rounded boulders, which constitutes US 90 (from which a coin of Alexander Severus minted in Caesarea. Maritime 222-235 AD comes from), covers the beaten US 106, a very tenacious whitish layer with several inclusions such as breccia, shards, flakes and waste of soft chalky stone. In turn, the floor of crushed earth US 106 covers the collapse of US 107. We do not have a clear picture of the previous structures, but only some chronological elements which come from:

- late Hellenistic ceramic finds, associated with a coin of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) from US 111, deepened by cm. 80/90

- from the anti-Roman finds on the limestone bed US 102 (under the collapse US 103 and US 105), which also include fragments of Herodian lamps, a portion of large chalky stone hydriae carved on a wheel, a group of large nails and metal studs with a square section (Mtl 82-90) belonging to a door (Durante 2001, 72-72, fig. 18) and a bronze speculum with molded decoration (Pec 17).

- from De Luca (2009:357)

USM 15 extends for over 6 m (at an average altitude of -205.15 m) from South-West to North-East in the North-West quadrant of the trench (see Figures 20- 21). The masonry structure is composed of roughly squared ashlars, sometimes flattened on the exposed face, placed in fairly horizontal and parallel rows, also thanks to horizontal interventions. The lithic elements, mainly basaltic, of medium-large size, are assembled with a core of light mortars and small stones. Its axis rotates a few degrees coinciding with the edge junction with USM 40 (2.2 x 0.5 m, at an altitude of -205.20 m) towards the North. In fact, along the southern face of the western section of USM 15, a tooth protruding from it cm. 30, probably referable to its first phase.

USM 63 joins the western head of USM 15 (2.6 x 0.9 m, at an altitude of -205.02 m). The space between this and USM 40 is affected by the US 100 collapse (2.3 x 2.6 m) with characteristics similar to those of the aforementioned US 109 collapse. It is composed of mostly parallelepiped-shaped ashlars, which fell head-on with a SouthEast trend / North-West, which we were able to follow up to 60/70 cm. below the USM 15 accent, without, at the moment, having been able to find its laying surface. In it there was a cylindrical fragment with a hollow on the base, perhaps a limestone roller (St 53), of the kind used to press attics and floors. Even the large room 3.6 m east of USM 40 is affected by a collapse, US 101, formed by the collapse of wall ashlars; however, the quality of the lithic elements found here seems lower than that of US 100 and US 109. In plan view, the eastern wall of the room appears to be aligned with USM 55, which allows us to imagine the entrance to the building from the USM road 5 in H2.

At the top of the center of the south face of USM 15, a deep sondage was dug to verify the stratigraphy (see Figure 22). The survey (1.3 x 1.5 x 1.5 m) made it possible to document the following:

- the presence of an artificial fill, US 39, meeting the characteristics of a drain at least 80 cm high. It consists of a white layer with a large quantity of inclusions: faunal waste (animal bones and teeth, mollusc valves), charcoal, glass — including the ribbed cup Gl 444-445, corresponding to type 3 of the Isings classification (Isings 1957) -, ceramic fragments from the ancient Roman period (Herodian lamps Luc2.1 and 2.2, Pent10 pots), middle and late (mainly globular pots with grooved lips of the Pent12.1 and Pent12.2 type like the Pt specimen 7927 reassembled almost entirely). Four coins were also found in the dump: one of Herod the Great (40/37-4 BC), one of the procurators Coponius or Ambibulus (6-9 or 9-12 AD), a Roman provincial coin from the 2nd - 3rd century AD, and one of the Ptolemies (1st century BC?)

- the primitive construction phase of USM 15, jutting out from the upper 10 to 15 cm. with a small axial rotation

- the existence of a wall of the first phase, USM 44 (at an altitude of -206.35 m), which connects to the previous one and bends 90 degrees towards the south, under USM 2

- a floor level - US 98 - in rammed earth (often 20/25 cm) containing late Hellenistic materials, on which a globular pot (Pt 8230) from the Kefar Hanania factory of the Pent10 type (CPRG form 4A) was placed, form which dates back to between the century BC and the century AD, containing a Hasmonean coin (CF195). Three other coins, one corroded and two assigned to Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC), were collected from the auction.

- from De Luca (2009:359)

In the central probe H2 was exposed for 16 m a stretch of via pasolata 6 m wide, USM 5 (see Figure 27), which runs from the South-West to the North-East (from an average altitude of -205.45 m to one of -204.59 m). Its axis seems to have determined the orientation of the buildings set on it, both those that emerged in H3 and those in H1, an orientation which, moreover, is consistent with the topographical layout of the city as can be observed from the East district. Ideally extending it the route towards this direction, in fact, the new paved road joins with the northern stretch of the cardo maximus (V1) near Area B, therefore classifying it as one of the decumani. On the opposite side, its route heads towards the Wadi Hamam pass which, in ancient times, was the main natural connection between the Lake and Western Galilee.

Stratigraphically, both the road and the structures facing it are covered by a whitish beaten ground, of small thickness, not attributable to any building and, in turn, covered by the surface layer US 4. In it, with late Roman ceramics, the following coins were collected: a prutah of 1st century BC, a Tyrense issue from 18 BC or 115 AD, a mint of Agrippa II for Nero from the mint of Caesarea Neronia (Philippi) from 67 AD and finally a fals from the Ayyubid period (12th-13th century AD) which dates the layer .

Observing the section of the walking surface, in particular the less dilapidated sections, such as the one to the west (see Figure 27), it is noted that it presents itself as a "donkey's back", with the bump on the central axis and the watersheds (30/35 cm difference in height) obtained at the edges, with a slope towards the East, against the crepidines raised in pseudo-isodome work. Of these, the best preserved sections are USM 28 (2.3 m) to the south and USM 30 (7.7 m) to the north. In correspondence with the crepidini, in fact, the facades of the buildings stand out, rising by a step, such as the one that develops to the south of USM 28 and to the west of USM 55 and, above all, like those to the north of USM 27, both to the West and East of USM 25. Between the cracks of the polygonal basaltic paving stones arranged in a tight manner and laid down on a bed of breccia and mortar, 2 coins of Alexander Janneus from the mint of Jerusalem (103-76 AD) were found. The ceramic finds on the pavement, to which is added a coinage of Trajan issued in Tiberias (98-117 AD), are overall late Roman. In an unspecified time the road was heavily restored with a casting of cement material mixed with gravel and shattered ceramic, very tenacious and compact (US 32), containing a coin of Alexander Janneus (103-76 BC) and a beaten coin of Trajan in Tyre (110-114 AD). The intervention aimed to integrate the areas already stripped of pavements and to bring the original convexity of the road surface back to level.

A deep sondage was dug into the road using an artificial hole (US 33; 1.20 x 1.60 m) dug from above in recent times, perhaps as a planting pit for a tree. In the West section the survey shows that the US 32 cement restoration reaches a thickness of approximately 60 cm. Here, incorporated into the concrete of US 32, there was a Tyre coin from 18 BC or 115 AD. In the filling of the cut (US 115) poorly dated materials were found, and in the preparation of the base, with late Hellenistic fragments, he also finds a piece of circular catillus of a rotary millstone in porous basalt (St 58), with a lateral appendix equipped with a hole for the wooden handle (Durante 2001, 77-78). The removal of paving stones in late antiquity may have been dictated by practical reasons: 1) to recover building material, given that paving stones have a surface perfectly smoothed by prolonged use; 2) to restore the functioning of the underroad canalization. In fact, in USM 5, both north of US 33 and north of US 52, it will be noted that the surviving paving stones retain, in their alignment, a continuous thread and that the covers of a canal (USM 61) invade the road area in the central-eastern sector of the probe. These are large basaltic slabs (up to 1.15 m long) which we found partially slipped inside a pipeline (see point b below).

- from De Luca (2009:362)

It has not been verified whether, as it would appear, the alignment of USM 59 square stones which, curving towards the East, reaches the well, is a further water branch. This structure, and also the others pertaining to the canal, were found to be covered by a whitish layer of weathering, US 54, below the surface level (US 4), rather friable and with many ceramic inclusions from the late Roman period.

To the west of the conduit and to the south of the decumanus no structures have survived (see Figure 30), with the exception of a sort of floor preparation, US 52 (approximately 3 x 3.5 m, at a height of -205.97 m), consisting from flakes, pebbles and basalt processing waste arranged flat in a layer of not very tenacious lime-based mortar where a coin of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) was also found. Since no significant nuclei of mosaic tiles were found at the same time, it is difficult to interpret this preparation as the bed of a mosaic, although it possesses the characteristics.

Furthermore, US 52 was also covered by a whitish calcareous layer, US 34 (see Figure 31), very compact (at the level of US 6 and US 54), and thick up to 40 cm. Some sections of US 34 were removed and inside there were a number of ceramic fragments, the most recent of which were late Roman and some coins including an autonomous issue from Ascalon (48-46 BC) and one from Tyre (98 - 85 BC).

Surrounded by US 52 there are two well-cut ashlars (60 x 20 cm), in line with the USM 35 structure, made up of 4 blocks (one of which is 1.3 m long) which is located further west. Since the two blocks and USM 35 are in turn flush with USM 28, it could well be the remains of a crepidine, comparable to the one well preserved along the eastern edge of cardo V2, and which here in ancient times one can imagine marked the southern limits of the roadway. Of the buildings that must have overlooked it, all that remains is a collapse, US 12, associated with the USM 55 wall which in plan view was hypothesized to reach the north-western structures of H1. Inside the US 12 collapse, mainly made up of medium-small and unworked stones, we note a basalt tray foot (St 55) and two coins, one of Herod Antipas minted in Tiberias (4 BC-39 AD) and a Roman provincial issue (perhaps from the 2nd century AD). The loosely aligned stones, identified under US 34 south of USM 35, are currently too disorganized to be related to a building .

- from De Luca (2009:363)

The collapse to the west of USM 31 (see Figure 33), included to the south by the road and to the west by USM 29, was called US 10 (2.10 x 3 m). It refers to a rectangular room (4 x 3 m) of whose façade only the foundations were found in depth. USM 31 has the appearance of a dividing wall, its thickness does not exceed 40 cm. and a prutah by Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) was found in the cracks of the proofs . Of the northern wall only a double-faced section (0.80 m) is visible near the cut of the section, which is at the corner with USM 29. In the central part of the USM 10 collapse, an alignment of ashlars belonging to an arch or a pillar, collapsed from West to East. The finds from the layer of disintegration of the collapse include late Roman ceramic fragments, with a prevalence of common table shapes, the intact upper element of a rectangular mill of the hopper and lever type (St 50 ) (Durante 2001, 78) found against USM 29 near the corner of the room and the following coins of: Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC), Aretas IV issued in Petra (9 BC-40 AD), Trajan of the mint of Rome (98-117 AD), Hadrian of the mint of Rome (119-122 AD), Trajan Decius-Volusianus of Caesarea Maritima (249-253 AD), Roman provincial mint (1-1 /2 III century AD), provincial Roman mint with oval male head countermark (perhaps 2nd century AD), provincial Roman mint with oval countermark le (II-1/2 to III century AD). The ground of the room, which can be reached by removing the collapse, should correspond to the support surface of the millstone, and thus be lower than road level.

The situation of the environments is formed by USM 25 (6 x 0.55 m, at an altitude of -205.73 m), USM 26 (4 x 0.50 m, at an altitude of -205 m), USM 27 (4 x 0.60 m, at an altitude of -205.76 m), and USM 29 (4.4 x 0.55 m, at an average altitude of -205.75 m). These are two rooms interconnected by the door in USM 26 and affected by a collapse, US 13, which is related to the USM 27 facade and which also occupies the passage space between the two (cf. Figures 34-35). The US 13 collapse, especially in the core near the South-West corner, is mainly made up of well-cut and also refined basaltic elements, typical of exposed curtain walls. The layer of decay that contains the collapse is distinguished by its white colour, its extreme compactness, its predominantly calcareous composition, and the ceramic inclusions from the middle Roman period and the beginning of the late Roman period, including many pieces of keeled pans of the Teg13 type (Pt 6959), and plates-pans of the Teg15, Teg16 and Teg17 types. Furthermore, the layer contained a Roman provincial issue from the first half of the 3rd century AD and a Tyrense coinage of Trajan (111-112 AD). Also in the upper interface, in contact with the US 4 surface layer, was a British Protectorate 1 mil piece (c. 1940).

For this building too, at the moment, the ancient walking surface has not been reached, but a small survey carried out in US 24 (whitish layer of decay with rubble in which the collapse sinks), near the façade wall USM 27, has allowed us to collect late Hellenistic-Ancient Roman material, including fragments of Herodian lamps (Luc2), soft stone jugs (Vas 1) and pots (Pent8, Pent10), which would appear to be indicative of levels of use prior to the collapse of US 13. Fragments of a similar chronology were also recovered under the collapse on the USM 27 wall. There, among the collapsed ashlars, it is possible to see the monolithic threshold of the entrance still in situ. Compared to the altitude of the roadway, this threshold, and even more so the floor level of the space, are at an appreciably lower altitude of up to 60 cm. Normally the opposite happens, although, in this case, the presence of USM 30 which rises one course from the road surface could have prevented water infiltrations, also averted by the conspicuous use of mortar and the studied slope of the external surfaces. Limited probing deep into the street revealed no traces of a previous road surface. The one carried out in the north-west end, in an area devoid of paving stones, instead revealed that the step of the USM 30 pavement has a solid foundation made of well-cut ashlars bound with mortars. West of USM 25 develops another large room (4 m deep and at least 3 m wide) in a state of collapse (US 36). Also in this case, the materials contained in the layer of decay, with a prevalence of rubble, contained sherds from the middle and late Roman period, including a coin from the mint of Caesarea Panias of Agrippa II for Titus (79-80 AD). At present, the structural links of these environments with those that emerged in the South-West sector of the H3 trench are not known, although they can be assumed by calculating their volumetric development (see Figure 36).

- from De Luca (2009:365)

The main wall alignment that emerged from the excavation is USM 8 which was exposed in the middle of the trench for a total stretch of 10.7 m (at an altitude between -206.21 m and -205.93 m). The wall is made up of regular rows of basalt ashlars, arranged alternately lengthwise and widthwise, with a central core of light binders for an average thickness of 60 cm. (cf. Figure 37,40). It was possible to verify that at least four courses with a regular and uniform horizontal trend survive. Towards the east the wall connects with USM 66, perhaps with USM 9 and with USM 48, built with a similar masonry technique. Towards the West, the USM 72 wall was doubled (or doubled?) and was linked to USM 70 and USM 68 was placed against it. It is therefore clear that it is a load-bearing wall, but it is not yet clear whether the rooms to the East and West are all part of the same building. Hidden under a stone of USM 8, 5.5 m from the southern corner, a storage room was discovered (see Figure 40) containing 18 coins which, in ancient times, must have been accessible from the eastern compartment. At a later time , in a nearby point, three other coins belonging to the same monetary deposit were found. The catalog of 21 pieces includes very contemporary bronzes, summed up due to prolonged use, originally beaten by the nearby autonomous cities between the 1st and the middle of the 2nd century AD, but which were put back into circulation after having been re-tariffed with a countermark still to be studied: a fine example of minting from Tiberias under Claudius (53 AD), one from Tyre (55 BC - 87 AD), two from Trajan, the one issued by Tiberias (99-100 AD) and the other by Sepphoris (98-117 AD), two by Marcus Aurelius issued in Gadara (161-180 AD) and perhaps in Abila (161-180 AD), one by Commodus in Nysa Schythopolis (182- 183 AD), one of Settimio Severo for Giulia Domna issued in Nysa Schythopolis (206-207 AD), seven of Elagabalus of which one was with a figure of the standing emperor (218-222 AD), three of the mint of Nysa Schythopolis (218-219; 220-221; 220-221), one from the mint of Antiochia ad Hippum (218-222 AD) and another from the mint of Petra (218-222 AD), five Roman provincial issues of 2nd-half of the 2nd century AD, two Roman provincial issues from the middle of the 2nd century AD, one from a mint of the Decapoli. It is hoped that a detailed study of the stamps will allow us to trace the emissary authority, perhaps opening up possible scenarios on the role of the city in the late Roman imperial military apparatus. At the moment, due to the context of discovery , the nest egg constitutes a decisive terminus post quem for fixing the date of destruction of the building, which roughly should be placed after the era of Diocletian (284-305 AD) who, with the fortification of the limes arabicus palestinensis, reorganized the territory militarily. This data is somehow supported by the monetary discoveries in the other sectors of the probe (the latest of which date back to the second half of the 3rd century AD) and by the study of dating materials, in particular by the ceramic forms typical of the century. III but which, in the region, are also attested in contexts that reach up to the century. IV.

The planimetric diagram relating to the rooms to the east of USM 8 (see Figure 37, 41) shows three rooms communicating with each other. The northern compartment is delimited by USM 8, USM 48, USM 47 (at the average altitude of -206.30 m) and is affected by the US 50 collapse (3.90 x 3.10 m). The collapse consists of two levels: an upper one, with large natural and rounded basalt boulders to the North-West, and a lower one, to the South, with parallelepiped-shaped ashlars arranged in a double row side by side with an undulating East-West/West-East towards the center of the room (see Figure 42). These are probably the results of a structural failure of wall pillars or the ruin of a double arch that fell from the key. When this occurred the door space in USM 48 had already been blocked by an array of rounded boulders. The USM 48 wall (at an altitude of -206.38 m) was initially made up of two pillars, one against USM 8 and the other against USM 47. A second building was added to the latter which reduced its opening from an original span of 1.60 m to a current one of 1 m. A prutah of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) was found between the cracks in the pillar .

The central room (4 x 3.9 m) is delimited by USM 8, USM 48, USM 47 and USM 9 and is also occupied by a collapse layer (US 11) approximately 80/90 cm high and disturbed only in the central part. The fragments collected in the calcareous layer of decay are from the late Roman period, as are some partially reconstructed forms found in the use levels of the environment, below the collapse. Among these we note an amphora (Pt 7804-7807) squashed into the wall niche (80x40 cm) of USM 47 (see Figure 43) corresponding to the typology of the Anfl4 "with high neck and curb at the base, with rounded rim and collar on the external side" (Loffreda 2008a, 127) which can be chronologically attributable to the middle and late Roman period. A coin of Probus (276-282 AD) was found on the collapse and one of Alexander Janneus (103-76 AD) from inside at -40 cm. from the shearing of USM 8, another issued by Tyre (93-196 AD) and a final one by Pontius Pilate for Tiberius (26-36 AD). The southern wall, USM 9 (at an altitude of -205.90 m), was tested for a height of four courses, equipped with ashlars alternately ordered at the head and at the edge and has a niche (80 x 440 cm), similar to that of USM 47, defined by long (up to 1 m) and wellcut basaltic blocks. The passage that leads from this room to the smaller one (2.30x3.80 m) further south is not yet entirely clear and is, like the others, blocked by a collapse (US 49). The doorway (span of 70 cm) is, in fact, occupied by some cut blocks of the roofing type (more than 1 m long), near a position arranged from South-West to North-East of elements similar lithics (see Figure 46).

This environment is closed to the east by the southern stretch of USM 47, preserved only at the construction level (at an altitude of -206.55 m) and probably stripped when the building visible in the south-east corner of the probe was built (cf. Figure 41). The latter building, with the corner of USM 76 (2 x 0.60 m, at a height of -206.10 m) and USM 75 (2.80 x 0.65 m, at a height of -206.15 m ) was in fact set to the detriment of the structures of the southern compartment during the ancient Arab period. The ceramic materials collected above the US 67 collapse, south of the southern wall of the room, refer to this date, including parts of an amphora with a light body and a high ribbed neck (Anf49), known elsewhere from contexts close to the earthquake of 749 of the current era. In trench H4 it is assumed that the structure of the Arab era to which USM 75 and USM 76 belong continues, given that, under the surface layer (US 317) a level of disintegration begins to appear containing numerous single-handled vents of the Anf50 type, a typology referable to the Khirbet el-Mefjar factory and well known to us for the many specimens found in M31 (infra). USM 66 (at an altitude of -206.03 m) differs from the other walls of the southern environment due to the rougher execution technique due to the irregularity of thickness (from 60 to 70 cm) and the use of drafts also calcareous and only coarsely faceted.

Under the collapsed US 67 there is an ancient building to which two discoveries belong: numismatic minds of Alexander Jannaeus (Jerusalem 103-76 AD) and of Demetrio III (Seleucia Piena 96-87 BC).

- from De Luca (2009:369)

- from De Luca (2009:369)

First of all, what stands out is the attempt, which cannot be better defined, to reinforce USM 8 with heterogeneous stones, some of which are cut, placed against its western face (see Figure 38). This intervention did not find a logical explanation during the excavation, unless we hypothesize a false reuse of USM 8 after the total collapse of the buildings to which it belonged. Given the total absence of levels above our US 7, the available data do not currently allow us to say this with certainty. On the other hand, it is clear that an imposing and well-finished building work, USM 72 (1.35 x 3.15 m, at an altitude of -206.31 m), flanks the northern section of USM 8 on the western side. In the lower part of the smaller portion of this structure you can see large and well-finished blocks of basalt, at an altitude of -206.57 m, which could form part of a staircase to access the roof or upper floors. If this were the case, what is visible of USM 72, which was also built with the use of excellent mortars, would constitute its basic platform.

Crushed under the collapsed US 73, west of the USM 72 platform, south of USM 84 and to the east of USM 71 it was possible to identify a good assortment of complete ceramic forms (see Figure 44). Some have been recovered and completely restored and thus provide a useful indicator for establishing the moment of collapse. In particular, the amphora specimen Pt 6133 should be remembered here, typologically similar to Anfl4 which is possible to have "its origins in the advanced phase of the ancient Roman period" (Loffreda 2008a, 127) and which was also in use in the Roman period late hand; the pan plate Pt 6132, close in shape to the Teg16 and Teg17 types - although it does not have the grooves on the rim -, both dating back to the mid-3rd century. and the late 4th century. A.D; and the pot Pt 6207 with thin walls and a globular body with slightly differentiated grooves on the shelf rim, of the Pent12.2 type, dated approximately between the mid-1st and mid-4th century. AD (Loffreda 2008a, 186-187).

To recover these materials, the US 73 collapse layer was excavated at a depth of 1 m below the prominent walls USM 84, USM 72 and USM 71. USM 84 is too little exposed (about 2 m, at a top altitude of -206.36 m): its thickness is not known but it is built with beautiful masonry joined by mortar. USM 71, on the other hand, is summarily built with the outlines of the irregular rows of the upper part resting on a 30 cm-high foundation tooth and protruding 20 cm. three courses lower. Apparently USM 71 gives every impression of being a posthumous infill between the US 18 pillar to the south and the USM 84 wall to the north.

The USM 18 pillar (at an altitude of -206.10 m), on the other hand, is built by alternating the head and cutting of the squared basalt ashlars and binding them with tough lime-based mortars, obtaining a horizontal section in the shape of "T" (see Figure 38). This means that it had a counterpart on the East, South and West sides. On axis, at 1.65 m towards the West, there is the USM 85 structure, just intercepted in the cut of the section. To the east, at a distance of 1.10 m, there is the southern head of the USM platform 72. To the south, to 3.40 m, the USM 22 pillar was brought to light (at an altitude of -206.06 m), protruding from the wall 45 cm. This large distance is interrupted, exactly in the middle, by a column (USM 19) with a diameter of approximately 50 cm. (at an altitude of -206.17 m), cut into the basalt and smoothed with a chisel tip (see Figure 45). It is clear that the pillars and column supported a system of archivolts. Moreover, the entire US 21 collapse, which unfolds neatly to the East and West of the USM 18-19-22 axis, contains dozens of arch segments, many with trapezoidal sections, in primary position. As regards the remaining elements, they are mostly, in 80% of cases, worked ashlars. Even the US 82 collapse (2 x 2.6 m) in the North-West corner of the trench, upon superficial analysis, appears to be mainly made up of wellcut ashlars. Among them there were also pieces of a basaltic pulvino (or a shelf?) with an oblique section smoothed with a chisel tip and a coinage from Tyre (93-196 AD).

While it has not yet been possible to identify the corresponding supports for USM 19 along the East/West axis within the very thick collapse, it is however possible to see that the USM 22 pillar, which has a horizontal "L" shaped section, finds a counterpart in a square pillar which constitutes the eastern head of USM 23 (at an altitude of - 205.80 m) at approximately 1 m away. In turn, at a distance of 1.50 m, the western head of USM 23 (at an altitude of -205.75 m) also consists of a pillar of approximately 55 cm. sideways. The intercolumniation was infilled by a lower masonry than the pillars, due to the installation technique and quality of the construction material. Between the USM 22 and USM 8 pillars to the east, only by digging in depth was it possible to trace the USM 70 wall (2.20 x 0.60 m, at a height of -206.30 m), of which only the foundation level.

Among the materials collected within the US 21 collapse, together with much common ceramic of the Middle and Late Roman typologies, we note a basin with thick walls and rough body (Pt 8068), the trilobed leaf-shaped attachment of a bronze handle (Mtl 22) and the following coins: of Herod the Great (40/37-4 BC), of Tyre (18 BC-115 AD), of Trajan (Caesarea Maritima 98-117 AD) and a Roman provincial issue of the first half of the 3rd century AD. The pillars USM 22 and USM 23 act as abutments for a door that originally led into a southern room, which is now closed to the south by the USM 68 wall. USM 68 has only been partially exposed (3 m, 60 x 0.60/0.90, at a height of -205.73 m), however it is clear that due to its layout, thickness and approximate construction technique, although with the use of lime mortars, it is a completely different from the H3 load-bearing walls described here. The continuation of the excavation will allow us to establish its chronology and any structural connections with the buildings in the North-West sector of H2 (see Figure 36).

The US 69 collapse proved to be quite tampered with, particularly in the eastern sector (see Figure 46). This made it possible to descend into depth here (at an altitude of -206.62 m) and intercept, under a very compact limestone surface, the remains of an older, inclined and curvilinear position containing long basalt slabs which respond to the characteristics of hedging balatas and which could indicate a collapse level in phase with that of H1 (US 91-94).

Similarly, the US 83 layer is somewhat inconsistent, with dark earth and loose stone, under an accumulation of rounded natural boulders. From the bottom of the excavation, at the foot of the West pillar of USM 23, a leaden weight (Mtl 21) was found with, in a cartouche, the iconography in relief of the Phoenician deity Tanit (see Figure 47). This is one of the rare examples of the discovery of this class of materials in a stratigraphic context. Another very important specimen of an inscribed lead weight from Magdala is known from the antiques market (Qedar 1986-1987; Stein 2002). A third exagium from a later period was found by us in the port area of the site. The Phoenician weight measures 3.6 x 3.1 cm, weighs 53.75 g and has already been published by B. Callegher in the Quaderni Ticinesi di Numismatica e Antichità Classiche (Callegher 2008). The author concludes his exclusive speech assuming that "the weight discovered in Magdala is a local production" and rather considered its arrival and use on site following some merchant in connection with the Phoenician cities of the coast. "Moreover - writes Callegher - the study of monetary discoveries has made it possible to clarify that towards the end of the 2nd century BC and the first half of the 1st century AD a vast territorial area was formed, including Upper Galilee, in which nominal in copper minted following the metrology of the city of Tyre. Having said this, the square weight in lead [...], for the iconography can certainly be linked to the Phoenician types of Arado and a similar affinity suggests a consequent metrological connection. It is therefore conceivable that in the Upper Galilee, standards specific to the Phoenician cities or even in use in the area between Tiberias and Magdala were followed for weighing operations, and that only starting from the 1st century did they begin to be gradually supplanted by metrology of the Roman Empire. At the time of Agrippa II, however, the transition to the Roman pound had not yet occurred, as can be seen from the two weights of the agoranomoi Rufus/Iulius and Gesaìa/Animo, both of which have no relation to the standard of the pound (327.45 gr.) and of the ounce (27.29 gr.)" (Callegher 2008, 329).

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

eastern portico including square F18 (units 3 and/or 4)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations Color Code

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci) De Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci) De Luca and Lena (2014)

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and Fclick on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab Used with permission from from biblewalks.com |

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008) JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer De Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011) De Luca and Lena (2014) |

|

|

Areas H1, H2, and H3

Plate 6

Plate 6Plan of excavation areas H1, H2, and H3, at the end of the 2007 season of the Magdala Project (S. De Luca—A. Ricci; relief from M. Forgia, A. Faggi, and B. Stern). De Luca (2009

Plate 7

Plate 7Magdala/Taricheae, Area H1. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM (S. De Luca—M. Forgia). De Luca (2009

Plate 8

Plate 8Magdala/Taricheae, Area H2. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM (S. De Luca—A. Faggi). De Luca (2009

Plate 9

Plate 9Magdala/Taricheae, Area H3. Survey of the wall structures and collapses with indication of the main US and USM (S. De Luca—B. Stern). De Luca (2009 |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8General photo of Area H1 at the end of the excavation. Towards the West (D. Zanetti © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 25 (top)

Fig. 25 (top)General photo of Area H2 at the end of the excavation. Towards the East (D. Zanetti © Magdala Project) Fig. 26 (bottom) Aerial photo of Area H2 at the end of the excavation. (Skyview, © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39Aerial photo of Area H3 at the end of the excavation. (Skyview © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28Excavation documentation of Area H2 South East sector. Detail of the covered conduit USM 60-61-116 under the paved road USM 5. Towards the North (D. Zanetti © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 30

Fig. 30Excavation documentation of Area H2 South East sector. On the left: behind the covered conduit USM 60-61-116, you can see the US 59 alignment, the US 52 floor preparation, covered by the US 34 layer. On the right : remains of the paving of the USM 5 street. Towards the West (D. Zanetti © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 35

Fig. 35Excavation documentation of Area H2 North West sector. Detail of the particular elements of the US 13 collapse, in the US 24 destruction layer, against the USM 17 façade wall. Southward (Skyview © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009)

Fig. 42

Fig. 42Excavation documentation of Area H3 Northern sector. Detail of the collapsing structures USM 50, near USM 47 on the left, and USM 48 behind. Towards the South. (D. Zanetti © Magdala Project) De Luca (2009) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig.s 4 and 10 of de Luca and Lena (2014)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig.s 4 and 10 of de Luca and Lena (2014)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

eastern portico including square F18 (units 3 and/or 4)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the Harbors Structures. Magdala Project 2007–2011 Excavations Color Code

Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci) De Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Schematic Plan of the Byzantine Harbor of Magdala (Adapted from Raban 1988, fig. 7). Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project 2011–2012 (S. De Luca – A. Ricci) De Luca and Lena (2014)

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and F

Aerial View of Areas C,D, E, and Fclick on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab Used with permission from from biblewalks.com |

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Elevation and Sections of the Hasmonean Mooring Place and of the Early Roman Inner Basin, with mooring stones (MS 1 and 4) in situ. Courtesy of S. De Luca © Magdala Project (S. De Luca 2008) JW: See units 3-4 to the left of middle drawing (under F18) overlain by an apparent collapse layer De Luca and Lena (2014)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20Geological Space-Time Depositional Evolution Scheme of the Harbors of Magdala–Taricheae. Courtesy of G. Sarti, University of Pisa © Magdala Project – University of Pisa (G. Sarti 2011) De Luca and Lena (2014) |

|

|

Avshalom-Gorni, D. and Najar, A. (2013) , Migdal, Hadashot Arkheologiyot Volume 125 Year 2013

De Luca, S. , (2008) Magdala Project 2007, Notiziario SBF. A.A. 2006/2007 (Jerusalem 2008) in Italian

de Luca, S. and Lena, A, (2014), The Harbor of the City of Magdala/Taricheaeon the Shores of the Sea of Galilee, from theHellenistic to the Byzantine Times. New Discoveries and Preliminary Results in

S. Ladstätter – F. Pirson – T. Schmidts (Hrsg.), Harbors and Harbor Cities in the Eastern Mediterranean, BYZAS 19 (2014) 113–163

Lena, A. (2013) Magdala 2008 Preliminary Report Hadashot Arkheologiyot v. 125

Loffreda S. (2008a). Cafarnao VI: Tipologie e contesti stratigrafici della ceramic (1968–2003). Milano.

Loffreda S. (2008b). Cafarnao VII: Documentazione grafica della ceramica (1968–2003). Milano.

Loffreda S. (2008c). Cafarnao VIII: Documentazione fotografica degli oggetti (1968–2003), Milano.

Magdala at BibleWalks.com - lots of high resolution photos

Magdala.org