Khirbet Wadi Hamam

Aerial View of Khirbet Wadi Hamam on govmap.gov.il

Aerial View of Khirbet Wadi Hamam on govmap.gov.ilClick on Image to explore this site on a new tab in govmap.gov.il

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet Wadi Hamam | | |

| Hamaam | Hebrew | חַמָּם |

| Horvat Veredim | Hebrew | |

| Hamaam | Arabic | حمام |

| Mazraʿat Mugr al Hamam | Arabic | |

| Khirbet el-Wereidat | Arabic | |

| Wadi Hamam | Arabic | |

| Migdal Zabaʿayya ? | Aramaic | |

Khirbet Wadi Hamam near Hamaam

was first settled in the Hasmonean period around the early first century BCE

reaching

a peak in terms of size and prosperity in the Early Roman period, when large-scale infrastructural

and building projects were carried out.

(Uzi Leibner)

Archaeological evidence for a severe decline in the settlement surfaces in the mid-fourth century,

when most of the village was abandoned. The latest stratified remains at the site date to the last

decades of the fourth century, and village life seems to have ceased entirely at the end of that

century or in the early fifth.

(Uzi Leibner)

- Orientation Map from Uzi Leibner

- Fig. 1.5 Aerial photo showing

Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam and surroundings from Leibner et al. (2018)

Fig. 1.5

Fig. 1.5

Aerial photo of the British Royal Air Force showing Kh. Wadi Ḥamam and its surroundings; note the Beduin huts in the foreground, on both sides of Wadi Arbel (Photo ID 5141, January, 4, 1945; courtesy of the Aerial Photos Archive Digitizing Project, The Center for Computational Geography, The Dept. of Geography, The Hebrew University (2010).

click on image to open in a new tab

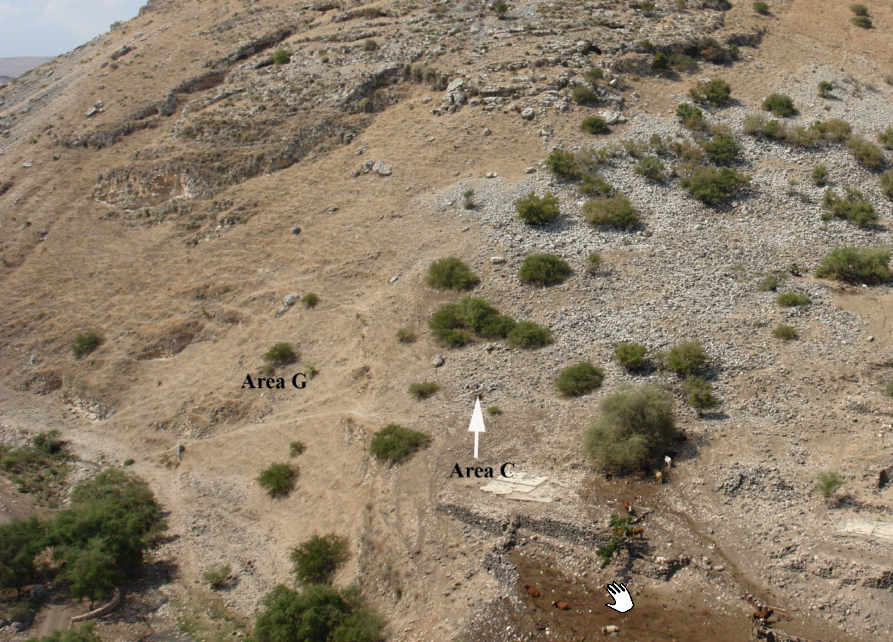

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 6.61 Aerial view of Area

C prior to excavation from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Khirbet Wadi Hamam in Google Earth

- Khirbet Wadi Hamam on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 1.5 Aerial photo showing

Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam and surroundings from Leibner et al. (2018)

Fig. 1.5

Fig. 1.5

Aerial photo of the British Royal Air Force showing Kh. Wadi Ḥamam and its surroundings; note the Beduin huts in the foreground, on both sides of Wadi Arbel (Photo ID 5141, January, 4, 1945; courtesy of the Aerial Photos Archive Digitizing Project, The Center for Computational Geography, The Dept. of Geography, The Hebrew University (2010).

click on image to open in a new tab

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 6.61 Aerial view of Area

C prior to excavation from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Khirbet Wadi Hamam in Google Earth

- Khirbet Wadi Hamam on govmap.gov.il

- Map of excavation areas

from Uzi Leibner

- Map of excavation areas

from Uzi Leibner

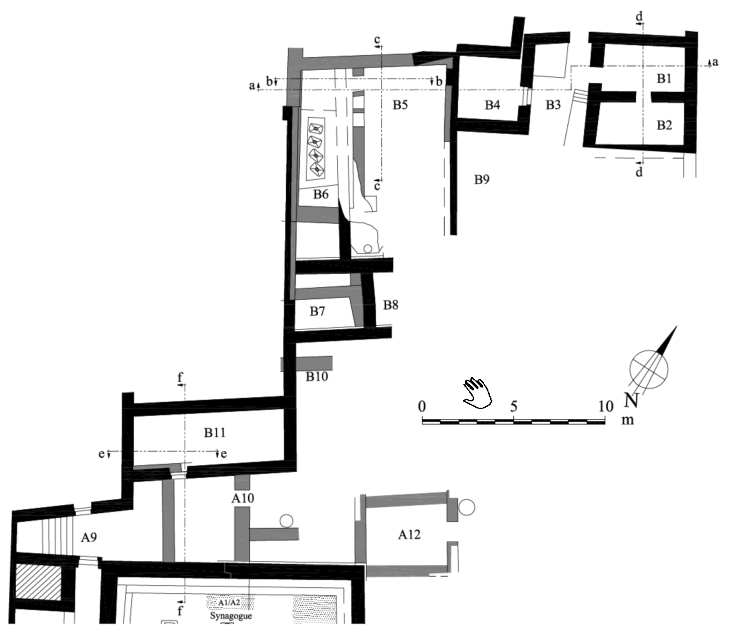

- Fig. 1.8 Block plan of Areas

A, B, and C from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.8 Block plan of Areas

A, B, and C from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.2 Aerial view of the

synagogue area after excavations from Leibner et al. (2018)

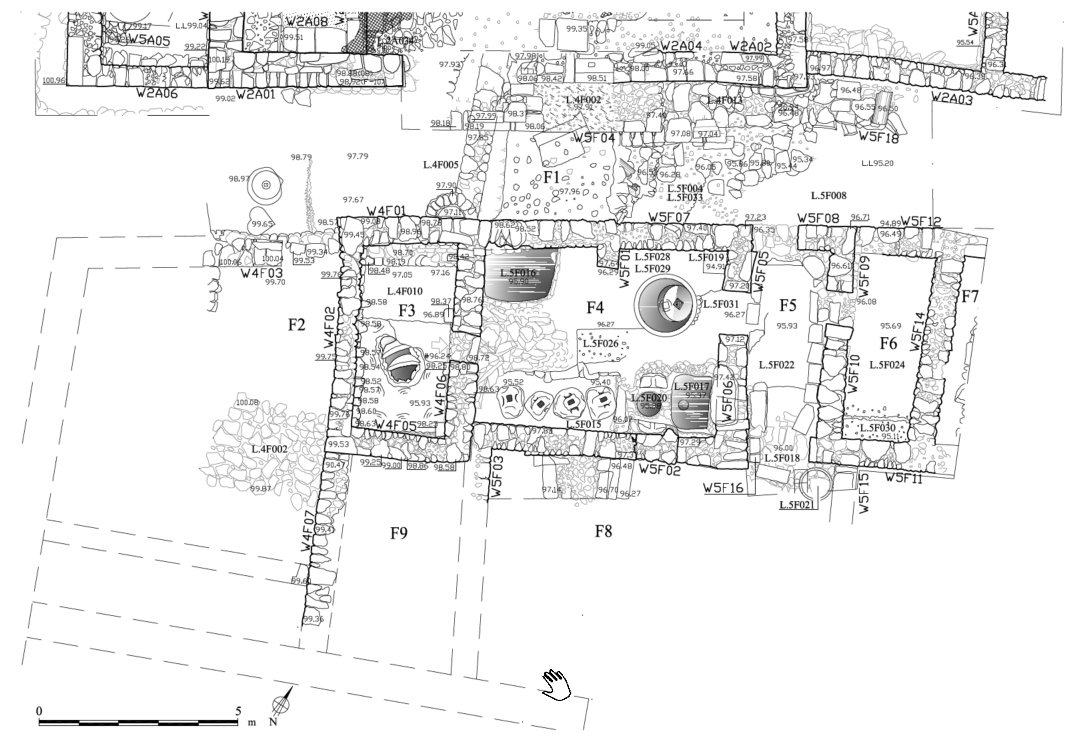

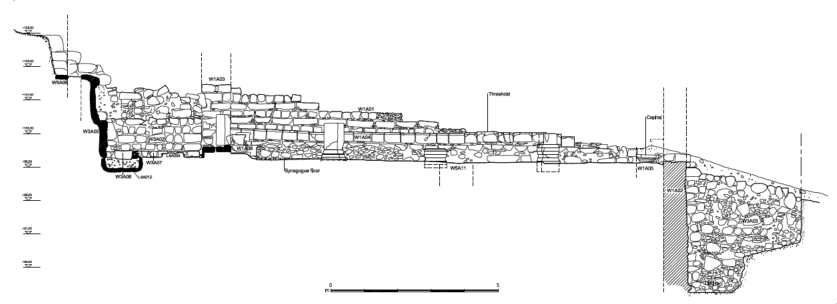

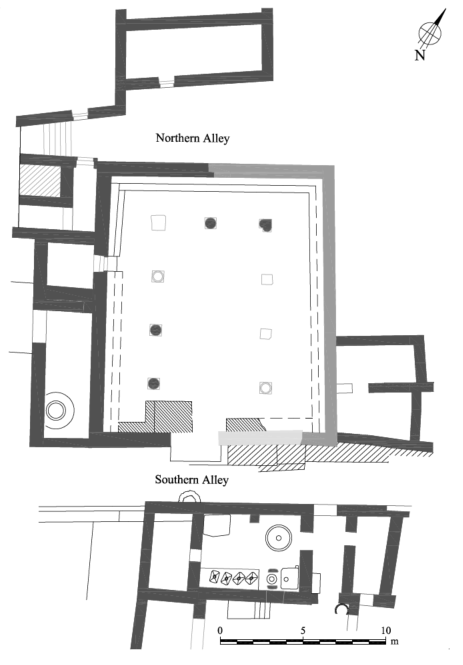

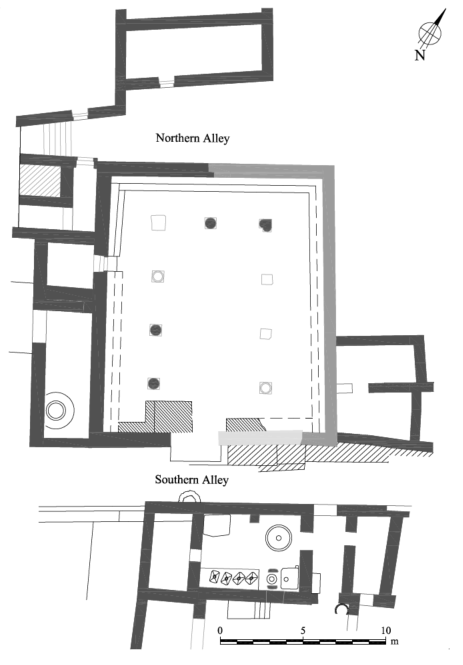

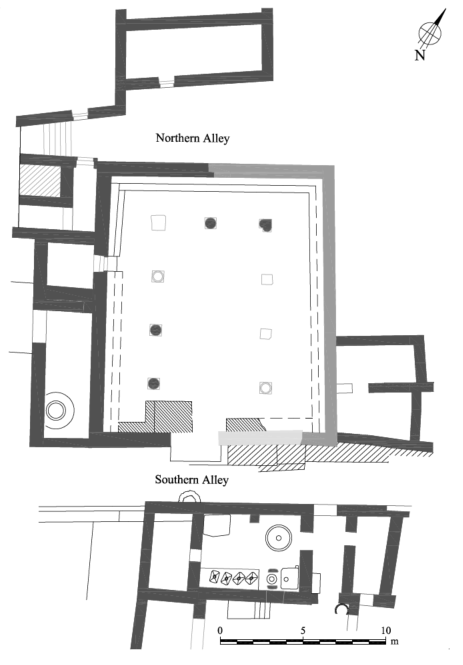

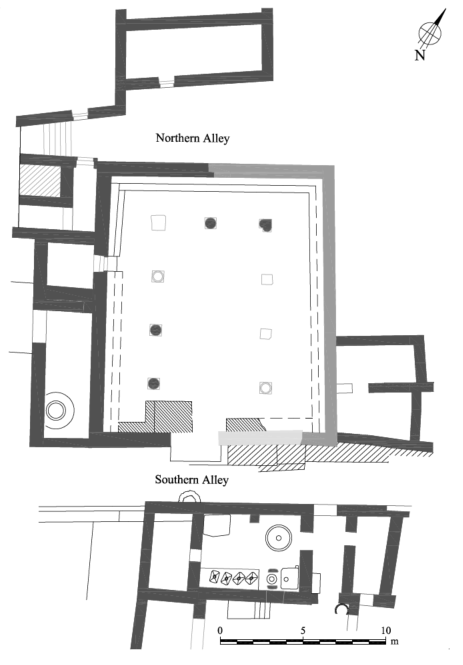

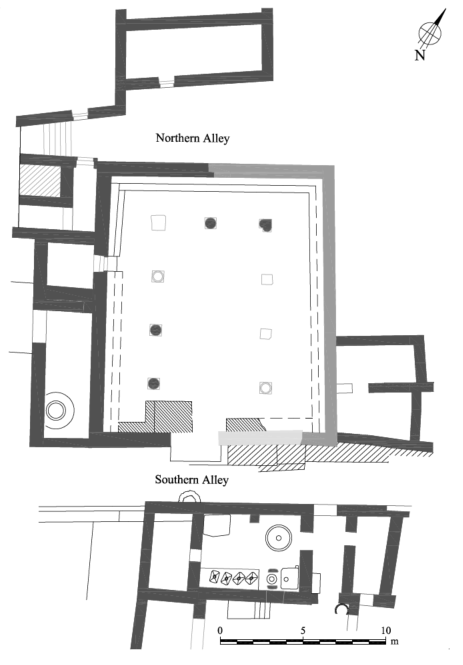

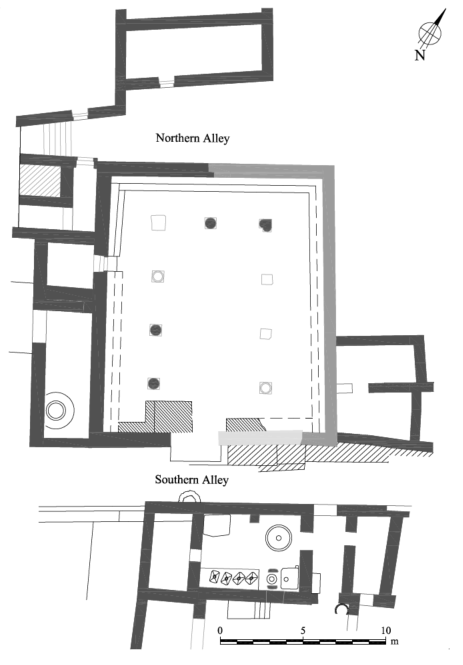

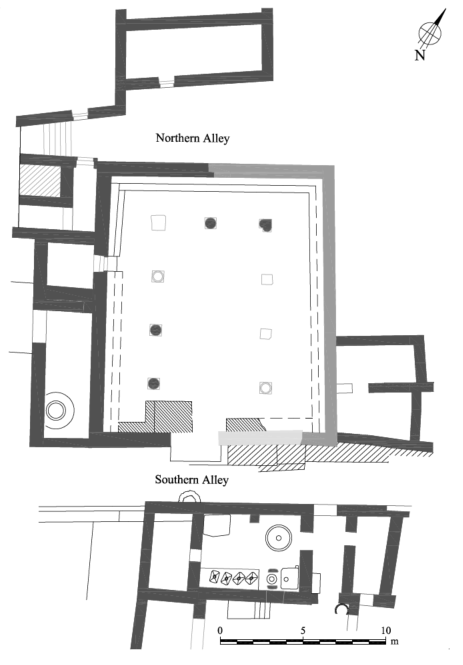

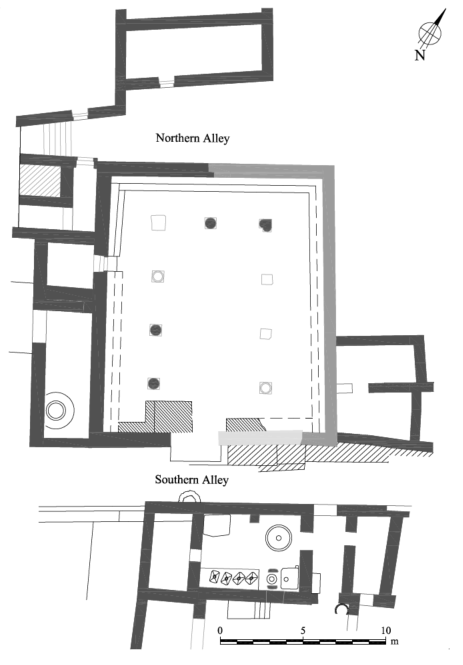

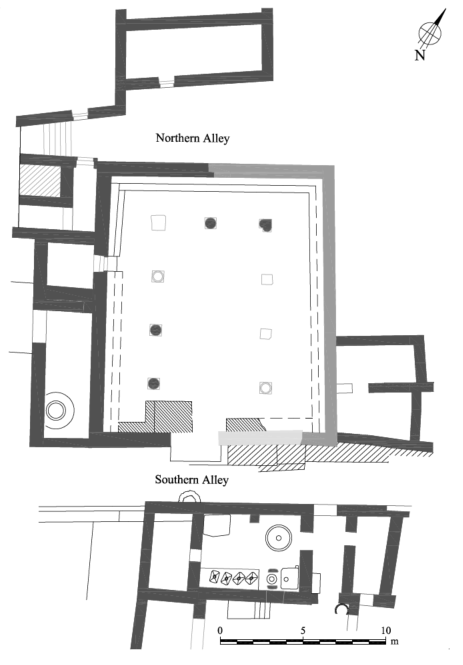

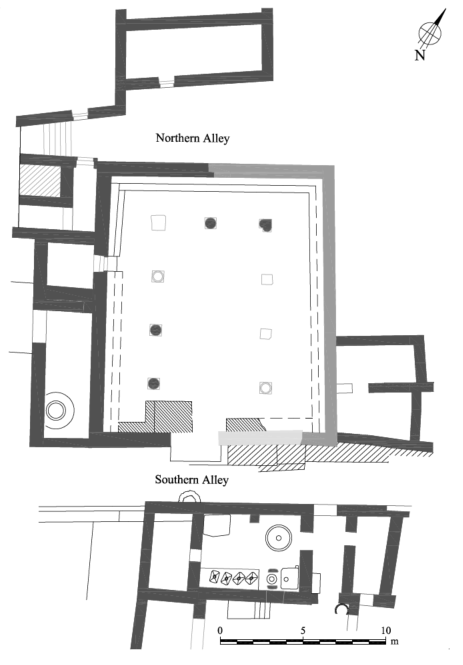

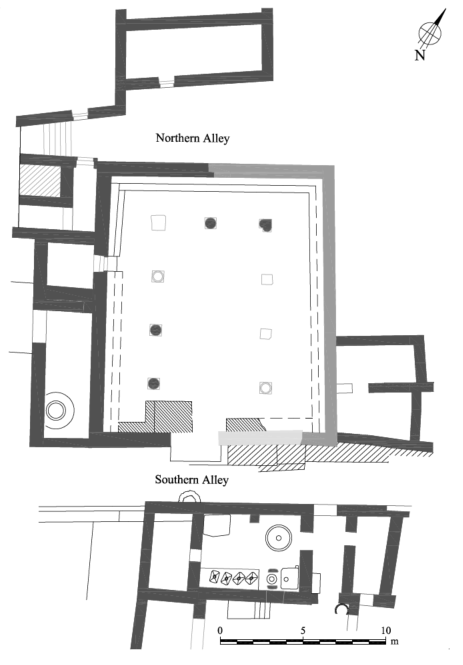

- Fig. 2.4 Block plan of Synagogue

II and surrounding Stratum 2 structures and alleys from Leibner et al. (2018)

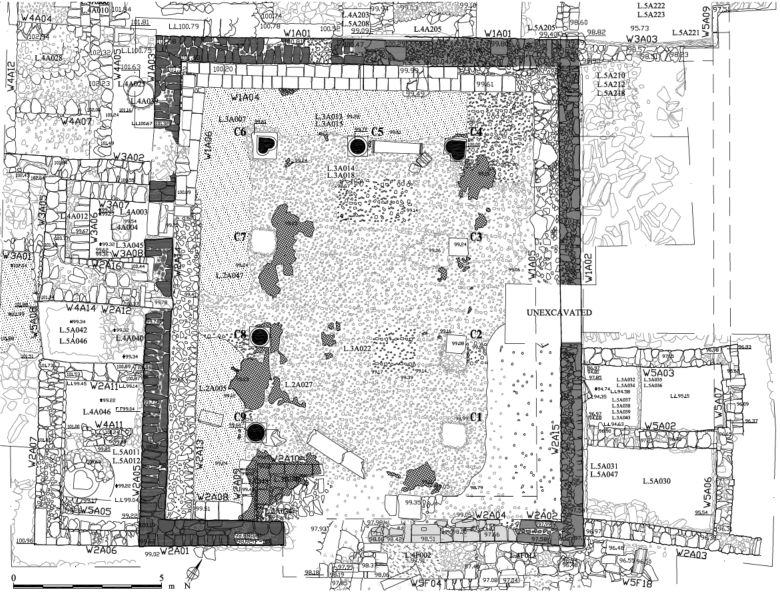

Fig. 2.4

Fig. 2.4

Block plan of Synagogue II and surrounding Stratum 2 structures and alleys

- black: surviving remains of Synagogue I

- dark gray: walls constructed in Synagogue II

- light gray: repairs in Sub-Phase Ilb

- raster: retaining wall built on the southern alley

click on image to open in a new tab

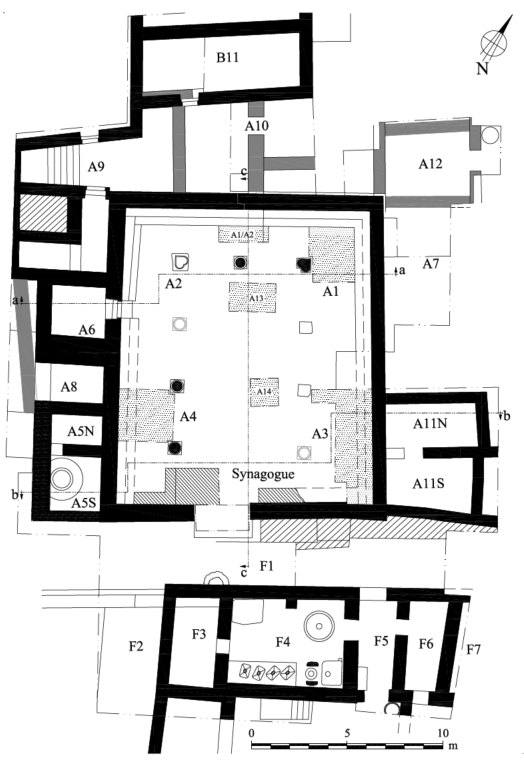

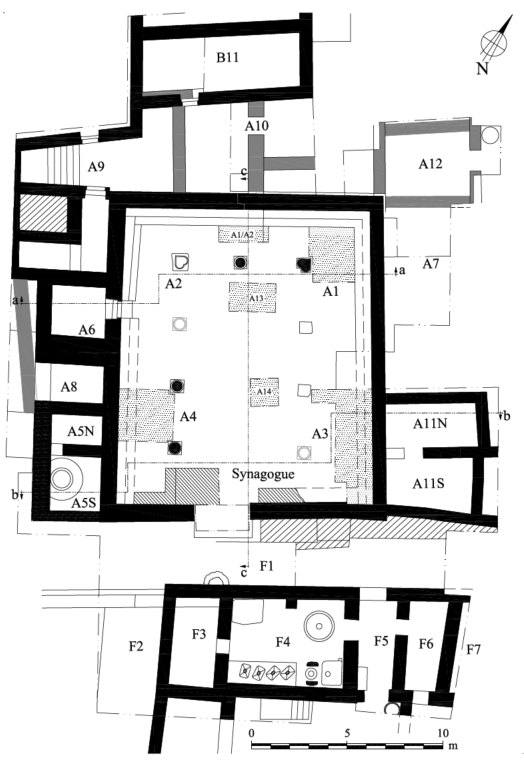

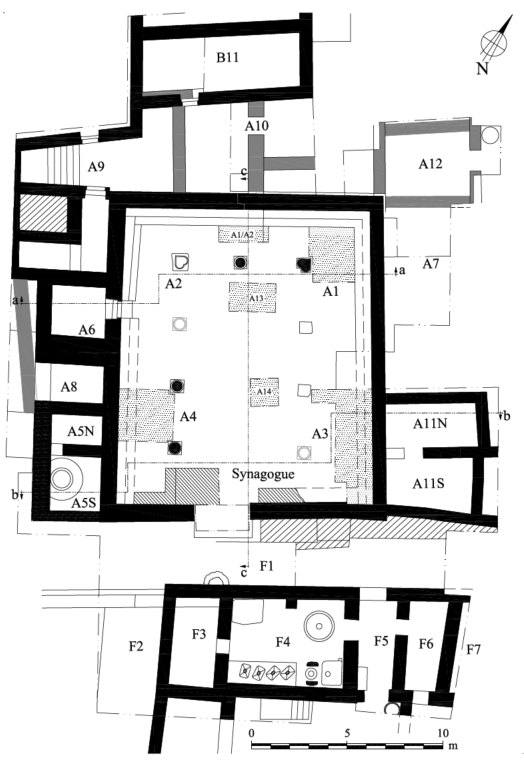

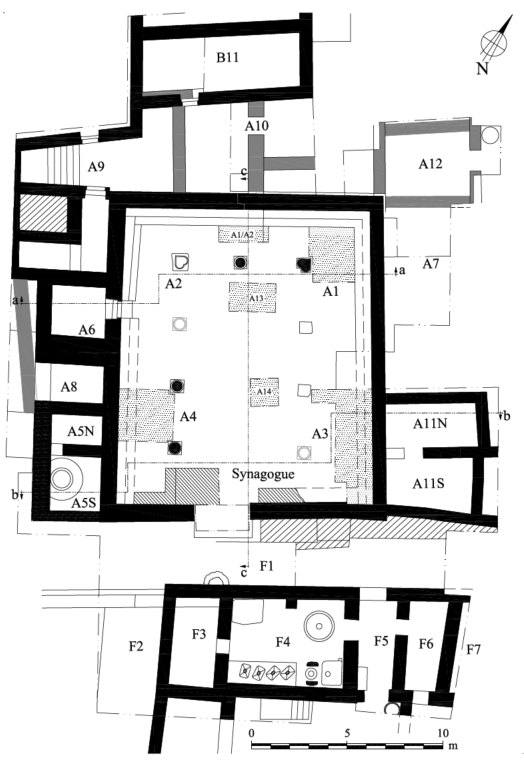

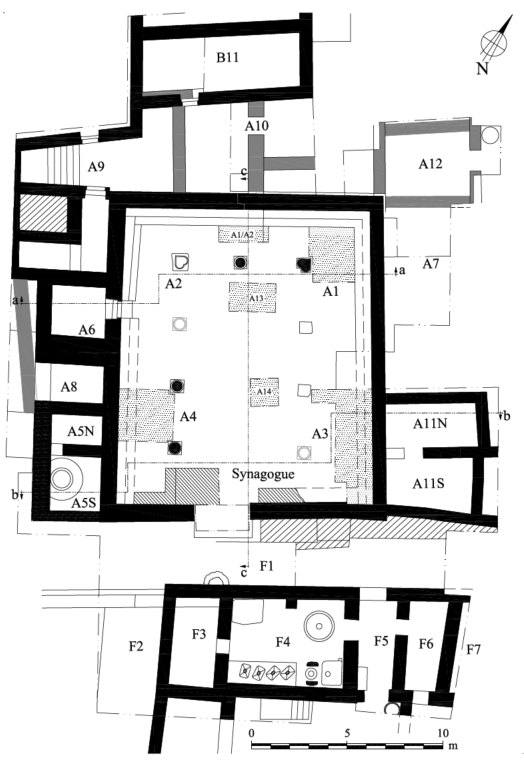

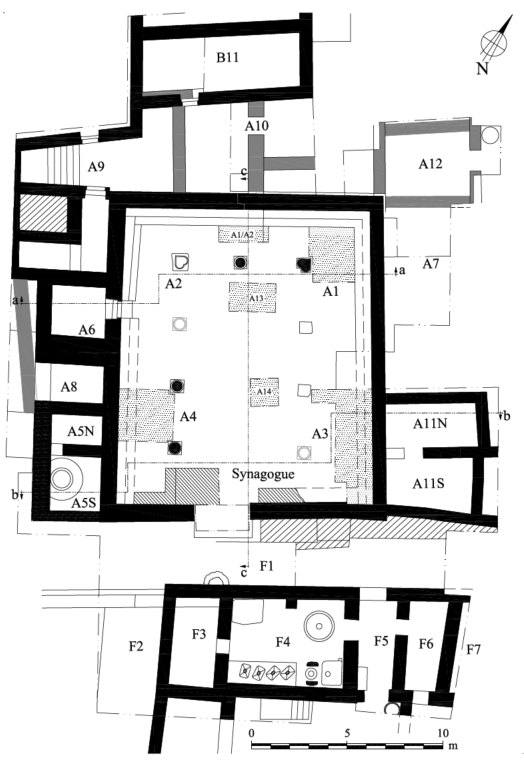

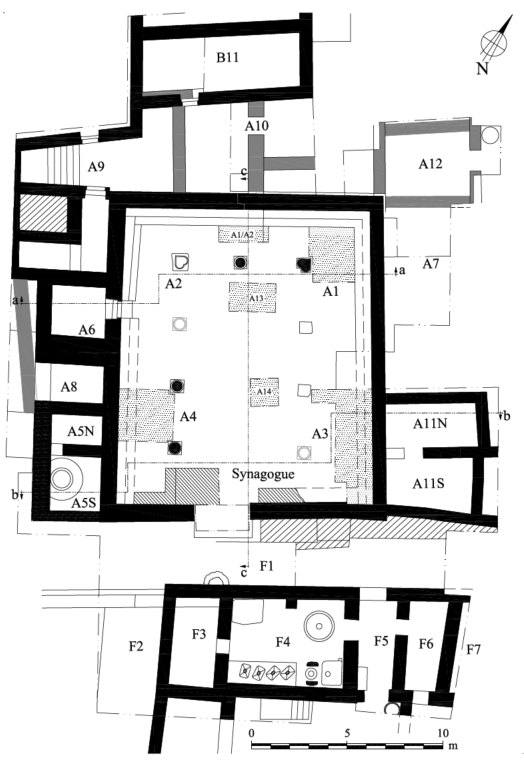

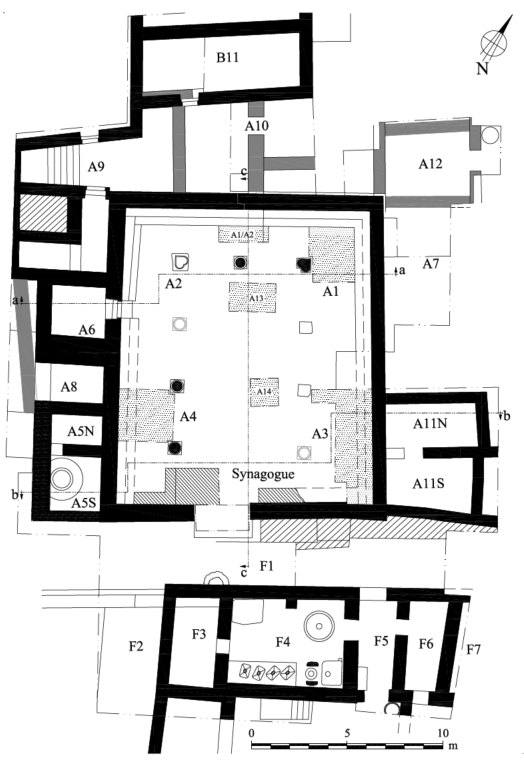

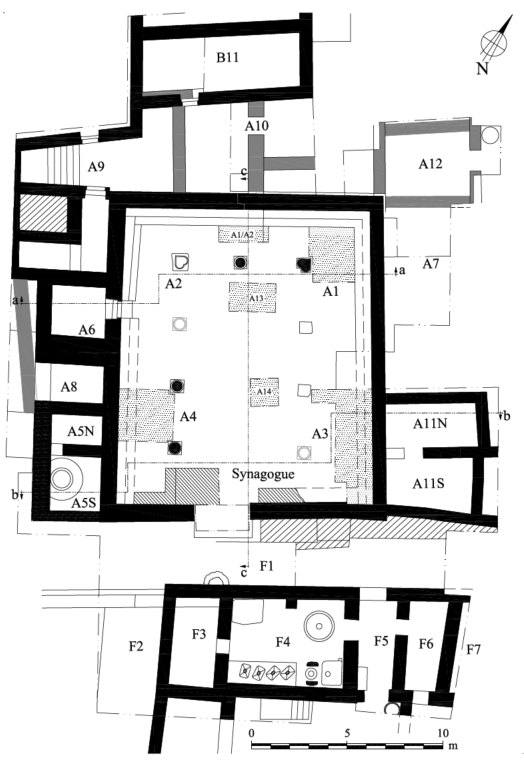

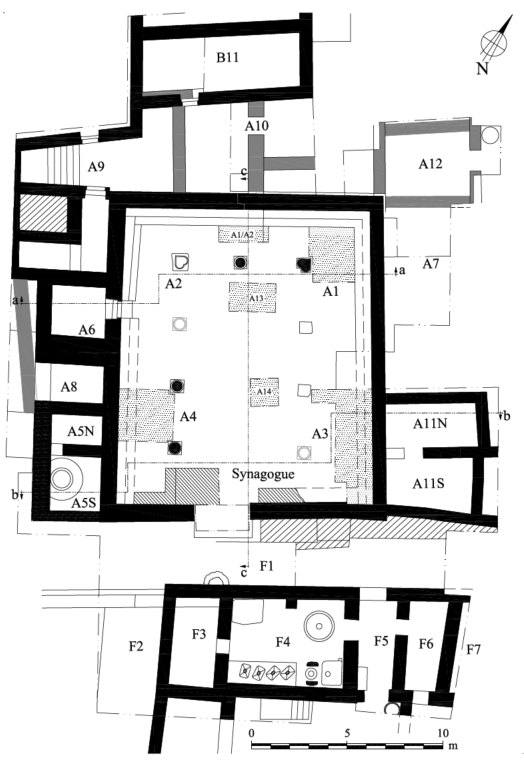

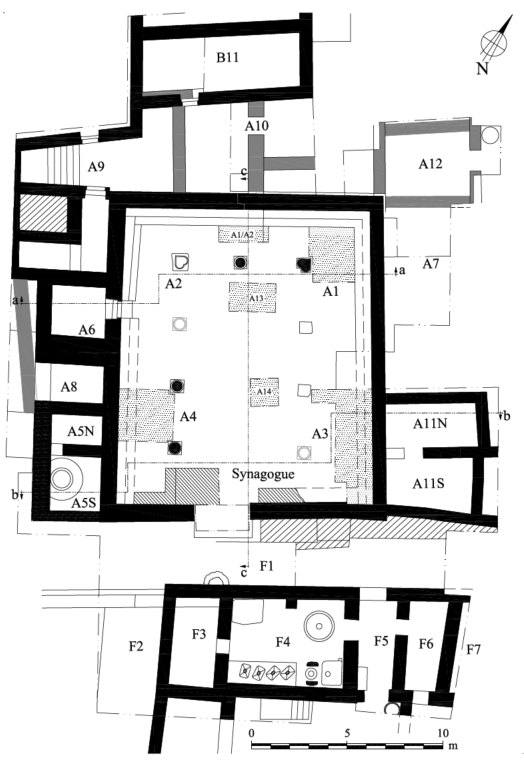

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 2.5 Block plan of the

synagogue showing the excavation areas (A, B, F), units, soundings and the major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

Fig. 2.5

Fig. 2.5

Block plan of the synagogue (in black) showing the excavation areas (A, B, F), units, soundings (dotted raster) and the major section lines through the building

- lined raster: Sub-Phase Ilb

- gray: Stratum 3 walls

- soundings: dotted raster

click on image to open in a new tab

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 2.7 Detailed plan of

the synagogue showing wall and column numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.2 Aerial view of the

synagogue area after excavations from Leibner et al. (2018)

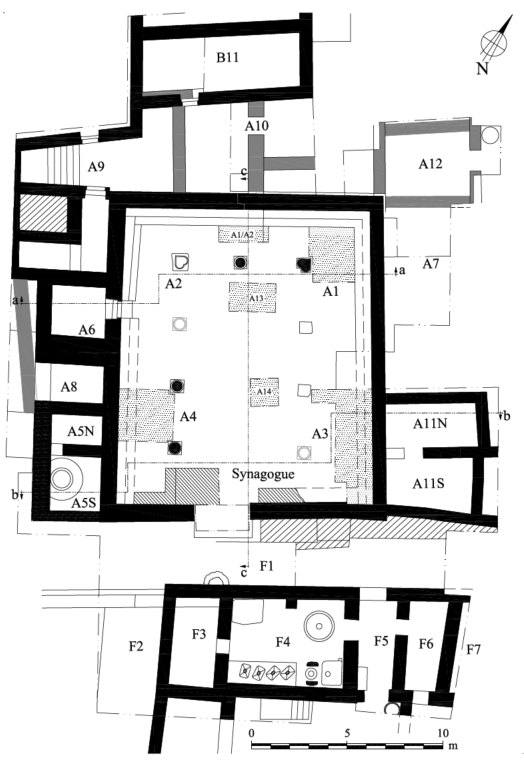

- Fig. 2.4 Block plan of Synagogue

II and surrounding Stratum 2 structures and alleys from Leibner et al. (2018)

Fig. 2.4

Fig. 2.4

Block plan of Synagogue II and surrounding Stratum 2 structures and alleys

- black: surviving remains of Synagogue I

- dark gray: walls constructed in Synagogue II

- light gray: repairs in Sub-Phase Ilb

- raster: retaining wall built on the southern alley

click on image to open in a new tab

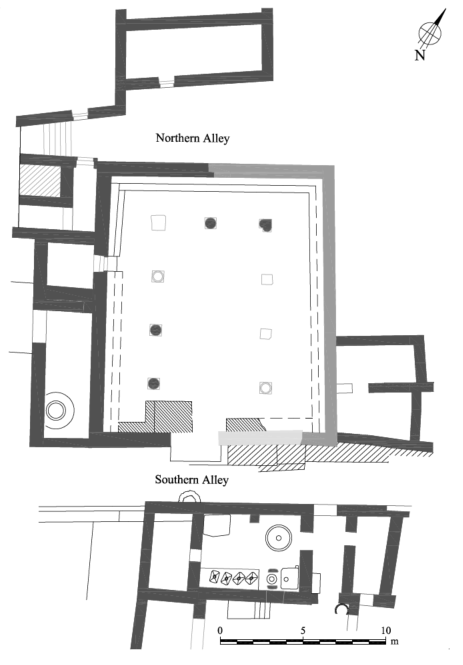

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 2.5 Block plan of the

synagogue showing the excavation areas (A, B, F), units, soundings and the major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

Fig. 2.5

Fig. 2.5

Block plan of the synagogue (in black) showing the excavation areas (A, B, F), units, soundings (dotted raster) and the major section lines through the building

- lined raster: Sub-Phase Ilb

- gray: Stratum 3 walls

- soundings: dotted raster

click on image to open in a new tab

Leibner et al. (2018) - Fig. 2.7 Detailed plan of

the synagogue showing wall and column numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.4 Aerial view of Area B

at the end of the 2011 season from Leibner et al. (2018)

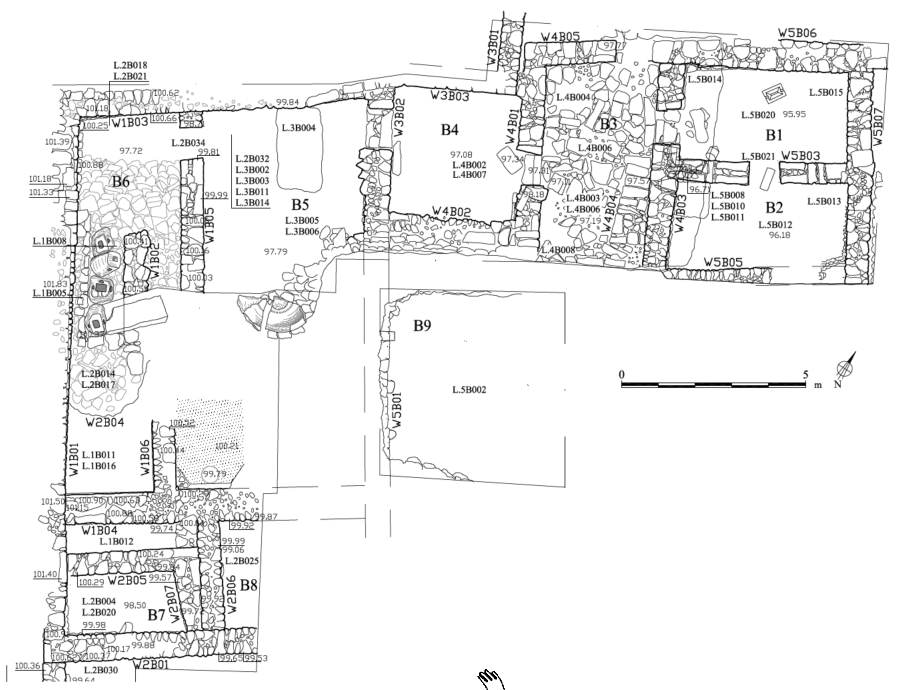

- Fig. 6.1 Block plan of Area B

showing the excavation units and the major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.2 Detailed plan of the

northern part of Area B showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.4 Aerial view of Area B

at the end of the 2011 season from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.1 Block plan of Area B

showing the excavation units and the major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.2 Detailed plan of the

northern part of Area B showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

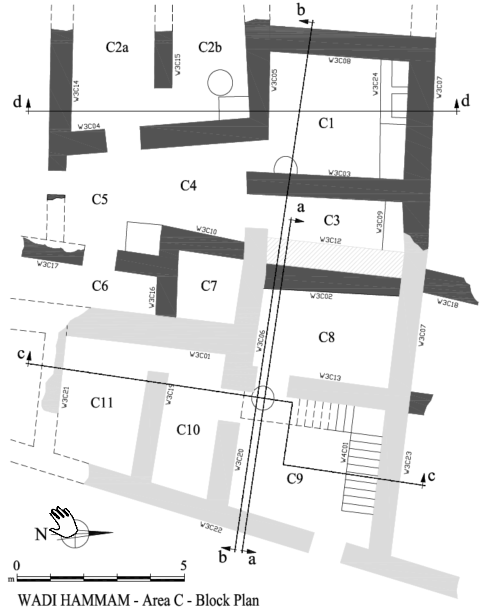

- Fig. 6.63 Detailed plan of Area

C showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.64 Block plan of Area C

showing excavation units and section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.63 Detailed plan of Area

C showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.64 Block plan of Area C

showing excavation units and section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.38 Aerial view of Area

F after excavation from Leibner et al. (2018)

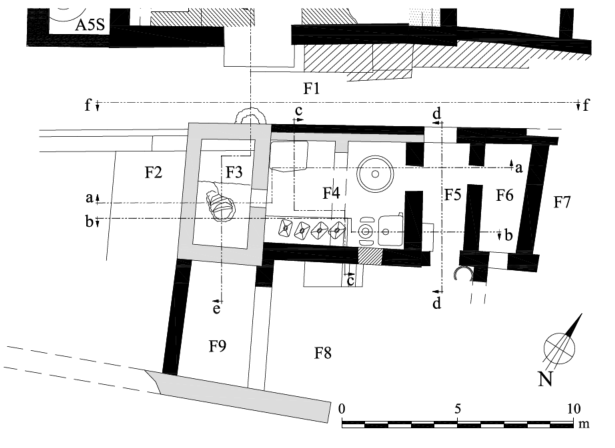

- Fig. 6.39 Block plan of Area

F showing excavation units and major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.40 Detailed plan of

Area F showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.38 Aerial view of Area

F after excavation from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.39 Block plan of Area

F showing excavation units and major section lines from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 6.40 Detailed plan of

Area F showing wall numbers and major locus numbers from Leibner et al. (2018)

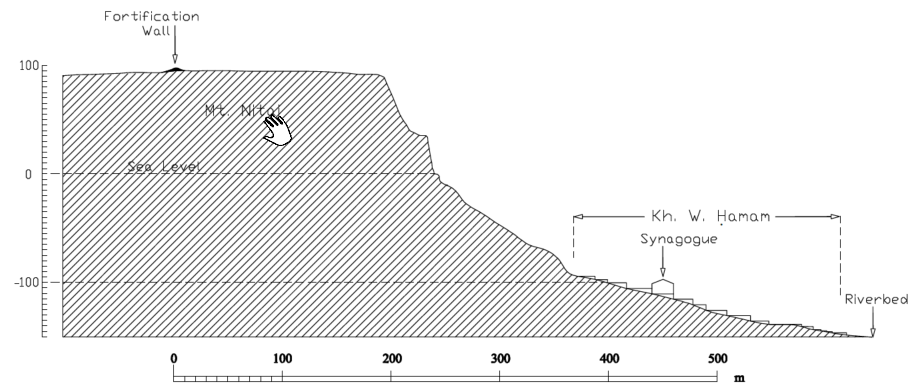

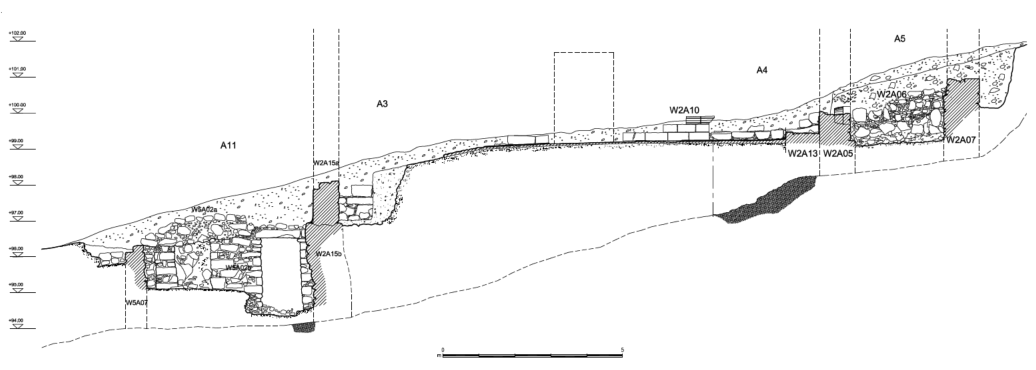

- Fig. 1.9 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.3 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.14 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.9 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.3 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.14 east–west section through

Mt. Nitai showing the topographical incline from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.10 Proposed reconstruction

of Kh. Wadi Ḥamam in the Late Roman period from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.11 Proposed reconstruction

of Kh. Wadi Ḥamam in the Late Roman period from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.10 Proposed reconstruction

of Kh. Wadi Ḥamam in the Late Roman period from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1.11 Proposed reconstruction

of Kh. Wadi Ḥamam in the Late Roman period from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.50 Through-going fracture

in Column Pedestal in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.51 coin embedded in the

plaster floor in the western aisle in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.53 collapsed wall of

synagogue in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.50 Through-going fracture

in Column Pedestal in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.51 coin embedded in the

plaster floor in the western aisle in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2.53 collapsed wall of

synagogue in Area A from Leibner et al. (2018)

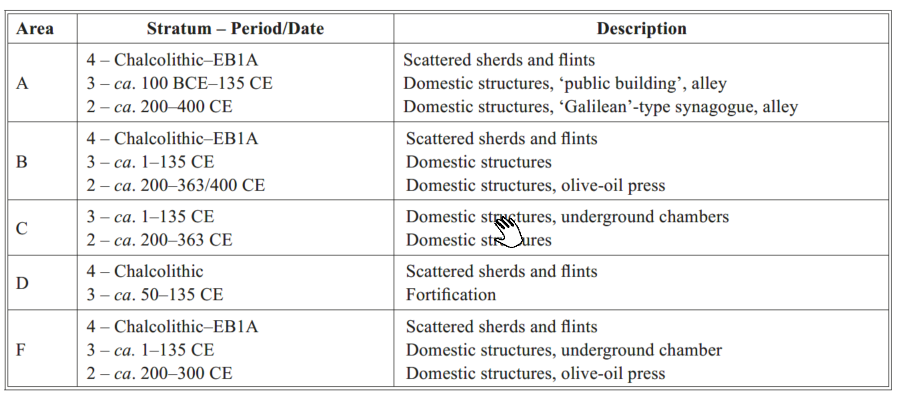

| Stratum | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Late Chalcolithic / Early Bronze Age IA | ca. 4500–3300 BCE | “The earliest remains, dated to the Late Chalcolithic period and Early Bronze Age IA, were entitled Stratum 4. Most of the finds from these periods were retrieved near bedrock and in fills beneath structures of Stratum 3 in Areas A and F. They comprise hundreds of pottery sherds and flints, a few groundstone implements and a zoomorphic clay figurine. No architectural remains could be assigned with certainty to this stratum, although the abundant small finds attest to extensive activities at the site during this era.” |

| 3 | Late Hellenistic / Early Roman | ca. 100 BCE–135 CE | “After a gap of some three millennia, the site was resettled during the Late Hellenistic (Hasmonean) period. Only a few architectural remains, found in Area A, could be assigned to this early stage. However, the considerable quantity of Late Hellenistic pottery recovered in fills beneath Early Roman structures, along with a dozen Seleucid and autonomous Phoenician coins from late second-century BCE Akko-Ptolemais and Tyre and some 90 Hasmonean coins, indicate that the occupation of Kh. Wadi Hamam began around the early first century BCE… The settlement expanded and developed during the Early Roman period, reaching its peak in terms of size and prosperity… Of special importance are the remains of a lavish ‘public building’, probably a Second-Temple period synagogue constructed in the center of the village around the mid-first century CE… The affluent occupation of Stratum 3 came to an abrupt end in a massive destruction documented in all excavation areas… to the reign of Hadrian, ca. 125–135 CE.” |

| 2 | Roman / Late Roman | ca. 200–400 CE |

"Following the second-century destruction, the site was

apparently abandoned for several decades, or at least

suffered a serious decline, as is evident from the

decrease in the quantities of coins dating to the latter

part of that century. A wide range of evidence for

habitation alongside the massive construction of new

structures appears around the end of the second or

early third century CE, designated Stratum 2. Remains

of this stratum were uncovered in all four excavation

areas in the village, indicating that Kh. Wadi Hamam

flourished again in the third and early fourth centuries

CE (Figs. 1.10–1.11). Reconstruction of the village was

based mostly along the lines of the early terraces,

although the plans of the domestic structures and the

general layout of the village differed from that of the

previous period. A ‘Galilean’-type synagogue was built

in the center of the village, where the earlier ‘public

building’ and dense domestic structures once stood. Evidence of a gradual decline of the settlement began to appear in the early fourth century, with the abandonment of a few structures. Many other structures were abandoned around the mid-fourth century, most likely as a result of the 363 CE earthquake. Activity in the second half of the fourth century was documented only in a restricted area in the center of the site, and village life seems to have ceased entirely by the end of the fourth or early years of the fifth century CE.” |

| 1 | Byzantine–Modern (ephemeral) | ca. 400–1950 CE | “Isolated small finds from the Byzantine, Umayyad, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman periods, up to the present day, were all grouped as Stratum 1. They were recovered in the topsoil with no relation to architectural remains and attest to ephemeral activities at the site, most likely pasturing and stone-robbery, or squatters making use of the ruins.” |

Despite its size, central location, and proximity to long-settled sites such as Magdala (2 km) and Tiberias (6 km), the ancient name of the site has long disappeared. The Arabic name Hamam (pigeon) derives from the flocks of pigeons nesting in the nearby cliffs, and was already recorded as the name of an agricultural plot in the Ottoman census of the sixteenth century— Mazraʿat Mugr al Hamam (Arabic “the sown land of the caves of Hamam”).7 In the British Survey of Western Palestine in the late nineteenth century, the site name was recorded as Kh. el-Wereidat (Arabic “the ruin of the small roses”).8 This peculiar name, alongside the better-known name Kh. Wadi el-Hamam, is also recorded in the first half of the twentieth century by the British Mandate Department of Antiquities and is the source of the current Hebrew name Horvat Veradim (Hebrew “ruin of the roses”).9 However, today the local Bedouin use the name el-Wereidat for a nearby burial site located 0.8 km to the north, also known as Waʿara el-Soda (see Chapter 20). Bedouin families who had settled in huts in the lower part of the site in the mid-twentieth century have since moved to the modern village of Wadi Hamam, to the east of the site (Fig. 1.5).

Based on the history of the ancient village as documented in our excavations, together with references in literary sources, the possibility arises of identifying Kh. Wadi Hamam with an ancient site called Migdal Zabaʿayya (K = “run,” Aramaic “Tower of the Dyers”).10 This site is mentioned several times in Palestinian rabbinic literature of the Amoraic period (third–fourth centuries CE) as an example of a prosperous settlement. It is clear from these sources that the site is located somewhere near Tiberias.11 Composite toponyms which include the prefix “Migdal” are common in ancient Aramaic and Hebrew and are usually followed by an attribute that aids in distinguishing them from other “towers,” for example: Migdal Gad, Migdal Gader, Migdal Malba and Migdal ʿEder. The town of Migdal Nunayya (Aramaic “Tower of the Fish”), also known by its comparable Greek name Tarichea (“Factories for Salting Fish”), is commonly identified with the nearby site of el-Mejdel. This town, located on the main road along the shore of the Sea of Galilee, is usually referred to in rabbinic literature simply as Magdala (i.e., “The Tower”) without its attribute, probably because of its fame and as it was well known to the rabbis who composed this literature.12 A major problem with references in rabbinic sources to Migdal Zabaʿayya and Magdala (i.e., Migdal Nunayya), is the confusion between them in parallel texts. Consequently, some scholars suggest that both names refer to the same settlement.13 However, it is difficult to accept the idea that one settlement had two different Aramaic names, and this in addition to a Greek name. It seems more likely that the Aramaic names refer to two different settlements, and in later periods transcribers who were unfamiliar with the peculiar name Migdal Zabaʿayya, changed it to the familiar and simpler name Magdala. If indeed this is the case, it implies that the texts in which the lectio difficilior name Migdal Zabaʿayya appears preserve the genuine version of the tradition.

In Genesis Rabbah 79 (pp. 941–945), following the famous story of the purification of Tiberias by R. Shimon bar Yobai, it says:

...He then departed to spend the Sabbath at home. Passing that Migdal Zaba` ayya14 he heard the voice of Nakai the Scribe saying: "have you not said that ben Yobai has purified Tiberias? Yet it is said that a corpse has been found there!" He (R. Shimon) said: "I swear that I know of innumerable (lit. as the hair on my head) laws attesting to the purity of Tiberias, except for certain places. (Besides) did you not vote (with those who declared Tiberias clean)? You have breached the fence of sages, `He who breaches a fence will be bitten by a snake' (Eccles. 10:8). Immediately one (a snake) emerged, and thus it had happened to him. He (R. Shimon) then passed through the valley of Beth Tofa.15 He saw a man standing and gathering the after-growth of the Sabbatical year. He said: "Is this not the after-growth of the Sabbatical year (and thus forbidden)?" He (the man) said: "Are you not the one who permitted it?" He (R. Shimon) said: "But do my colleagues not disagree with me?" Immediately he raised his eyebrows and looked at him, and (the man) became a heap of bones.16The most reasonable route of the (legendary?) journey of R. Shimon bar Yobai leads from Tiberias northward and then turns westward in Nabal Arbel, passing immediately below Kh. Wadi Hamam, and ascending directly to the Beth Netofa Valley. Migdal Zabaʿayya should be located somewhere along this route. The only substantial Roman-period sites along this course are el-Mejdel, Kh. Wadi Hamam and Kh. Umm el-`Amed (`Ammudim). As the first is clearly identified with Migdal Nunayya/Magdala/Tarichea, Migdal Zabaʿayya should probably be identified with one of the remaining two, whose ancient names are not preserved.

A tradition in Yerushalmi Ta `anit (1.6 [64c]) provides additional clues to the location of Migdal Zabaʿayya:

R. Hinena said: "All matters are a matter of custom". There were acacia trees in Migdal Zaba'ayya. They came and asked R. Hanina, associate of the rabbis, whether they might work with them (i.e., make use of them). He said to them: "since your forefathers have been accustomed to treat them as forbidden, do not change the custom of your forefathers, may they rest in peace".17In a similar story appearing in Song of Songs Rabbah (1.12 [55] Dunesky ed., p. 44), the reasoning for this refrainment is a tradition according to which the Children of Israel took from these trees when they went down to Egypt, and later built the holy ark from them. In any case, the only kind of acacia in northern Israel is the Acacia albida, which grows in small clusters in low, hot localities between the vicinity of Beth Shean and the Sea of Galilee basin.18 These conditions suit el-Mejdel and Kh. Wadi Hamam, but not Kh. Umm el-`Amed that is located ca. 300 m higher in elevation. Another hint as to the area in which the story takes place is the appeal of the locals of Migdal Zaba'ayya to `Rabbi Hanina associate of the rabbis', a relatively unknown sage who was active in Tiberias in the late third century CE.19

Most important for our discussion is the following tradition in Yerushalmi Ta `anit 4.5 [69a]), which elaborates on the statement in the Mishnah "five (disastrous) events befell our ancestors on the Ninth of Av... the First and Second temples were destroyed and Betar was captured":

The kitmos20 of three villages would be brought up to Jerusalem in a wagon (i.e., due to its abundance): Kabul, Shikhin and Migdal Zaba'ayya, and all three were destroyed. Kabul because of contention; Shikhin because of witchcraft; and Migdal Zaba'ayya because of fornication... R. Yohanan said: there were eighty stores of palgas21 weavers in Migdal Zaba'ayya ...22Kabul and Shikhin (Asochis) are well known from both Josephus and rabbinic sources and their identification is clear: the first is located in the western Lower Galilee, near `Akko, and the second in the central Lower Galilee, near Sepphoris.23 Nearly a century ago, Press identified Migdal Zaba'ayya with el-Mejdel and suggested that this tradition is organized geographically from west to east, hence covering the entire Lower Galilee.24 This suggestion seems convincing, although as noted, el-Mejdel should clearly be identified with Migdal Nunayya/Magdala, hence Migdal Zaba'ayya is to be sought elsewhere in the eastern Lower Galilee. It would be helpful, of course, if we knew to what destruction the tradition alludes. The report by Josephus on the burning of Kabul by the Romans during the First Jewish Revolt,25 led Klein to attribute these destructions to that revolt.26 However, it is unclear if the rabbinic tradition is referring to a single event that brought about the devastation of all three villages. Furthermore, the literary context of the tradition seems actually to point to events connected to the Bar Kokhba Revolt rather than the First Jewish Revolt. It appears in a section that begins with a quo-tation from the Mishnah "Betar was captured", immediately after the dreadful legends about the siege and fall of Betar, and it is integrated in a series of stories about the wealth of various settlements, such as Tur Shim'on and Har ha-Melekh, which in all likelihood were destroyed during the Bar Kokhba Revolt.27

The excavations at Kh. Wadi Hamam revealed that the affluent settlement of Stratum 3 came to an abrupt end in a massive destruction, dated on the basis of coin hoards to the reign of Hadrian, ca. 125-135 CE (see Chapters 2, 6, 15), a date that raises the possibility that the destruction was connected to the events of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. To date, this is the only site in the Galilee where finds may point to a local participation in that revolt. It should also be noted that rabbinic sources refer to Kabul, Shikhin and Migdal Zaba'ayya as Jewish villages existing also after the revolts.28 This, too, fits the evidence from Kh. Wadi Hamam, which flourished again a few generations after the destruction.

The tradition of many stores of weavers existing in the village corresponds with the name Tower of Dyers, implying textile production.29 Alternatively, this tradition may have developed precisely because of the peculiar ancient name. Rabbinic sources mention textile production also at Arbel, on the southern bank of the wadi.30 To date, no archaeological evi-dence for textile production has been found at Kh. Wadi Hamam.

Of the remaining sources that mention Migdal Zaba'ayya,31 only one contains geographical information that may assist in locating the site. A midrash in Leviticus Rabbah 17.4 (ed. Margulies, p. 378) describes the journey of the servants of Job on their way to tell him of the disasters that fell upon his descendants and property:

[a messenger came to Job and said...] the Sabeans made a raid and took them (the cattle) [and have slain the servants]' (Job 1.15). R. Abba bar Kahana said: They went from Kefar Kernos, and through all the Aulon and reached Migdal Zaba'ayya and died there. `And only I escaped to tell you' (ibid.): R. Yudan said: Wherever (in scripture) it is said `only', it implies a restriction. He (the messenger) too, was broken and stricken. R. Yudan said... and he too, as soon as he told his message, immediately died... `While he was still speaking, another messenger came and said: The Chaldeans formed three raiding parties [and swept down on your camels and made off with them] (Job 1.17). R. Samuel b. Nahman said: As soon as Job heard this he began marshalling his warriors... (but) when he was told `A fire of God is fallen from heaven' (Job 1.16) he said: What can I do. A voice has fallen from heaven! Who can do anything? ...32What is the meaning of this ambiguous midrash? And why does it elaborate on a journey of Jobs' servants through sites that are not mentioned either in the story or in the Bible in general? It seems that the rabbis are alluding to events in these places that were known to their contemporaneous audience but whose meaning is hidden from us today.33 In any case, two of the places mentioned here can be clearly identified: Kefar Kernos is mentioned in the Talmud Yerushalmi and in the halachic inscription from the Rebov synagogue, both pointing to a village adjacent to Beth Shean.34 Aulon is mentioned in the Septuagint (Deut. 1.1, Hebrew Hazeroth) and is identified in the Onomasticon of Eusebius as follows:

The great long plain is still called the Aulon (Aviv). It is bordered on both sides by mountains extending from Lebanon to the desert of Pharan. In the Aulon is the famous city [Tiberias] and nearby the lake, Scythopolis, Jericho and the Dead Sea and their surrounding regions. The Jordan flows through the midst of the whole region....35Thus, the Aulon is what is called today the Jordan Valley. According to the story, Job's servants began their journey near Beth Shean, passed through the Jordan Valley and all but one died at Migdal Zaba'ayya, again indicating that this village is located somewhere in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee. In this context, it should be noted that a tradition appearing in the Babylonian Talmud, and in some manuscripts of Genesis Rabbah, states that Job lived in Tiberias.36 This may be the reason for the development of our story focusing on sites in this region. It is not clear why Migdal Zaba'ayya was chosen as the servants' death-place. The tradition, brought by R. Abba bar Kahana who lived in the Galilee in the late third—early fourth centuries CE, may allude to a known tragedy that occurred in that village, such as the early second-century destruction mentioned above or perhaps an earthquake (the `fire of God fallen from heaven' at the end of the story?). The excavations at Kh. Wadi Hamam revealed evidence of two destructive episodes that seem to be the result of earthquakes, the first in the late third or early years of the fourth century CE, and the second in the year 363 CE (see Chapters 2, 6).

In conclusion, Migdal Zaba'ayya should be situated somewhere near the Sea of Galilee, apparently not too far from Tiberias. The clues in the literary sources as to its location and events that took place there, are consistent with the location of Kh. Wadi Hamam and its history, as revealed in our excavations. At this stage in the research, however, this identification must remain a plausible suggestion.

7 Rhode 1979: 88.

8 Conder and Kitchener 1881: 409.

9 British Mandate Department of Antiquities Archive,

SRF 192 (7/7) and Jacket ATQ 1045 (3/3).

10 This suggestion was first raised in my Ph.D.

dissertation (Leibner 2004: 218–226), but later I

proposed identifying Migdal Zabaʿayya with a

different site, south of Tiberias (Leibner 2006).

The excavation results, however, have led me to

return to my initial suggestion.

11 Various identifications have been suggested by

scholars for this site, all in the vicinity of the Sea

of Galilee, see, e.g., Schwarz 1979: 228; Graetz

1880; Press 1930: 255–268; 1961: 162–170; Klein

1967: 199–201; Feliks 1981: 22. The suggestion of

Taylor (2014: 209–210) that the site be sought in

the vicinity of Jerusalem does not stand up to

scrutiny.

12 For a detailed discussion on the identification of

Migdal Nunayya/Magdala/Tarichea and the

etymology of the names, see de Luca and Lena

2015: 280–298, with references therein.

13 Neubauer 1868: 217; Press 1930; 1961: 164;

de Luca and Lena 2015: 289.

14 In the parallels (Yerushalmi Sheviʿit 9.1 [38d];

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 11.16 [ed. Mandelbaum,

p. 193]; Kohelet Rabbah 10.8), the reading is

Magdala.

15 In some mss.: Beth Netofa / Beth Tifa.

16 Translation (with modifications) after Levine

1978, who provides a detailed comparison

between the parallel traditions and an extensive

discussion of the story.

17 A parallel with small variations appears in

Yerushalmi Pesahim 4.1 [30d].

18 Feliks 1981: 22.

19 See Yerushalmi Berakhot 7.3 [11b]; Moʿed Katan

3.5 [82c]; Terumot 8.3 [45c]; see also Beer 1983:

80–82; Rosenfeld 1998: 57–103.

20 Apparently from [Greek text], here meaning

revenue or donations.

21 Palgas, perhaps from [Greek text] — a cloak, see

Sperber 1993: 132–140.

22 A similar tradition, which apparently developed

from this source, appears in Lamentations Rabbah

2.2 (Buber edition p. 54): R. Huna said: There were

three hundred stores selling [food preserved in

the condition of] cultic cleanness in Migdal

Zabaʿayya …

23 Tsafrir et al. 1994: 102; Strange et al. 1995.

24 Press 1930; 1961: 164.

25 War 2.505.

26 Klein 1967: 50.

27 For Tur Shimʿon and Har ha-Melekh, see Zissu

2008 and Shahar 2000, respectively.

28 See the relevant entries in Tsafrir et al. 1994:

102, 70, 173.

29 The ancient Jewish text dubbed Toledot Yeshu

presents a derogatory version of the life of

Jesus. Interestingly, in the Aramaic version of

the text, presumably originating in the

Byzantine period, in a scene set in the

vicinity of Tiberias, John the Baptist is

called limn= pni, (Deutsch 2000: 186, Lines 4,

9, 15). This nickname is usually translated as

John the Dyer and is thought to be an

unarticulated use of the verb vn2 (Zab`a),

which means to dye but also to dip/immerse,

hence to baptize (idem.: 179). However, the

prefix h is usually used to designate the

place of origin, and could be understood as

John from Zaba'ana.

30 Genesis Rabbah 19.1 (ed. Theodor-Albeck

p. 170); see also Ilan and Izdarechet

(1988: 36), who suggest that pools identi-

fied at Arbel were used in flax processing.

31 For example, Yerushalmi Ma'aser Sheni 5.2

(56a); Kohelet Rabbah 1.8 (Hirshman ed.

p. 64).

32 Translation (with modifications) after

Freedman and Simon 1939: 217-218.

33 For a detailed discussion of this midrash,

see Leibner 2006: 41-49.

34 Yerushalmi Demai 2.1 [22c]; Sussmann

1973-74: 158; see also Leviticus Rabbah

28.6 (ed. Margulies p. 666); Yahalom and

Sokoloff 1999: 208-210.

35 Onomasticon, ed. Klostermann, p. 14.

Interestingly, in the Latin translation

(idem.: 15) Jerome emphasizes that Aulon

is not Greek, as one might think, but rather

a Hebrew word.

36 Bavli Bava Batra 15a; Genesis Rabbah 57.4

(ed. Theodor and Albeck, p. 617) according

to mss. Oxford 147, Oxford 2335, Paris 149.

The current section presents a stratigraphic synthesis focusing on the main terrace and the monumental buildings that stood on it, based on the details and archaeological finds discussed above

Limited restoration works in Synagogue II at the end of the fourth century were labeled Sub-Phase IIb, and include the addition of three stratigraphically related features: (1) a stone bema; (2) a low bench added against the southern wall; (3) a plaster floor, which replaced damaged portions of the mosaic. The cause and date of the damage that necessitated this renovation could not be precisely determined, but it clearly occurred in the late fourth century. The most plausible event is the earthquake of 363 CE, which was apparently responsible for the destruction of some of the surrounding domestic structures and devastated many sites in the region (see Chapter 6).19

No traces of a bema attributable to Synagogue I or II were detected, although we must admit that the southern part of the synagogue is poorly preserved. The fact that the bema of Sub-Phase IIb was built directly upon the mosaic floor certainly indicates that no stone-built bema stood here in Phase II. Remains of the mosaic found in the southeastern part of the nave similarly preclude the option that a bema stood on the other side of the main entrance in Phase II. In other synagogues in the region, such as Hammat Tiberias, a stone-built bema was also added in the fourth century where previously none had existed.20

The bema and the low bench added in Sub-Phase IIb are constructed of reused architectural elements and are poorly and sloppily executed, reflecting the decline of the synagogue. Similarly, the replacement of large portions of the mosaic with a plaster floor attests that at the time of the renovation, the community lacked the means to repair or replace the mosaic. It is noteworthy that despite the heavy damage, the surviving mosaic segments were preserved and not plastered over, evidence that they were considered sufficiently important to be preserved as much as possible (no other such instance of the ancient preservation of a synagogue mosaic is known to date). This situation is consistent with the general picture revealed in the excavations that by the late fourth century, most of the village was already deserted

19 For archaeological evidence of the earthquake of

363, see Russell 1980; Balouka 1999

20 Dothan 1983: 31–32;ugeneral, Weiss

1988.

The debris in the northwestern quarter of the synagogue hall, which had accumulated to a maximal height of ca. 2.2 m above floor level, provided important information concerning the last stage of the building and its final collapse. The components of the corner column had fallen to the southwest, and courses of blocks from the walls, still bound together by mortar, were discovered lying on their sides among the debris. In the debris were hundreds of roof tiles and dozens of large construction nails that probably originated from the truss that supported the tiled roof. All this evidence seems to imply that the final collapse was caused by an earthquake. The latest pottery and small finds on the floor beneath the debris date to the fourth–early fifth centuries. These finds were probably washed in from above after the abandonment of the building, but before its collapse, and seem to have been sealed inside shortly thereafter, since no material of later date was recovered on the floor. Thus, the building probably collapsed in an earthquake in the early years of the fifth century (perhaps in 419?).21 The similarity between the material beneath the debris and that found inside the bema indicates that the renovations in Sub-Phase IIb took place shortly before the destruction of the building. As noted above, the two successive plaster floors in some places suggest two stages of renovation in this sub-phase.

21 The earthquake of 419 is mentioned in the Chronicon Marcellini (Mommsen 1894: 74); see also Russell 1985: 42–43; Amiran, Arieh and Turcotte 1994: 266.

A few finds provide evidence of limited activity that took place in and around the synagogue after its collapse. The nature of the finds, the small quantity and their location, indicate that these were sporadic activities reflecting stone robbers, squatters, or passersby who visited the site.

On the alley surface to the north of the synagogue, a pottery assemblage of the late fourth–early fifth centuries was recovered, and some of the vessels were restorable. As the domestic structures to the north had apparently collapsed in the earthquake of 363 CE, this strange location for pottery vessels suggests squatters making use of the alley after the surrounding structures, and perhaps also the synagogue, had gone out of use. A number of Umayyad-period oil lamps, as well as a Mamlukian painted jar, were found beneath the collapsed vault in Room A6, evidence that this room survived long after the village and its synagogue were abandoned. In the corridor on the upper terrace to the west (Unit A9), two consecutive tabuns were built against the outer face of the synagogue’s wall on a layer of collapsed stones. This odd location, and the fact that the tabuns were constructed of tiles originating from the synagogue roof, demonstrate that they were built after the synagogue went out of use. Two sixth-century coins found nearby suggest a Late Byzantine date for this activity.

An eighth-century coin from the debris of the eastern wall may point to stone robbery during the Umayyad period (L.5A007; Cat. No. 373). Similarly, a 1949 coin found immediately above the floor in the southern part of the nave, and a few audio cassettes recovered nearby, attest to activity and perhaps stone robbing in the twentieth century as well.

The plan and function of this area in Stratum 3 is unknown as only two of the walls here can be attributed to that period (W3B02, W3B03), and in both cases, it appears that our excavation only exposed their exterior faces. The abundant Early Roman finds, however, point to some activity here or in the immediate vicinity in that period. The complex as described above clearly belongs to Stratum 2 (Fig. 6.14), and the coherent plan and homogenous finds seem to indicate that all the units were built and functioned contemporaneously. Furthermore, as no changes or restorations were discerned, the entire complex apparently had only one phase. The entrances to the dwellings on both sides of the courtyard had lockable doors, suggesting that distinct families lived on either side of a shared courtyard. As the southern wall of the courtyard was not exposed, we may speculate on the existence of an additional structure that opened onto this courtyard.

While a precise date for the construction of this complex could not be determined, the few finds in loci beneath the floors (e.g., L.5B018 in Unit B2) suggest sometime within the course of the third century. The latest finds in all the units indicate that the entire complex was abandoned around the mid-fourth century CE. The latest coin dates to 351–361 CE (Cat. No. 301), hinting of a connection with the earthquake of 363 CE. However, as no restorable pottery or implements were recovered, it seems that the structure was deserted in an organized manner, and not as a result of a sudden catastrophe.

The area south of the oil press was excavated in the 2007 and 2008 seasons, starting with a 5.5 × 5 m square to the south of W1B04 and east of W1B01 (Units B7–B8), followed by an adjacent 4 × 4 m trench to the southwest, on both sides of W2B02 (Unit B10; Figs. 6.2, 6.29). As in Units B5–B6, excavation here revealed a Stratum 2 structure built on a huge fill that totally buried a Stratum 3 house up to the top of the first floor. The area consists of a dense series of walls belonging to both strata (see Fig. 6.1). Due to space limitations and safety constraints, the excavation reached the floor level of the Stratum 3 structure only in Unit B7. In general, the walls of the Stratum 3 structure are similar in building technique to the other structures of this stratum: they are founded on the talus slope and built of two faces of large fieldstones or partially dressed stones, of both basalt and hard limestone, with small stones in between them. The walls of Stratum 2, on the other hand, are built mainly of small stones and ‘float’ on the debris with almost no foundation courses beneath floor level.

In Stratum 2, Unit B7 consists of a rectangular room (4.6 × 3 m, inner dimensions) bordered on the north by W1B04, on the east by W2B06, on the south by W2B01 and on the west by W1B01. The northern and eastern walls are bonded in the northeastern corner and abut the southern and western walls that are bonded in the southwestern corner. The walls are preserved to a height above floor level of ca. 1.3 m in the west and 0.5 m in the east. Although it is evident that the builders were familiar with the subjacent Stratum 3 walls, they did not construct their walls on top of them, but rather on top of the debris. A seam is clearly seen in W1B01, and to the south of it the wall is built on the debris (Fig. 6.30), suggesting that the southern part of this wall is a Stratum 2 addition (see below).

Following removal of the dark topsoil (L.1B009), a collapse of building stones appeared (L.1B012, L.2B004, L.2B008, L.2B011). While dismantling the collapse, the tops of W2B05 and W2B07, which were buried within it, were revealed. No clear floor of the upper structure survived, but it seems to have been at a similar elevation as the floor of the adjacent Unit B6 (ca. 100.20 m asl). The pottery from the collapse in the above-mentioned loci resembles that found in the oil press in Unit B6 and includes mainly fourth-century pottery (see Chapter 9: Pl. 9.21:1–7).

In Stratum 3, Unit B7 is bordered by W2B05 in the north and W2B07 in the east, which bond at the corner. The outer corner is abutted from the north by what might be the continuation of W1B05. The eastern wall (W2B07) curves slightly towards the east, perhaps a result of an earthquake or pressure caused by collapsed debris. The northern wall runs below W1B01 to the west, and the closing wall of the lower structure must be further to the west. The room is closed on the south by W2B08, exposed in the adjacent square, hence the inner width of the room is 4 m.

Excavation into the lower, Stratum 3 structure revealed what seems to be a massive intentional fill of light brown soil with many small to large stones (L.2B013, L.2B019, L.2B020, L.2B022). The finds in the fill comprised mainly Stratum 3 pottery, including two restorable KH4b/c cooking pots (at ca. 99.30 m asl), similar to those found in the ash layer in the adjacent units (see Chapter 9: Pl. 9.21:8–9). Also found in the fill were an intact upper part of an Olynthus millstone (see Chapter 12: Pl. 12.1:4), and a coin of Herod the Great (see Chapter 15: Cat. No. 105). The excavation reached beneath the foundation courses of W2B05 and W2B07 only in the eastern half of the room (L.2B024; Fig. 6.31). No floor was discerned here, nor was there an ash layer or any signs of intentional destruction. Remarkably, the foundation courses of these walls are higher in elevation than the floors of Units B5 and B6, hence the floor here must have been higher. The meager finds in this lowest locus include Bronze Age, Hellenistic and Early Roman pottery, suggesting a first-century CE date for the construction.

In summary, the Stratum 3 structure in Unit B7 is a 4-m-wide room (the length is unknown), built in the same technique, in the same orientation, and apparently in the same period, as the ‘burnt house’ to the north. Its eastern wall (W2B07) is aligned with that of Unit B6 (W1B05), suggesting that the two rooms may belong to one large domestic complex. However, the western wall was evidently not aligned with that of Unit B6 and the floor elevation must have been higher. We do not know if the structure had a second story and the entrance was not revealed. Based on the orientation of the terrace and parallels from the site, the structure was most likely entered from the east. Like the adjacent units, this room was intentionally filled up and leveled to the top of the first story, and a Stratum 2 structure was built on top.

Unit B8 in Stratum 2 is a 3-m-wide room, bordered on the north by W1B04, on the west by W2B06 and on the south by W2B01. It was only partially excavated and its eastern wall was not revealed. It is aligned with Unit B7 to the west and they share all the above-mentioned walls. It also shares W1B04 with the oil press to the north, hence all these units seem to belong to one large complex. We may speculate that its eastern wall was in alignment with W5B01/W3B02 unearthed in the units to the north, suggesting a 4-m-long room.

Excavation in Unit B8 comprised a single locus (L.2B025) of brown topsoil and below it a collapse of small to large stones. No floor was identified and it seems that the excavation here began beneath floor level. Excavation ceased at 99.00 m asl, after reaching beneath the foundation courses of all three surrounding walls (Fig. 6.32). The finds from the collapse included fourth-century pottery similar to that from Unit B7 and the oil press (see Chapter 9: Pl. 9.21:10–15), as well as an Early Roman glass bottle (see Chapter 13: Pl. 13.3:21).

Unit B10 was excavated as a 4 × 4 m square southeast of Unit B7, south of W2B01 and on both sides of W2B02 (Fig. 6.29). After removing the topsoil and revealing the top of the walls, a narrow trench was excavated west of W2B02 in order to clarify architectural questions (L.2B006, L.2B031). This revealed a collapse of building stones and indicated that W2B02 abuts W1B01 to the north, while in the south it bonds with the corner of W2B03, which runs to the west. The latter wall was exposed partially here and partially in Unit B11, further to the west (W5B04, see below). It also revealed that W2B01 does not continue further west. In this trench, L.2B031 yielded fourth-century pottery, two Late Roman glass bowls (see Chapter 13: Pl. 13.4:31, 33) and a blade of an iron knife (see Chapter 14: Pl. 14.1:11).

In the eastern half of the square was a massive collapse of building stones (L.2B007, L.2B026), which was partially removed, exposing the top of W2B08. Excavation in the narrow space between W2B08 and W2B01 (L.2B030) revealed that the latter ‘floats’ on top of the collapse, while the former continued much further down and belongs to the lower structure of Stratum 3. This is apparently the southern wall of the room described above in Unit B7. South of W2B08, excavation continued as L.2B029, revealing what seemed to be a fill of large stones and light brown soil. At the base of the western wall (W2B02) was a projecting course, apparently its foundation (Fig. 6.33). Excavation ceased on both sides of W2B08 at ca. 99.10 m asl, without descending to the lower structure.

No clear floor of the upper structure was detected. The finds in the collapse seem to be a mixture of Stratum 2 pottery, including fourth–early fifth-centuries pottery (see Pl. 9.21:16–28), together with an Early Roman glass bowl (see Chapter 13: Pl. 13.1:8), two knife-pared and one bilanceolate oil lamp (see Chapter 11: Pl. 11.1:4), a modern coin and a coin of Antiochus III (223–187 BCE; see Chapter 15: Cat. No. 2).

... In summary, although the plan of this area in Stratum 3 is unclear, the northern wall and the blocked underground chamber seem to date back to that period. Unit C 1, as it has survived, clearly belongs to Stratum 2. Based on the width of this unit, which would be difficult to roof, and on the storage installations along the northern wall, it was probably an inner courtyard fronting the dwelling to the west. The huge collapse that buried this unit hints of destruction caused by an earthquake, most likely that of 363 CE. The chronologically homogenous finds above the floor seem to indicate that the structure remained untouched until our excavation.

The plan and function of the structure on the upper terrace of Area C in Stratum 3 is unclear, although the wall bordering the area on the north (W3C07) and the subterranean chambers seem to date back to that period. These chambers, connected underground, were only partially excavated and their purpose could not be clarified (see further below).

The builders of the Stratum 2 complex leveled the earlier structure on the lower terrace and reused some of its walls for their new construction. The coherent plan, the shared courtyard and walls, the similar construction date and the fact that no doors were installed in any of the openings facing the courtyard, all seem to indicate this was a privately-owned complex, perhaps of an extended family (Fig. 6.75). There was no unequivocal evidence of a second story, and apart from a blockage in the southern courtyard opening, no restorations or alterations during its existence were identified in any part of the complex.

The upper complex was apparently constructed slightly after the mid-third century and was in use for about a century, until it was abruptly abandoned. Although some of the pottery vessels recovered from the complex are types that continue to appear in fifth-century contexts, the assemblage as a whole clearly dates to the decades around the mid-fourth century, with no datable material that must be later. In addition to the pottery vessels, the latest finds in Area C as a whole include a dozen coins from the House of Constantine, the latest of which are issues of Constantius II (337–361 CE; Table 6.1). This is in sharp contrast to the finds in Area A and the oil press in Area B, where many late fourth-century minimi coins were recovered, as well as ceramic fine-ware imports of the late fourth–early fifth centuries, such as Cypriot Red Slip Form 1 (see above). The combination of ceramic types and coins enables us to date the abandonment of the complex, and of Area C as a whole, to the decades around the mid-fourth century. The sudden cessation and the huge collapse under which it was buried suggests the 363 CE earthquake as the cause of this desertion, a date which is clearly manifested by the latest coins found in Area C.

The northern wing of this large insula was excavated almost in its entirety, with some information of other parts also revealed (Fig. 6.60). Little is known of the plan of this area in Stratum 3, as only the western room (Unit F3), and perhaps the northern wall of Unit F4, could be dated securely to that period. The insula as a whole, as presented here in Fig. 6.40, belongs to Stratum 2, and the finds from probes beneath the floors and against wall foundations in several locations point to a date in the early third century for its construction. The existence of an olive-oil press in the midst of what seems to be a domestic complex is surprising, and even more intriguing is its location opposite the synagogue in the center of the village.

The latest finds from the excavated part of this complex seem to point to a sudden abandonment, most likely due to a collapse. As the rich assemblages on the floors of the various units do not include any vessels that began to appear in mid-fourth-century assemblages, as were discovered in Area B to the north of the synagogue (Units B1, B2, B3, B4), it can be deduced that this insula was abandoned somewhat earlier than the 363 CE earthquake, perhaps in the 330s or 340s. If so, in its final phase in the second half of the fourth century, the synagogue was bordered on the north (Unit B11) and south by collapsed and abandoned structures.

Despite its size, central location, and proximity to long-settled sites such as Magdala (2 km) and Tiberias (6 km), the ancient name of the site has long disappeared. The Arabic name Hamam (pigeon) derives from the flocks of pigeons nesting in the nearby cliffs, and was already recorded as the name of an agricultural plot in the Ottoman census of the sixteenth century— Mazraʿat Mugr al Hamam (Arabic “the sown land of the caves of Hamam”).7 In the British Survey of Western Palestine in the late nineteenth century, the site name was recorded as Kh. el-Wereidat (Arabic “the ruin of the small roses”).8 This peculiar name, alongside the better-known name Kh. Wadi el-Hamam, is also recorded in the first half of the twentieth century by the British Mandate Department of Antiquities and is the source of the current Hebrew name Horvat Veradim (Hebrew “ruin of the roses”).9 However, today the local Bedouin use the name el-Wereidat for a nearby burial site located 0.8 km to the north, also known as Waʿara el-Soda (see Chapter 20). Bedouin families who had settled in huts in the lower part of the site in the mid-twentieth century have since moved to the modern village of Wadi Hamam, to the east of the site (Fig. 1.5).

Based on the history of the ancient village as documented in our excavations, together with references in literary sources, the possibility arises of identifying Kh. Wadi Hamam with an ancient site called Migdal Zabaʿayya (K = “run,” Aramaic “Tower of the Dyers”).10 This site is mentioned several times in Palestinian rabbinic literature of the Amoraic period (third–fourth centuries CE) as an example of a prosperous settlement. It is clear from these sources that the site is located somewhere near Tiberias.11 Composite toponyms which include the prefix “Migdal” are common in ancient Aramaic and Hebrew and are usually followed by an attribute that aids in distinguishing them from other “towers,” for example: Migdal Gad, Migdal Gader, Migdal Malba and Migdal ʿEder. The town of Migdal Nunayya (Aramaic “Tower of the Fish”), also known by its comparable Greek name Tarichea (“Factories for Salting Fish”), is commonly identified with the nearby site of el-Mejdel. This town, located on the main road along the shore of the Sea of Galilee, is usually referred to in rabbinic literature simply as Magdala (i.e., “The Tower”) without its attribute, probably because of its fame and as it was well known to the rabbis who composed this literature.12 A major problem with references in rabbinic sources to Migdal Zabaʿayya and Magdala (i.e., Migdal Nunayya), is the confusion between them in parallel texts. Consequently, some scholars suggest that both names refer to the same settlement.13 However, it is difficult to accept the idea that one settlement had two different Aramaic names, and this in addition to a Greek name. It seems more likely that the Aramaic names refer to two different settlements, and in later periods transcribers who were unfamiliar with the peculiar name Migdal Zabaʿayya, changed it to the familiar and simpler name Magdala. If indeed this is the case, it implies that the texts in which the lectio difficilior name Migdal Zabaʿayya appears preserve the genuine version of the tradition.

In Genesis Rabbah 79 (pp. 941–945), following the famous story of the purification of Tiberias by R. Shimon bar Yobai, it says:

...He then departed to spend the Sabbath at home. Passing that Migdal Zaba` ayya14 he heard the voice of Nakai the Scribe saying: "have you not said that ben Yobai has purified Tiberias? Yet it is said that a corpse has been found there!" He (R. Shimon) said: "I swear that I know of innumerable (lit. as the hair on my head) laws attesting to the purity of Tiberias, except for certain places. (Besides) did you not vote (with those who declared Tiberias clean)? You have breached the fence of sages, `He who breaches a fence will be bitten by a snake' (Eccles. 10:8). Immediately one (a snake) emerged, and thus it had happened to him. He (R. Shimon) then passed through the valley of Beth Tofa.15 He saw a man standing and gathering the after-growth of the Sabbatical year. He said: "Is this not the after-growth of the Sabbatical year (and thus forbidden)?" He (the man) said: "Are you not the one who permitted it?" He (R. Shimon) said: "But do my colleagues not disagree with me?" Immediately he raised his eyebrows and looked at him, and (the man) became a heap of bones.16The most reasonable route of the (legendary?) journey of R. Shimon bar Yobai leads from Tiberias northward and then turns westward in Nabal Arbel, passing immediately below Kh. Wadi Hamam, and ascending directly to the Beth Netofa Valley. Migdal Zabaʿayya should be located somewhere along this route. The only substantial Roman-period sites along this course are el-Mejdel, Kh. Wadi Hamam and Kh. Umm el-`Amed (`Ammudim). As the first is clearly identified with Migdal Nunayya/Magdala/Tarichea, Migdal Zabaʿayya should probably be identified with one of the remaining two, whose ancient names are not preserved.

A tradition in Yerushalmi Ta `anit (1.6 [64c]) provides additional clues to the location of Migdal Zabaʿayya:

R. Hinena said: "All matters are a matter of custom". There were acacia trees in Migdal Zaba'ayya. They came and asked R. Hanina, associate of the rabbis, whether they might work with them (i.e., make use of them). He said to them: "since your forefathers have been accustomed to treat them as forbidden, do not change the custom of your forefathers, may they rest in peace".17In a similar story appearing in Song of Songs Rabbah (1.12 [55] Dunesky ed., p. 44), the reasoning for this refrainment is a tradition according to which the Children of Israel took from these trees when they went down to Egypt, and later built the holy ark from them. In any case, the only kind of acacia in northern Israel is the Acacia albida, which grows in small clusters in low, hot localities between the vicinity of Beth Shean and the Sea of Galilee basin.18 These conditions suit el-Mejdel and Kh. Wadi Hamam, but not Kh. Umm el-`Amed that is located ca. 300 m higher in elevation. Another hint as to the area in which the story takes place is the appeal of the locals of Migdal Zaba'ayya to `Rabbi Hanina associate of the rabbis', a relatively unknown sage who was active in Tiberias in the late third century CE.19

Most important for our discussion is the following tradition in Yerushalmi Ta `anit 4.5 [69a]), which elaborates on the statement in the Mishnah "five (disastrous) events befell our ancestors on the Ninth of Av... the First and Second temples were destroyed and Betar was captured":

The kitmos20 of three villages would be brought up to Jerusalem in a wagon (i.e., due to its abundance): Kabul, Shikhin and Migdal Zaba'ayya, and all three were destroyed. Kabul because of contention; Shikhin because of witchcraft; and Migdal Zaba'ayya because of fornication... R. Yohanan said: there were eighty stores of palgas21 weavers in Migdal Zaba'ayya ...22Kabul and Shikhin (Asochis) are well known from both Josephus and rabbinic sources and their identification is clear: the first is located in the western Lower Galilee, near `Akko, and the second in the central Lower Galilee, near Sepphoris.23 Nearly a century ago, Press identified Migdal Zaba'ayya with el-Mejdel and suggested that this tradition is organized geographically from west to east, hence covering the entire Lower Galilee.24 This suggestion seems convincing, although as noted, el-Mejdel should clearly be identified with Migdal Nunayya/Magdala, hence Migdal Zaba'ayya is to be sought elsewhere in the eastern Lower Galilee. It would be helpful, of course, if we knew to what destruction the tradition alludes. The report by Josephus on the burning of Kabul by the Romans during the First Jewish Revolt,25 led Klein to attribute these destructions to that revolt.26 However, it is unclear if the rabbinic tradition is referring to a single event that brought about the devastation of all three villages. Furthermore, the literary context of the tradition seems actually to point to events connected to the Bar Kokhba Revolt rather than the First Jewish Revolt. It appears in a section that begins with a quo-tation from the Mishnah "Betar was captured", immediately after the dreadful legends about the siege and fall of Betar, and it is integrated in a series of stories about the wealth of various settlements, such as Tur Shim'on and Har ha-Melekh, which in all likelihood were destroyed during the Bar Kokhba Revolt.27

The excavations at Kh. Wadi Hamam revealed that the affluent settlement of Stratum 3 came to an abrupt end in a massive destruction, dated on the basis of coin hoards to the reign of Hadrian, ca. 125-135 CE (see Chapters 2, 6, 15), a date that raises the possibility that the destruction was connected to the events of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. To date, this is the only site in the Galilee where finds may point to a local participation in that revolt. It should also be noted that rabbinic sources refer to Kabul, Shikhin and Migdal Zaba'ayya as Jewish villages existing also after the revolts.28 This, too, fits the evidence from Kh. Wadi Hamam, which flourished again a few generations after the destruction.

The tradition of many stores of weavers existing in the village corresponds with the name Tower of Dyers, implying textile production.29 Alternatively, this tradition may have developed precisely because of the peculiar ancient name. Rabbinic sources mention textile production also at Arbel, on the southern bank of the wadi.30 To date, no archaeological evi-dence for textile production has been found at Kh. Wadi Hamam.

Of the remaining sources that mention Migdal Zaba'ayya,31 only one contains geographical information that may assist in locating the site. A midrash in Leviticus Rabbah 17.4 (ed. Margulies, p. 378) describes the journey of the servants of Job on their way to tell him of the disasters that fell upon his descendants and property:

[a messenger came to Job and said...] the Sabeans made a raid and took them (the cattle) [and have slain the servants]' (Job 1.15). R. Abba bar Kahana said: They went from Kefar Kernos, and through all the Aulon and reached Migdal Zaba'ayya and died there. `And only I escaped to tell you' (ibid.): R. Yudan said: Wherever (in scripture) it is said `only', it implies a restriction. He (the messenger) too, was broken and stricken. R. Yudan said... and he too, as soon as he told his message, immediately died... `While he was still speaking, another messenger came and said: The Chaldeans formed three raiding parties [and swept down on your camels and made off with them] (Job 1.17). R. Samuel b. Nahman said: As soon as Job heard this he began marshalling his warriors... (but) when he was told `A fire of God is fallen from heaven' (Job 1.16) he said: What can I do. A voice has fallen from heaven! Who can do anything? ...32What is the meaning of this ambiguous midrash? And why does it elaborate on a journey of Jobs' servants through sites that are not mentioned either in the story or in the Bible in general? It seems that the rabbis are alluding to events in these places that were known to their contemporaneous audience but whose meaning is hidden from us today.33 In any case, two of the places mentioned here can be clearly identified: Kefar Kernos is mentioned in the Talmud Yerushalmi and in the halachic inscription from the Rebov synagogue, both pointing to a village adjacent to Beth Shean.34 Aulon is mentioned in the Septuagint (Deut. 1.1, Hebrew Hazeroth) and is identified in the Onomasticon of Eusebius as follows:

The great long plain is still called the Aulon (Aviv). It is bordered on both sides by mountains extending from Lebanon to the desert of Pharan. In the Aulon is the famous city [Tiberias] and nearby the lake, Scythopolis, Jericho and the Dead Sea and their surrounding regions. The Jordan flows through the midst of the whole region....35Thus, the Aulon is what is called today the Jordan Valley. According to the story, Job's servants began their journey near Beth Shean, passed through the Jordan Valley and all but one died at Migdal Zaba'ayya, again indicating that this village is located somewhere in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee. In this context, it should be noted that a tradition appearing in the Babylonian Talmud, and in some manuscripts of Genesis Rabbah, states that Job lived in Tiberias.36 This may be the reason for the development of our story focusing on sites in this region. It is not clear why Migdal Zaba'ayya was chosen as the servants' death-place. The tradition, brought by R. Abba bar Kahana who lived in the Galilee in the late third—early fourth centuries CE, may allude to a known tragedy that occurred in that village, such as the early second-century destruction mentioned above or perhaps an earthquake (the `fire of God fallen from heaven' at the end of the story?). The excavations at Kh. Wadi Hamam revealed evidence of two destructive episodes that seem to be the result of earthquakes, the first in the late third or early years of the fourth century CE, and the second in the year 363 CE (see Chapters 2, 6).

In conclusion, Migdal Zaba'ayya should be situated somewhere near the Sea of Galilee, apparently not too far from Tiberias. The clues in the literary sources as to its location and events that took place there, are consistent with the location of Kh. Wadi Hamam and its history, as revealed in our excavations. At this stage in the research, however, this identification must remain a plausible suggestion.

7 Rhode 1979: 88.

8 Conder and Kitchener 1881: 409.

9 British Mandate Department of Antiquities Archive,

SRF 192 (7/7) and Jacket ATQ 1045 (3/3).

10 This suggestion was first raised in my Ph.D.

dissertation (Leibner 2004: 218–226), but later I

proposed identifying Migdal Zabaʿayya with a

different site, south of Tiberias (Leibner 2006).

The excavation results, however, have led me to

return to my initial suggestion.

11 Various identifications have been suggested by

scholars for this site, all in the vicinity of the Sea

of Galilee, see, e.g., Schwarz 1979: 228; Graetz

1880; Press 1930: 255–268; 1961: 162–170; Klein

1967: 199–201; Feliks 1981: 22. The suggestion of

Taylor (2014: 209–210) that the site be sought in

the vicinity of Jerusalem does not stand up to

scrutiny.

12 For a detailed discussion on the identification of

Migdal Nunayya/Magdala/Tarichea and the

etymology of the names, see de Luca and Lena

2015: 280–298, with references therein.

13 Neubauer 1868: 217; Press 1930; 1961: 164;

de Luca and Lena 2015: 289.

14 In the parallels (Yerushalmi Sheviʿit 9.1 [38d];

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 11.16 [ed. Mandelbaum,

p. 193]; Kohelet Rabbah 10.8), the reading is

Magdala.

15 In some mss.: Beth Netofa / Beth Tifa.

16 Translation (with modifications) after Levine

1978, who provides a detailed comparison

between the parallel traditions and an extensive

discussion of the story.

17 A parallel with small variations appears in

Yerushalmi Pesahim 4.1 [30d].

18 Feliks 1981: 22.

19 See Yerushalmi Berakhot 7.3 [11b]; Moʿed Katan

3.5 [82c]; Terumot 8.3 [45c]; see also Beer 1983:

80–82; Rosenfeld 1998: 57–103.

20 Apparently from [Greek text], here meaning

revenue or donations.

21 Palgas, perhaps from [Greek text] — a cloak, see

Sperber 1993: 132–140.

22 A similar tradition, which apparently developed

from this source, appears in Lamentations Rabbah

2.2 (Buber edition p. 54): R. Huna said: There were

three hundred stores selling [food preserved in

the condition of] cultic cleanness in Migdal

Zabaʿayya …

23 Tsafrir et al. 1994: 102; Strange et al. 1995.

24 Press 1930; 1961: 164.

25 War 2.505.

26 Klein 1967: 50.

27 For Tur Shimʿon and Har ha-Melekh, see Zissu

2008 and Shahar 2000, respectively.

28 See the relevant entries in Tsafrir et al. 1994:

102, 70, 173.

29 The ancient Jewish text dubbed Toledot Yeshu

presents a derogatory version of the life of

Jesus. Interestingly, in the Aramaic version of

the text, presumably originating in the

Byzantine period, in a scene set in the

vicinity of Tiberias, John the Baptist is

called limn= pni, (Deutsch 2000: 186, Lines 4,

9, 15). This nickname is usually translated as

John the Dyer and is thought to be an

unarticulated use of the verb vn2 (Zab`a),

which means to dye but also to dip/immerse,

hence to baptize (idem.: 179). However, the

prefix h is usually used to designate the

place of origin, and could be understood as

John from Zaba'ana.

30 Genesis Rabbah 19.1 (ed. Theodor-Albeck

p. 170); see also Ilan and Izdarechet

(1988: 36), who suggest that pools identi-

fied at Arbel were used in flax processing.

31 For example, Yerushalmi Ma'aser Sheni 5.2

(56a); Kohelet Rabbah 1.8 (Hirshman ed.

p. 64).

32 Translation (with modifications) after

Freedman and Simon 1939: 217-218.

33 For a detailed discussion of this midrash,

see Leibner 2006: 41-49.

34 Yerushalmi Demai 2.1 [22c]; Sussmann

1973-74: 158; see also Leviticus Rabbah

28.6 (ed. Margulies p. 666); Yahalom and

Sokoloff 1999: 208-210.

35 Onomasticon, ed. Klostermann, p. 14.

Interestingly, in the Latin translation

(idem.: 15) Jerome emphasizes that Aulon

is not Greek, as one might think, but rather

a Hebrew word.

36 Bavli Bava Batra 15a; Genesis Rabbah 57.4

(ed. Theodor and Albeck, p. 617) according

to mss. Oxford 147, Oxford 2335, Paris 149.

The current section presents a stratigraphic synthesis focusing on the main terrace and the monumental buildings that stood on it, based on the details and archaeological finds discussed above

Limited restoration works in Synagogue II at the end of the fourth century were labeled Sub-Phase IIb, and include the addition of three stratigraphically related features: (1) a stone bema; (2) a low bench added against the southern wall; (3) a plaster floor, which replaced damaged portions of the mosaic. The cause and date of the damage that necessitated this renovation could not be precisely determined, but it clearly occurred in the late fourth century. The most plausible event is the earthquake of 363 CE, which was apparently responsible for the destruction of some of the surrounding domestic structures and devastated many sites in the region (see Chapter 6).19

No traces of a bema attributable to Synagogue I or II were detected, although we must admit that the southern part of the synagogue is poorly preserved. The fact that the bema of Sub-Phase IIb was built directly upon the mosaic floor certainly indicates that no stone-built bema stood here in Phase II. Remains of the mosaic found in the southeastern part of the nave similarly preclude the option that a bema stood on the other side of the main entrance in Phase II. In other synagogues in the region, such as Hammat Tiberias, a stone-built bema was also added in the fourth century where previously none had existed.20

The bema and the low bench added in Sub-Phase IIb are constructed of reused architectural elements and are poorly and sloppily executed, reflecting the decline of the synagogue. Similarly, the replacement of large portions of the mosaic with a plaster floor attests that at the time of the renovation, the community lacked the means to repair or replace the mosaic. It is noteworthy that despite the heavy damage, the surviving mosaic segments were preserved and not plastered over, evidence that they were considered sufficiently important to be preserved as much as possible (no other such instance of the ancient preservation of a synagogue mosaic is known to date). This situation is consistent with the general picture revealed in the excavations that by the late fourth century, most of the village was already deserted

19 For archaeological evidence of the earthquake of

363, see Russell 1980; Balouka 1999

20 Dothan 1983: 31–32;ugeneral, Weiss

1988.

The debris in the northwestern quarter of the synagogue hall, which had accumulated to a maximal height of ca. 2.2 m above floor level, provided important information concerning the last stage of the building and its final collapse. The components of the corner column had fallen to the southwest, and courses of blocks from the walls, still bound together by mortar, were discovered lying on their sides among the debris. In the debris were hundreds of roof tiles and dozens of large construction nails that probably originated from the truss that supported the tiled roof. All this evidence seems to imply that the final collapse was caused by an earthquake. The latest pottery and small finds on the floor beneath the debris date to the fourth–early fifth centuries. These finds were probably washed in from above after the abandonment of the building, but before its collapse, and seem to have been sealed inside shortly thereafter, since no material of later date was recovered on the floor. Thus, the building probably collapsed in an earthquake in the early years of the fifth century (perhaps in 419?).21 The similarity between the material beneath the debris and that found inside the bema indicates that the renovations in Sub-Phase IIb took place shortly before the destruction of the building. As noted above, the two successive plaster floors in some places suggest two stages of renovation in this sub-phase.

21 The earthquake of 419 is mentioned in the Chronicon Marcellini (Mommsen 1894: 74); see also Russell 1985: 42–43; Amiran, Arieh and Turcotte 1994: 266.

A few finds provide evidence of limited activity that took place in and around the synagogue after its collapse. The nature of the finds, the small quantity and their location, indicate that these were sporadic activities reflecting stone robbers, squatters, or passersby who visited the site.

On the alley surface to the north of the synagogue, a pottery assemblage of the late fourth–early fifth centuries was recovered, and some of the vessels were restorable. As the domestic structures to the north had apparently collapsed in the earthquake of 363 CE, this strange location for pottery vessels suggests squatters making use of the alley after the surrounding structures, and perhaps also the synagogue, had gone out of use. A number of Umayyad-period oil lamps, as well as a Mamlukian painted jar, were found beneath the collapsed vault in Room A6, evidence that this room survived long after the village and its synagogue were abandoned. In the corridor on the upper terrace to the west (Unit A9), two consecutive tabuns were built against the outer face of the synagogue’s wall on a layer of collapsed stones. This odd location, and the fact that the tabuns were constructed of tiles originating from the synagogue roof, demonstrate that they were built after the synagogue went out of use. Two sixth-century coins found nearby suggest a Late Byzantine date for this activity.

An eighth-century coin from the debris of the eastern wall may point to stone robbery during the Umayyad period (L.5A007; Cat. No. 373). Similarly, a 1949 coin found immediately above the floor in the southern part of the nave, and a few audio cassettes recovered nearby, attest to activity and perhaps stone robbing in the twentieth century as well.

The plan and function of this area in Stratum 3 is unknown as only two of the walls here can be attributed to that period (W3B02, W3B03), and in both cases, it appears that our excavation only exposed their exterior faces. The abundant Early Roman finds, however, point to some activity here or in the immediate vicinity in that period. The complex as described above clearly belongs to Stratum 2 (Fig. 6.14), and the coherent plan and homogenous finds seem to indicate that all the units were built and functioned contemporaneously. Furthermore, as no changes or restorations were discerned, the entire complex apparently had only one phase. The entrances to the dwellings on both sides of the courtyard had lockable doors, suggesting that distinct families lived on either side of a shared courtyard. As the southern wall of the courtyard was not exposed, we may speculate on the existence of an additional structure that opened onto this courtyard.

While a precise date for the construction of this complex could not be determined, the few finds in loci beneath the floors (e.g., L.5B018 in Unit B2) suggest sometime within the course of the third century. The latest finds in all the units indicate that the entire complex was abandoned around the mid-fourth century CE. The latest coin dates to 351–361 CE (Cat. No. 301), hinting of a connection with the earthquake of 363 CE. However, as no restorable pottery or implements were recovered, it seems that the structure was deserted in an organized manner, and not as a result of a sudden catastrophe.

The area south of the oil press was excavated in the 2007 and 2008 seasons, starting with a 5.5 × 5 m square to the south of W1B04 and east of W1B01 (Units B7–B8), followed by an adjacent 4 × 4 m trench to the southwest, on both sides of W2B02 (Unit B10; Figs. 6.2, 6.29). As in Units B5–B6, excavation here revealed a Stratum 2 structure built on a huge fill that totally buried a Stratum 3 house up to the top of the first floor. The area consists of a dense series of walls belonging to both strata (see Fig. 6.1). Due to space limitations and safety constraints, the excavation reached the floor level of the Stratum 3 structure only in Unit B7. In general, the walls of the Stratum 3 structure are similar in building technique to the other structures of this stratum: they are founded on the talus slope and built of two faces of large fieldstones or partially dressed stones, of both basalt and hard limestone, with small stones in between them. The walls of Stratum 2, on the other hand, are built mainly of small stones and ‘float’ on the debris with almost no foundation courses beneath floor level.

In Stratum 2, Unit B7 consists of a rectangular room (4.6 × 3 m, inner dimensions) bordered on the north by W1B04, on the east by W2B06, on the south by W2B01 and on the west by W1B01. The northern and eastern walls are bonded in the northeastern corner and abut the southern and western walls that are bonded in the southwestern corner. The walls are preserved to a height above floor level of ca. 1.3 m in the west and 0.5 m in the east. Although it is evident that the builders were familiar with the subjacent Stratum 3 walls, they did not construct their walls on top of them, but rather on top of the debris. A seam is clearly seen in W1B01, and to the south of it the wall is built on the debris (Fig. 6.30), suggesting that the southern part of this wall is a Stratum 2 addition (see below).

Following removal of the dark topsoil (L.1B009), a collapse of building stones appeared (L.1B012, L.2B004, L.2B008, L.2B011). While dismantling the collapse, the tops of W2B05 and W2B07, which were buried within it, were revealed. No clear floor of the upper structure survived, but it seems to have been at a similar elevation as the floor of the adjacent Unit B6 (ca. 100.20 m asl). The pottery from the collapse in the above-mentioned loci resembles that found in the oil press in Unit B6 and includes mainly fourth-century pottery (see Chapter 9: Pl. 9.21:1–7).

In Stratum 3, Unit B7 is bordered by W2B05 in the north and W2B07 in the east, which bond at the corner. The outer corner is abutted from the north by what might be the continuation of W1B05. The eastern wall (W2B07) curves slightly towards the east, perhaps a result of an earthquake or pressure caused by collapsed debris. The northern wall runs below W1B01 to the west, and the closing wall of the lower structure must be further to the west. The room is closed on the south by W2B08, exposed in the adjacent square, hence the inner width of the room is 4 m.