Khirbet al-Batrawy

Left

LeftAerial View of Khirbet al-Batrawy

Nigro (2008)

Right

Aerial View of Khirbet al-Batrawy

APAAME 20141012 REB-0046 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet al-Batrawy | Arabic | |

| The City Of Copper Axes | English |

- from Nigro (2024:61)

- foundation at the beginning of Early Bronze II (3000 BC)

- collapse caused by a severe earthquake at the end of the period (2800 BC)

- urban floruit during the Early Bronze IIIA–B (2800–2500 – 2300 BC)

- final destruction due to a fierce conflagration at the end of Early Bronze IIIB

- reoccupation of the ruins by an Early Bronze IVB rural village (2200–2000 BC)

The city of Khirbet al-Batrawy represents a rare example of an early urban centre arising in a peripheral area of the ancient Near East at the dawn of urban civilization in the 3rd millennium BC. The discovery of Batrawy in 2004 by the Expedition to Jordan of Rome «La Sapienza» University and the discovery of its Royal Palace in 2009 opened up new perspectives on the settlement of these fringe regions, especially in the period before the domestication of the camel.

The site of Khirbat al-Batrawy, the previously unknown city of the third millennium BC discovered in 2004, has been systematically explored by the Expedition to Palestine & Jordan of Sapienza University of Rome since 2005. Archaeological investigations and restoration works were carried out under the aegis of the Department of Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, with the support of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation and the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research.

Batrawy was founded as the outcome of a synecistic process which characterized the early urban phenomenon in the Southern Levant. The EB II-III (3000-2300 BC) city was in a strategic position, at the same time, for the exploitation of cultivable land and water resources, and for long-distance trade network connecting the site of Batrāwī with the main urban civilizations of the third millennium BC. The discoveries in the “Palace of the Copper Axes” revealed the central role played by the fortified city of Batrāwy at the junction of the east-west route which crosses the Syro-Arabic Desert to Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula and the south-north main route, later on named "King's' Highway", running upon the Jordanian Highlands from the Sinai, the Gulf of ‘Aqaba and Wadi 'Araba.

The planning activities for exploration on the northern slope of the site (Area B North) moved from the discovery in 2009 of the Royal Palace (the "Palace of the Copper Axes"), a public building of the 3rd millennium BC which has provided a wealth of data and findings in an extraordinary state of preservation. A second aim of the Expedition has been the exploration of the well-preserved massive fortification system, just north of the Royal Palace. The excavations revealed quadruple lines of fortifications with its projecting towers and bastions.

- Khirbet al-Batraway in

OSM from Pleaides

Khirbet al-Batraway location in OSM (Open Street Map)

Khirbet al-Batraway location in OSM (Open Street Map)

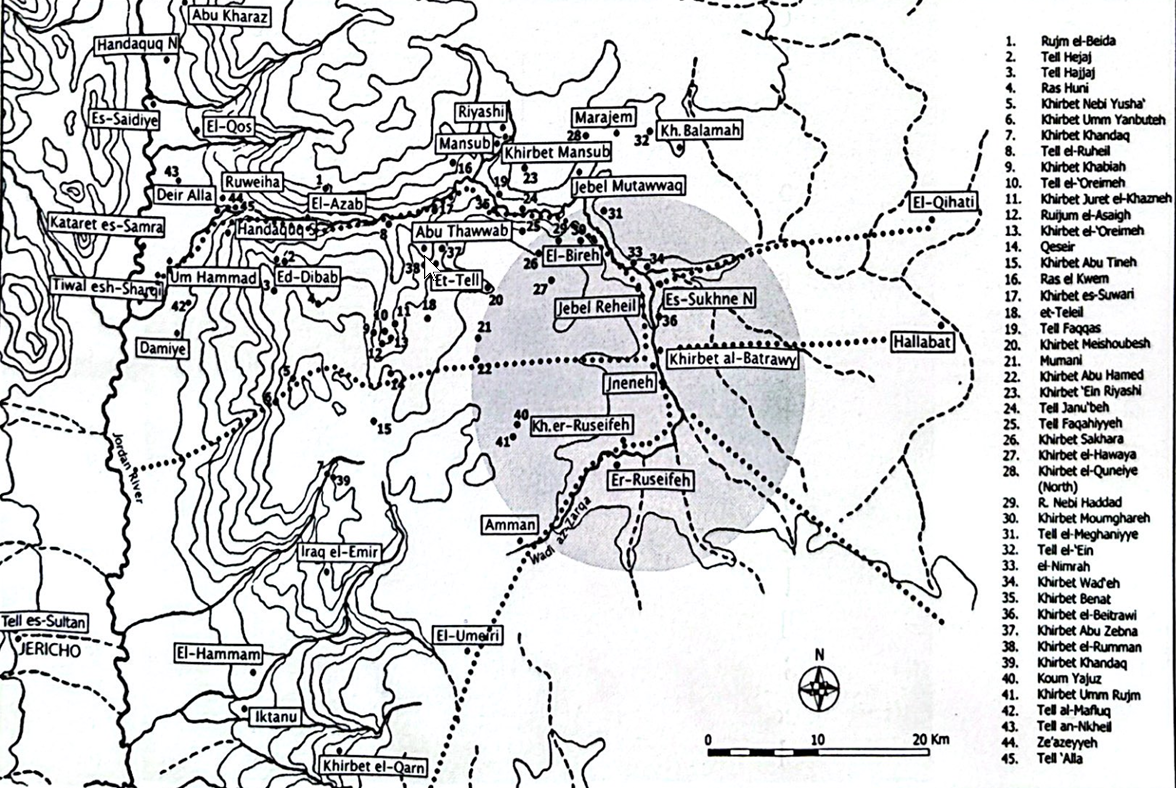

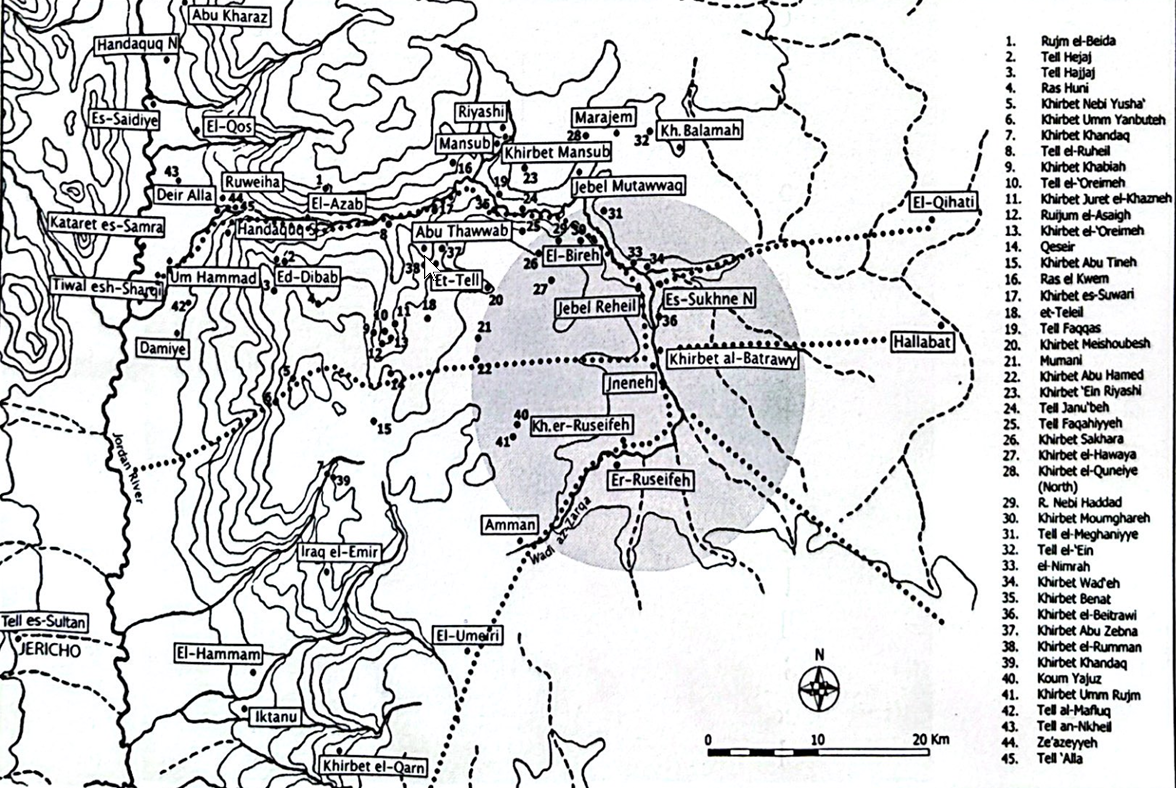

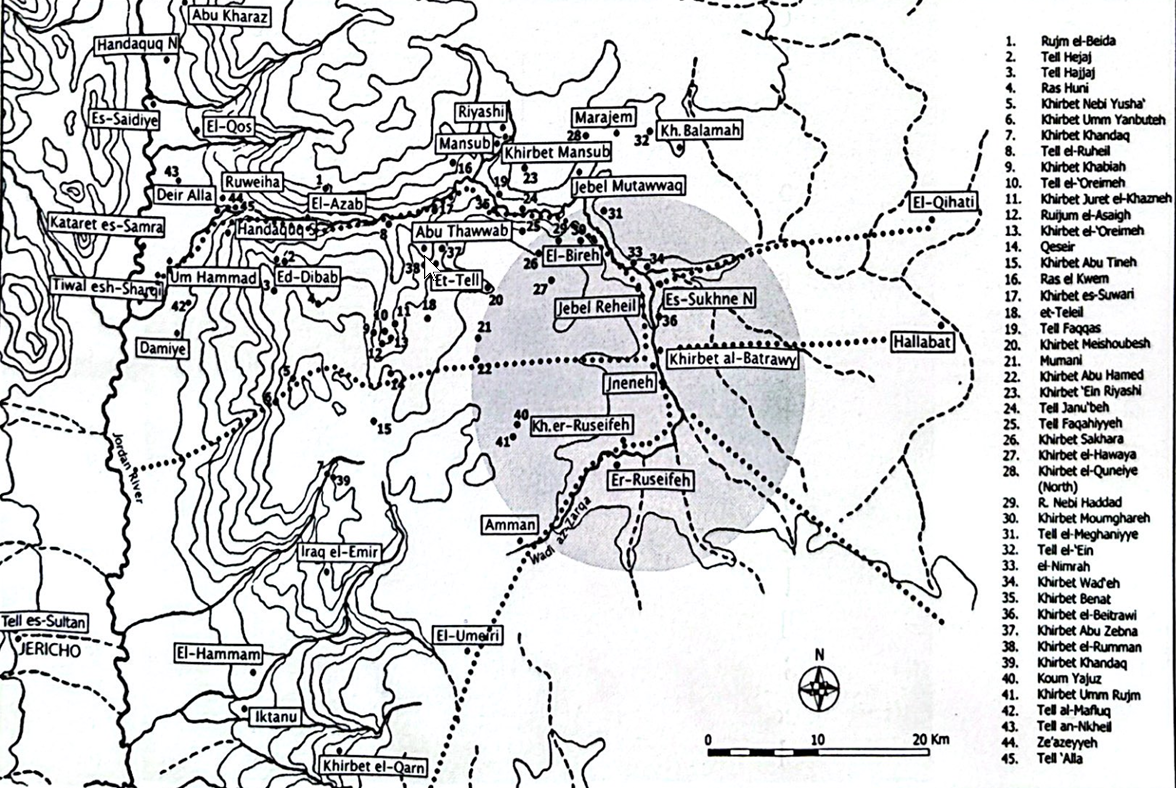

Pleaides website - Fig. 2 Map of Upper

and Middle Wadi az-Zarqa with visited Early Bronze Age sites, dolmens and archaeological feature from Nigro (2008)

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5

Topographical map of Upper and Middle Wadi az-Zarqa with visited Early Bronze Age sites, dolmens and archaeological features detected during 2007 survey.

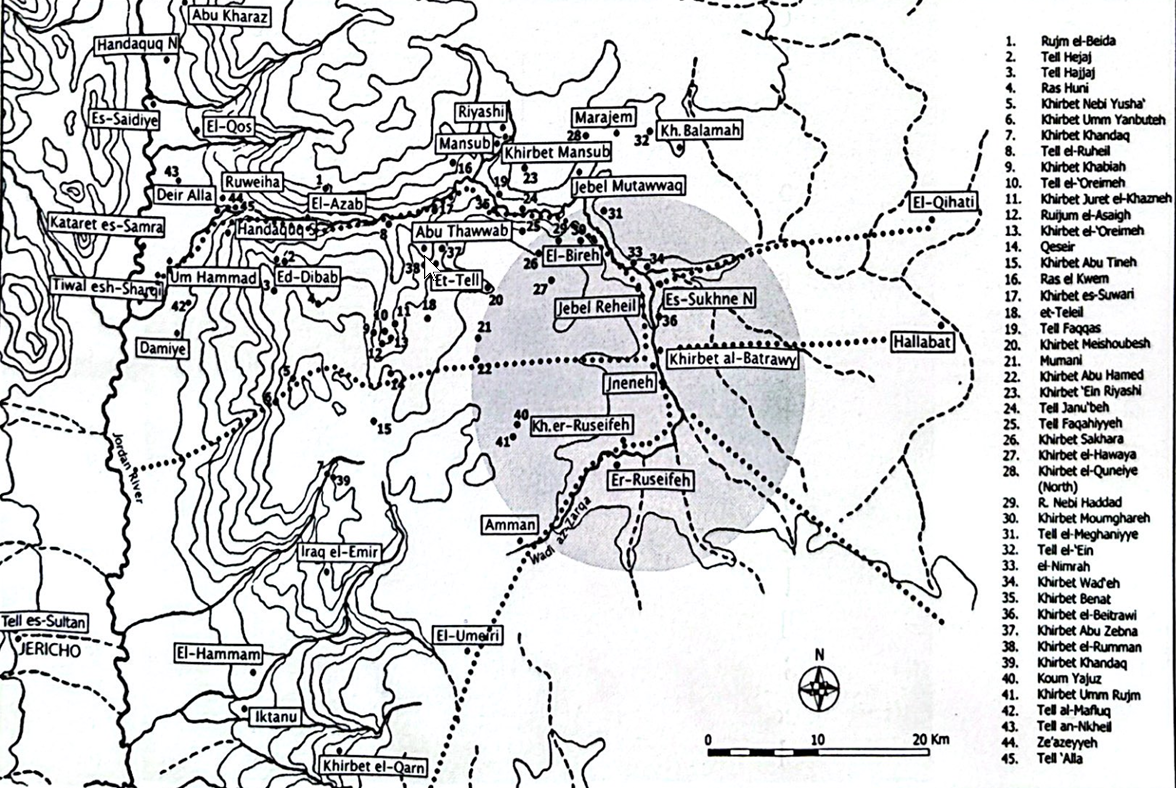

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 2 Map of region

of Al Batrawi with the contemporary sites from Nigro (2025)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the region of Al Batrawi with the contemporary sites of the area under the city's influence

Image "La Sapienza" Expedition to Jordan

Nigro (2025)

- Khirbet al-Batraway in

OSM from Pleaides

Khirbet al-Batraway location in OSM (Open Street Map)

Khirbet al-Batraway location in OSM (Open Street Map)

Pleaides website - Fig. 2 Map of Upper

and Middle Wadi az-Zarqa with visited Early Bronze Age sites, dolmens and archaeological feature from Nigro (2008)

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5

Topographical map of Upper and Middle Wadi az-Zarqa with visited Early Bronze Age sites, dolmens and archaeological features detected during 2007 survey.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 2 Map of region

of Al Batrawi with the contemporary sites from Nigro (2025)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the region of Al Batrawi with the contemporary sites of the area under the city's influence

Image "La Sapienza" Expedition to Jordan

Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 3 Aerial view of

the ancient territory under Batrawy control from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Aerial view of the ancient territory under Batrawy control, inside the big turn towards west of az-Zarqa river.

Nigro (2008) - Khirbet al-Batrawy in Google Earth

- Fig. 1.2 Topographical

plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy from Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2

Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007).

Nigro (2008)

- Fig. 1.2 Topographical

plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy from Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2

Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007).

Nigro (2008)

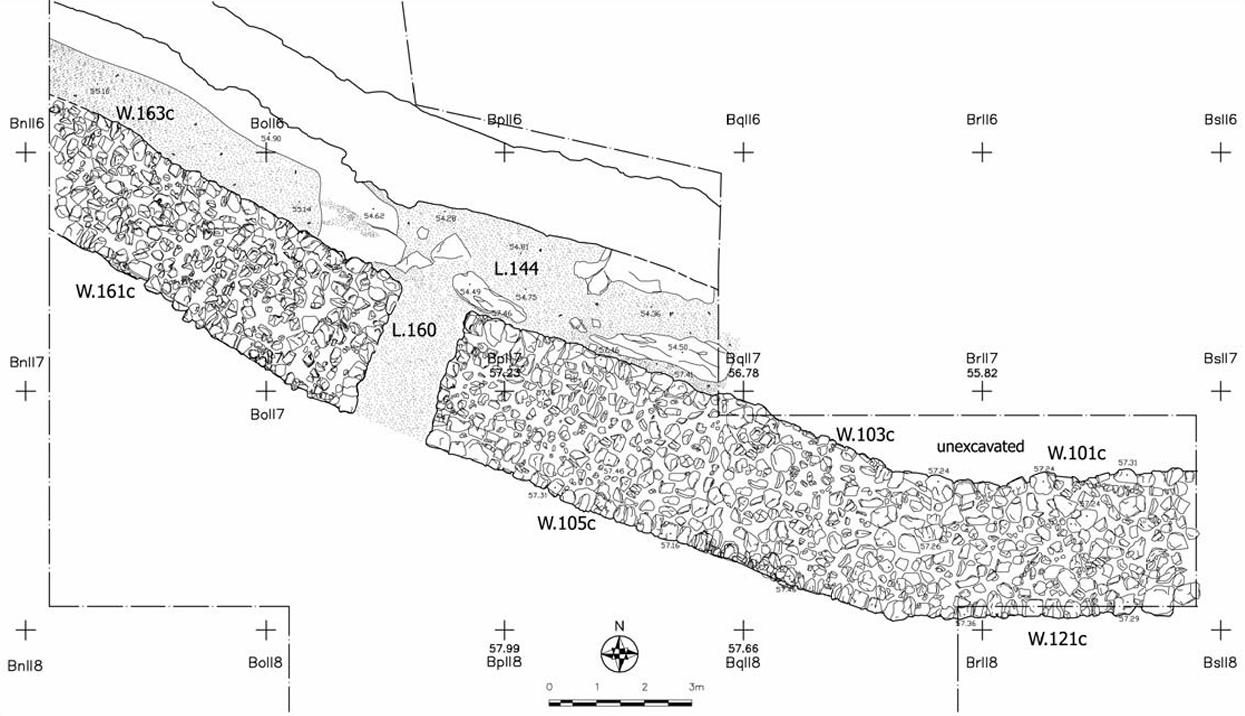

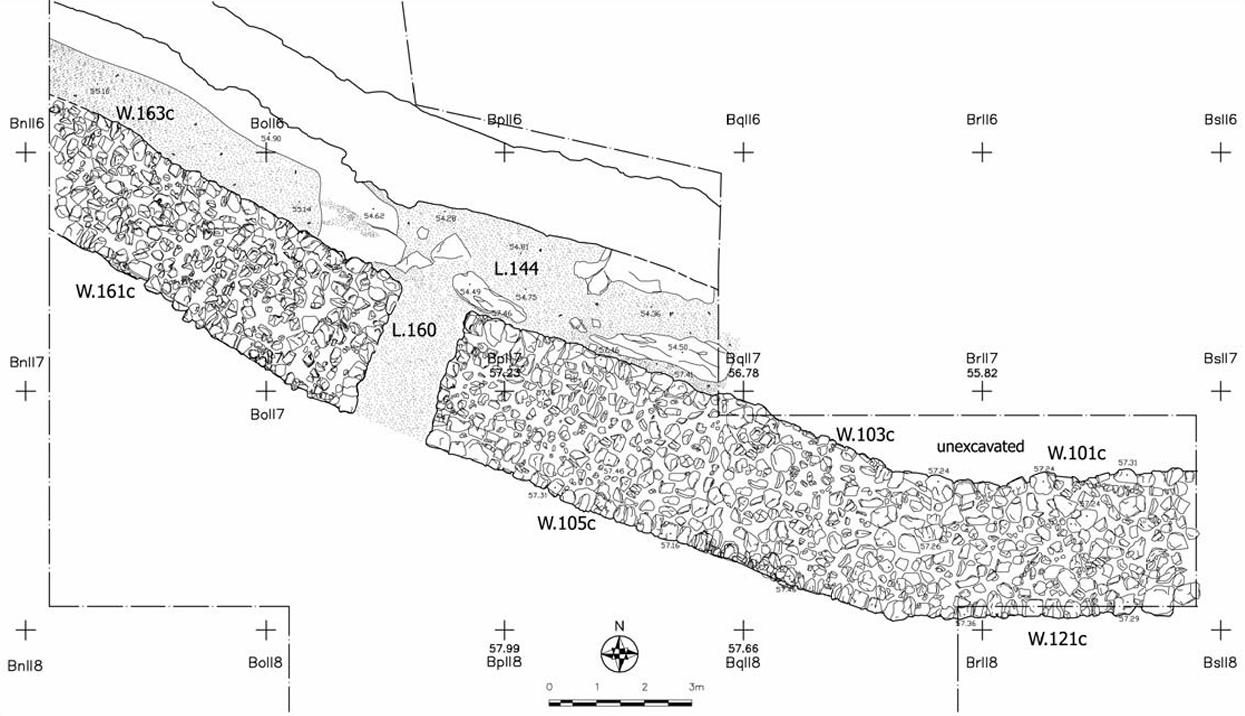

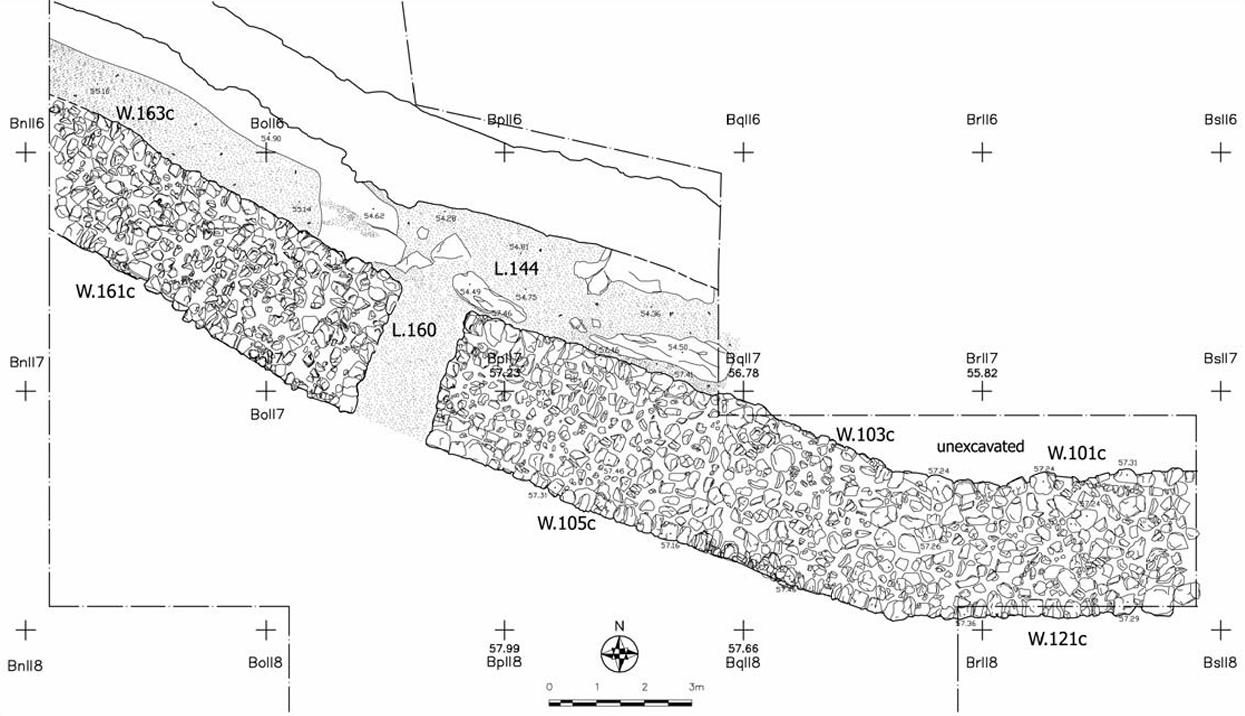

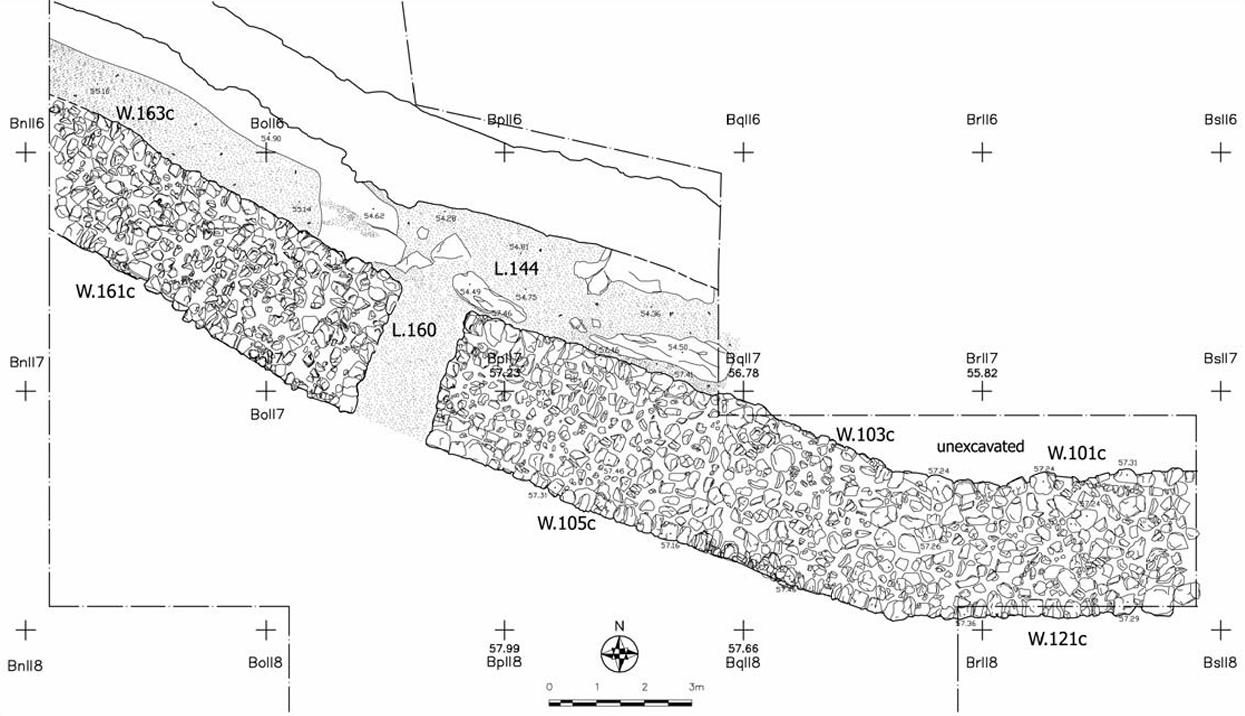

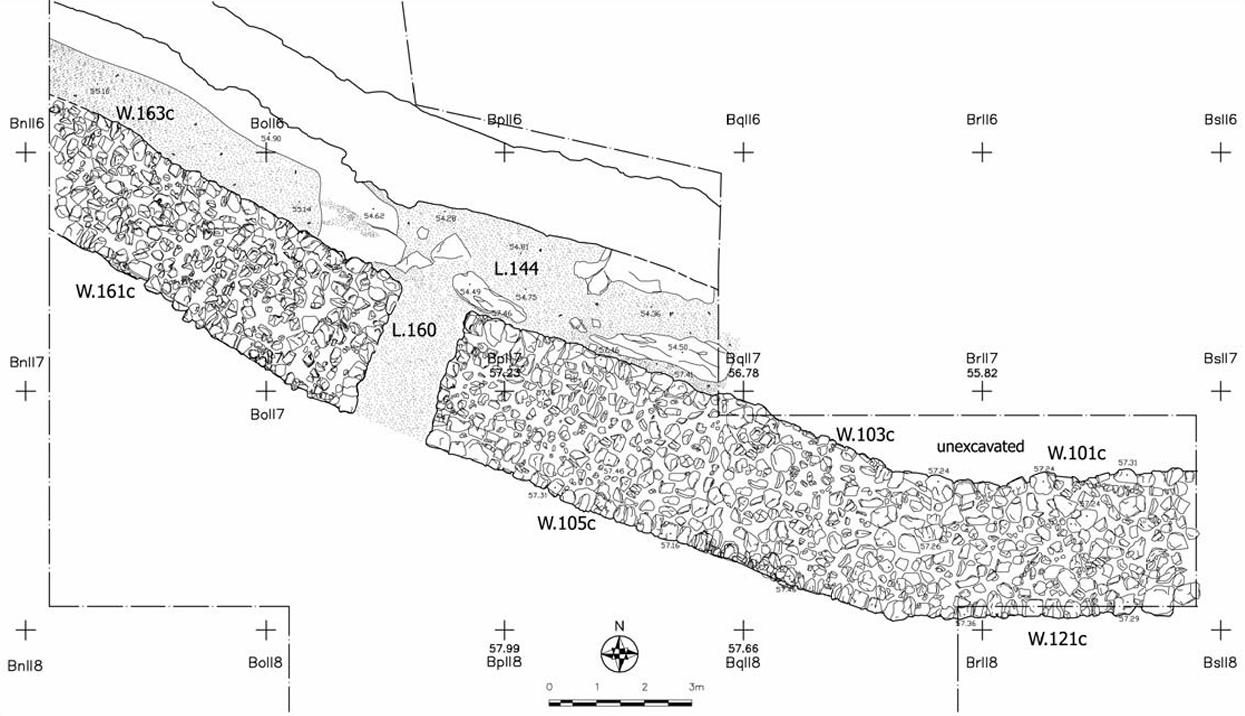

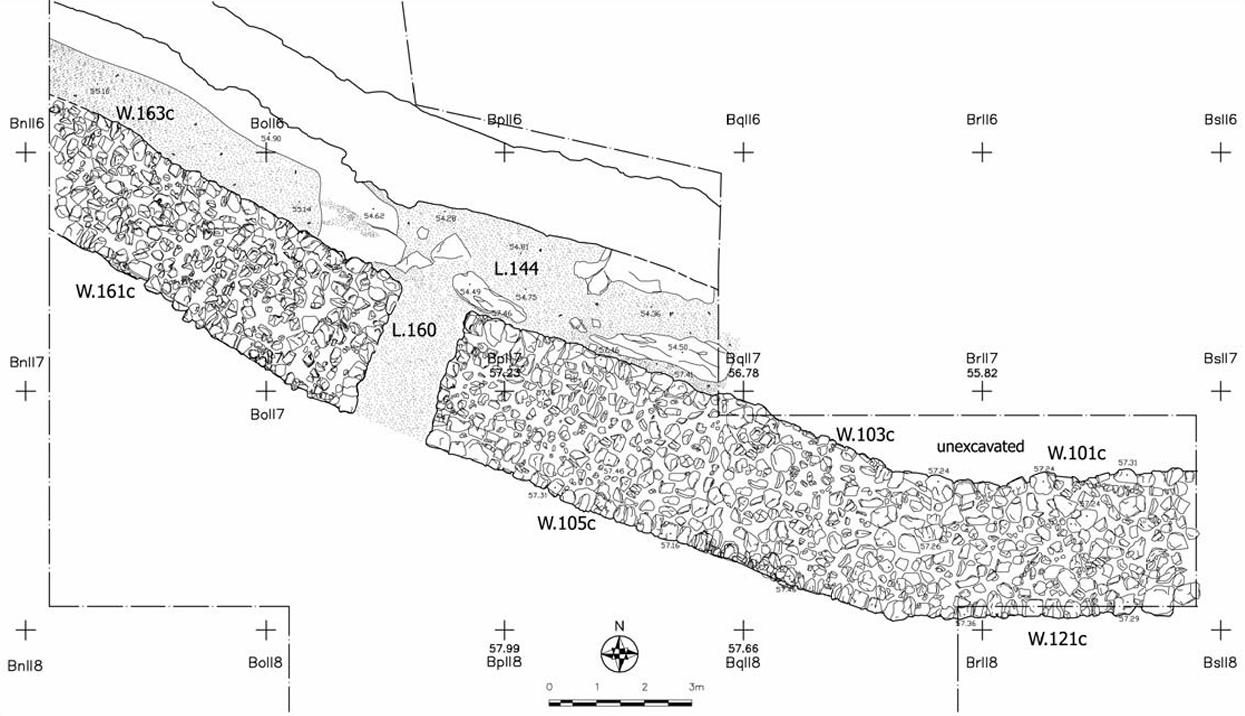

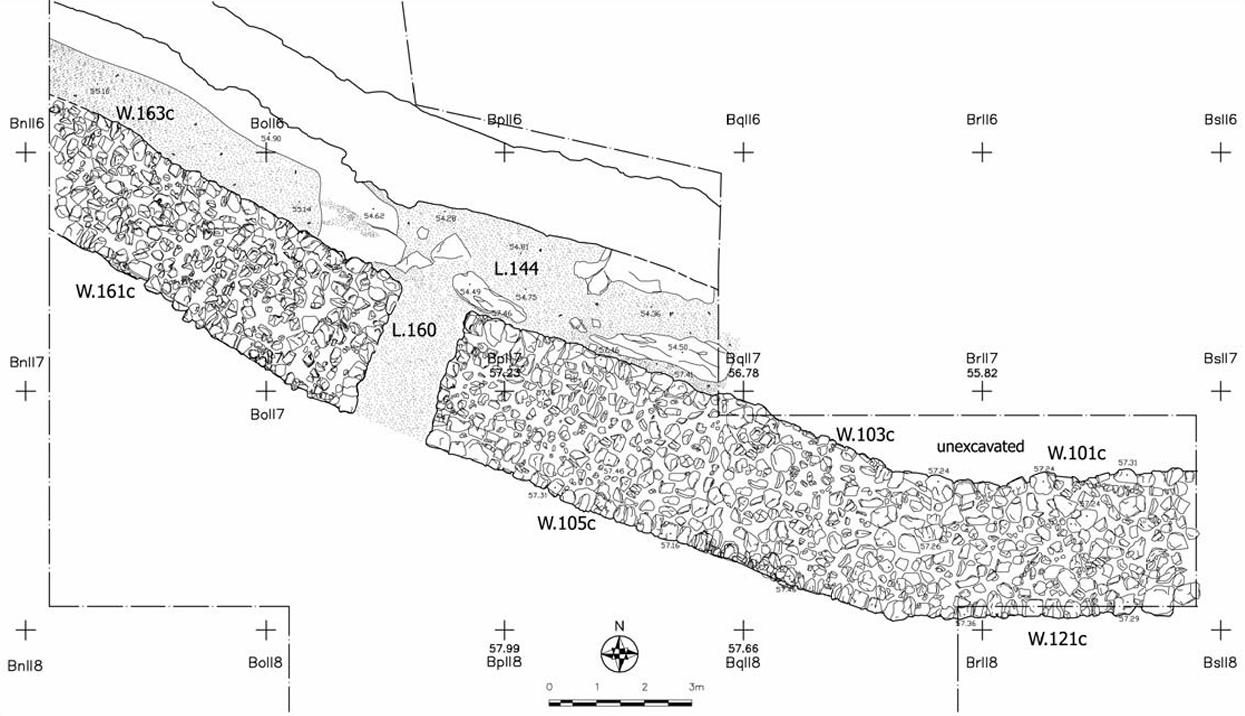

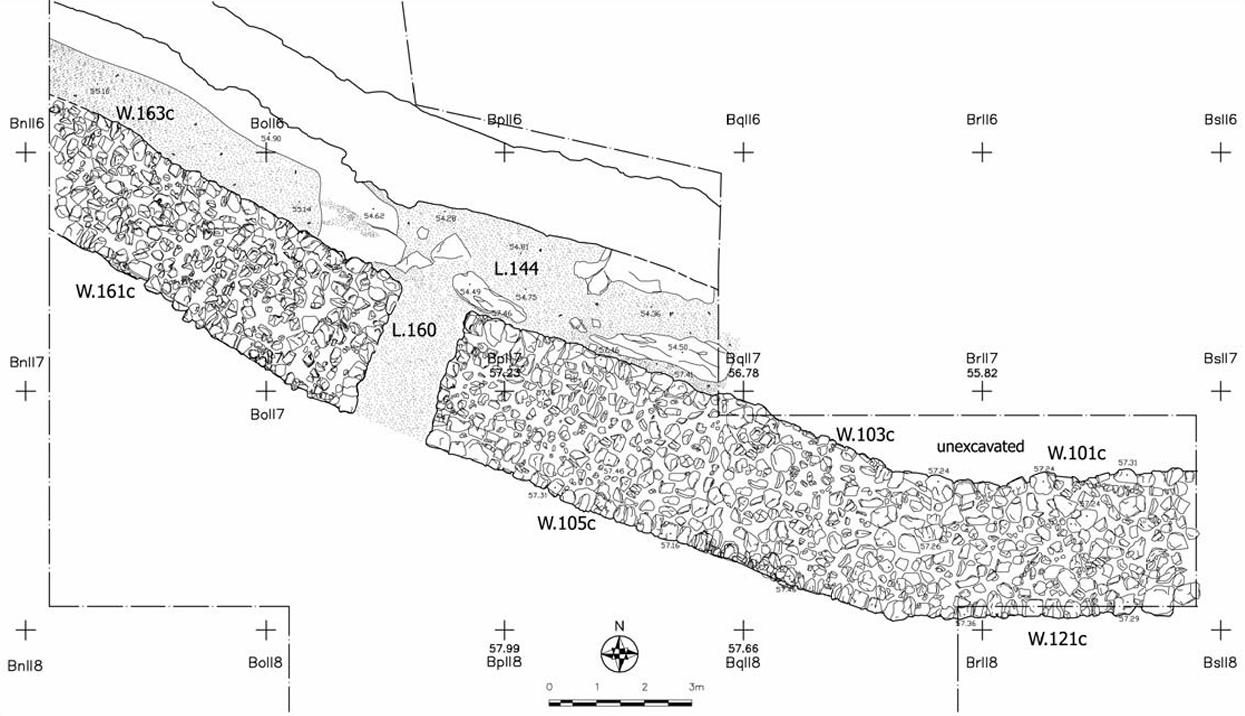

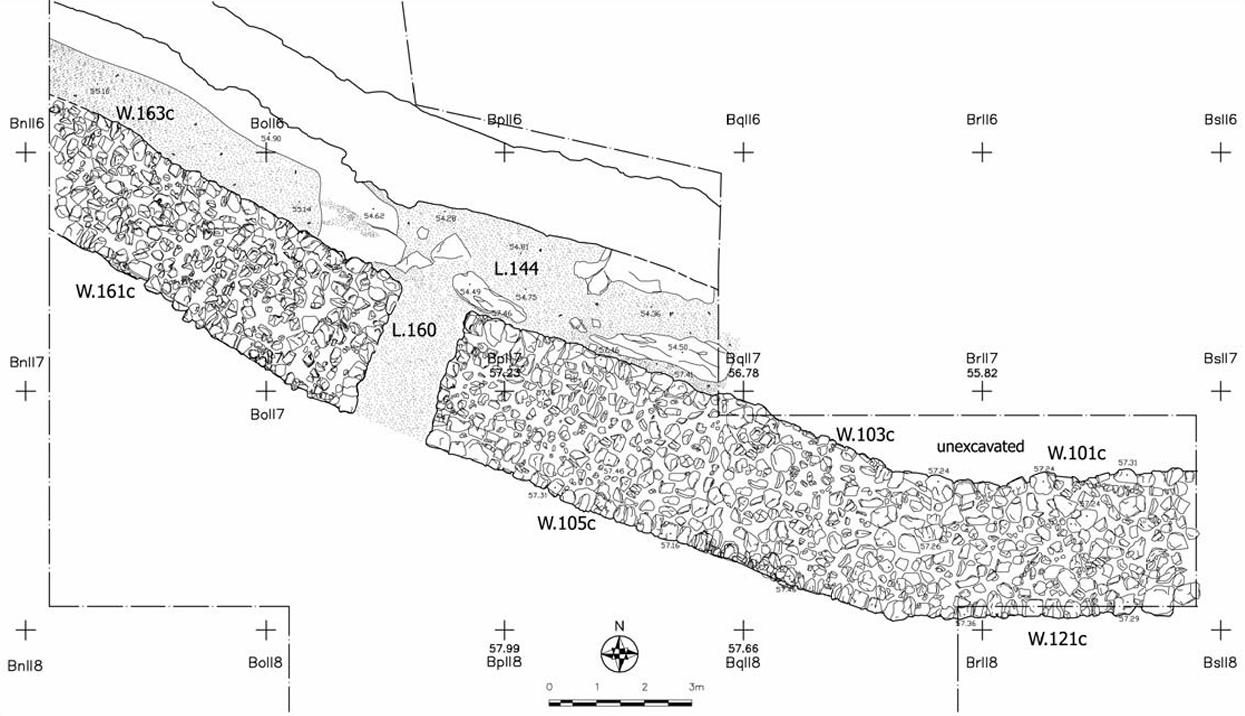

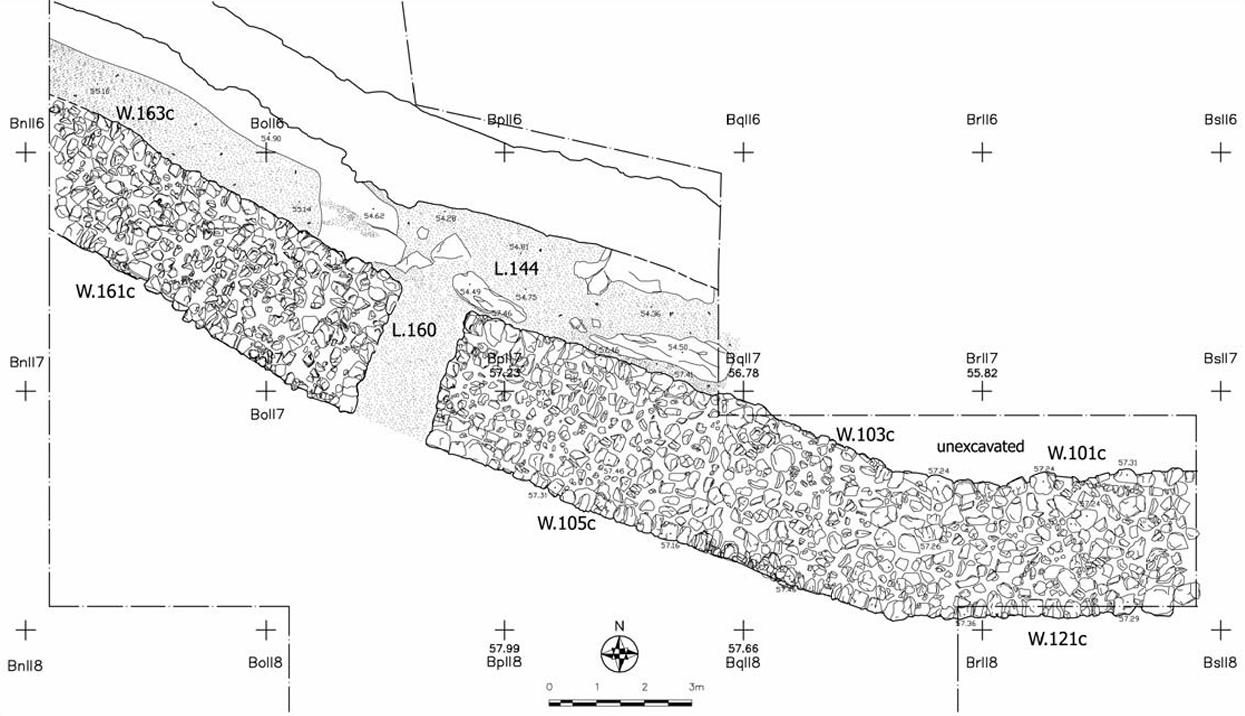

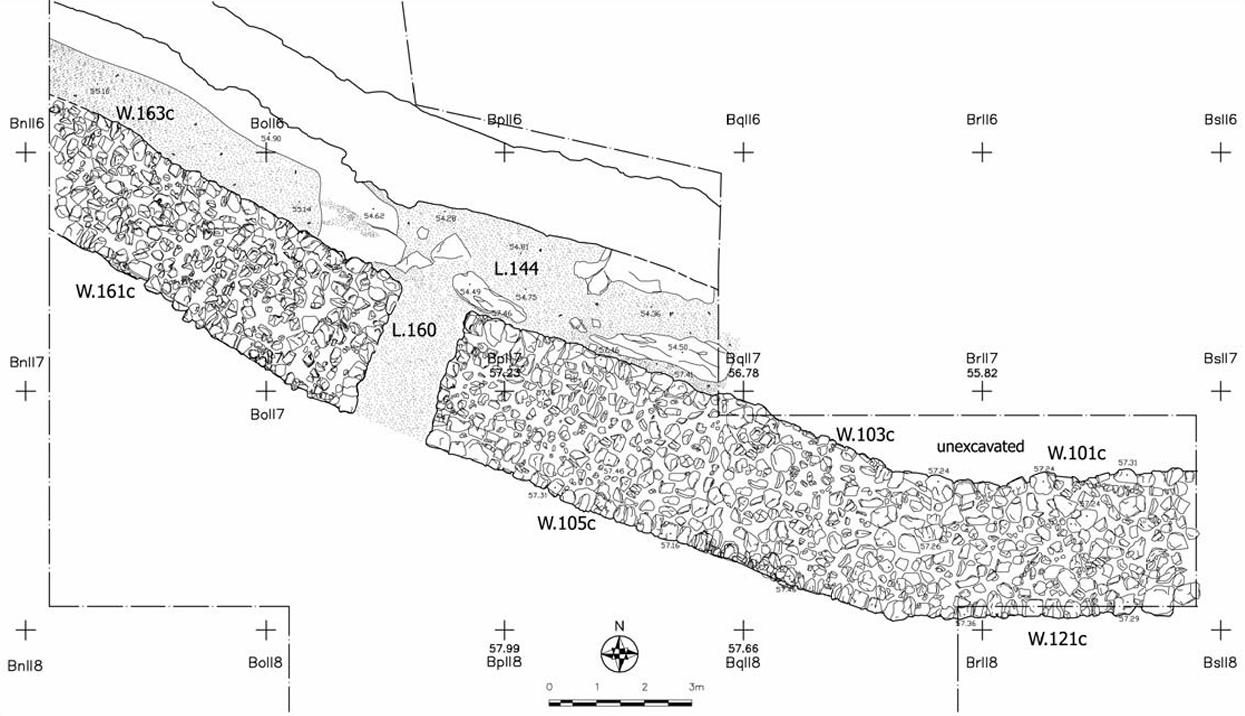

- Fig. 3.19 EB II city-wall

and gate from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19

Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.23 Schematic

reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23

Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall.

Nigro (2008)

- Fig. 3.19 EB II city-wall

and gate from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19

Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160.

Nigro (2008)

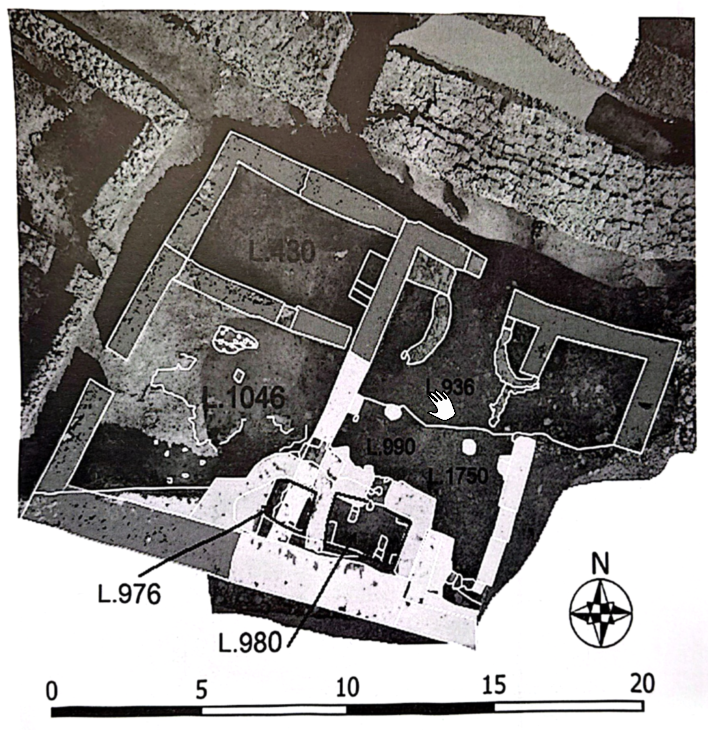

- Fig. 5 Plan of the

South-Eastern Unit of the Eastern Pavilion of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 5 Plan of the

South-Eastern Unit of the Eastern Pavilion of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 6.10 Plan of

Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city from Nigro (2008)

Figure 6.10

Figure 6.10

Plan of Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city.

Nigro (2008)

- Fig. 6.10 Plan of

Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city from Nigro (2008)

Figure 6.10

Figure 6.10

Plan of Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city.

Nigro (2008)

- Fig. 16 Reconstruction

of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II) from Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Reconstruction of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II)

Nigro and Sala (2009)

- Fig. 16 Reconstruction

of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II) from Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Reconstruction of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II)

Nigro and Sala (2009)

- Fig. 2.5 Collapsed

stones in Area A West from Nigro (2008)

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5

Area A West: the layer of collapsed stones F.232 (Activity 3a) in square BjII17, from south; in the background, Cairn II.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.18 EB II-III

fortification walls in Area B North from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.18

Figure 3.18

General view of the EB II-III triple line of fortifications excavated in Area B North, from north: W.103+W.163, the inner and main city-wall; W.155, the Outer Wall; adjoined Scarp-Wall W.165; in the middle, city-gate L.160 was excavated.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.24 Street along

the outer side of Batrawy II city-wall from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.24

Figure 3.24

Street L.144b along the outer side W.103c+W.163c of Batrawy II city-wall, from west.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.37 Earthquake

cracks on eastern jamb of city gate from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.37

Figure 3.37

Earthquake cracks visible on the eastern jamb (W.156) of city gate L.160.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.38 City Gate

after blockage (probable earthquake repair) from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.38

Figure 3.38

City-gate L.160 after the blockage (W.157) at the beginning of the Early Bronze IIIA, from north.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.7 Collapsed stones

in Area B South from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

General view of layers of collapsed stones F.352 and F.366 (Activity 2a) in squares BpII8 + BpII9, from south-east.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 7.7 Collapsed stones

in Area F from Nigro (2008)

Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7

Area F: layer of collapsed stones F.513 (Activity 2a) excavated in House L.520 in square CpII18, from south-west.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 15 EB II-III broad

room temple and round platform in Area F from Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 15

Figure 15

General view of the EB II - III broad room temple and round platform S.510 in Area F, from east-southeast.

Nigro and Sala (2009) - Fig. 3 Early Bronze Age

II-III Main Inner Wall (left) and Outer Wall (right) of northern fortifications from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 4 Early Bronze Age

II-III Main Inner Wall and Outer Wall of northern fortifications from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 6 South-Eastern

Unit of the Eastern Pavilion of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 7 Eastern wall

W.1737 of the South-Eastern Unit of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 8 Aerial view

of the South-Eastern Unit of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 2.5 Collapsed

stones in Area A West from Nigro (2008)

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5

Area A West: the layer of collapsed stones F.232 (Activity 3a) in square BjII17, from south; in the background, Cairn II.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.18 EB II-III

fortification walls in Area B North from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.18

Figure 3.18

General view of the EB II-III triple line of fortifications excavated in Area B North, from north: W.103+W.163, the inner and main city-wall; W.155, the Outer Wall; adjoined Scarp-Wall W.165; in the middle, city-gate L.160 was excavated.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.24 Street along

the outer side of Batrawy II city-wall from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.24

Figure 3.24

Street L.144b along the outer side W.103c+W.163c of Batrawy II city-wall, from west.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.37 Earthquake

cracks on eastern jamb of city gate from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.37

Figure 3.37

Earthquake cracks visible on the eastern jamb (W.156) of city gate L.160.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.38 City Gate

after blockage (probable earthquake repair) from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.38

Figure 3.38

City-gate L.160 after the blockage (W.157) at the beginning of the Early Bronze IIIA, from north.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 3.7 Collapsed stones

in Area B South from Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

General view of layers of collapsed stones F.352 and F.366 (Activity 2a) in squares BpII8 + BpII9, from south-east.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 7.7 Collapsed stones

in Area F from Nigro (2008)

Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7

Area F: layer of collapsed stones F.513 (Activity 2a) excavated in House L.520 in square CpII18, from south-west.

Nigro (2008) - Fig. 15 EB II-III broad

room temple and round platform in Area F from Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 15

Figure 15

General view of the EB II - III broad room temple and round platform S.510 in Area F, from east-southeast.

Nigro and Sala (2009) - Fig. 3 Early Bronze Age

II-III Main Inner Wall (left) and Outer Wall (right) of northern fortifications from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 4 Early Bronze Age

II-III Main Inner Wall and Outer Wall of northern fortifications from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 6 South-Eastern

Unit of the Eastern Pavilion of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 7 Eastern wall

W.1737 of the South-Eastern Unit of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

- Fig. 8 Aerial view

of the South-Eastern Unit of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" from Nigro (2025)

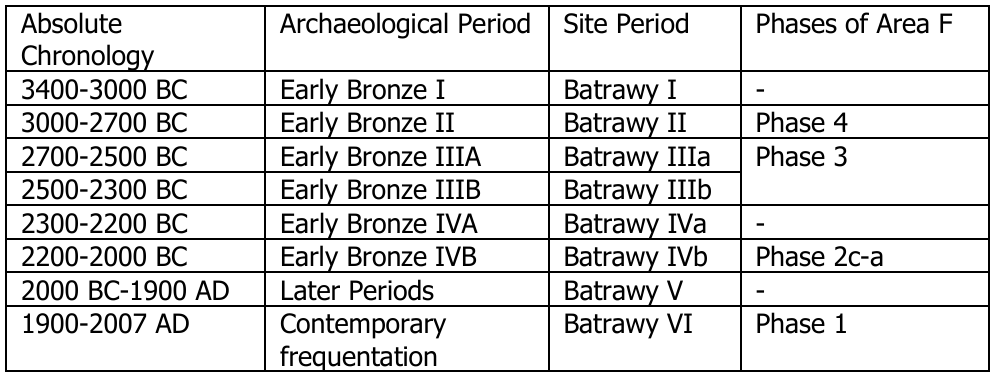

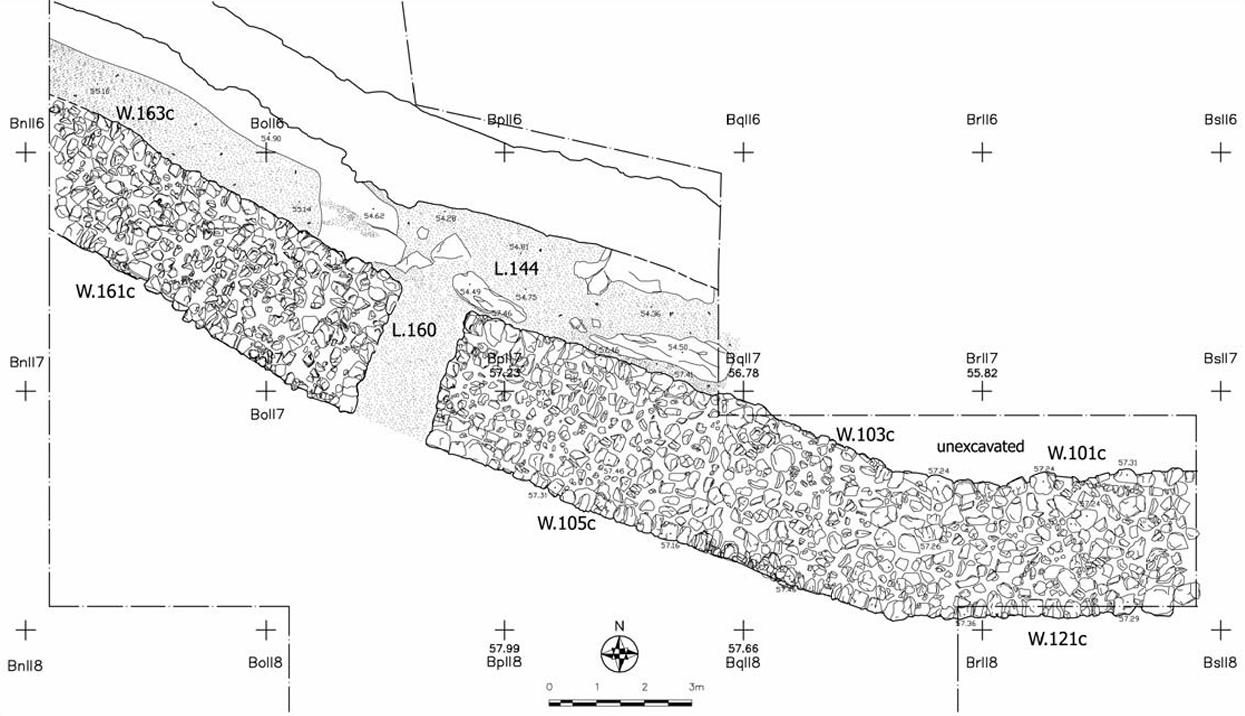

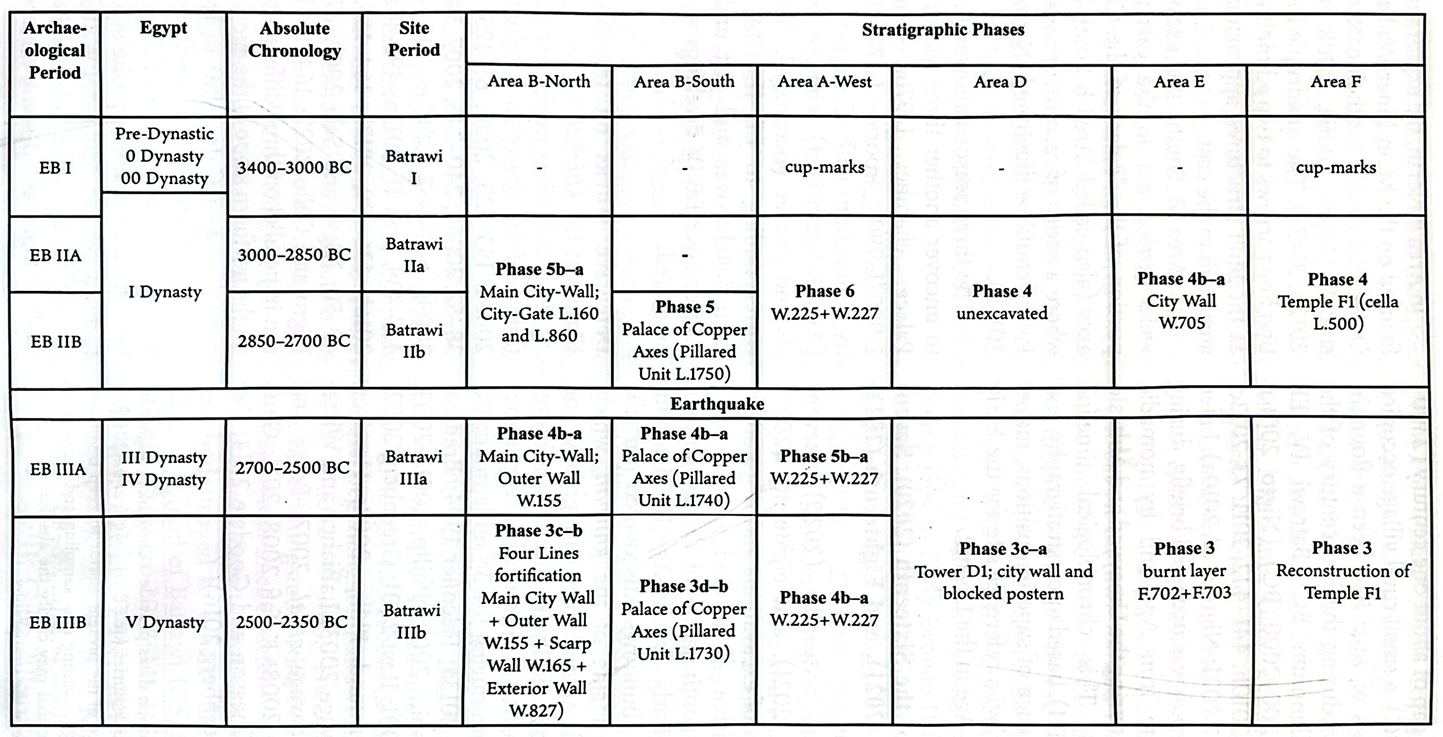

- from Nigro (2025)

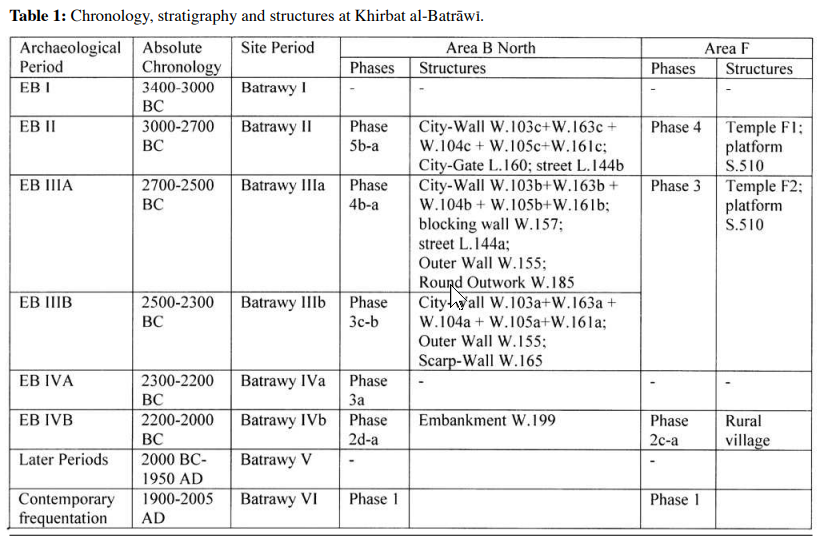

Table 1

Table 1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphic phases at Kirbat Al Batrawi

Nigro (2025)

Table 1

Table 1Architectural and stratigraphic phasing of Khirbat al-Batråwi

Nigro and Sala (2010)

Table 1

Table 1Chronology, stratigraphy and structures at Khirbat al-Batråwi

Nigro and Sala (2009)

- from Nigro (2008)

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphic phases of Khirbet al-Batrawy.

Nigro (2008)

- from Nigro (2008)

Table 3.1

Table 3.1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphy of Area B North.

Nigro (2008)

- from Nigro (2008)

Table 4.1

Table 4.1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphy of Area B South.

Nigro (2008)

- from Nigro (2025:521)

- from Nigro (2025:522-523)

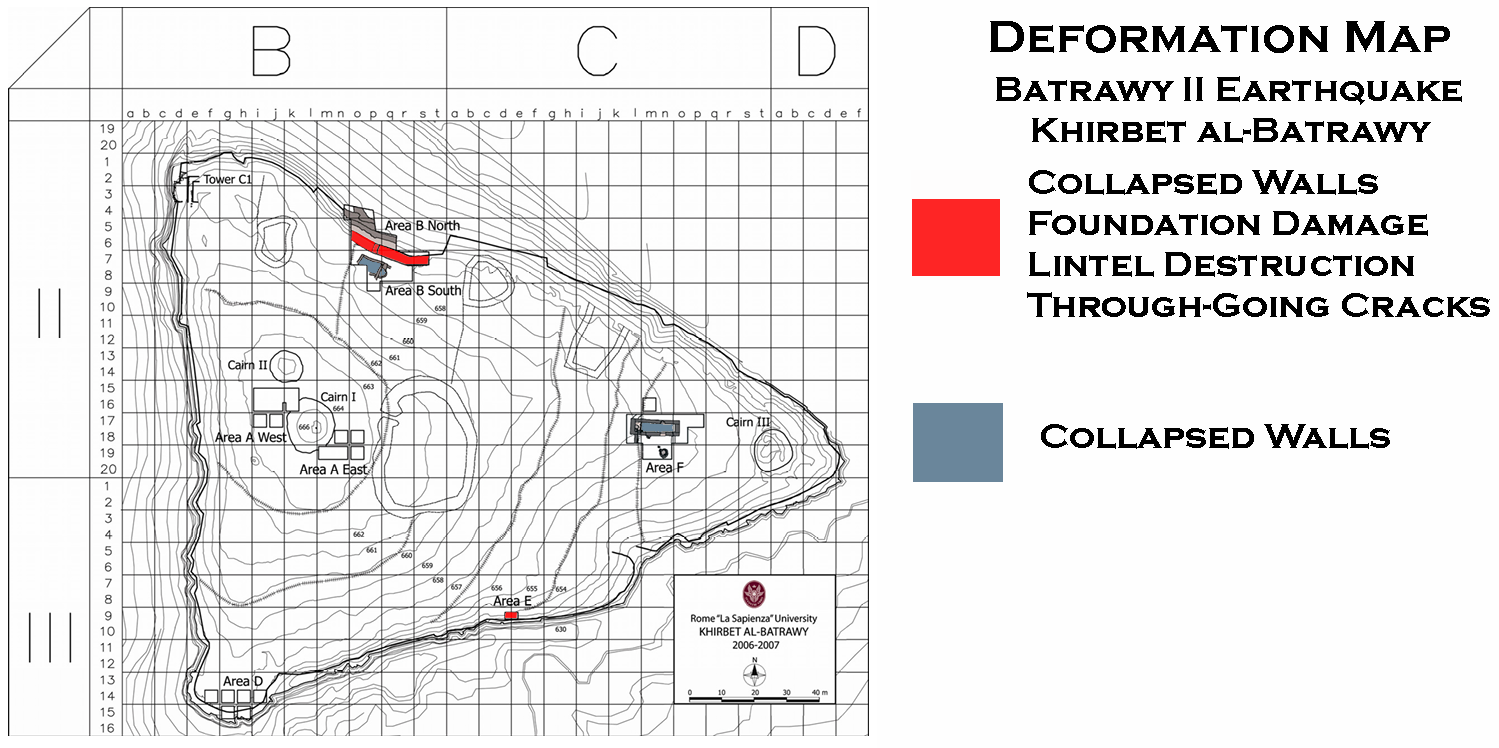

This early city suffered a major destruction caused by a tremendous earthquake around 2700 BCE, which left cracks in the earliest MIW. The city was promptly rebuilt with a monumental layout during Early Bronze IIIA (Batrawi IIIa, EB IIIA, 2700–2500 BCE) (Nigro 2007: 349–358, fig. 8; 2008: 87–90, 245–268, fig. 3.37; 2009: 666–667; 2010a: 38; 2010b: 437; 2017b; Gallo 2014: 150, fig. 4).

This flourishing phase, which included the so-called “Palace of the Copper Axes,” was again rebuilt around 2500 BCE at the beginning of Batrawi IIIb (EB IIIB, 2500–2300 BCE). The final and most prosperous city—fortified with up to four lines of defensive walls along the northern slope—was destroyed by a fierce conflagration around 2300 BCE (end of Batrawi IIIb, EB IIIB, 2300 BCE) (Nigro 2008: 141–142; 2012b: 163–165; 2010a: 71–110; 2012d: 228; 2014d: 77–78; 2017b: 164; Nigro and Sala 2011: 88–89; 2012: 49–50; Nigro et al. 2010a; 2011; Gallo 2014: 158–160).

After a hiatus of roughly a century (2300–2200 BCE), a small rural village occupied the ruins during the final century of the 3rd millennium BCE (Batrawi IV, EB IVB, 2200–2000 BCE) (Nigro 2006a: 37–40; 2010b: 441–442; 2011: 73; 2012c: 616–617; 2021; Nigro et al. 2010a). Later, the khirbah was briefly re-occupied in the Late Iron Age and again by nomadic groups during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. This chronological sequence, supported by stratigraphy and the absence of superimposed layers, establishes Khirbat al-Batrawi as a key reference site for the Early Bronze Age in the Levant1.

1. Radiocarbon dates provide a chronology higher by about two centuries for EB III (Nigro et al. 2019). It is a choice of the present author to keep traditional chronology, awaiting new sampling and excavations at the site that may clarify the absolute chronology anchorage of the stratigraphy.

- from Nigro (2025:523-526)

During the three seasons 2020-2022 a 15 m long stretch of the fortification was brought to light in this easternmost stretch (FIG. 3). The MIW turns slightly northwards 10.67 m from Gate L.160, and then it runs for another 16 m to the east. As the originally parallel Outer Wall does not turn, the latter gradually joins the outer face of the MIW. In the last 7m so far exposed, the two walls run adjoined, and the Outer Wall has a walkway on top, the clayish floor of which was in some spots still preserved (FIG. 4). This may explain double/flanked city-walls known from several fortified centers of Early Bronze II-III Southern Levant (e.g., Khirbat Az Zayraqun, Tall Tiannak (Douglas 2007: 30, figs. 4, 14-18, 26, plans 6-9, phase 2; Lapp 1964: 7-12; Nigro 2008: 93-94, 2012b: 41).

Under a thick layer of collapsed stones (F.1552) and limestone squared blocks, sometimes cut through by pits, the MIW was preserved at a height of about 3 m, possibly because it was supported by the Outer Wall leaning against it. The lower foundation course of the Outer Wall was brought to light at the bottom of the structure, showing that the wall gently turns southwards to join with the Main Inner Wall (FIG. 4).

Ceramic finds, albeit scanty, have confirmed the already consolidated reconstruction of the development of the city of Al Batrawi fortifications: the Main Inner Wall was the first built defensive line and it was erected at the beginning of Early Bronze II (ca. 3000 BC); the Outer Wall was added to the former after a terrible earthquake had struck it and brought the superstructure made of bricks down at the beginning of EB IIIA (ca. 2700 BC). A further fortification structure ( Scarp Wall W.165) was added in Early Bronze IIIB (2500-2300 BC), partly incorporating a round outwork or tower (W.185) overlooking the entrance to the city built in EB IIIA (ca. 2700 BC) and fallen out of use2.

After the final destruction and the abandonment of the city, its ruins were regularized when a new group settled it in EB IVB (2200-2000 BC). The huge collapsed city-walls were transformed into a stone-revetted rampart and a series of dwellings arose on the hilltop. The new settlers were shepherds and agriculturalists (Nigro 2011: 73, 2012c: 616-617, 2021: 295-298; Nigro et al. 2010a). We do not know their necropolis—as for the former inhabitants of Al Batrawi, it has been suggested that the burial place of the EB II-III city elite was in a village to the west, where the funerary rites reserved to high rank people were performed (Nigro et al. 2010a; Nigro 2021: 299). dividuals were carried out (Nigro et al. 2010a; Nigro 2021: 299).

2 Such a round tower is comparable to a similar defensive structure at Khirbat Al Karak (Fortification C; Greenberg and Paz 2005: 94-96, figs. 1-2, 5-6; Greenberg et al. 2006: 249-267; Nigro and Gallo 2022: 167-169).

- from Nigro (2025:526-527)

During the 2021 season, the southern wall (W1289) of Courtyard L.1046 was further explored. It was a terrace wall, leaning against a step cut in the bedrock. Courtyard L.1046 was a rectangular open space which was the centre of the Eastern Pavilion of the palace, accessible through central corridor L.1050 with a rectangular hall on its northern side (L.430) (Nigro 2013b: 198-204, 2016b: 139-149, 2017b: 162-164, 2012b: 179-181). The floor of the court was made of a layer of yellowish beaten clayish marl and by the emerging bedrock and lasted in use for the whole life of the palace.

The eastern wall of the courtyard, W1187, was further explored in its southern extension, where a blocked door (L.992) was identified (with two yellowish bricks indicating the threshold on its eastern side: W1759), connecting Court L.1046 with Hall L.1750. W1187 was then interrupted and joined a curved structure (W969) abutting into the southeastern corner of L.1046, and encompassing a blind chamber (L.976), possibly hosting a wooden staircase or a light well. The small chamber (0.95 x 0.94 m) was delimited by the round wall (W969) to the north, and by wall W973 to the west, and wall W983 to the east.

In the 2022 season, the expansion of the dig eastwards allowed it to explore almost completely the southern half of the second row of rooms of the Eastern Pavilion. Here, courtyard L.936, with the two semi-circular installations, oven T.413 and silo S.931 (Nigro 2007: 353, 2009: 668-669, fig. 13, 2010b: 444, 2008: 158-159, figs. 4.53-4.57, 2012b: 175-176) opened towards a rectangular room (L.1750 in Phase 5, L.1740/L.990 in Phase 4, and L.1730 in Phase 3) with a double pillared entrance. In Phase 4, in the southwestern portion of the hall a rectangular (4.2 x 2.1 m) room (L.980) was built (FIG. 6). This room was built using the southern wall of the pavilion (W989) as the rear wall. Its eastern wall (W.1715) rested upon two previous structures: an original Phase 5 partition wall or bench (W1733) and a Phase 4 structure (W1719). Room L.980 had two flat bases inside to support wooden pillars for the ceilings (W9853 and W1757) and was connected to the upper floor of the palace in this courtyard (L.990/L.1740, L.1730). Another bench or a step made of two bricks (W.1751) was set against a substantial wall (W1735), with an adjoined oblique wall (W1739), leaning on bench W1733. In the eastern section of the dig, wall W1737 was uncovered, made of regularly cut stones and re-employed bricks, parallel to W1187 and attributed to Phase 4 (EB IIIA); it rested upon an earlier structure (W.1755) made of bricks and laying on floor L.936. This structure was the eastern limit of the unit (FIG. 7).

Two corresponding offsets protruded respectively from wall W1737 and W1187, framing a 7 m wide porch, with two pillars in the passage, set on 0.5 m long limestone slabs, and each placed at 1.5 m from the 0.5 m thick offset and at a distance of 3 m from one another (FIG. 8).

The excavation of the Pillared Unit L.1750 in the southeastern half of the Eastern Pavilion of the "Palace of the Copper Axes" provided a full stratigraphy of the palace, showing that while courtyards kept the same floor across phases, rooms were rebuilt by raising their pavements during at least three main stages of use (Batrawi IIb, IIIa, IIIb).

3. Slab W985 measured 0.39x0.41m and lay 1.40m north of wall W989. It was interpreted as a pillar base.

- from Nigro (2025:528)

- from Nigro (2025:528)

A peculiar find, retrieved in L.976, is a fragmentary rim of a hole-mouth jar made of a reddish-brown local fabric with an incised sign (FIG. 11), possibly depicting an animal (a bee or a catfish, fishes that in antiquity were living in the Az Zarqa" River)4.

4.

- from Nigro (2025:528-529)

4. The similarity with the catfish sign used to write part of Narmer's name (cfr. Umm al-Qaab, Abydos (Kayser and Dreyer 1982: 263, fig. 14-15, nr. 40); Zawiyet al-Aryan t. Z401 jar fr. (Dunham 1978: 26, Pl. XVIb 2/2-4; Kayser and Dreyer 1982: 263, fig. 14-15, nr. 37; Van den Brink 2001); Hierakonpolis jar fr. (Kayser and Dreyer 1982: 263, fig. 14-15, nr. 43), as exemplified by the one from Tall al Areini (Yeivin 1963: 207-208, fig.1-2; Kayser and Dreyer 1982: 263, fig. 14-15, nr. 41; Weinstein 1984: 64), cannot be proven because the hypothesized head of the catfish is broken. Animals such as snakes and scorpions were present in the imagery of pottery in the "Palace of the Copper Axes" (KB.11.B.1054/4 and KB.11.B.1054/1; Nigro 2013b: 201, 2016b: 143, fig.12-13, 2010a: 103, sherd 1054/79).

- from Nigro (2008:65)

- from Nigro (2008:75)

Table 3.1

Table 3.1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphy of Area B North.

Nigro (2008)

...

3.1.5. Phase 5: stratigraphy of Batrawy II fortification system

Phase 5 is basically constituted by the destruction layer (Activity 5a) marking the end of the Batrawy II city, and the original constructional phase (Activity 5b).

Activity 5a: destruction of Batrawy II city-gate and city-wall

A layer around 0.2-0.3 m thick preserved only in two spots in the excavated area, namely in square BoII5 (to the west) F.168 (fig. 3.16) and within the gate passage (F.172), including fragmentary grayish mud-bricks and small pebbles, illustrates the collapse and destruction of the city-gate and earliest city-wall of Batrawy II (fig. 3.17).

Activity 5b: construction of Batrawy II city-gate and city-wall

The earliest city-wall and city-gate L.160 were erected directly over the bedrock and included the two doorjambs (W.183 to the east, W.156 to the west), entrance step L.182, marking the passage into the gate, floor L.186 into the passage, and street L.144b outside the gate. All features were linked each other.

- from Nigro (2008:77-87)

3.2.1. The earliest city-wall and city-gate (Period Batrawy II, Early Bronze II)

The earliest defence of Batrawy (fig. 3.19) was a solid wall 2.9-3.2 m wide, consisting of a lower foundation made of huge limestone blocks and boulders (some exceeding 1.5 m in length by 1.0 in width) on the northern outer face (W.103c+W.163c; figs. 3.20-3-21), and of big blocks (0.5 x 0. 6 m) on the southern inner curtain (W.105c+W.161c; fig. 3.22). The inner core of the wall (W.104c) was made by medium size undressed stones laid in regular layers with pebbles, limestone chops and mud mortar. The outer (W.103c+W.163c) and inner (W.105c+W.161c) walls were carefully set into the bedrock16, and the outer wall exhibited a battering foot in order to make firmer the whole structure17.

This imposing stone foundation was 2.3 m high around the gate and 2 m in the rest of the area; it supported a mud-brick superstructure up to 4 m high18 with battering sides, reaching on top a hypothetical width of 2.2 m, presumably with a wooden coronation and a continuous parapet slightly protruding from the façade (fig. 3.23). The city-wall was built in separated stretches of 6-8 m length in order to prevent dangerous effects of earthquakes19, a technique also attested to in other Early Bronze urban sites in Palestine and Jordan20.

Street L.144 (Period Batrawy II, Early Bronze II)

A street (L.144b) run along the city-wall on its outer side (figs. 3.24 3.25)21, paved with a layer of a gritty chalk plastering the bedrock and regularizing its surface (at some spots also stone fillings were used to make the street floor more regular). The collapse layer lying over the street, F.168, preserved only in square BoII5 (§ 3.1.4.), included EB II sherds (pl. XXI), a stone blade22, and various fragments of greyish mud-bricks.

The city-gate of Period Batrawy II (Early Bronze II)

In spite of the monumentality of the city-wall, the EB II gate was a simple opening, 1.6 m wide, since the town was approachable only by pedestrians and equids (onagers or donkeys) through the street (L.144b) which flanked the wall (figs. 3.26-3-28). A 0.27 m step (B.182) marked the entrance (figs. 3.29-3.30)23 to the passage, paved with a plastered floor (L.186), and flanked by reinforced door-jambs made of bigger and carefully intermingled blocks, which supported a monolithic capstone (2.4 x 0.7 x 0.35 m) on the outer side and a wooden beam on the inside (as it is indicated by burnt traces on the faces of the stones in between the beams were inserted). At least four wooden beams were presumably employed in the ceilings of the gate passage and supported the brick superstructure (fig. 3.56). The eastern jamb (W.183) was made, on its outer side, by a series of alternately superimposed cubic and rectangular limestone blocks (figs. 3.31-3.32); the western jamb (W.156) was reinforced by a large slab on its fourth course of stones, linked to a huge bock visible on the northern façade of the main wall (figs. 3.33-3.34, 3.36). Such a strengthening device was set in the wall just above a protruding buttress (W.187), preserved only at the lowest course of stones over the bedrock (fig. 3.35), perhaps to be connected with a passage through the street running along the city-wall (L.144b). In spite of its apparently simple layout, the EB II gate at Batrawy accomplished mainly defensive purposes, since due to its dimensions (the passageway was a corridor 1.6 m wide and 3.2 m long), it was easy to be looked out and to be locked in case of enemy attack; it was, anyhow, the main access to the town, as its location on the city perimeter and the organization of spaces inside and outside it testifies to.

Nonetheless, the plan of gate L.160 finds several comparison in contemporary EB II defensive architecture of the region, such as at Khirbet Kerak24, Tell el-Far‘ah North25, et-Tell/‘Ai26, Arad27, Khirbet ez-Zeraqon28, and, later on in EB III, also at Bab edh-Dhra‘29.

There is no evidence for the presence of towers adjoined to this early gate, even though the area was completely reconstructed when the gate was blocked and an outer wall (W.155) was added to the defense at the beginning of the Early Bronze IIIA (see below § 3.2.2.).

Two sharp earthquake cracks on the eastern jamb (fig. 3.37) testify to the destruction of the lintels and possibly of the capstone of the passageway, which presumably caused a general collapse, so that the gate went out of use at the end of the Early Bronze II30.

3.2.2. The double city-wall of Period Batrawy IIIa (Early Bronze IIIA)

After the destruction which caused the partial collapse of the gate and brought to a sudden end the EB II city, the defensive system in Area B North, at the most sensitive and exposed side of the town, underwent a general reconstruction. The gate was blocked by a solid wall made31 with big stones (W.157; figs. 3.38-3-40)32, and the superstructure of the main city-wall (W.103b+163b + W.104b+ W.105b+W.161b) was rebuilt em ploying medium size stones up to a height of around 4.0-5.0 m; only the upper section of the structure was built up with reddish mud-bricks up to 8 m. The original stretches in which the main wall was subdivided33 were tied up one to the other (on its outer face this indicates in several spots the height from which the wall was reconstructed).

16 Usually the elevation of the inner foot of the main city-wall is around 0.5-1 m

higher than that of the outer one.

17 Nigro ed. 2006, 175-176, fig. 4.32.

18 Actually, there is no information on the dimension of this brick superstructure.

Fragments of greyish mud-bricks were retrieved in the destruction layers of Period

Batrawy II, however even the dimensions of the bricks is uncertain (0.6 x 0.4 x

0.16 m), while the height of the superstructure has been calculated according to

the presumed height of the later EB III city-wall, suggested by a flight of steps of a

staircase discovered inside wall W.105b+W.161b (staircase W.181, § 3.2.2.).

19 Nigro ed. 2006, 176-177, note 26.

20 See below note 27.

21 This street was already partially identified in the first season (Nigro 2006a, 245,

fig. 26; Nigro ed. 2006, 191, figs. 4.53-4.54).

22 KB.06.B.74 (pl. XXI).

23 The elevation outside the gate is 54.49 m, while the floor inside the gate was

55.01 m.

24 The South-East Gate in Wall A (2.5 m wide; Greenberg - Paz 2005, 84, 86-89,

fig. 8, 10-14; Greenberg et al. 2006, 239-244, plans 6.2, 6.4).

25 De Vaux 1962, 221-234, pls. XIX-XXI.

26 The Citadel Gate at Site A (around 1 m wide and 4.5 m long; Callaway 1980,

63-65, figs. 38, 41); the Postern Gate (around 1 m wide; Callaway 1980, 72-73,

figs. 48-49, 51) and the Lower City Gate (around 1 m wide; Callaway 1980, 114

115, figs. 74-75) at Site L.

27 The Western Gate in Area T (2.50-2.70 m wide), the Gate in Area N (2.10 m

wide), and the Postern Gate in Area K (0.80 m wide): Amiran - Ilan 1996, 20-22,

pls. 68-70, 78, 85-86, 90-93.

28 The City-Gate in the Lower City fortifications (around 2.0-2.5 m wide; Douglas

2007, 9, figs. 3, 6-12, pls. 1-5; phase 4g-a; EB II). Just 7 m north-west of the

main city-gate a postern 0.80 m wide (sortie-postern) was opened across the city

wall W1 (Douglas 2007, 10). According to excavators, it was closed after a little

while already during the Early Bronze II (Douglas 2007, 14; phase 4d).

29 The EB III West Gate in Fields IV and XIII, also blocked during the Early Bronze

III (Rast - Schaub 2003, 272-280, fig. 10.12). A possible EB III postern (around

1.50 m wide) at Tell Ta‘annek, detected on the western side of the site (Lapp

1964, 12, fig.4), exhibited instead a bent-axis plan.

30 Nigro 2007a, 352; in press a, § 6. This was the case of other centres of the

North-Central Jordan Valley: Pella/Tell el-Husn, Tell Abu Kharaz and Tell es

Sa‛idiyeh, which were apparently destroyed in the same period and by a similar

agent (Bourke 2000, 233-235). Such a conflagration apparently caused by an

earthquake is attested to also at Megiddo (Finkelstein, Ussishkin and Peersmann

2006, 49-50), ‘Ai (Callaway 1980, 147; 1993, 42), Jericho/Tell es-Sultan (Kenyon

1957, 175-176, pl. 37a; 1981, 373, pls. 200-201, 343a; Nigro 2006c, 359-361,

372-373). Also at Khirbet ez-Zeraqon, phase 3 (EB II) ends in a fierce conflagration

(Douglas 2007, 27-28), though it is not surely ascribable to an earthquake.

31 EB II city-gates at ‘Ai were partly blocked already in the late Early Bronze II

(the Citadel Gate and the Postern Gate; Callaway 1980, 113-115), partly at the

beginning of the Early Bronze III (the Lower City Gate; Callaway 1980, 152-154).

Also at Khirbet Kerak, EB II south-east gate in Wall A was possibly blocked at the

beginning of the Early Bronze III (Greenberg - Paz 2005, 89, figs. 13-14;

Greenberg et al. 2006, 245, fig. 6.18, plan 6.5). The same happened in the Early

Bronze III at the City-Gate of the Lower City at Khirbet ez-Zeraqon (Douglas 2007,

35-38, figs. 5, 19-20, plans 10-11; phase 1, Early Bronze IIIB).

32 Only a few pottery sherds were retrieved in wall W.157 dating back from EB

II/early EB IIIA (pl. XXI).

33 Nigro ed. 2006, 176-177.

- from Nigro (2008:245)

In Area E the main city-wall was cleaned for a length of around 10 m, and the sounding was opened just aside a small ravine (fig. 6.2), which cut through it in correspondence of a joint between two separated sections of the defensive structure2, at a change of its orientation (fig. 6.3).

A major achievement of this sounding was the confirmation that the city wall preserved here dates back from the Early Bronze II (2900-2700 BC)e3, since the later EB III reconstructions collapsed and were almost completely obliterated by erosion, and that the fortified town of Batrawy was founded at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC.

1 Nigro 2007a, 357-358, figs. 1, 17.

2 The Batrawy II city-wall was built in separated juxtaposed stretches (each

around 8 m long), as it was also evident in Area B North (in trench BrII7 + BsII7

excavated in 2005), where a junction between two of such sectors (named wall

W.103c to the west and wall W.101c to the east) was visible on the northern outer

face of the main city-wall (Nigro 2006a, 243; Nigro ed. 2006, 176-177, note 26,

fig. 4.35, pl. IV). For a detailed analysis of this well-known building technique from

EB II-III defensive systems in Southern Levant see Area B North, §§ 3.2.1.-3.2.3.;

Nigro 2006c, 370-371; 2006e, 9; 2007a, 352, 357; in press, §§ 4.2.-4.3.

3 Nigro 2007a, fig. 18.

- from Nigro (2008:247)

Strata were all eroded according to the slope of the khirbet and they illustrated four main phases (tab. 6.1; fig. 6.4), from the topmost shallowest layer of humus to the earliest strata related to the destruction of Batrawy II city-wall, founded directly upon the bedrock (Phase 4). Structures and finds from destruction layers of Phase 4 will be thoroughly described in § 6.2.

Table 6.1

Table 6.1Archaeological periodization and stratigraphy of Area E

Nigro (2008)

...

6.1.4. Phase 4: stratigraphy of Batrawy II fortification system

Phase 4 illustrates the erection (Activity 4b), first utilization and sudden end, testified to by a thick collapse layer in the fillings inside the town (Activity 4a), of Batrawy II fortification system during the Early Bronze II.

Activity 4a: destruction of Batrawy II fortification system

Deposits of Period Batrawy II have been clearly identified in the sounding inside the southern line of the main Batrawy city-wall (W.705), where a thick layer of destruction and collapse was accumulated on a floor lying directly over the bedrock. Here, an upper stratum (F.704) of grey clayish sandy soil, 20-25 cm high, with ashy lenses, charcoals and small limestone chops probably from the Batrawy II city-wall superstructure, as well as scattered animal bones (samples KB.06.FR.106 and KB.06.FR.123) and pottery sherds (pl. LIII), covered a greyish layer (F.706), 20 cm thick, basically composed of compacted charcoals, ash and crushed greyish mud bricks, with numerous limestone grits, chops and mud mortar from the EB II city-wall collapsed superstructure (§ 6.2.), as well as a few pottery sherds (pl. LIV). Both these layers sloped from north to south and from west to east according to the natural slope of the bedrock.

Activity 4b: erection of Batrawy II fortification system

Activity 4b represents the erection of Batrawy II city-wall, the earliest phase of the Batrawy fortification system, similarly detected in Area B North (§ 3.1.4.). It is illustrated by the inner face of city-wall W.705 and the earliest floor exposed inside the town (L.710), lying directly upon the bedrock, in trench CdIII9 + CeIII9 (§ 6.2.), and by the inner face of the westerner juxtaposed stretch of city-wall W.707, further to the west.

- from Nigro (2008:251-255)

The defensive work, consisting of a single wall running on the very edge of the cliff, was strongly eroded on the outer side, where its outer face was preserved only for the lower courses of limestone boulders directly set into the bedrock (fig. 6.11). Conversely, the inner face of the wall was preserved on four superimposed courses of unworked stones, tied up with mortar and small limestone chops (figs. 6.12-6-13).

As well documented in the EB II main city-wall in Area B North (§ 3.2.1.), the Batrawy II city-wall was built in separated juxtaposed stretches (each around 6-8 m long)12, according to a well-known technique attested to in many Early Bronze fortified sites in Palestine and Transjordan, in order to prevent dangerous effects of earthquakes13.

Inside city-wall W.705, where the sounding was opened, a well refined floor (L.710) of limestone marl and small pebbles, lying directly over the bedrock (fig. 6.14), was uncovered after the removal of a thick heavy destruction layer (F.704, F.706). From the latter layer, scattered fragments of EB II common wares were retrieved14, as well as some specimens of EB II typical specialized productions, such as Red Burnished15 and Red Polished16 vessels (pls. LIII-LIV). A flint blade17 and a Canaanean blade18 were also retrieved in layer F.706.

A typical feature of this phase was the presence of fragmentary light greyish mud-bricks in the layers of collapse, belonged to the superstructure of the EB II city-wall. The greyish mud-bricks of the city-wall superstructure were split over the stone foundations and left a thick stratum of greyish dump all around the defences, especially visible on the southern inner side of the khirbet.

The Batrawy II fortifications in Area E show that a violent earthquake brought to a sudden end the earliest city. Traces of such a dramatic event were detected both on the northern and southern city-wall, in Areas B North (§ 3.2.1.) and E. It provoked almost the full collapse of the mud brick superstructure and seriously damaged the 2 m high stone foundations of the Batrawy II city-wall, as it is clearly documented in the cracks and inner collapses detected in the EB II city-wall and city-gate in Area B North (§§ 3.1.4., 3.2.1.).

12 In trench BrII7+BsII7 excavated in 2005 a junction between two of such sectors

(named wall W.103c to the west and wall W.101c to the east) was visible on the

northern outer face of the main city-wall (Nigro ed. 2006, 176, fig. 4.35, pl. IV).

13 Nigro ed. 2006, 176-177, in particular note 26.

14 Two fragments of storage jars with Grain Wash decoration from layer F.706 can

be noticed (KB.06.E.706/7, KB.06.E.706/8; pl. LIV).

15 A platter (KB.06.E.704/1) and a bowl (KB.06.E.704/6) from layer F.704 (pl.

LIII), and three platters (KB.06.E.706/1, KB.06.E.706/2, KB.06.E.706/3) from layer

F.706 (pl. LIV).

16 Three jugs (KB.06.E.704/7, KB.06.E.704/14, KB.06.E.704/15) from layer F.704

(pl. LIII), and a jar (KB.06.E.706/5) from layer F.706 (pl. LIV).

17 KB.06.E.86 (pl. LIV).

18 KB.06.E.102 (pl. LIV).

... During the fourth season5, excavation and restoration was focused on three areas (Area B North, Area B South and Area F), respectively located in the middle of the northern side of the tall, both outside and inside the main city wall, and on the easternmost terrace of the site (Fig. 2; Nigro 2008b).

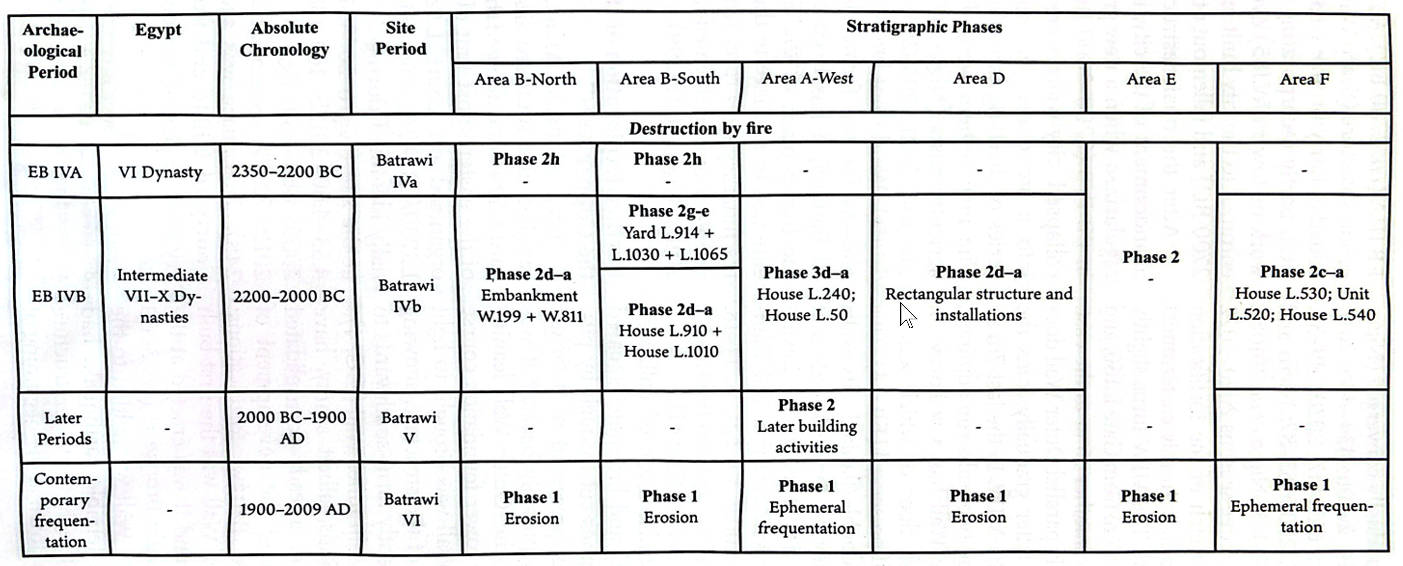

5. In previous seasons (Nigro 2006a, 2006b, 2006c, 2007a, 2007b, 2008a, 2008b; Nigro ed. 2006, 2008), the main chronological, topographical and architectural features of the site were established (Nigro 2006a: 233-236, 2007a: 346-347, tab. 1; Nigro ed. 2006: 9-36, ig. 1.2, 2008: 7-8), and ive areas opened, respectively on the Acropolis (Area A: Nigro 2006a: 236-240, 2007a: 347- 349; Nigro ed. 2006: 63-102, plan II, 2008: 9-63), the northern slope (Areas B North and South: Nigro 2006a: 240-246, 2007a: 349-354; Nigro ed. 2006: 153-196, plans III-IV, 2008: 65-240, plans I-II), at the northwestern and south-western corners (respectively Area C: Nigro ed. 2006: 25-27, igs. 1.27-1.31 and Area D: Nigro 2007a: 355-357; Nigro ed. 2006: 32-33, igs. 1.38-1.41; 2008: 241-244), on the southern side (Area E: Nigro 2007a: 357-358; Nigro ed. 2008: 245-268) and on the easternmost terrace of the Khirbat (Area F: Nigro 2007a: 358-359; Nigro ed. 2006: 22, ig. 1.25, 2008: 269-316, plans III-IV).

Excavations in Area B North provided a detailed insight into the occupational and architectural sequence, not only of the fortiication system, but also of the city as a whole9:

- Phase 1: Topsoil, representing natural erosion and dust accumulation following the final abandonment of the site around 2000 BC.

- Phase 2: Consisting of stone embankment W.199, which stabilised the collapsed defensive structures of the Early Bronze IIIB city in order to support and protect the Early Bronze IVB dwellings erected within the main city wall in Area B South.

-

Phase 3: The most recent, Early Bronze IIIB urban phase which includes:

- Event 3a: the abandonment and progressive collapse of destroyed defensive structures.

- Event 3b: violent destruction, with burned layers of dark grey ash, charcoal and reddish-yellow mudbrick fragments, which marks the end of the third millennium BC city; excavated between the main city wall and outer wall W.155, between outer wall W.155 and scarp wall W.165, and to the north of the latter.

- Event 3c: the final rebuild of the Batrawy IIIb fortification system, in which the main city wall and outer wall W.155 were retained from the previous phase, with the addition of new scarp wall W.165.

-

Phase 4: The Early Bronze IIIA reconstruction of the defensive system, which includes:

- Event 4a: again represented by a violent destruction layer excavated between the main city wall and outer wall W.155.

- Event 4b: blocking of the collapsed Phase 5 city gate with wall W.157 and the erection of outer wall W.155 with associated curvilinear outwork W.185.

-

Phase 5: Earliest phase of the city, including:

- Event 5a: collapse of the main city wall and gate, attested to by a thick layer of compact yellowish-grey soil with limestone chippings, and fragments of greyish mudbricks found outside the main city wall on the plastered floor of street L.144b, which lies directly over bedrock.

- Event 5b: erection of the main city wall and gate, marking the foundation of the city.

9. For the stratigraphy of Area B North up to and including the third, 2007 season see Nigro ed. 2008: 66-76.

In Area B North, on the northern slope of the hill, the initial urban fortiication was a triple line of defence with several associated outworks, demonstrating that the city reached its most heavily defended state towards the end of the Batrawy III period (Nigro 2007a: 351-352; Nigro ed. 2008: 100-102, plan III). A further structure, scarp wall W.165, was added to the outer side of the original main city wall, now reinforced by outer wall W.155. Scarp wall W.165 was characterized by the placement of large, irregular stones on a foundation of medium-sized stones. It had already been exposed to the west, in square BoII4, during 2006. In 2008, it was followed eastwards through three more squares, BpII5, BqII5 and BrII5, where its five courses of stone attained a height of 1.2m, and westwards into BnII4, where its eleven courses attained 1.8m. Between scarp wall W.165 and outer wall W.155, was a rubble fill10 which was fully excavated in BnII4 (Fig. 5). Scarp wall W.165 strengthened the outer line of fortiication and incorporated dismantled EB IIIA curvilinear outwork W.185 (see below).

The EB IIIB triple fortiication line underwent a violent destruction. Several burned strata of ash and charcoal were identiied:

F.802 in BnII5 (Fig. 6) and F.194 in BrII6, BrII7 and in the baulk between squares BqII6 and BrII6, that is to say between the main city wall and the outer wall; F.807 between the outer wall and scarp wall; F.804 on the outer slope, north of the scarp wall.

10. This rubble fill was designated F.808 to the west, in BnII4, and F.193 to the east, in BpII5 and BqII5.

At the beginning of Early Bronze IIIA, after the dramatic destruction of the EB II city in a violent earthquake (Nigro ed. 2008: 87, 255), the main city wall was reconstructed by blocking the collapsed city gate and rebuilding the superstructure of the wall, as clearly illustrated during the 2008 season by excavations in square BnII5 and in the baulk between squares BqII6 and BrII6. This baulk was at the intersection of two separate stretches of the original city wall, which were incorporated into the EB IIIA reconstruction.

In addition to this reconstruction of the main city wall, an outer wall, W.155, was constructed using boulders on its outer face and large stones on its inner face. The stretch excavated so far (Fig. 7), runs parallel to and 1.7m in front of the main city wall.

In square BnII5, the space between the main city wall and the outer wall was filled with a destruction layer of ash and charcoal, designated F.805 (Figs. 8 and 9). In squares BrII6 and BrII7, a further section of outer wall W.155 was exposed in 2008, which showed how a fill of limestone pebbles and chippings, F.803, had been deliberately deposited in order to regularize a step in the bedrock (Fig. 10). Just above it was a fill of loose brown soil and rubble, F.196.

A major curvilinear outwork, W.185, abutted the outer wall, strengthening and protecting the north side of the city, the direction from which it was most easily approached.

During 2008, archaeological activities in Area F were focused on completing the excavation of the Early Bronze II - III broad room temple discovered in 2006, roughly in the middle of Terrace V (Nigro 2007a: 359). This monumental structure, though badly eroded and truncated at its north-eastern corner by later Early Bronze IVB dwellings, could still be understood in terms of its two major constructive phases, attributed to Early Bronze II and III respectively (Fig. 15)11. Three soundings dug within the temple cella and complete excavation of its western side clariied the transformation this religious building underwent when it was reconstructed at the beginning of Early Bronze III, around 2700 BC.

11. For a comprehensive illustration of stratigraphy, Nigro ed. 2008: 269-275.

The original temple was erected directly over the bedrock, by filling in a shallow depression under the approximate centre of the building with virgin soil and small rock fragments (Nigro ed. 2008: 276-282, plan III). The presence of this depression weakened the central part of the structure, which in fact collapsed during the tremendous earthquake, which brought about the end of the Early Bronze II city.

The original walls of the temple were preserved along its southern, main façade (W.563E and W.563W) and its western (W.586) and northern (W.521) sides. The eastern wall was completely truncated by an Early Bronze IVB domestic building, which obliterated all previous structures. Only the south-eastern corner of the cella was preserved, but this allowed us to reconstruct the eastern wall (W.561) of the temple. The width of these walls varies from 1.0 to 1.2m, being wider on the western side where the temple abuts the bedrock step between terraces IV and V. The rear wall of the temple was excavated all the way to its western end, which led to the discovery of a curvilinear structure (W.587) connected with the north-western corner of the building. This may represent a boundary wall, similar to the one known from the Early Bronze II temple at at-Tall / ‘Ayy (Sala 2008b: 135-140, Fig. 40).

The cella itself was a broad room measuring 2.7m in width and 12.5m in length, with the entrance (L.592) two thirds of the way along its length. The entrance was in the form of a passage 1.4m wide. Four stone bases were aligned along the main axis of the cella, as supports for the wooden pillars, which would have held up the roof. Facing the entrance, which opened out on to a forecourt, and in the rear wall of the temple was a niche (L.562), 1.3m wide, 0.8m deep and with an internal bench 0.2m high. A small slab, with two circular depressions, at the northwest corner of the bench suggests that the niche was the cult focus of the temple.

In the forecourt, facing the entrance, was a circular altar (S.510) with a central slab with a small cup mark in the middle, and a light of three steps made of stone slabs by which to approach the altar from east. About 1m west of the altar, some stones set vertically into the ground (S.503) probably served as the base for a betyl (Fig. 16; Nigro ed. 2008: 283-284).

At the end of Early Bronze II, the earthquake, which destroyed the city of al-Batrawi badly, damaged the temple in Area F. The collapse of the central part of the façade led to the reconstruction of the temple entrance at the beginning of Early Bronze III (Fig. 17; Nigro ed. 2008: 285-290, plan IV). The new front wall was wider and more carefully built than its predecessor. The reconstructed part of the wall (W.505) was offset from the previous line by about 0.2m, and the entrance (L.550) included a small step 0.1m high. The rear wall was partly rebuilt and the niche facing the entrance closed off. The ceiling of the cella consisted of wooden beams spanning its entire width, as the pillar bases of the previous phase had been buried under the new floor of the room. The cult focus was shifted to the western side of the cella, which was reoriented (Fig. 18). A platform (B.585) 0.2m high was provided with a new style of raised niche (L.580), lanked by two vertical slabs and located in the middle of the western side. Against the southern wall of the cella was a stone-lined basin, delineated by stones set vertically into the platform, paved with lagstones and ending in a large slab. In front of the niche and its two antae, two round bases may indicate the location of two betyls (Fig. 19). A bench was placed against the northern side of the cella.

The transformation of this structure from a classic broad room temple into a bent axis cult place, where the religious symbols were grouped at the end of the short side to the left of the entrance, perhaps reflects the same gradual transformation of the deeply rooted tradition of southern Levantine religious architecture attested to at the contemporary sanctuary of Båb adh-Dhrå‘12.

12. Rast - Schaub 2003: 157-166, 321-335. For a general appraisal on the Early Bronze Age sacred architecture in the Southern Levant see Sala 2008b.

Nigro (2008:251–255)

reports that the Batrawy II fortifications show that a violent earthquake brought to a sudden end the earliest city

.

Archaeoseismic evidence was uncovered along both the northern and southern city walls—in Areas B North and E.

The earthquake provoked almost the full collapse of the mudbrick superstructure and seriously damaged the 2 m high

stone foundations of the Batrawy II city-wall,

as clearly documented by the cracks and inner collapses

detected in the EB II city-wall and city-gate in Area B North.

Nigro and Sala (2009:377) reported that the Early Bronze II Broad Room Temple F1 collapsed during the same earthquake in a collapse

that may have been exacerbated by poor construction practices. The original temple was erected directly over the bedrock,

by filling in a shallow depression under the approximate centre of the building with virgin soil and small rock fragments

(Nigro ed. 2008: 276–282, plan III).

Nigro and Sala (2009:377) further noted that the presence of this depression weakened the central part of the structure,

which in fact collapsed during the tremendous Batrāwī II EB II earthquake

.

Nigro (2008:87 n. 30)

noted that centres of the North-Central Jordan Valley

such as Pella/Tell el-Husn, Tell Abu Kharaz and Tell es Sa‛idiyeh [...]

were apparently destroyed in the same period and by a similar agent (Bourke 2000, 233–235)

.

Nigro (2008:87 n. 30)

also pointed to similar destruction at:

- Megiddo –

Such a conflagration apparently caused by an earthquake is attested to also at Megiddo (Finkelstein, Ussishkin and Peersmann 2006, 49–50)

- ‘Ai (Callaway 1980, 147; 1993, 42)

- Jericho/Tell es-Sultan (Kenyon 1957, 175–176, pl. 37a; 1981, 373, pls. 200–201, 343a; Nigro 2006c, 359–361, 372–373)

- Khirbet ez-Zeraqon –

phase 3 (EB II) ends in a fierce conflagration (Douglas 2007, 27–28), though it is not surely ascribable to an earthquake

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Area B North (north city-wall)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

Figure 3.37

Figure 3.37Earthquake cracks visible on the eastern jamb (W.156) of city gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.38

Figure 3.38City-gate L.160 after the blockage (W.157) at the beginning of the Early Bronze IIIA, from north. Nigro (2008) |

|

|

Area B North (north city-wall)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

Figure 3.24

Figure 3.24Street L.144b along the outer side W.103c+W.163c of Batrawy II city-wall, from west. Nigro (2008) |

|

|

Area E (south city-wall)

Figure 6.10

Figure 6.10Plan of Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

Area F - Early Bronze IIB

Broad Room Temple F1

Figure 15

Figure 15General view of the EB II - III broad room temple and round platform S.510 in Area F, from east-southeast. Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 16

Figure 16Reconstruction of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II) Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

Eastern Pavillion in Area B South also known as the Palace of the Copper Axes (Pillared Unit L.1750)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 1.2 from Nigro (2008)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 1.2 from from Nigro (2008)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Area B North (north city-wall)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

Figure 3.37

Figure 3.37Earthquake cracks visible on the eastern jamb (W.156) of city gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.38

Figure 3.38City-gate L.160 after the blockage (W.157) at the beginning of the Early Bronze IIIA, from north. Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

Area B North (north city-wall)

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19Plan of EB II city-wall W.103c+163c + W.104c+ W.105c+W.161c and city-gate L.160. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

Figure 3.24

Figure 3.24Street L.144b along the outer side W.103c+W.163c of Batrawy II city-wall, from west. Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

Area E (south city-wall)

Figure 6.10

Figure 6.10Plan of Batrawy II (EB II) city-wall and related floor inside the city. Nigro (2008)

Figure 3.23

Figure 3.23Schematic reconstruction of a stretch of Batrawy II city-wall. Nigro (2008)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

|

Area F - Early Bronze IIB

Broad Room Temple F1

Figure 15

Figure 15General view of the EB II - III broad room temple and round platform S.510 in Area F, from east-southeast. Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 16

Figure 16Reconstruction of Temple F1 with its forecourt (Phase 4, Early Bronze II) Nigro and Sala (2009)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

|

Eastern Pavillion in Area B South also known as the Palace of the Copper Axes (Pillared Unit L.1750)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Topographical plan of Khirbet al-Batrawy (2006-2007). Nigro (2008) |

|

|

|

Nigro, L. (2006) Preliminary Report of the First Season of Excavations of Rome “La Sapienza” Univesity at Khirbet al-Batrawy (Upper Wadi az-Zarqa, Jordan)

in J.M. Córdoba et al. (edd.), Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (5-8 April 2006), Madrid 2008, Volume II, pp. 663-682.

Nigro, L. and Sala, M. (2009) Preliminary Report on the Fourth Season of Excavations by "La Sapienza" University of Rome at Khirbat al-Batrāwī in Upper Wādī az-Zarqā’, 2008

, ADAJ 53

Nigro, L. and Sala, M. (2010) Preliminary Report on the Fifth Season (2009) of Excavations at Khirbat al-Batrāwī (Upper Wādī az-Zarqā’) by the University of Rome “La Sapienza"

, ADAJ 54

Nigro, L. and Sala, M. (2011) Preliminary Report on the Sixth Season (2010) of Excavations by "La Sapienza" University of Rome at Khirbat al-Batrāwī (Upper Wādī az-Zarqā’)

, ADAJ 55

Nigro, L., and E. Gallo. (2022) “Khirbet al-Batrawy 2015–2019: The Four-Lines Defensive System and the Entrance Hall of the Palace of the Copper Axes

.” Studies in the History

and Archaeology of Jordan 11: 161–177.

Nigro, L. (2024) Khirbet al-Batrawy, Archaeology In Jordan 4

Nigro, L. (2025) Khirbet al-Batrawy, 2020-2022: The Palace of the Copper Axes and the North-Eastern City fortifications

, Archaeology of Jordan, ICHAJ XV

Nigro, L. (ed.) (2006) KHIRBET AL-BATRAWY An Early Bronze Age Fortified Town in North-Central Jordan Preliminary Report of the First Season of Excavations (2005) ROSAPAT 03

Nigro, L. (ed.) (2008) KHIRBET AL-BATRAWY II The EB II city-gate, the EB II-III fortifications, the EB II-III temple Preliminary report of the second (2006) and third (2007) seasons of excavations ROSAPAT 06

Nigro, L. (ed.) (2012) KHIRBET AL-BATRAWY III The EB II-III triple fortification line, and the EB IIIB quarter inside the city-wall Preliminary report of the fourth (2008) and fifth (2009) seasons of excavations ROSAPAT 08

Nigro, L. (ed.) (2010) In The Palace of the Copper Axes. Khirbet al-Batrawy: The discovery of a forgotten city of the III millennium BC in Jordan

Publications Page of the Sapienza Expedition to Khirbet al-Batrawy website

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |