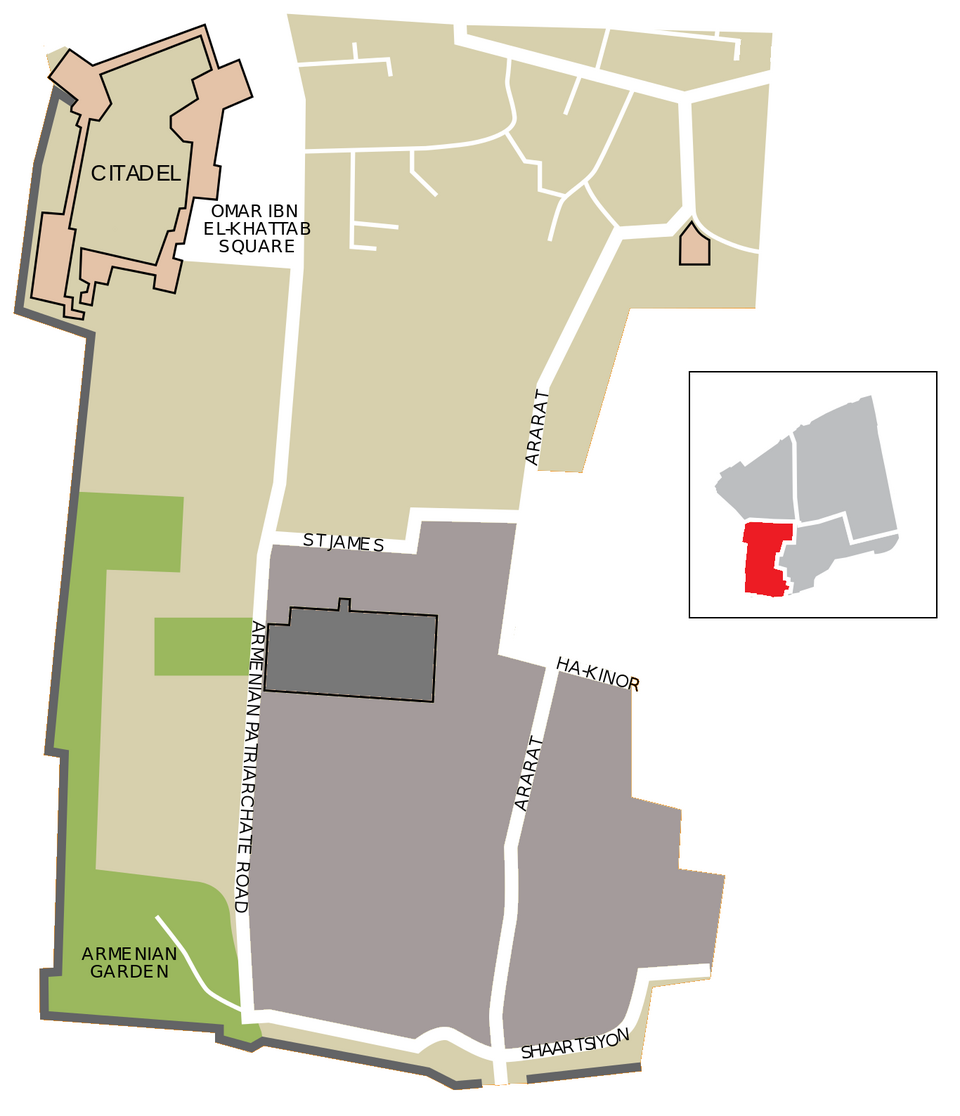

Jerusalem - Armenian Garden

- from Chat GPT 5, 1 November 2025

- sources: IAA Hadashot: Old City, Jaffa Gate (2019), IAA Hadashot: Armenian Patriarchate (2014), Tushingham (1985) Armenian Garden, Jerusalem Revealed (pdf), Armenian Quarter — Wikipedia

Soundings in the garden exposed Iron Age occupation, interpreted as an extra-mural quarter serving fields and terraces west of the city. Later works uncovered massive platform remains associated with the setting of Herod’s palatial complex near the western defenses, anchoring the area to the royal topography of early Roman Jerusalem.

Late Roman layers produced roof tiles and pipes stamped by the Tenth Legion, marking the military imprint on the quarter after 70 CE. Nearby exposures add street lines, workspaces, and domestic units that speak to the city’s planned rebuild as Aelia Capitolina and to its Byzantine flourishing.

Strata continue into the Umayyad and Abbasid eras, with ceramics and architecture indicating sustained urban life. Taken together, the Armenian Garden’s sequence offers a compact, readable cross-section: from rural margins, to royal precinct, to legionary town, to a multi-period urban neighborhood at the western approach to Mount Zion.

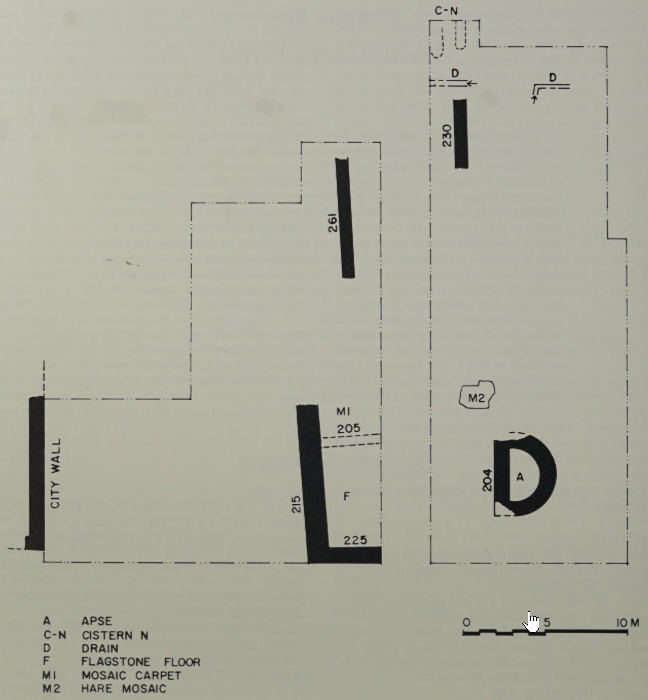

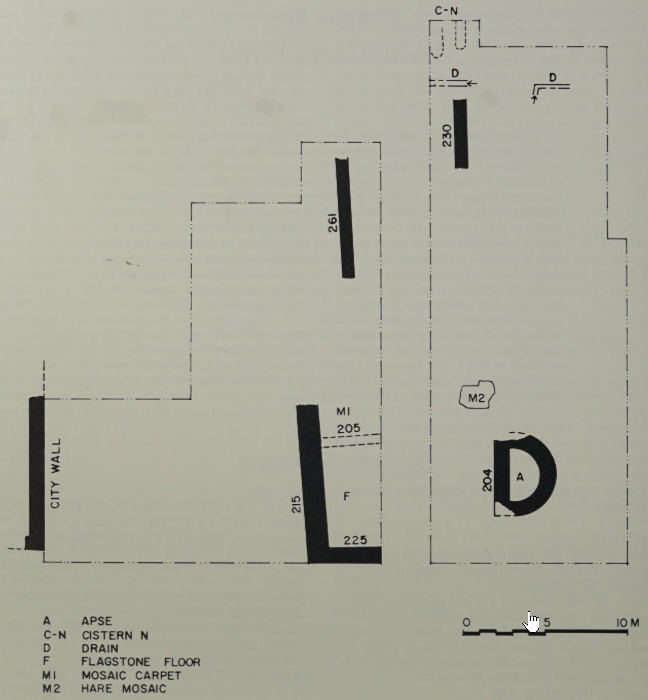

- Fig. 1 Byzantine I

phase from Tushingham (1985)

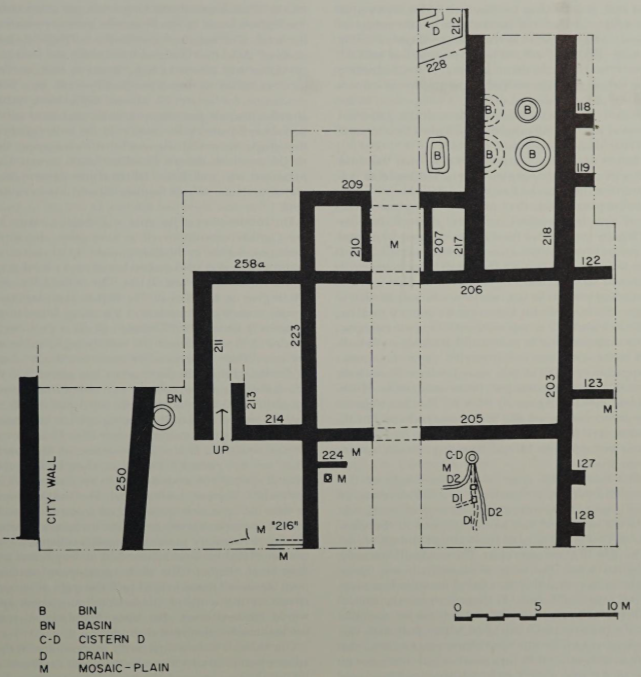

Figure 1

Figure 1

Byzantine I: The structure remains, as identified, do not provide a coherent picture, but stratigraphically they precede Byzantine II and they differ slightly from it in orientation. The apse suggests, and the Hare mosaic demonstrates, that the building wass - or included - a chapel or church.

click on image to open in a new tab

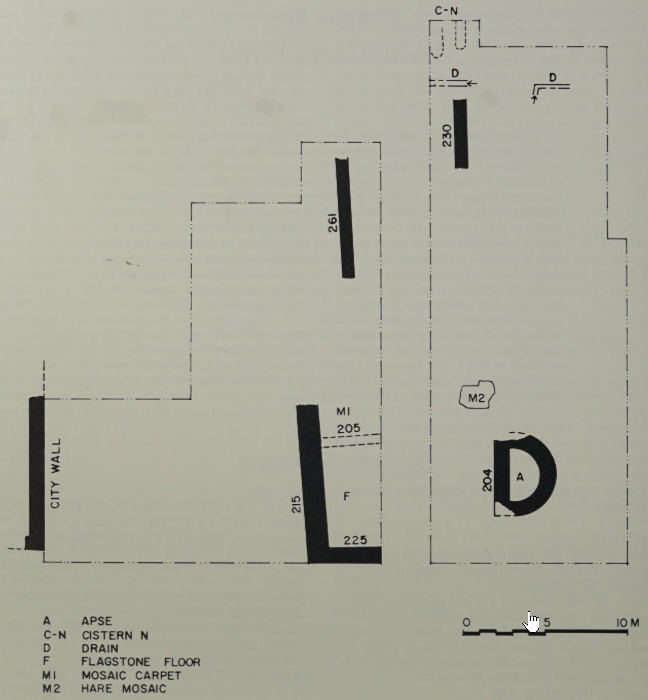

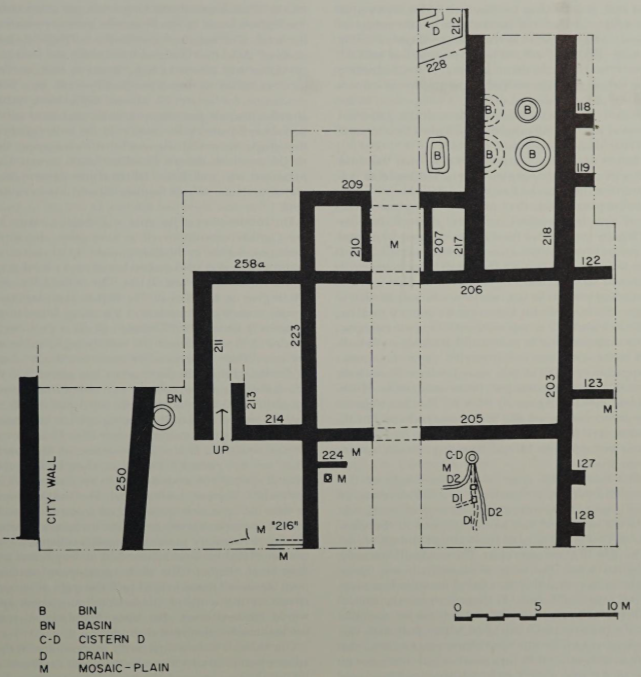

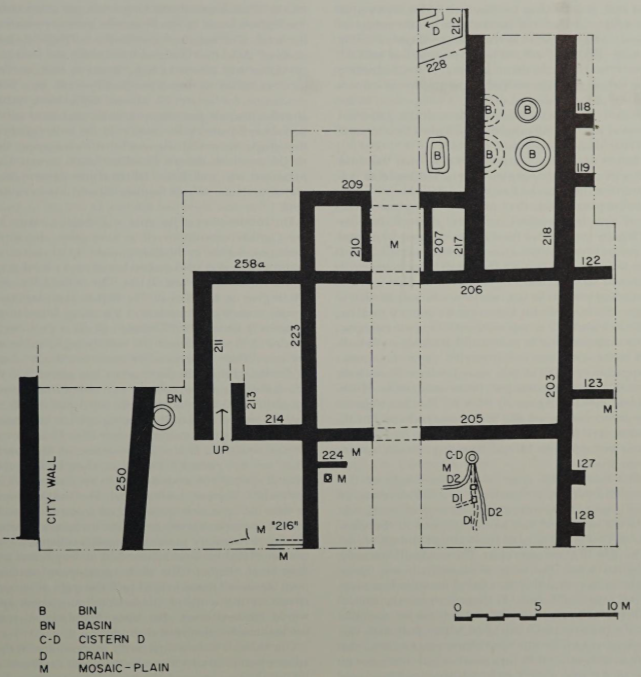

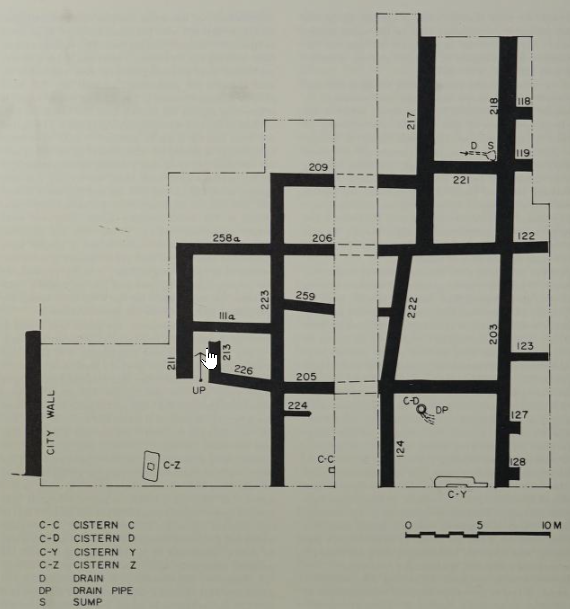

Tushingham (1985) - Fig. 2 Byzantine II

phase from Tushingham (1985)

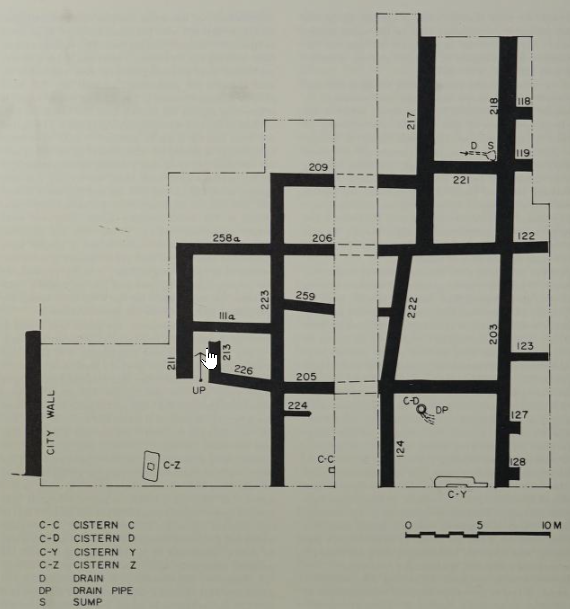

Figure 2

Byzantine I: The plan and orientation differ from those of the preceding Byzantine 1 structure. There is a central rectangular courtyard or room, bounded by walls 203, 205, 206, and 223, and surrounded by other rectangular loci, some roofed and some unroofed, but there is no evidence as to the manner of roofing. Some spaces may have been vaulted but no recognizable voussoirs were found in the debris preceding the mediaeval reuse of the building. A staircase leads to an upper storey or the roof. Reconstruction of the walls east of wall 203/218 and of the whole southeast corner (washed out at the end of Byzantine II) Is dependent on the assumption that the Byzantine II rebuilding followed the Byzantine II plan closely. The northwest corner of the building was not excavated.

click on image to open in a new tab

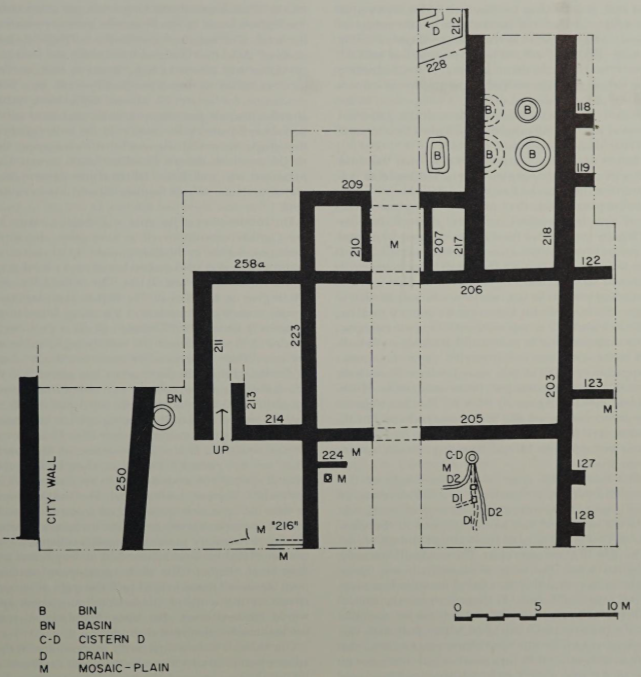

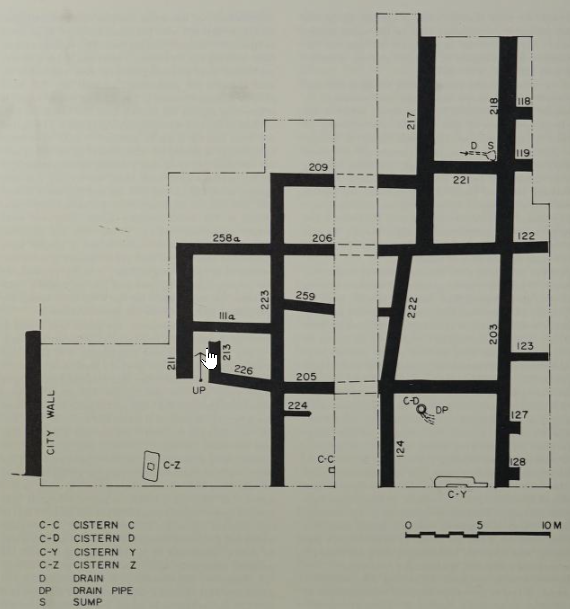

Tushingham (1985) - Fig. 3 Byzantine III

phase from Tushingham (1985)

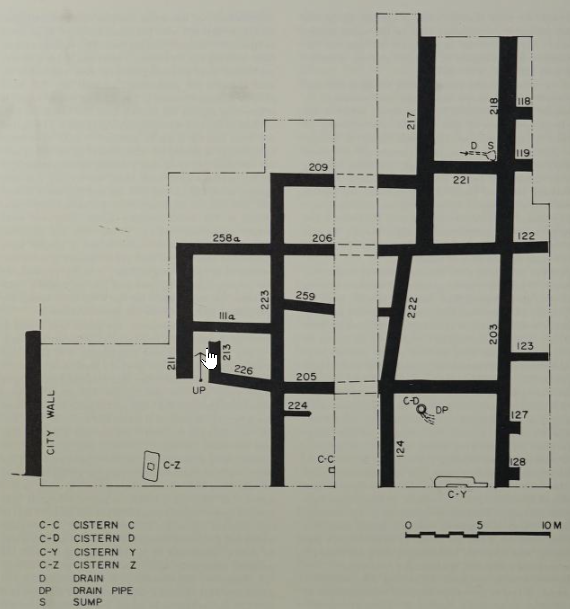

Figure 3

Figure 3

Byzantine III: After a major washout, the Byzantine III building followed the plan of its predecessor with a few minor changes: the central rectangular area was cut in half by wall 222, with rooms to the west of it wall 214 was rebuilt as wall 226 to accord with the southern end of wall 211, in part washed away; walls 118, 119, 122, 123, 127, and 128 were built (or rebuilt) in part as buttresses for wall 203/218. There is still a staircase to art upper storey or the roof.

click on image to open in a new tab

Tushingham (1985)

- Fig. 1 Byzantine I

phase from Tushingham (1985)

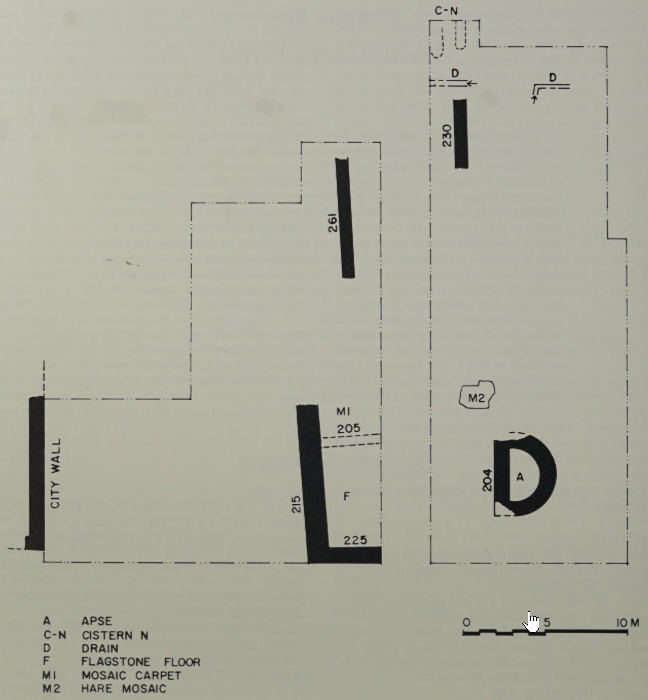

Figure 1

Figure 1

Byzantine I: The structure remains, as identified, do not provide a coherent picture, but stratigraphically they precede Byzantine II and they differ slightly from it in orientation. The apse suggests, and the Hare mosaic demonstrates, that the building wass - or included - a chapel or church.

click on image to open in a new tab

Tushingham (1985) - Fig. 2 Byzantine II

phase from Tushingham (1985)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Byzantine I: The plan and orientation differ from those of the preceding Byzantine 1 structure. There is a central rectangular courtyard or room, bounded by walls 203, 205, 206, and 223, and surrounded by other rectangular loci, some roofed and some unroofed, but there is no evidence as to the manner of roofing. Some spaces may have been vaulted but no recognizable voussoirs were found in the debris preceding the mediaeval reuse of the building. A staircase leads to an upper storey or the roof. Reconstruction of the walls east of wall 203/218 and of the whole southeast corner (washed out at the end of Byzantine II) Is dependent on the assumption that the Byzantine I rebuilding followed the Byzantine II plan closely. The northwest corner of the building was not excavated.

click on image to open in a new tab

Tushingham (1985) - Fig. 3 Byzantine III

phase from Tushingham (1985)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Byzantine III: After a major washout, the Byzantine III building followed the plan of its predecessor with a few minor changes: the central rectangular area was cut in half by wall 222, with rooms to the west of it wall 214 was rebuilt as wall 226 to accord with the southern end of wall 211, in part washed away; walls 118, 119, 122, 123, 127, and 128 were built (or rebuilt) in part as buttresses for wall 203/218. There is still a staircase to art upper storey or the roof.

click on image to open in a new tab

Tushingham (1985)

With its detailed publication, the excavations in the Armenian Garden under the direction of A. D. Tushingham27 from 1961 to 1967 provide lots of material for studying the Byzantine–Early Islamic period. This site might also show archaeological evidence for the AD 749 earthquake which was not interpreted as such by the excavator.

Three phases of buildings of the Byzantine–Early Islamic period were distinguished: the phase entitled ‘Byzantine I’, which clearly served a religious (Christian) purpose, likely a chapel or even a small church.28 Attributed to this phase are an apse, the ‘Hare Mosaic’, an additional mosaic, some cisterns, and a few walls.29 The excavators attribute this phase to the end of the reign of Justinian. A. D. Tushingham assumes this phase was short,30 suggesting an “abrupt end by a washout.”31

After that, a completely different constructed building sounded the bell for a new architectural phase in this area. The so-called ‘Byzantine II’ phase consists of a building erected with a completely different orientation. It had a central courtyard and three adjoining smaller rooms. A. D. Tushingham describes this building as a possible khan or a caravanserai.32

Additionally, an area enclosed with walls containing structures which are called ‘bins’, is attributed to this period.33 Their function is not entirely clear. The bins seem to have contained several pieces of burned plaster and burned stones as well as a large number of tiles.34 However, possible use as a kiln was excluded by the excavator.35 This phase was brought to an end by a ‘great washout’, similar to the previous one. It is described by A. D. Tushingham as follows: “It is difficult to believe that rains alone could have been responsible for such a flood, but there is no doubt that the water was the agent of the destruction.”36

The last phase, ‘Byzantine III’, was a reconstruction of the previous one but with a reduction of the large central courtyard, which was cut in half by an inserted wall.38 The excavator interpreted both of the latter buildings as a possible caravanserai or a pension for pilgrims.39

In the light of the interpretation of the DEI area I results, the transition between the different phases should be reassessed. A. D. Tushingham claims that the last of the phases, ‘Byzantine III’, was destroyed during the seventh century AD, either by the Persian conquest in AD 614 or by the ‘Muslim conquest’ in AD 638 and only resettled in the medieval period.40 Such an occupation gap does not seem very likely, considering that during the Umayyad period, the south-western hill was still a flourishing place, especially for Christian pilgrims, as is known from various sources.

However, A. D. Tushingham still reports excavated material, such as pottery and coins, from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, mainly in various fillings.41 This does indicate that the area was occupied during this period, but no architectural features were attributed to this period.

J. Magness reassessed the pottery assemblages found in the excavations of the Armenian Garden. She discovered that the pottery of the Byzantine levels includes a mixture of types that can be dated from the sixth to the eighth centuries AD. Therefore, she concludes that it might be possible that the settlement phase in the Armenian Garden cannot be dated exclusively to the Byzantine period but can also have continued throughout the Umayyad period.42 Considering again the archaeological evidence of continuous occupation from DEI area I,43 a similar inhabitation pattern throughout the Umayyad period in the nearby Armenian Garden seems very likely.

Therefore, the author suggests in the following a reassessment of the Byzantine occupational phases — at least the later ones — into the Early Islamic period. Instead of ‘washouts’ (or the ‘Muslim conquest’) which were described by the excavator, these events might be connected to the earthquake. Following each ‘washout’ the area was rebuilt differently. Similarities can be drawn with the excavation results of the nearby DEI area I — after the destructive earthquake, the urban layout was altered drastically, thus changing the nature of the site.

The transition between the excavator’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ in particular may be looked at here: from a chapel to an architecturally completely different, possible caravanserai.

Two possible solutions can be considered for the reconstruction of the Armenian Garden’s history:

Either the earthquake occurred between Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ and as a consequence, the former chapel with an apse was overbuilt by the suggested caravanserai (instead of rebuilding the chapel). In any case, these measures changed the nature of the site altogether. The other option is the modification of the caravanserai in Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine II’ and ‘Byzantine III’ might be a possible result of rebuilding measures following the earthquake.44

J. Magness has also reassessed the dating of the repairing of the city wall to the Early Islamic period (see below); as is analysed by A. D. Tushingham, this repair work corresponds with his ‘Byzantine II’ period.45 This dating would confirm that Tushingham’s ‘Byzantine II’ phase can be dated post-earthquake.

Consequently, the ‘Byzantine III’ phase was a time in which the Armenian Garden was extensively repaired and rebuilt. Perhaps this was necessary after a destructive event, such as an earthquake, similar to DEI area I.

Furthermore, the so-called ‘bins’ mentioned above, which can also be attributed to the possible early Islamic layers, contain a lot of burnt material and former building material, such as burnt plaster and tiles, as described by A. D. Tushingham.47 It can be suggested that this material could be the remains of the destroyed former buildings, the ‘Byzantine I’ structures. Those ‘bins’ were sealed, as described by A. D. Tushingham, by the latest ‘Byzantine III’ floor, which supports that argument.48 For this, a detailed find analysis of the content of these ‘bins’ would be necessary.

Certainly, this chapter cannot provide a complete detailed reassessment of all the stratigraphical contexts and corresponding finds of the excavation in the Armenian Garden; still, it can provide cause to reconsider the archaeological history of the site during the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period.

27 From 1962 onwards; the first year (1961) was under the

direction of R. de Vaux and J. A. Callaway (Tushingham 1985, 3).

28 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

29 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

30 Without providing a further time frame for “short.”

31 Tushingham 1985, 101. It remains uncertain what exactly

is meant by “washout.”

32 Tushingham 1985, 104.

33 Tushingham 1985, 101–02, pl. 6.

34 Tushingham 1985, 79.

35 Tushingham 1985, 79.

36 Tushingham 1985, 69.

37 Which is actually subdivided into IIIA

(redressing the damage caused by the previous 'washout') and IIIB

(actual rebuilding measures; Tushingham 1985, 103).

38 Tushingham 1985, 103–04.

38 Tushingham 1985. 103-04.

39 Tushingham 1985. 104.

40 Tushingham 1985, 104-05. Many earlier scholars,

especially from the 1960s and 1970s, attributed any

urban changes during this period to the `Muslim

conquest, neglecting the possibility of the AD 749

earthquake. But this view is no longer reflected in

modern research (Avni 2014, 14).

41 Tushingham 1985, 105-06. He wrote that the majority of

the Umayyad and Abbasid coins stems from 'deposits

that on stratigraphic grounds can be assigned to the

fills chat precede the first medieval, that is Ayyubid,

occupation of the site' (Tushingham 1985, 106).

42 Magness 1991, 212.

43 Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024.

44 We must also consider the possibility that several earthquakes

or aftershocks occurred in a short time, causing two different

“washouts” in the Armenian Garden.

45 Keeping in mind, that these repairs are either a result of the

earthquake or might also be the result of the reconstruction of the

city walls by Caliph Hisham.

46 Tushingham 1985, 65.

47 Tushingham 1985, 79.

48 Tushingham 1985, 79.

With its detailed publication, the excavations in the Armenian Garden under the direction of A. D. Tushingham27 from 1961 to 1967 provide lots of material for studying the Byzantine–Early Islamic period. This site might also show archaeological evidence for the AD 749 earthquake which was not interpreted as such by the excavator.

Three phases of buildings of the Byzantine–Early Islamic period were distinguished: the phase entitled ‘Byzantine I’, which clearly served a religious (Christian) purpose, likely a chapel or even a small church.28 Attributed to this phase are an apse, the ‘Hare Mosaic’, an additional mosaic, some cisterns, and a few walls.29 The excavators attribute this phase to the end of the reign of Justinian. A. D. Tushingham assumes this phase was short,30 suggesting an “abrupt end by a washout.”31

After that, a completely different constructed building sounded the bell for a new architectural phase in this area. The so-called ‘Byzantine II’ phase consists of a building erected with a completely different orientation. It had a central courtyard and three adjoining smaller rooms. A. D. Tushingham describes this building as a possible khan or a caravanserai.32

Additionally, an area enclosed with walls containing structures which are called ‘bins’, is attributed to this period.33 Their function is not entirely clear. The bins seem to have contained several pieces of burned plaster and burned stones as well as a large number of tiles.34 However, possible use as a kiln was excluded by the excavator.35 This phase was brought to an end by a ‘great washout’, similar to the previous one. It is described by A. D. Tushingham as follows: “It is difficult to believe that rains alone could have been responsible for such a flood, but there is no doubt that the water was the agent of the destruction.”36

The last phase, ‘Byzantine III’, was a reconstruction of the previous one but with a reduction of the large central courtyard, which was cut in half by an inserted wall.38 The excavator interpreted both of the latter buildings as a possible caravanserai or a pension for pilgrims.39

In the light of the interpretation of the DEI area I results, the transition between the different phases should be reassessed. A. D. Tushingham claims that the last of the phases, ‘Byzantine III’, was destroyed during the seventh century AD, either by the Persian conquest in AD 614 or by the ‘Muslim conquest’ in AD 638 and only resettled in the medieval period.40 Such an occupation gap does not seem very likely, considering that during the Umayyad period, the south-western hill was still a flourishing place, especially for Christian pilgrims, as is known from various sources.

However, A. D. Tushingham still reports excavated material, such as pottery and coins, from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, mainly in various fillings.41 This does indicate that the area was occupied during this period, but no architectural features were attributed to this period.

J. Magness reassessed the pottery assemblages found in the excavations of the Armenian Garden. She discovered that the pottery of the Byzantine levels includes a mixture of types that can be dated from the sixth to the eighth centuries AD. Therefore, she concludes that it might be possible that the settlement phase in the Armenian Garden cannot be dated exclusively to the Byzantine period but can also have continued throughout the Umayyad period.42 Considering again the archaeological evidence of continuous occupation from DEI area I,43 a similar inhabitation pattern throughout the Umayyad period in the nearby Armenian Garden seems very likely.

Therefore, the author suggests in the following a reassessment of the Byzantine occupational phases — at least the later ones — into the Early Islamic period. Instead of ‘washouts’ (or the ‘Muslim conquest’) which were described by the excavator, these events might be connected to the earthquake. Following each ‘washout’ the area was rebuilt differently. Similarities can be drawn with the excavation results of the nearby DEI area I — after the destructive earthquake, the urban layout was altered drastically, thus changing the nature of the site.

The transition between the excavator’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ in particular may be looked at here: from a chapel to an architecturally completely different, possible caravanserai.

Two possible solutions can be considered for the reconstruction of the Armenian Garden’s history:

Either the earthquake occurred between Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ and as a consequence, the former chapel with an apse was overbuilt by the suggested caravanserai (instead of rebuilding the chapel). In any case, these measures changed the nature of the site altogether. The other option is the modification of the caravanserai in Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine II’ and ‘Byzantine III’ might be a possible result of rebuilding measures following the earthquake.44

J. Magness has also reassessed the dating of the repairing of the city wall to the Early Islamic period (see below); as is analysed by A. D. Tushingham, this repair work corresponds with his ‘Byzantine II’ period.45 This dating would confirm that Tushingham’s ‘Byzantine II’ phase can be dated post-earthquake.

Consequently, the ‘Byzantine III’ phase was a time in which the Armenian Garden was extensively repaired and rebuilt. Perhaps this was necessary after a destructive event, such as an earthquake, similar to DEI area I.

Furthermore, the so-called ‘bins’ mentioned above, which can also be attributed to the possible early Islamic layers, contain a lot of burnt material and former building material, such as burnt plaster and tiles, as described by A. D. Tushingham.47 It can be suggested that this material could be the remains of the destroyed former buildings, the ‘Byzantine I’ structures. Those ‘bins’ were sealed, as described by A. D. Tushingham, by the latest ‘Byzantine III’ floor, which supports that argument.48 For this, a detailed find analysis of the content of these ‘bins’ would be necessary.

Certainly, this chapter cannot provide a complete detailed reassessment of all the stratigraphical contexts and corresponding finds of the excavation in the Armenian Garden; still, it can provide cause to reconsider the archaeological history of the site during the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period.

27 From 1962 onwards; the first year (1961) was under the

direction of R. de Vaux and J. A. Callaway (Tushingham 1985, 3).

28 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

29 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

30 Without providing a further time frame for “short.”

31 Tushingham 1985, 101. It remains uncertain what exactly

is meant by “washout.”

32 Tushingham 1985, 104.

33 Tushingham 1985, 101–02, pl. 6.

34 Tushingham 1985, 79.

35 Tushingham 1985, 79.

36 Tushingham 1985, 69.

37 Which is actually subdivided into IIIA

(redressing the damage caused by the previous 'washout') and IIIB

(actual rebuilding measures; Tushingham 1985, 103).

38 Tushingham 1985, 103–04.

38 Tushingham 1985. 103-04.

39 Tushingham 1985. 104.

40 Tushingham 1985, 104-05. Many earlier scholars,

especially from the 1960s and 1970s, attributed any

urban changes during this period to the `Muslim

conquest, neglecting the possibility of the AD 749

earthquake. But this view is no longer reflected in

modern research (Avni 2014, 14).

41 Tushingham 1985, 105-06. He wrote that the majority of

the Umayyad and Abbasid coins stems from 'deposits

that on stratigraphic grounds can be assigned to the

fills chat precede the first medieval, that is Ayyubid,

occupation of the site' (Tushingham 1985, 106).

42 Magness 1991, 212.

43 Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024.

44 We must also consider the possibility that several earthquakes

or aftershocks occurred in a short time, causing two different

“washouts” in the Armenian Garden.

45 Keeping in mind, that these repairs are either a result of the

earthquake or might also be the result of the reconstruction of the

city walls by Caliph Hisham.

46 Tushingham 1985, 65.

47 Tushingham 1985, 79.

48 Tushingham 1985, 79.

Magness, J. (1991). The Walls of Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period. The Biblical Archaeologist, 54(4), 208–217.

Tushingham, A. D. (1985) Excavations in Jerusalem 1961-1967, I (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum). - can be borrowed with a free account from archive.org

Zimni, J. (2023) 'Urbanism in Jerusalem from the Iron Age to the Medieval Period at the Example of the DEI Excavations on Mount Zion'

(unpublished doctoral thesis, Bergische Universitic Wuppertal)

Zimni-Gitler, J. (2025) Chapter 10. Traces of the AD 749 Earthquake in Jerusalem: New Archaeological Evidence from Mount Zion

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis