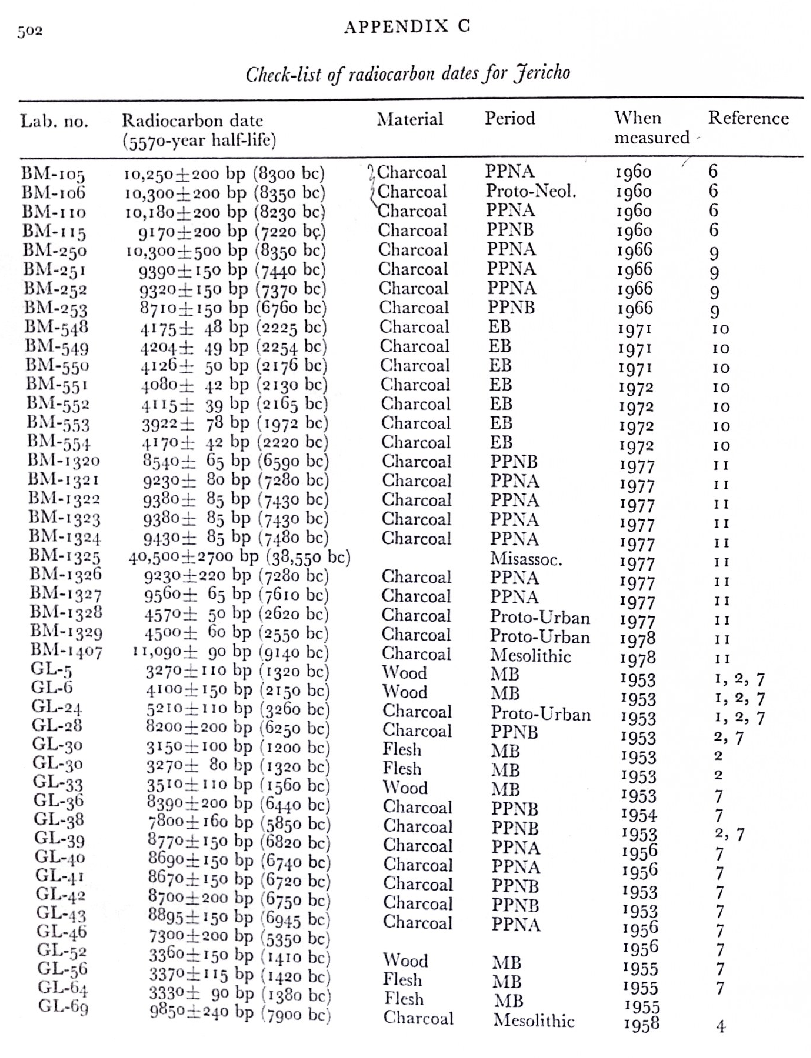

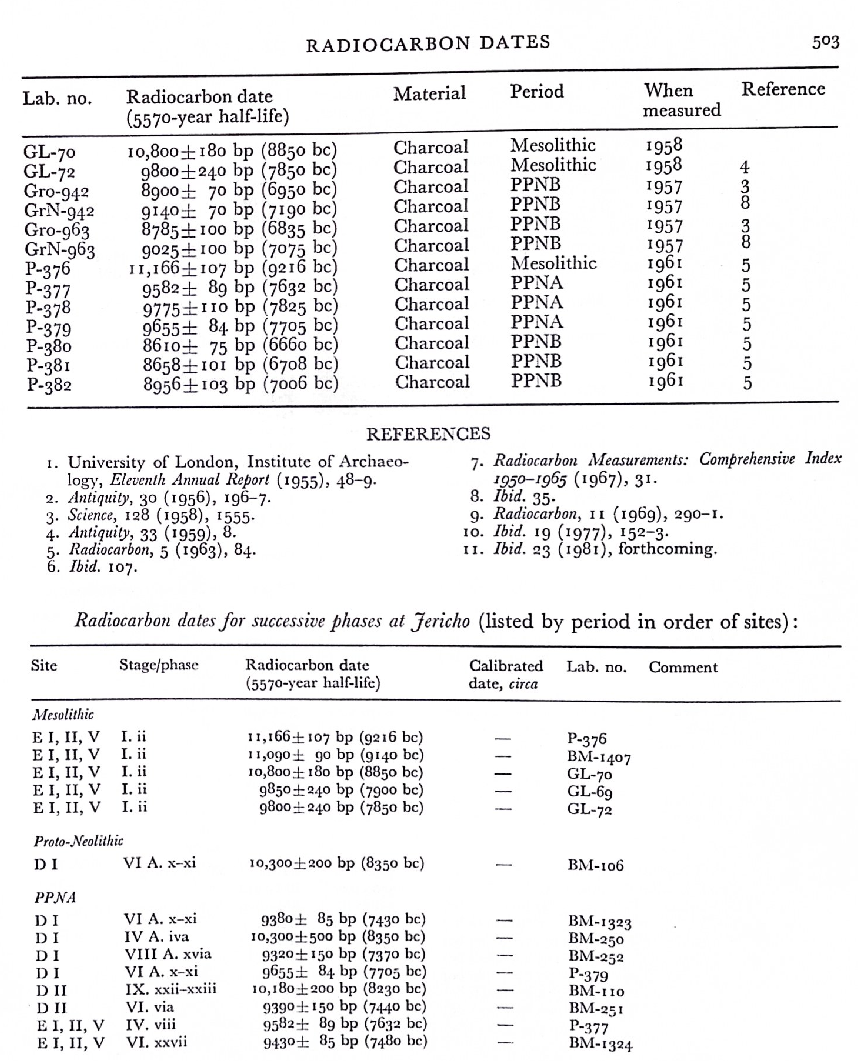

Tell Es-Sultan (Jericho)

Aerial view of Tell Es-Sultan

Aerial view of Tell Es-Sultanclick on image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Fullo88 - Italian Wikipedia - Public Domain

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tel Jericho | English | |

| Ancient Jericho | English | |

| Tell es-Sultan | Arabic | تل السلطان |

Jericho enters written history as the first town west of the Jordan River to be captured by the Israelites approaching from the east. Joshua's instruction to his spies to "Go, view the land, especially Jericho" (Jos. 2:1) is an illustration of the position of Jericho in the age-long process of penetration by nomads and seminomads from the desert area in the east into the fertile coastal lands. It stood near the Jordan fords between a good valley route down the eastern side of the Jordan Valley and another going up the western mountains. As it dominated one of the few routes leading directly from east to west, it was liable to attack by successive invaders.

The identification of the main mound of the oasis, Tell es-Sultan (map reference 192.142), with the oldest city is generally accepted. The mound rises to a height of 21.5 m and covers an area of about one acre. It stands quite near 'Ein es-Sultan (Elisha's Well). As regards the Jericho of the Book of Joshua, there are some chronological difficulties, as will be seen below. Following its destruction by Joshua, the Bible states, Jericho was abandoned for centuries until a new settlement was established by Hiel the Bethelite (1 Kg. 16:34), in the time of Ahab, in the ninth century BCE. Other biblical references do not suggest that Jericho ever recovered its importance. The archaeological evidence shows that occupation on the ancient site came to an end at the time of the Babylonian Exile. The centers of the later Jerichos were elsewhere in the Oasis.

The first references to Jericho in the Hebrew Bible are in the books of Numbers (22:1, 26:3), where the encampment of Israel is described across the river from the town; of Deuteronomy (34:1, 3), where the site is named; and of Joshua (2:1-3, 5:13-6:26), where it is recorded that spies were sent to examine the city and that the town was surrounded and conquered. The modern name of the mound, Tell es-Sultan, is the medieval name given to the site because it is located at the spring of 'Am es-Sultan ("Elisha's fountain"). During the period of the Judges, when the site was purportedly occupied by Eglon of Moab, the town was also known as the "city of palm trees" (Jgs. 3:13).

Soundings at Tell es-Sultan were first made by C. Warren in 1868 as part of the early campaigns of the British Palestine Exploration Fund. Warren sank a number of shafts into the mound and concluded that there was nothing to be found. Two of his shafts were identified in the 1957-1958 excavations, one of them penetrating the Early Bronze Age town wall and the other missing the great Pre-Pottery Neolithic stone tower by only one meter.

The first large-scale excavations were those of an Austro-German expedition, from 1907 to 1909, under the direction of E. Sellin and C. Watzinger. The expedition cleared the face of a considerable part of the Early Bronze Age town wall and traced the line of about half of the revetment at the base of the Middle Bronze Age defenses. Within the town, a large area of houses was cleared at the north end and a great trench was cut across the center. Reexcavation in 1953 showed that it had penetrated well into the Pre-Pottery Neolithic levels. The excavations were conducted and published by the best standards of the time. Unfortunately, at that time, there was no accepted chronology, so that the usefulness of this early work is limited.

By the time new excavations were undertaken by the Neilson expeditions, directed by J. Garstang, from 1930 to 1936, the knowledge of pottery chronology had greatly increased. Excavation technique lagged, however, and the absence of detailed stratigraphy still often made the dating of the structures mere guesswork. The dating of the successive Bronze Age defensive systems by Garstang has, in fact, proved to be wrong. No Late Bronze Age wall survives. Also, as knowledge of pottery chronology increased, the dating given to the scanty Late Bronze Age levels from the mound and the tombs was shown to be incorrect. Garstang's most important discovery was that beneath the Bronze Age levels there was a deep Neolithic accumulation, usually of the Pre-Pottery stage. He believed that there was a transition to the use of pottery at the site, but this was a mistake. A third major series of excavations was carried out between 1952 and 1958, directed by K. M. Kenyon on behalf of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

Because of its biblical connections, the site of Jericho inspired considerable attention for nearly fifteen hundred years before the advent of modern archaeological research. Many pilgrims and travelers visited the area during the first millennium CE, the first written account, in 333 CE, being that of the Pilgrim of Bordeau (described in Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099-1185, by John Wilkinson, with Joyce Hill and W. F. Ryan, London, 1988, p. 4 [JW: bookmarked to the page at archive.org]). It was not until 1868, however, that the first archaeological investigation of the mound was undertaken by Charles Warren, on behalf of the British Palestine Exploration Fund. Warren excavated east-west trenches on the mound and sank 2.4 sq. m shafts 6.1 m into the earth (Warren, 1869, pp. 14-16) . Although Warren dug through the EB town wall and found artifacts, he did not consider that the excavated material remains (pottery and stone mortars) were very important occupational finds for dating successive historical periods. Warren's conclusion regarding Jericho and other similar sites was: "The fact that in the Jordan valley these mounds generally stand at the mouths of the great wadies, is rather in favour of their having been the sites of ancient guard-houses or watch-towers" (Warren, 1869, p. 210).

The site was more seriously investigated when Claude R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener made a topographical survey of Jericho and its surroundings, published in The Survey of Western Palestine, vol. 3 (London, 1883). The second archaeological expedition to the site was conducted by an Austro-German team directed by Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger between 1907 and 1909 and in 1911, under the sponsorship of the German Oriental Society (Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft); the results appeared in Jericho: Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen (Leipzig, 1913). The large portion of the mound excavated revealed much of the Middle Bronze Age glacis, which originally surrounded the town, as well as portions of the EB town walls. Houses belonging to the Israelite occupation of the town (eleventh-early sixth centuries BCE) were discovered on the southeast side of the mound. Controversy over the dating and capture of Jericho by Joshua has centered around two main schools of thought. The first theory conforms essentially to the biblical view that the Israelite occupation occurred with military attacks on Canaanite cities (a view primarily maintained by William Foxwell Albright, G. Ernest Wright, and John Bright). The second theory is that the conquest was a gradual and peaceful assimilation process that occurred in about 1200 BCE, at the beginning of the Iron Age (a view held by Albrecht Alt and Martin Noth and more recently discussed by Manfred Weippert [1971], and Israel Finkelstein [1988]).

In an effort to obtain further archaeological evidence concerning this question, excavations were conducted at Jericho from 1930 to 1936 by John Garstang. He led the Marston Melchett Expedition on behalf of the University of Liverpool and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. Garstang excavated many areas on the mound and also located a number of MB and LB tombs in the necropolis associated with the site (Garstang, 1932, pp. 18-22, 41-54; 1933a PP- 4-42; Bienkowski, 1986, pp. 32-102). Garstang originally claimed that the Israelites had indeed destroyed Jericho on the evidence of fallen walls he dated to the end of the Late Bronze Age, but he later revised their destruction to a much earlier period. Although the Joshua controversy was not solved, Garstang did reveal the very early Mesolithic and Neolithic stages of occupation on the site.

In an effort to resolve the Joshua problem and to clarify the results of Garstang's excavations, Kathleen M. Kenyon directed the most recent archaeological work at Jericho (1952-1958), sponsored by the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Palestine Exploration Fund, and the British Academy in collaboration with the American School of Oriental Research (now Albright Institute) in Jerusalem and the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (Kenyon, 1957, i960, 1965, 1981; Kenyon and Holland, 1982, 1983). The Kenyon expedition excavated a large number of tombs in the necropolis dating from the Proto-Urban period (c. 3400- 3100 BCE) to the Roman period. Although much of the ancient mound had already been dug by the previous two expeditions, Kenyon was able to plot three main trenches on the north (trench II), west (trench I), and south (trench III) slopes of the tell in order to obtain comparative stratigraphical cross-sections of the main fortification systems of different historical periods. She also excavated a number of large squares inside tlie walls of the town in order to crosscheck the results of the former excavations as well as to expose larger areas of the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods of occupation; these squares are lettered and numbered

- A I—II (grid E4-5, on the highest part of the tell, 24 m high)

- D I

- D II (grid H4-5, east end of trench I)

- E I-V (grid E-F6-7, northeast side of the tell)

- F I (grid G4-5, northeast end of trench I)

- H I-VI (grid H6-7 , east side of the mound above the spring)

- L I (grid G5-6 , center of the mound)

- M I (grid F-G5 , overlapping the EB town wall on the northwestern side of the mound)

- Fig. 5 Geological sketch

of the Tell es-Sultan and surrounding area from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Geological sketch of the Tell es-Sultan surrounding area. Fault traces (Roth, 1970; Begin, 1974; Shamir et al., 2005; Shamir, 2006) and the location of Tell and other major sites of great cultural interest are reported. Photos:

- fault zone in a Cretaceous deposit northeast of the Tell

- view from the southeast of a northeast—southwest-trending scarp (red arrows point the crest) along the Nuweime fault trace. Tell es-Sultan is in the background

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Location Map from Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

- Fig. 1 - Location Map from Netzer (1975)

- Fig. 37 Aerial view of the mound of Jericho from Kenyon (1978)

- Fig. 1 Satellite view

of the Jericho Oasis with the site of Tell es-Sultan and the main geomorphological features from Nigro (2014)

- Tell es-Sultan in Google Earth

- Tell es-Sultan on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 37 Aerial view of the mound of Jericho from Kenyon (1978)

- Fig. 1 Satellite view

of the Jericho Oasis with the site of Tell es-Sultan and the main geomorphological features from Nigro (2014)

- Tell es-Sultan in Google Earth

- Tell es-Sultan on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Site Plan with

excavations areas of Garstang, Kenyon, and the Italian-Palestinians from Nigro and Taha (2006)

- Fig. 2 Site Plan from

Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 6 Site Plan of EB II

(3000–2700 B.C.E) city of Jericho from Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 8 Site Plan of EB III

city of Jericho from Nigro (2016)

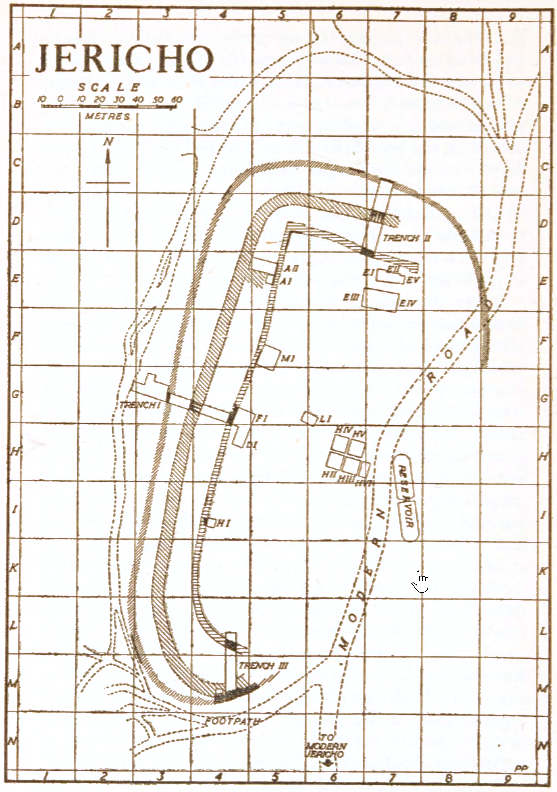

- Fig. 3 Site Plan from Kenyon (1957)

- Site Plan and Excavation Areas

from Kathleen Kenyon in Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

- Fig. 1 Composite sketch

from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

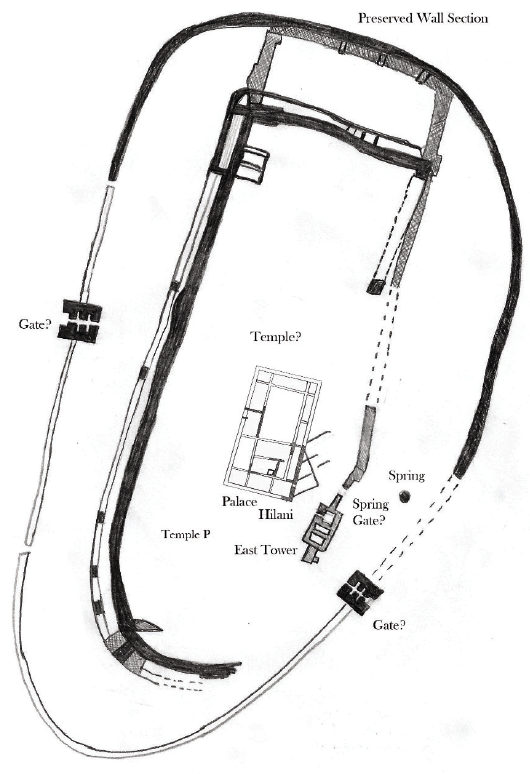

- Fig. 1 Composite map of

Jericho from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 2 Plan of Pre-Pottery

Neolithic Town Walls from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 3 Plan of Early Bronze Age Town Walls from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 4 Plan of Middle Bronze

Age town rampart and revetment from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 2 Site Plan with

excavations areas of Garstang, Kenyon, and the Italian-Palestinians from Nigro and Taha (2006)

- Fig. 2 Site Plan from

Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 6 Site Plan of EB II

(3000–2700 B.C.E) city of Jericho from Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 8 Site Plan of EB III

city of Jericho from Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 3 Site Plan from Kenyon (1957)

- Site Plan and Excavation Areas

from Kathleen Kenyon in Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

Tell es-Sultan: plan of the site and excavation areas

Tell es-Sultan: plan of the site and excavation areas

- City wall from Early Bronze Age; in west it is built directly above Neolithic wall

- Retaining wall of glacis from Middle Bronze Age II

- Glacis;

- Kenyon's trench I

- Trench II

- Trench III

- Road

- Pools near spring

Click on image to open in a new tab

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2) - Fig. 1 Composite sketch

from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 1 Composite map of

Jericho from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 2 Plan of Pre-Pottery

Neolithic Town Walls from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 3 Plan of Early Bronze Age Town Walls from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

- Fig. 4 Plan of Middle Bronze

Age town rampart and revetment from Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

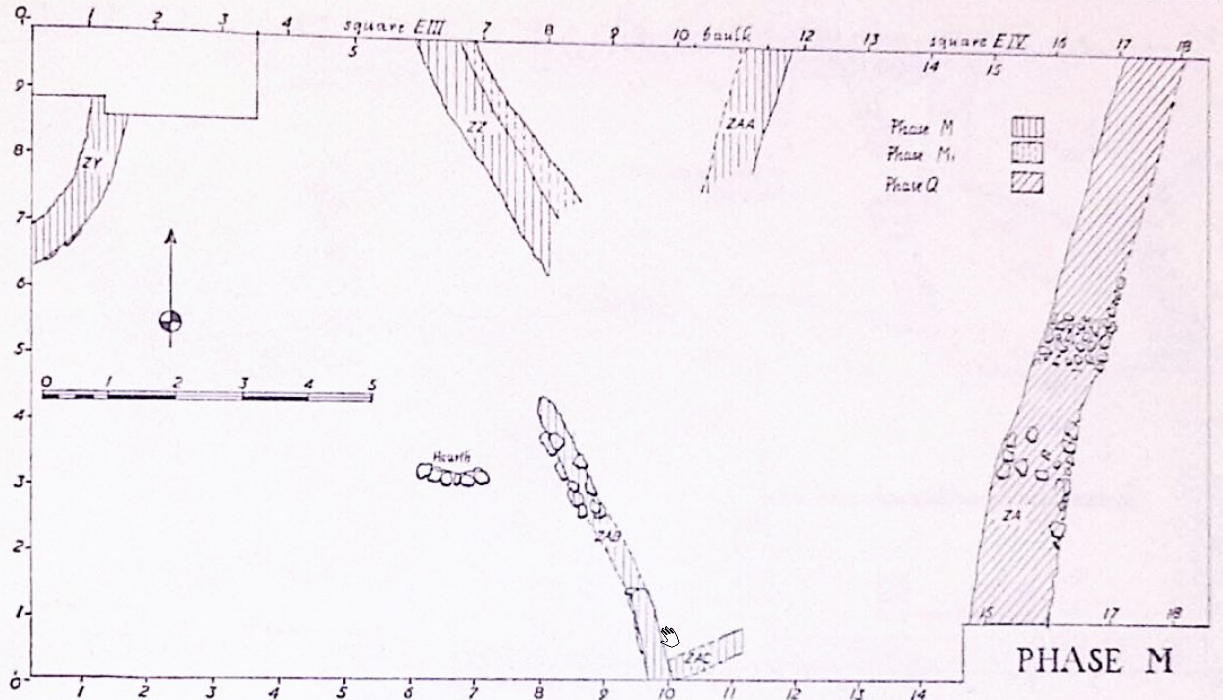

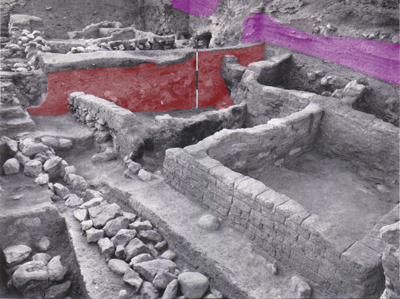

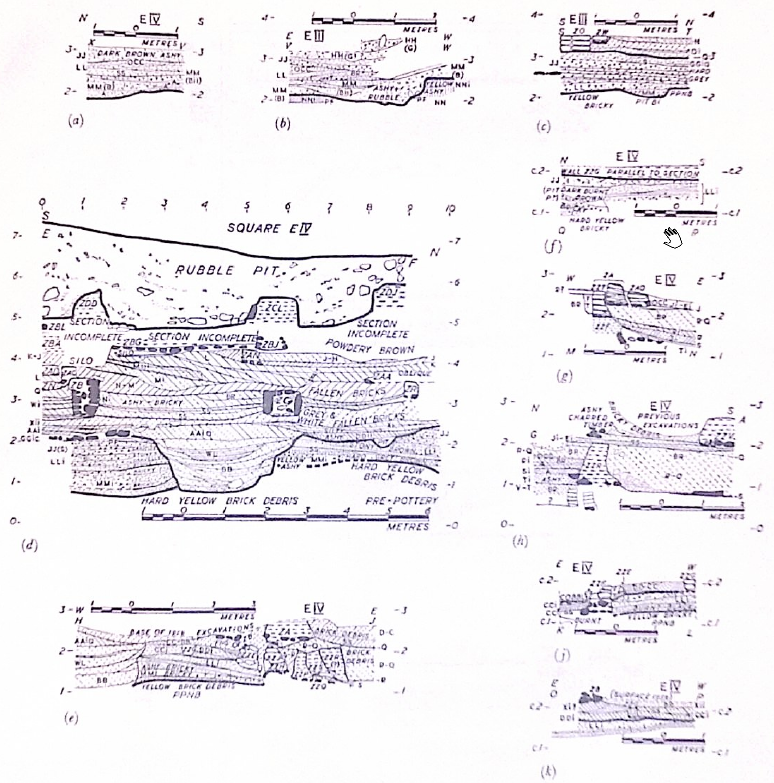

- Pl. 315a Phases M, Mi, and

Q in Squares EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Pl. 315a Phases M, Mi, and

Q in Squares EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

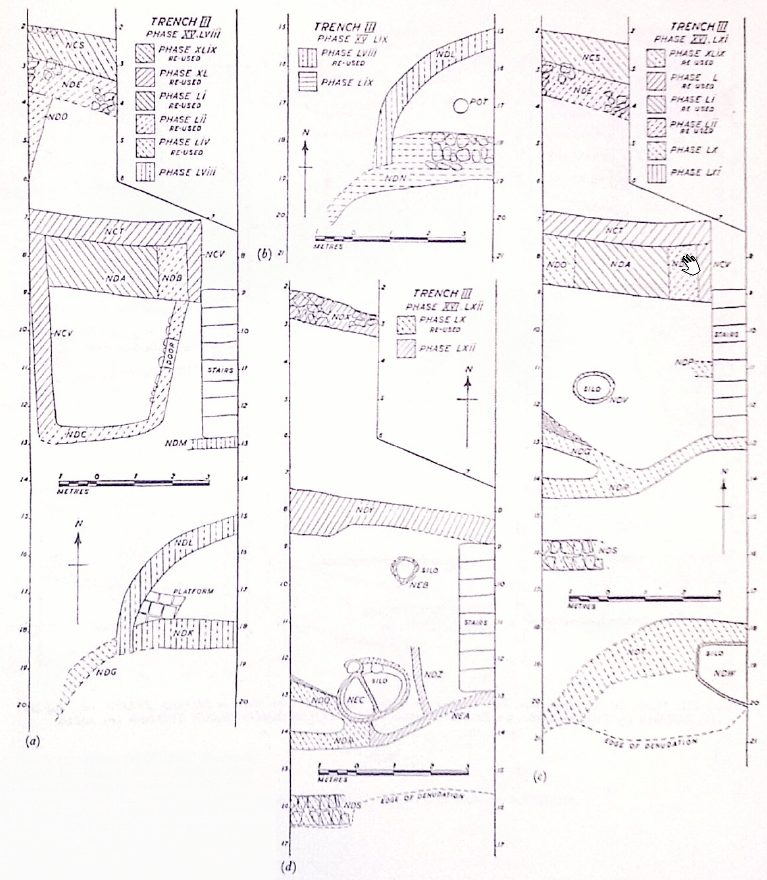

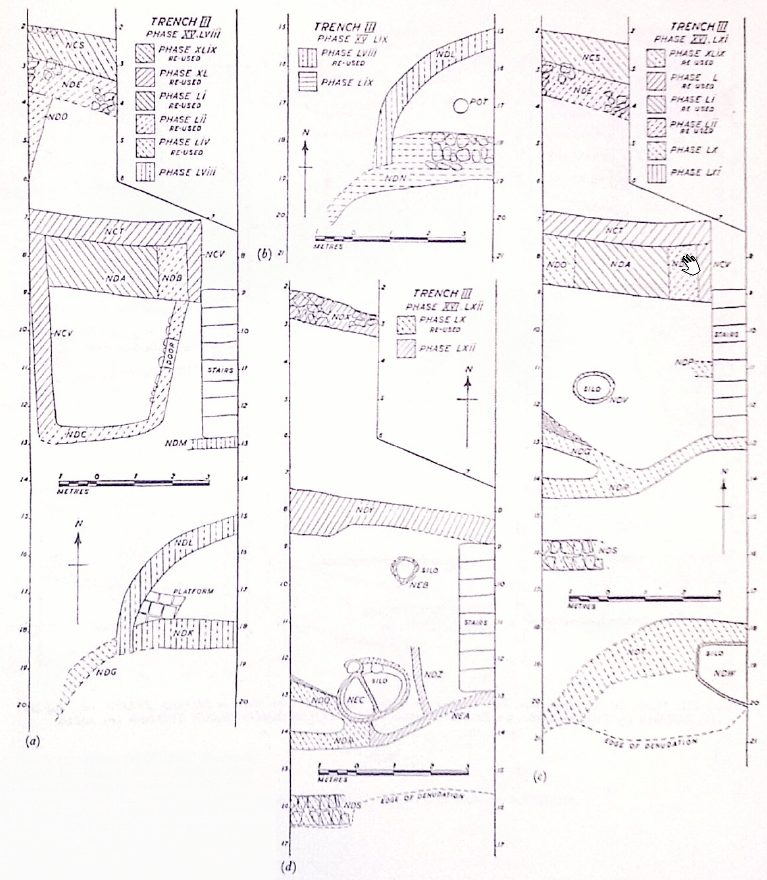

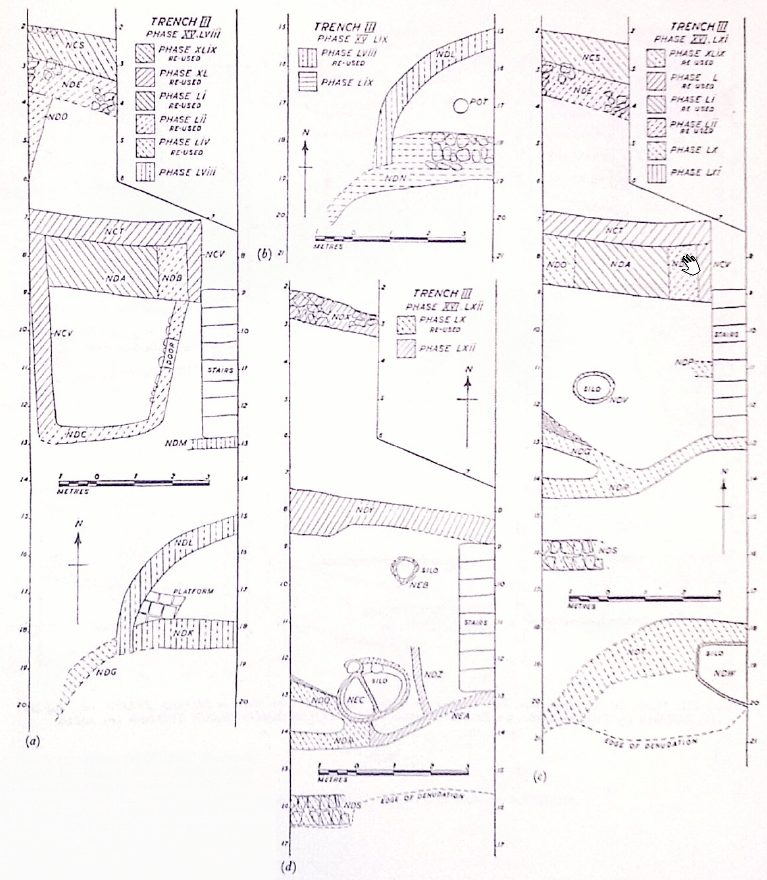

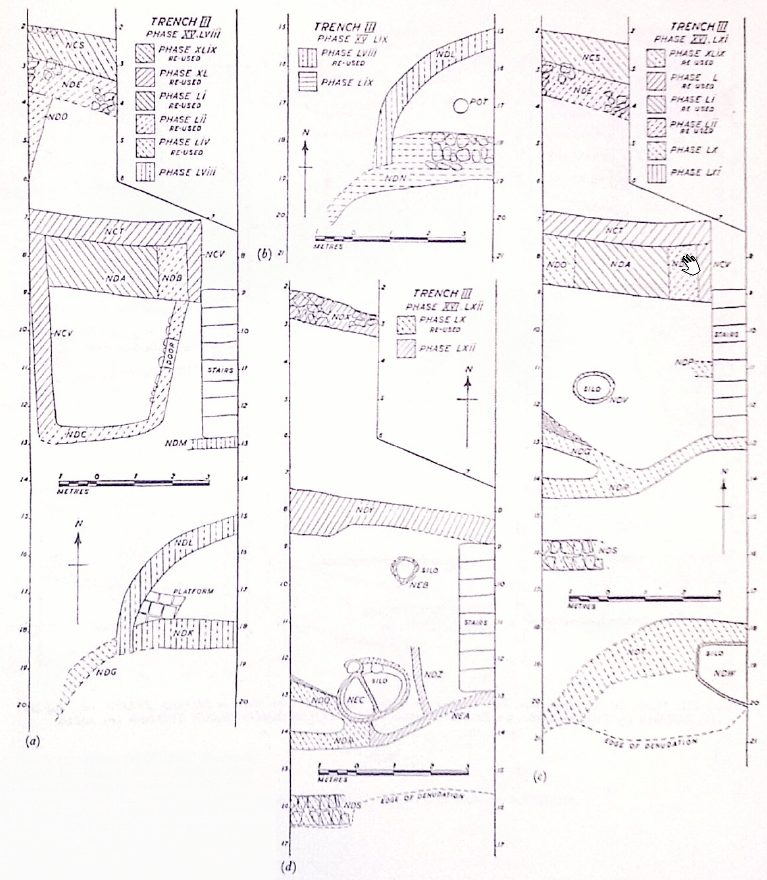

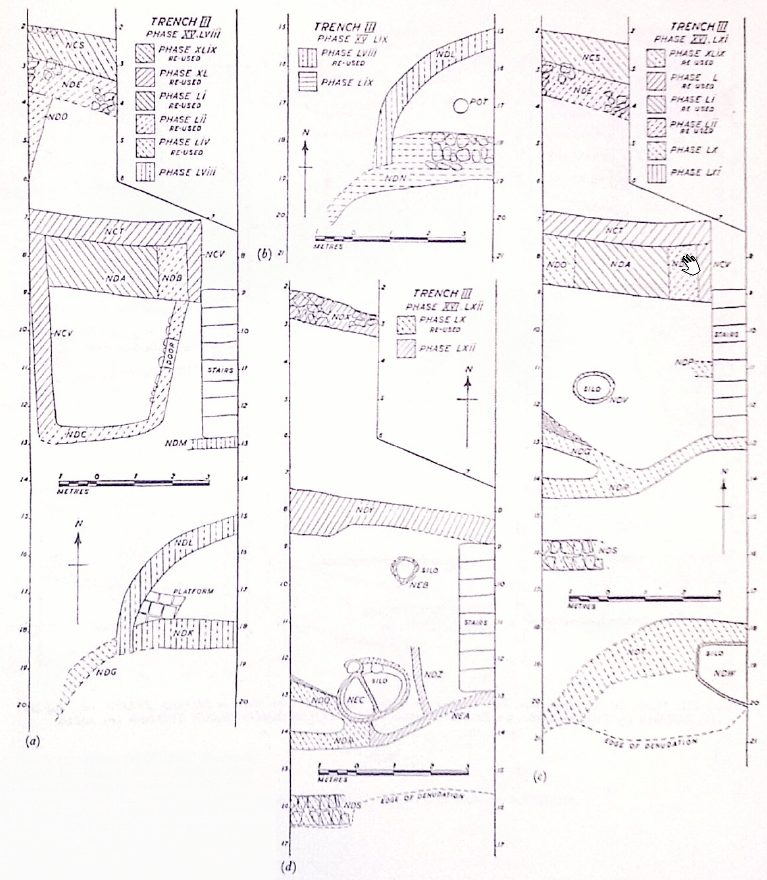

- Pl. 267 Trench III Plans

from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 267

Plate 267

Trench III Plans:

- XV. lviii. Errata: In hatching key, Plate xl Re-used should be Phase l Re-used an Phase liv Re-Used should be Phase lv Re-Used.

- XV.lix. Erraturm: In hatching key, horizontal lines of phase lix should be broken lines

- XVI.lx, lxi. Earratum: In caaption, PHASE XVI.xli should be PHASES XVI.lx and lxi.

- XVI.lxii.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Pl. 267 Trench III Plans

from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 267

Plate 267

Trench III Plans:

- XV. lviii. Errata: In hatching key, Plate xl Re-used should be Phase l Re-used an Phase liv Re-Used should be Phase lv Re-Used.

- XV.lix. Erraturm: In hatching key, horizontal lines of phase lix should be broken lines

- XVI.lx, lxi. Earratum: In caaption, PHASE XVI.xli should be PHASES XVI.lx and lxi.

- XVI.lxii.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

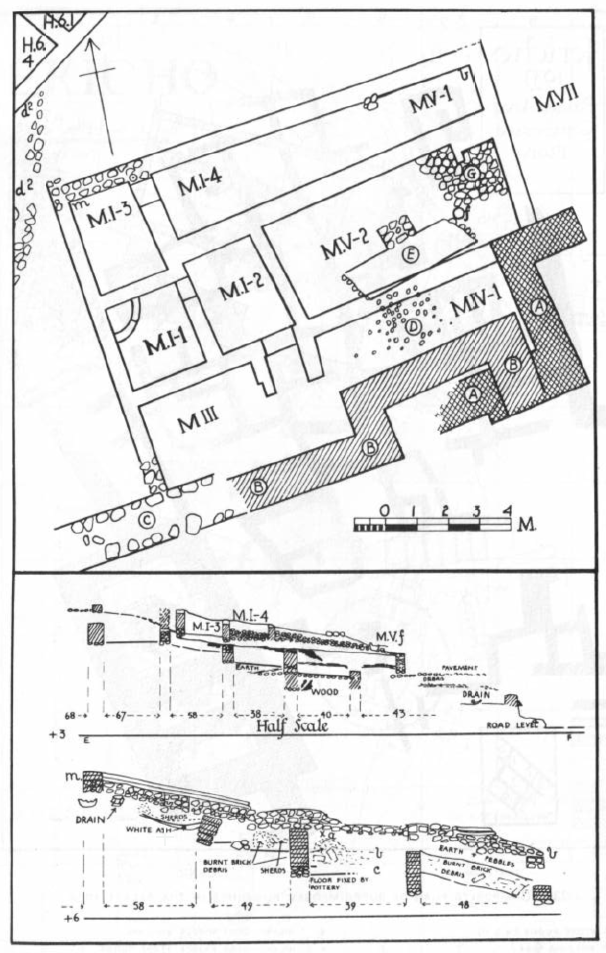

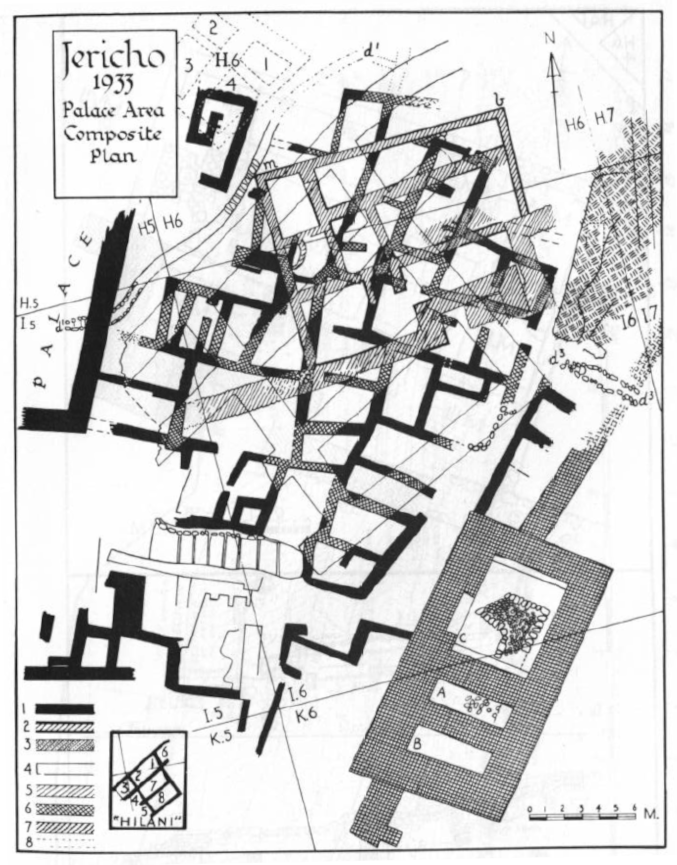

- Fig. 55 Middle Building

composite plan from Bienkowski (1986)

Figure 55

Figure 55

Middle Building area: composite plan (from Garstang 1934. pl.XIII)

- Palace Store-Rooms (MBII)

- Middle Building (LBA)

- Middle Building Over Palace Store-Rooms

- "Hilani" (E.I.A.I.)

- "Hilani" Over Middle Building

- "Hilani" Over Palace Store-Rooms

- "Hilani" Over Middle Building and Palace Store-Rooms

- House In Square H.6

Click on image to open in a new tab

Bienkowski (1986) - Fig. 56 Middle Building

plan and sections from Bienkowski (1986)

- Fig. 55 Middle Building

composite plan from Bienkowski (1986)

Figure 55

Figure 55

Middle Building area: composite plan (from Garstang 1934. pl.XIII)

- Palace Store-Rooms (MBII)

- Middle Building (LBA)

- Middle Building Over Palace Store-Rooms

- "Hilani" (E.I.A.I.)

- "Hilani" Over Middle Building

- "Hilani" Over Palace Store-Rooms

- "Hilani" Over Middle Building and Palace Store-Rooms

- House In Square H.6

Click on image to open in a new tab

Bienkowski (1986) - Fig. 56 Middle Building

plan and sections from Bienkowski (1986)

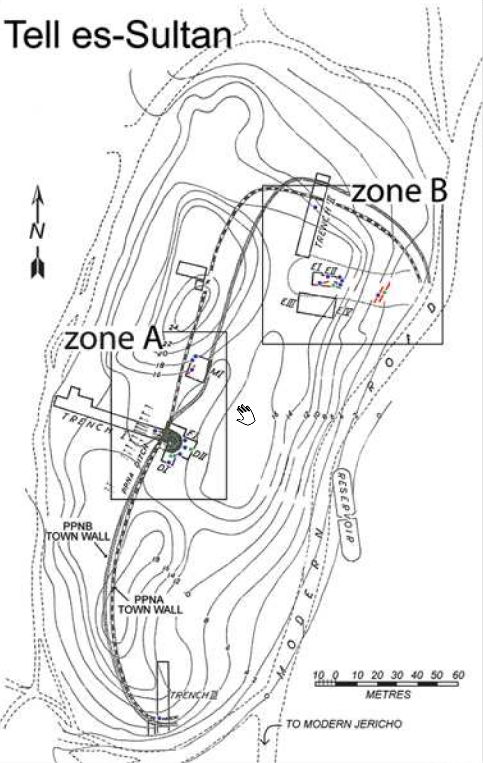

- Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone A at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

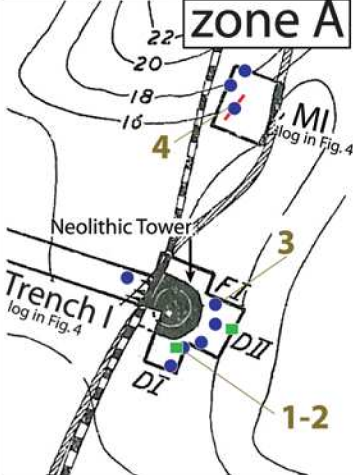

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone A between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone B at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone B between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Entire Tell at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan (Entire Tell) between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Legend for Map

of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Legend for Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone A at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone A between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

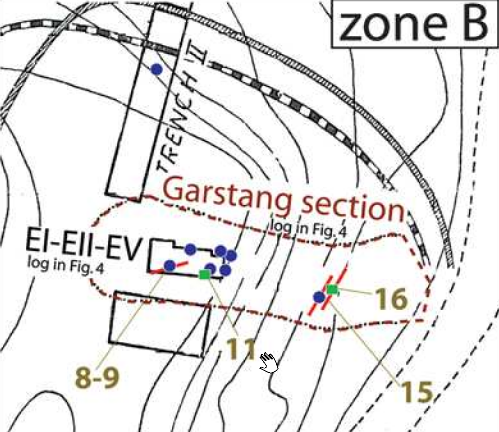

effects in Zone B at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone B between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Entire Tell at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan (Entire Tell) between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Legend for Map

of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Legend for Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

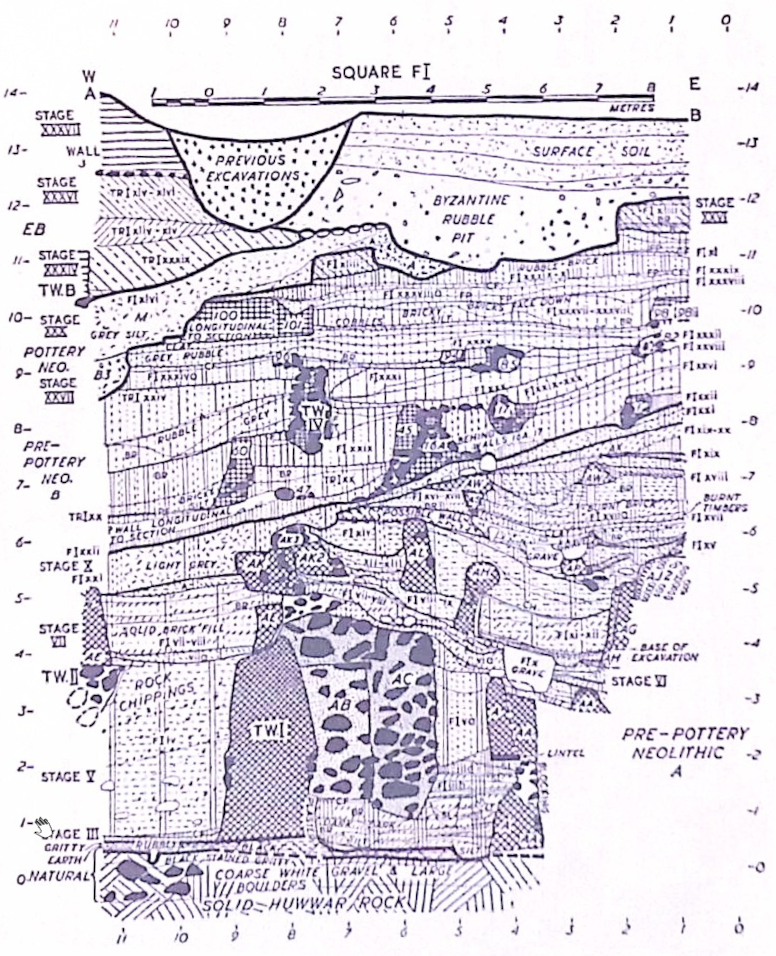

- Fig. 4 Section of Trench 1 from Kenyon (1957)

- Pl. 236 Section A-B of

Square FI from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

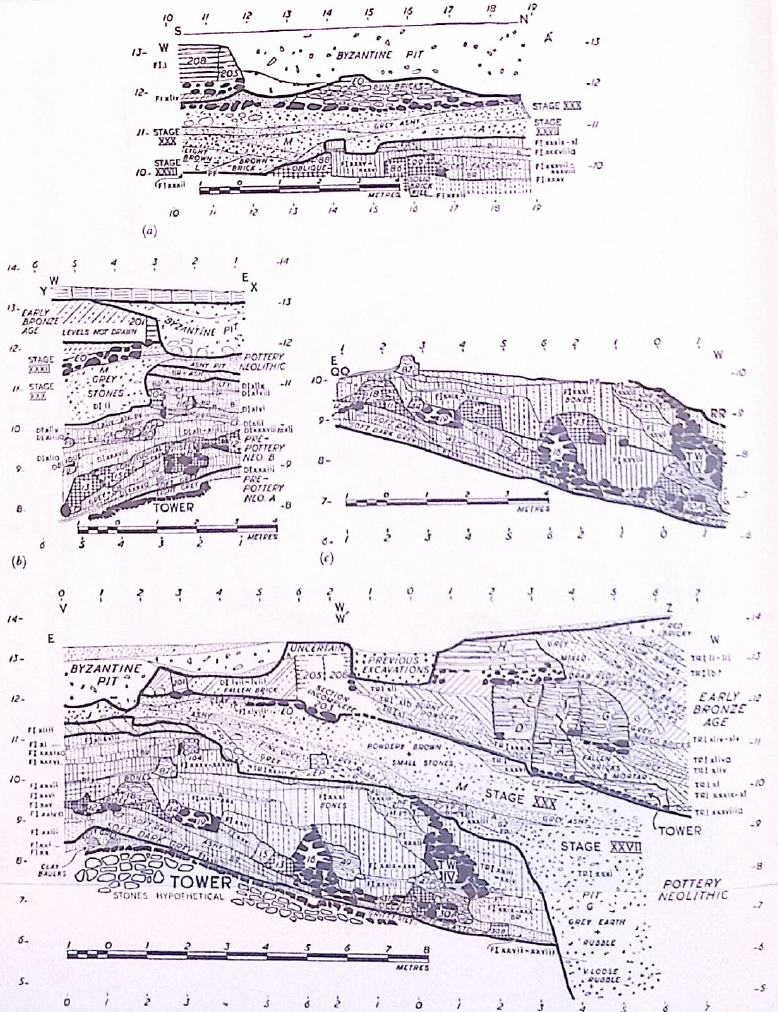

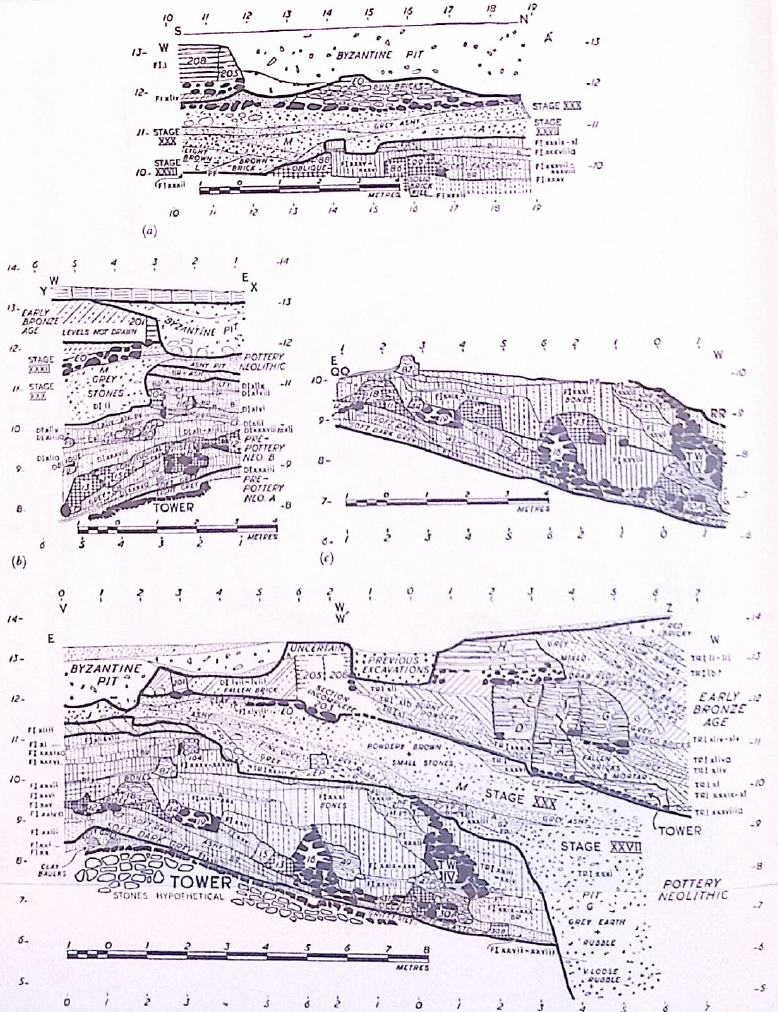

- Pl. 240 Tr.I, FI, DI

Sections from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

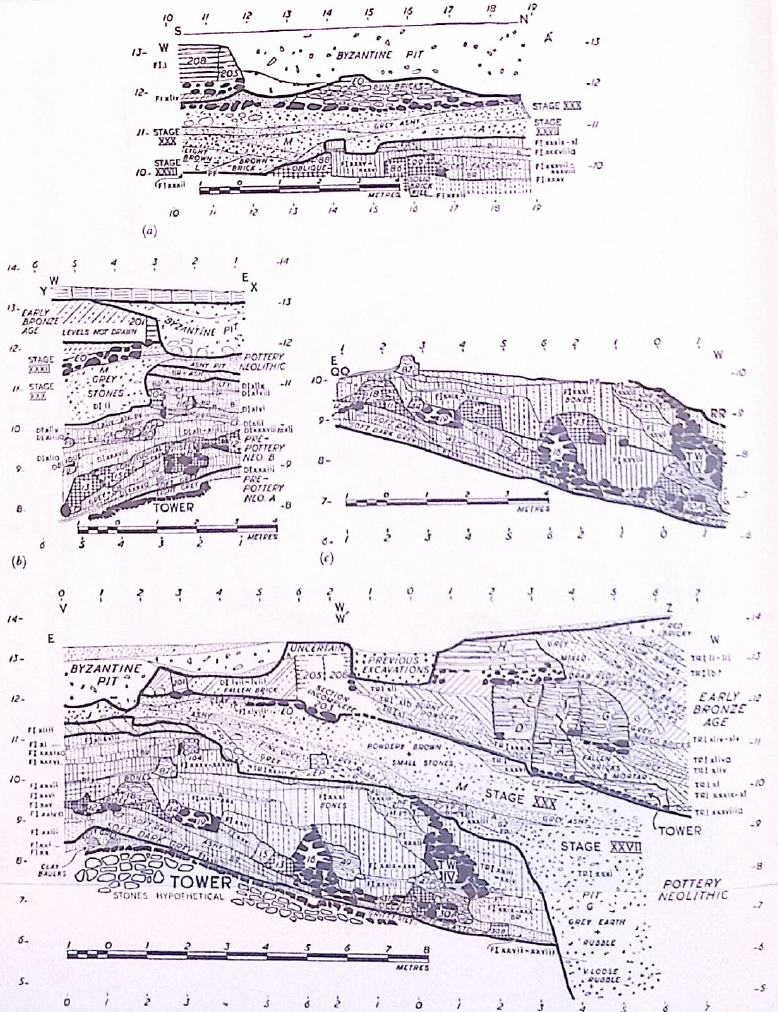

Plate 240

Tr.I, FI, DI. Sections:

- Fl. Section W-A'. Erratum: Phase hatched xlix, betweeen 10.25 m. and 11.80 m. N., 11.80 m. and 12 m. H., should be phase xlixa and is incorrectly hatches

- Dl. Section X-Y

- Fl. Section QQ-RR. Erratum: Phase FI.xxvi should be FI.xxva

- FI, Tr.I. Section V-W, W'-Z. Errata: Phase FI.xxvi, between 3.90 m. and 4.90 m. W., 8.50 m. H., should be FI.xxva. Wall numbered 205 should be 208 and Wall 208 should be 205

Click on image to open in a new tab

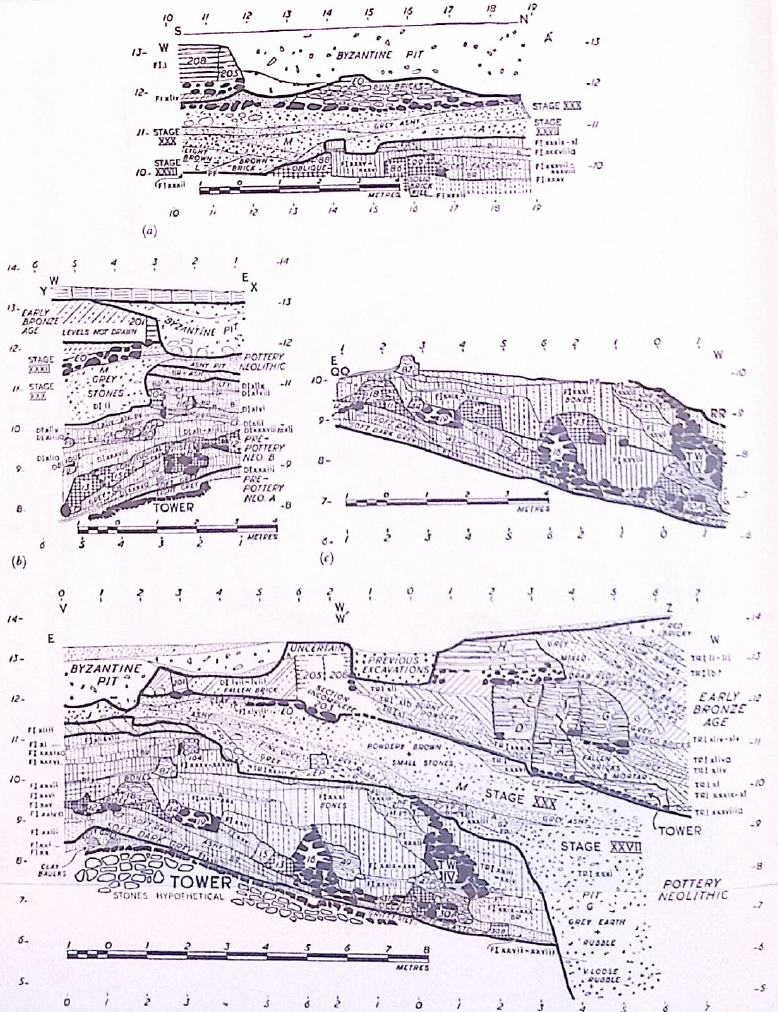

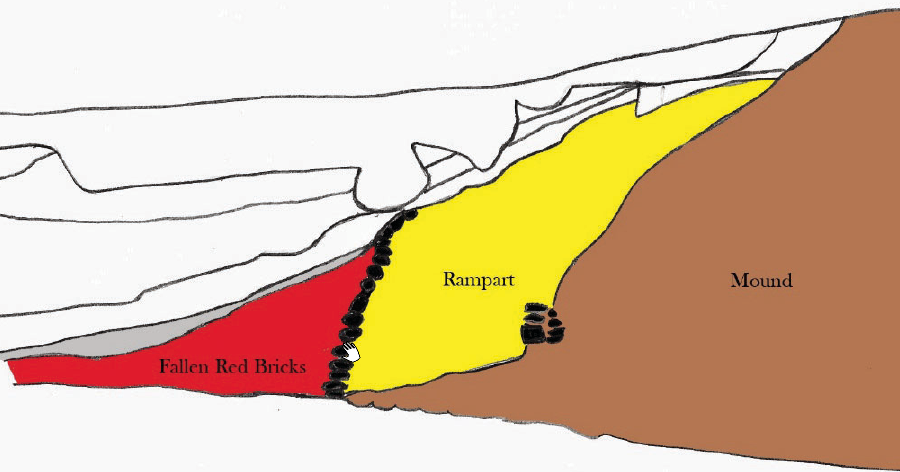

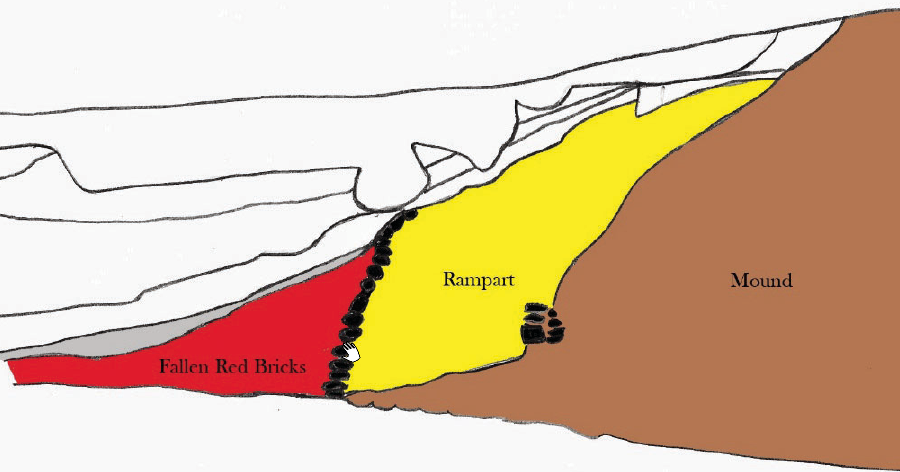

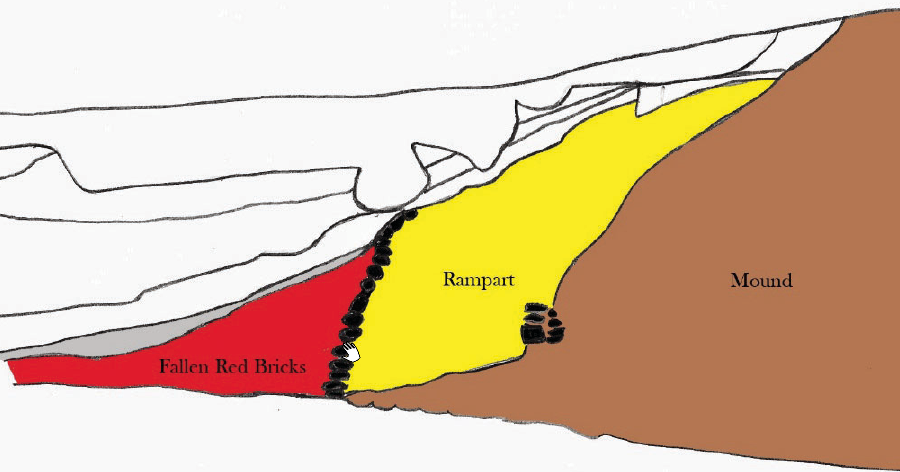

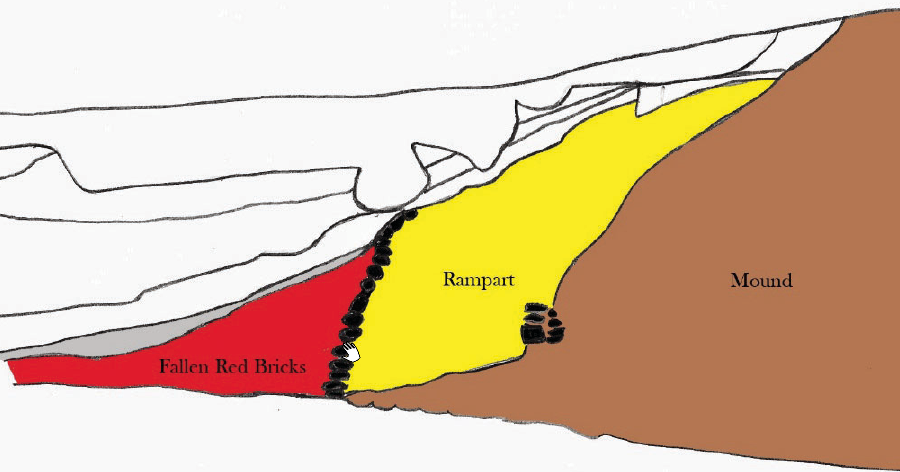

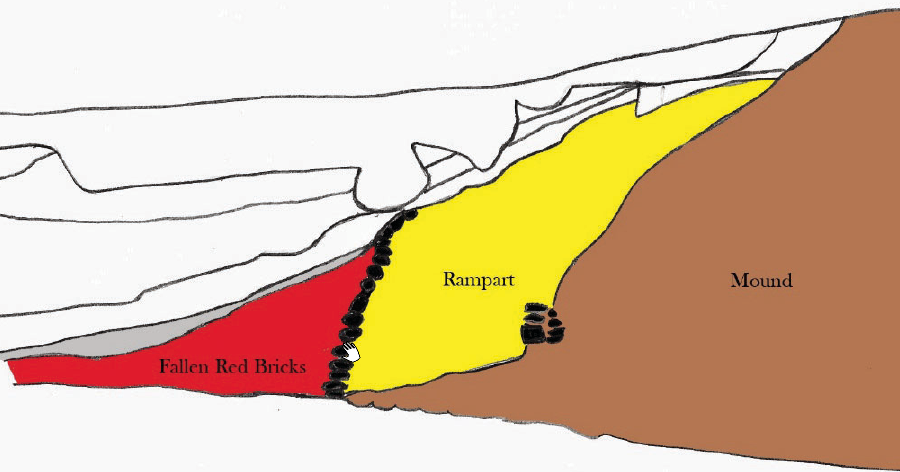

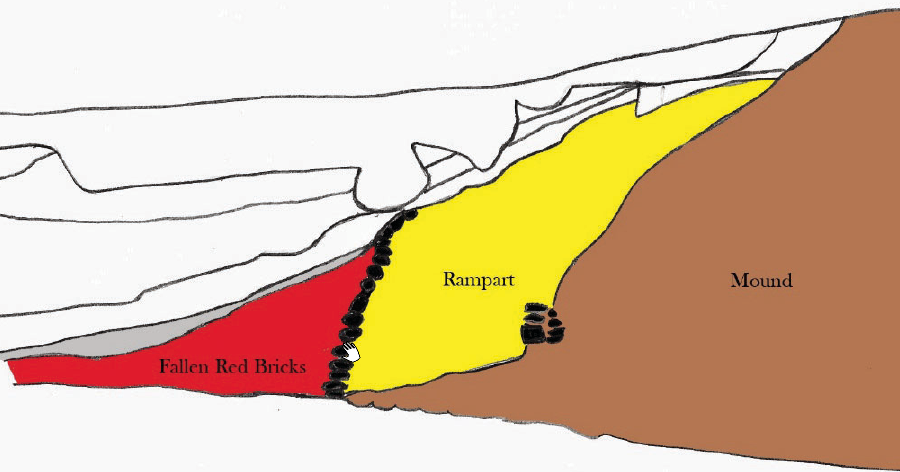

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Fig. 2 Cross section of

Trench I from Kennedy (2023)

Figure 2

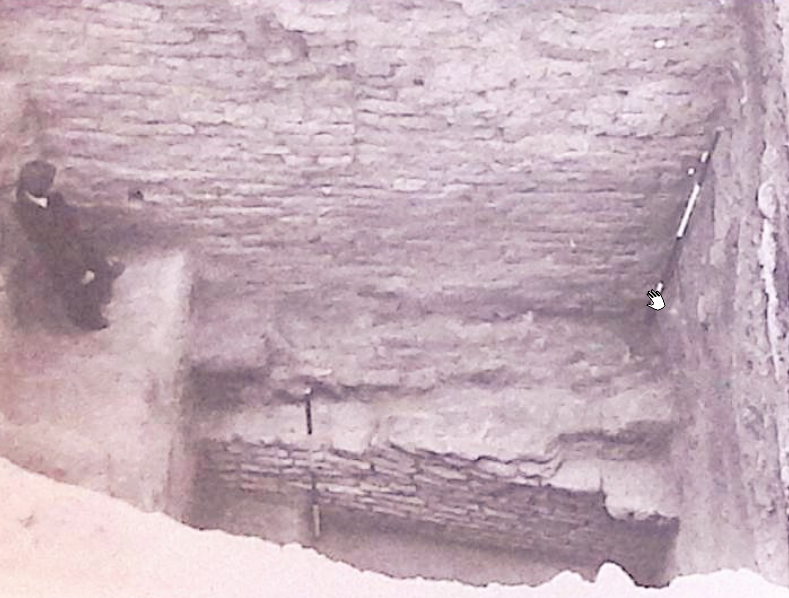

Figure 2

Cross section of Trench I showing the Jericho outer city wall built in Middle Bronze III. The pile of fallen mudbricks in the form of a ramp in front of the stone retaining wall originally comprised a mudbrick wall atop the stone retaining wall.

click on image to open in a new tab

Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 4 Section of Trench 1 from Kenyon (1957)

- Pl. 236 Section A-B of

Square FI from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Pl. 240 Tr.I, FI, DI

Sections from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 240

Tr.I, FI, DI. Sections:

- Fl. Section W-A'. Erratum: Phase hatched xlix, betweeen 10.25 m. and 11.80 m. N., 11.80 m. and 12 m. H., should be phase xlixa and is incorrectly hatches

- Dl. Section X-Y

- Fl. Section QQ-RR. Erratum: Phase FI.xxvi should be FI.xxva

- FI, Tr.I. Section V-W, W'-Z. Errata: Phase FI.xxvi, between 3.90 m. and 4.90 m. W., 8.50 m. H., should be FI.xxva. Wall numbered 205 should be 208 and Wall 208 should be 205

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Fig. 2 Cross section of

Trench I from Kennedy (2023)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Cross section of Trench I showing the Jericho outer city wall built in Middle Bronze III. The pile of fallen mudbricks in the form of a ramp in front of the stone retaining wall originally comprised a mudbrick wall atop the stone retaining wall.

click on image to open in a new tab

Kennedy (2023)

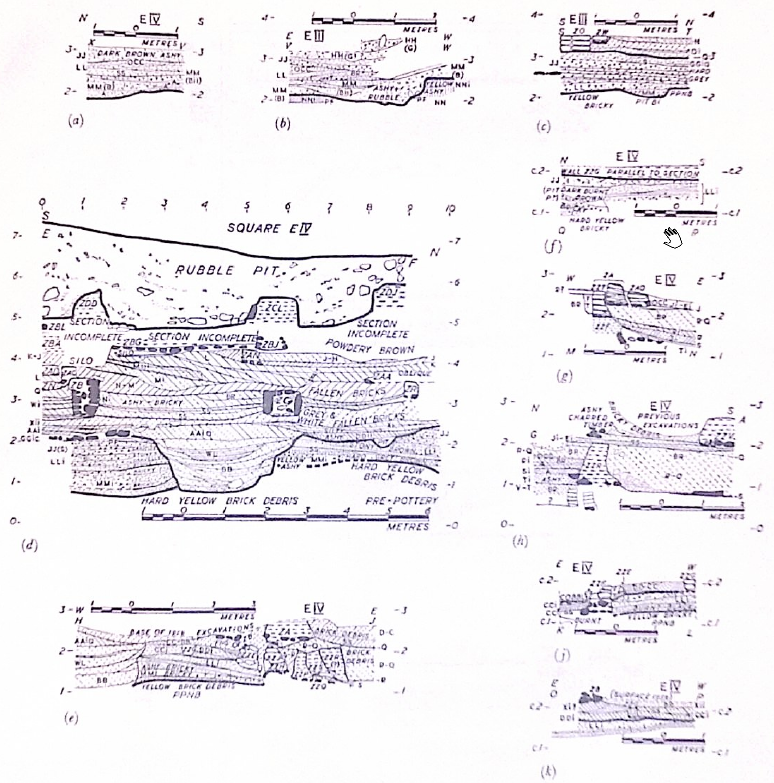

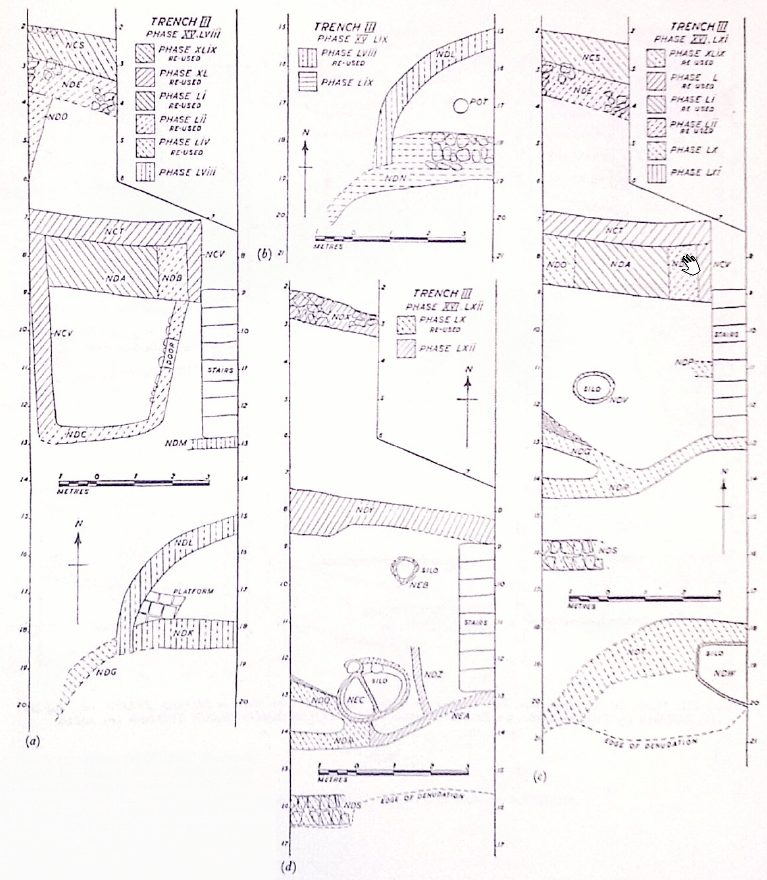

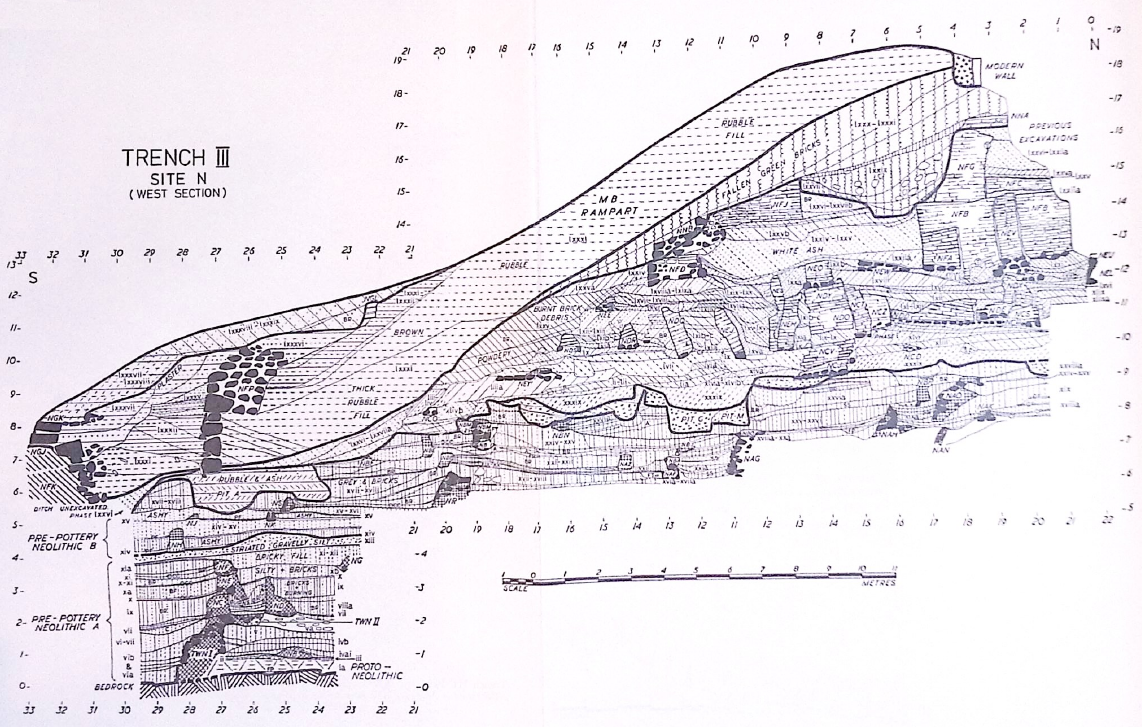

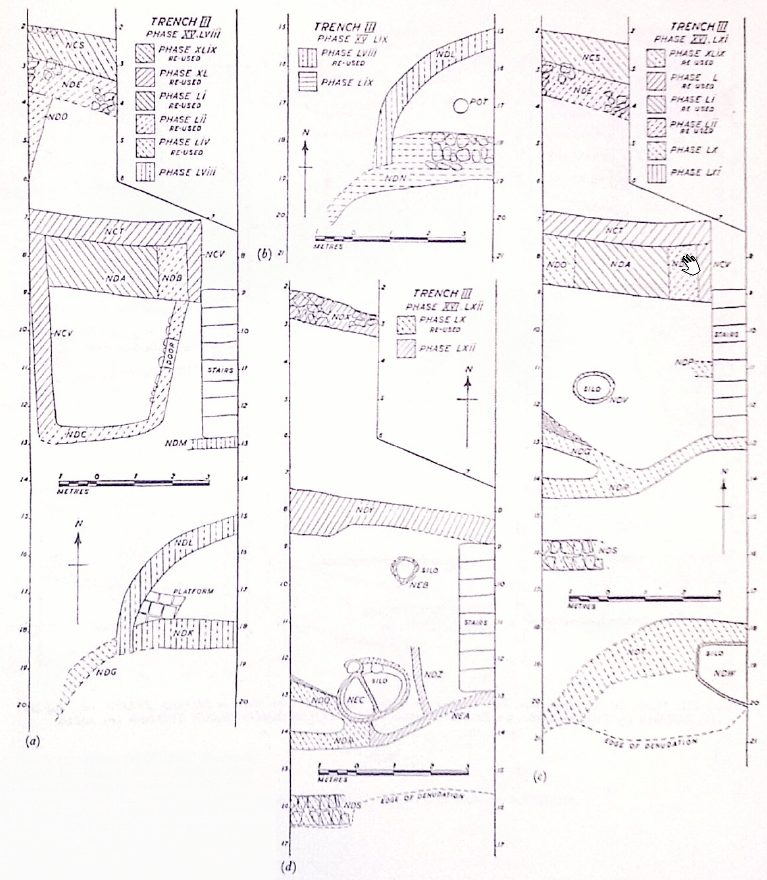

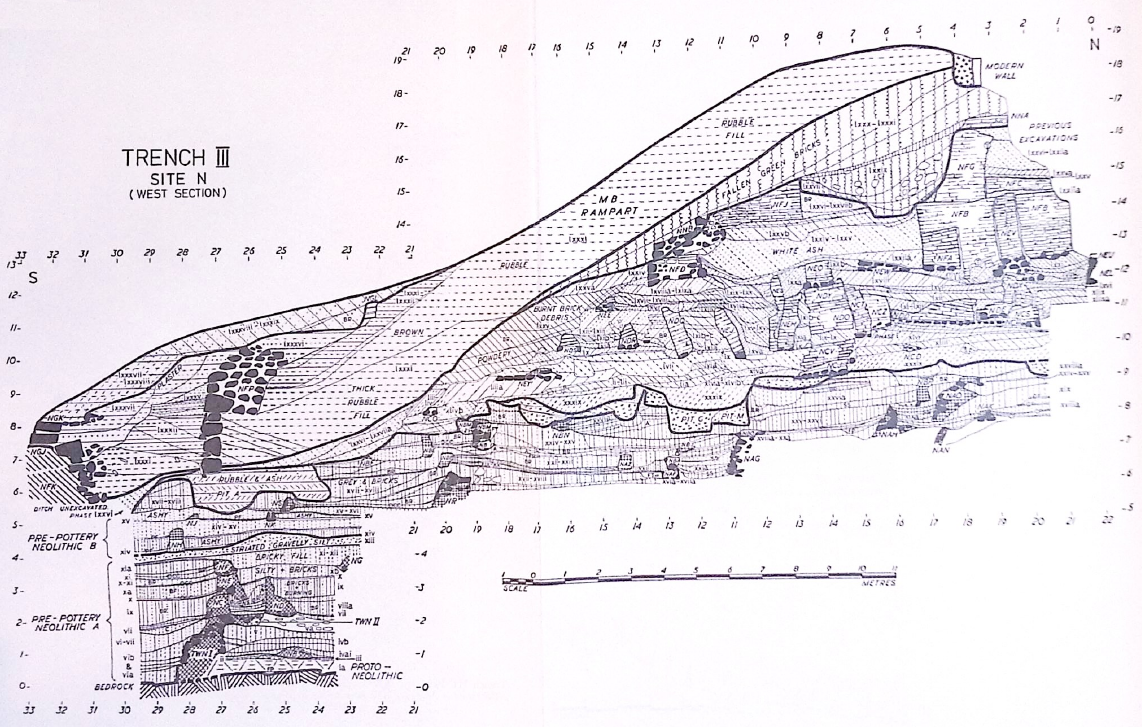

- Plate 273 West Section of

Trench III from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 273

Plate 273

Trench III. West Section. Errata: Metre numbers 0-12 S. at bottom N. end of trench incorrectly numbered 22-12. Lettering of Wall NEN, betweeen 1.60 m. and 2.20 m. S., 11.70 m. H., omitted. Phase lxxvi-lxxviia, between c. 1.50 m. and 3.50 m. S., 15 m. and 16.30 m. H., incorrectly numbered lxxvi-lxxiia.

Click on image to open in a new tab

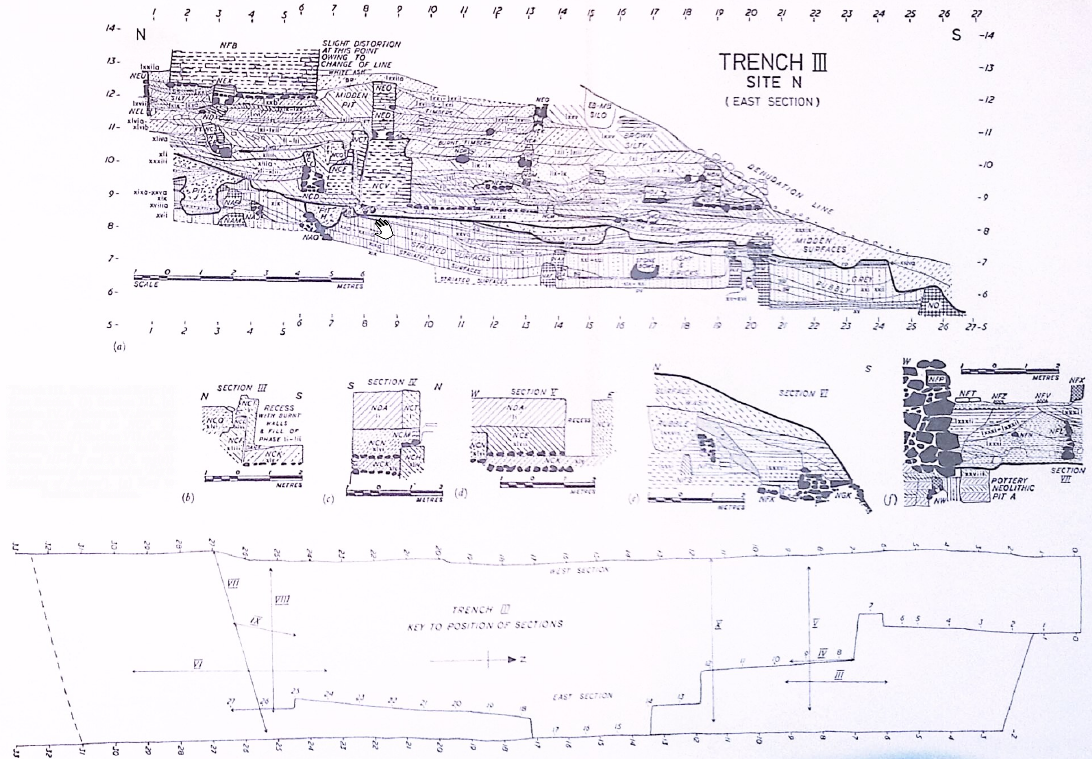

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Plate 274 East Section of

Trench III from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 274

Plate 274

Trench III. Sections and Key.

- East Section

- Section III

- Section IV

- Section V. Erratum: Wall NCE should be NCP.

- Section VI

- Section VII (N.B. Hatching used to deliniate walls on Sections III-VII and X (Pl. 275(c)) is independent of scheme used on 'Key to Hatching of Sections')

- Key to Positi0n of Sections

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Plate 273 West Section of

Trench III from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 273

Plate 273

Trench III. West Section. Errata: Metre numbers 0-12 S. at bottom N. end of trench incorrectly numbered 22-12. Lettering of Wall NEN, betweeen 1.60 m. and 2.20 m. S., 11.70 m. H., omitted. Phase lxxvi-lxxviia, between c. 1.50 m. and 3.50 m. S., 15 m. and 16.30 m. H., incorrectly numbered lxxvi-lxxiia.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Plate 274 East Section of

Trench III from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 274

Plate 274

Trench III. Sections and Key.

- East Section

- Section III

- Section IV

- Section V. Erratum: Wall NCE should be NCP.

- Section VI

- Section VII (N.B. Hatching used to deliniate walls on Sections III-VII and X (Pl. 275(c)) is independent of scheme used on 'Key to Hatching of Sections')

- Key to Positi0n of Sections

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

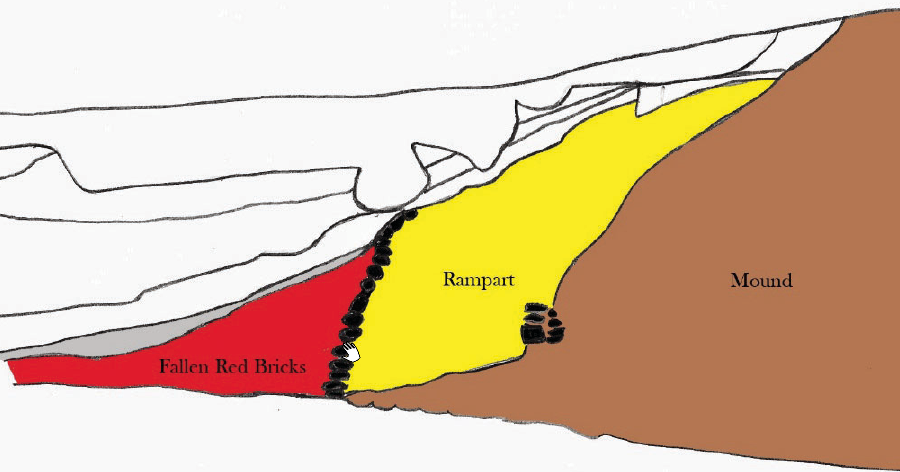

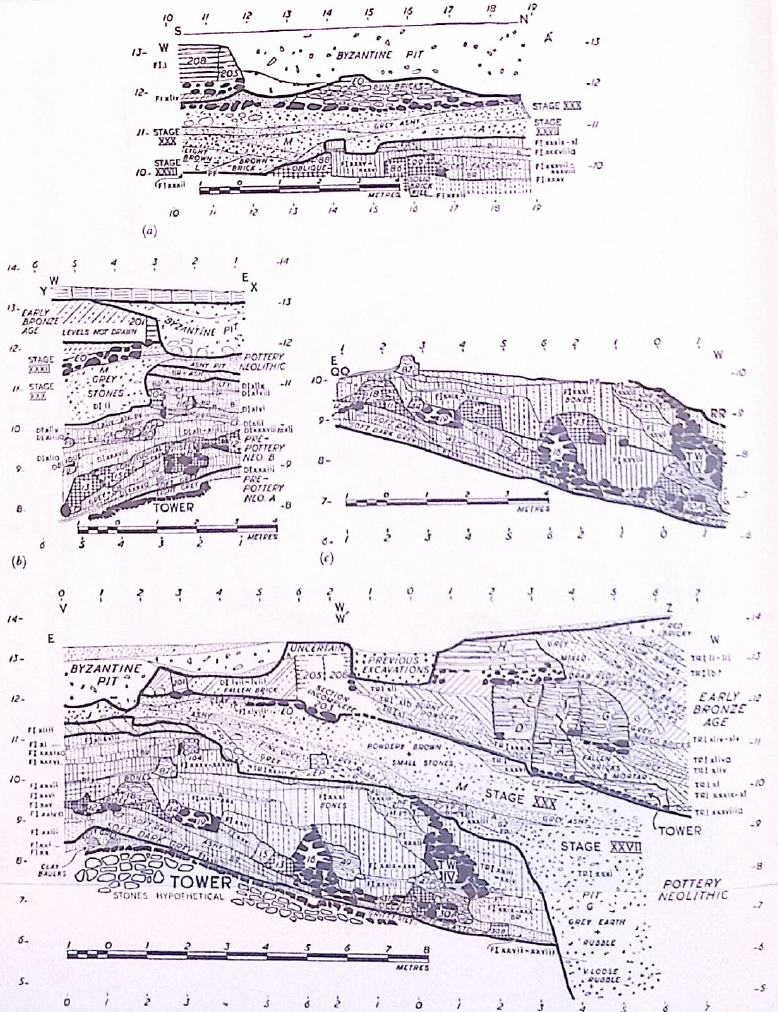

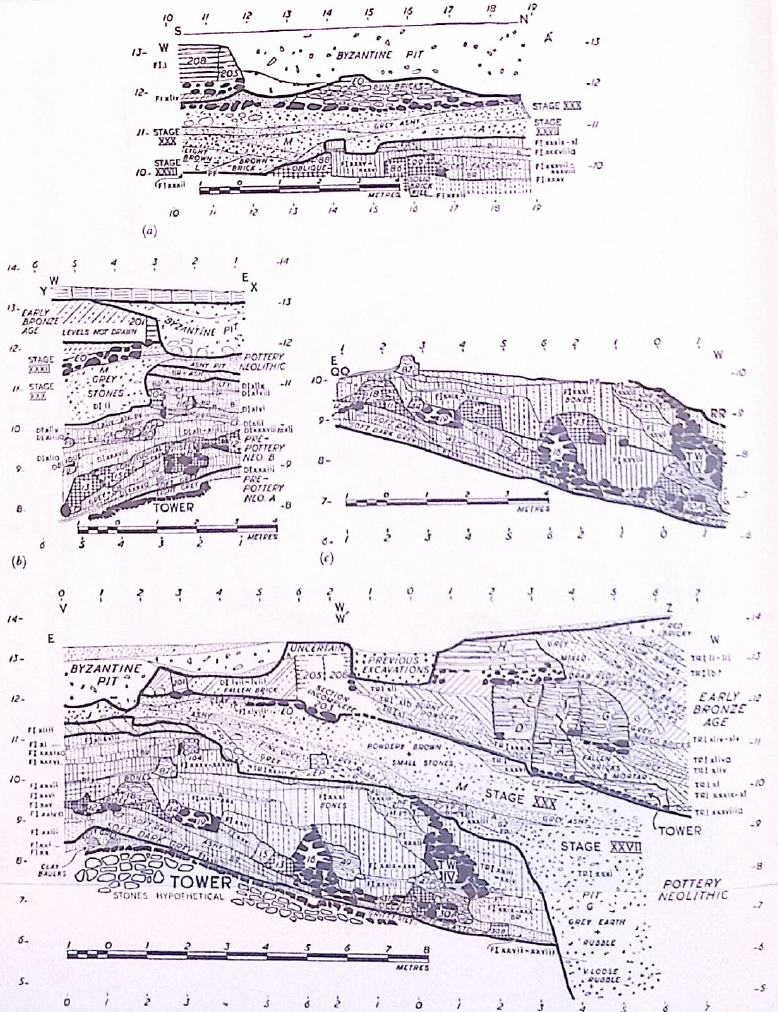

- Fig. 4 Archaeoseismic

stratigraphic sections from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Archaeoseismic stratigraphic sections modified from Garstang and Garstang (1948) and Kenyon (1981). Dashed squares in Garstang’s section are the approximate projections of Kenyon’s excavations both from zone A (logs in the inset) and zone B. The time— space relations between the layers and the observed coseismic effects (point numbers as in Figure 2 and Table 2) are illustrated. Horizons of the seismic shaking events recognized within the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period are marked by stars.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Plate VI Section

through the Excavated Area in the Northeast Corner from Garstang and Garstang (1948)

- Fig. 4 Archaeoseismic

stratigraphic sections from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Archaeoseismic stratigraphic sections modified from Garstang and Garstang (1948) and Kenyon (1981). Dashed squares in Garstang’s section are the approximate projections of Kenyon’s excavations both from zone A (logs in the inset) and zone B. The time— space relations between the layers and the observed coseismic effects (point numbers as in Figure 2 and Table 2) are illustrated. Horizons of the seismic shaking events recognized within the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period are marked by stars.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Plate VI Section

through the Excavated Area in the Northeast Corner from Garstang and Garstang (1948)

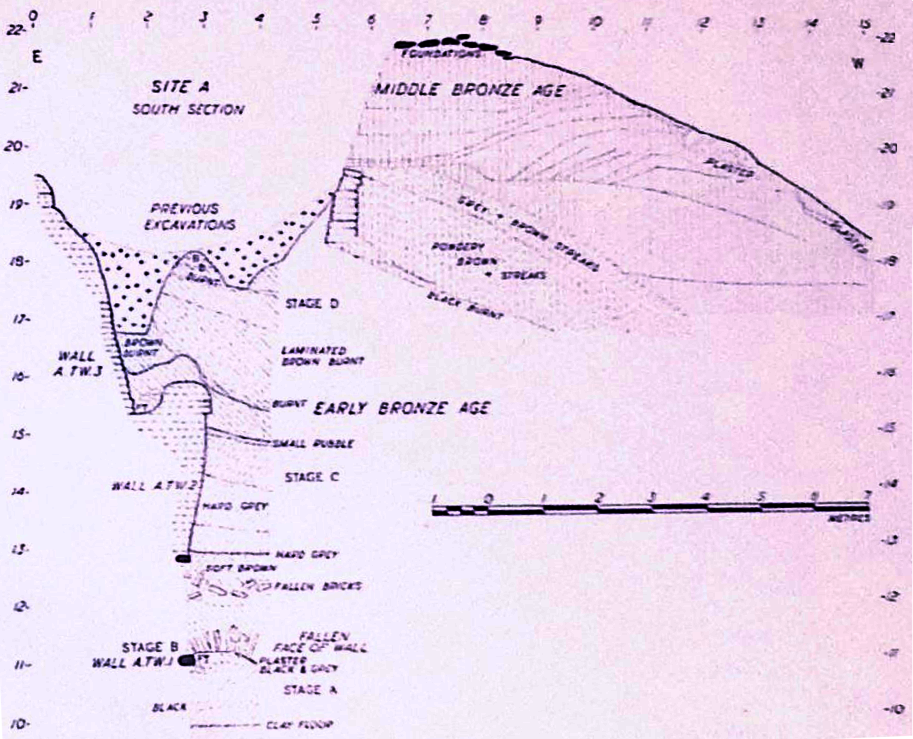

- Pl. 343a South Section of Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Pl. 343a South Section of Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

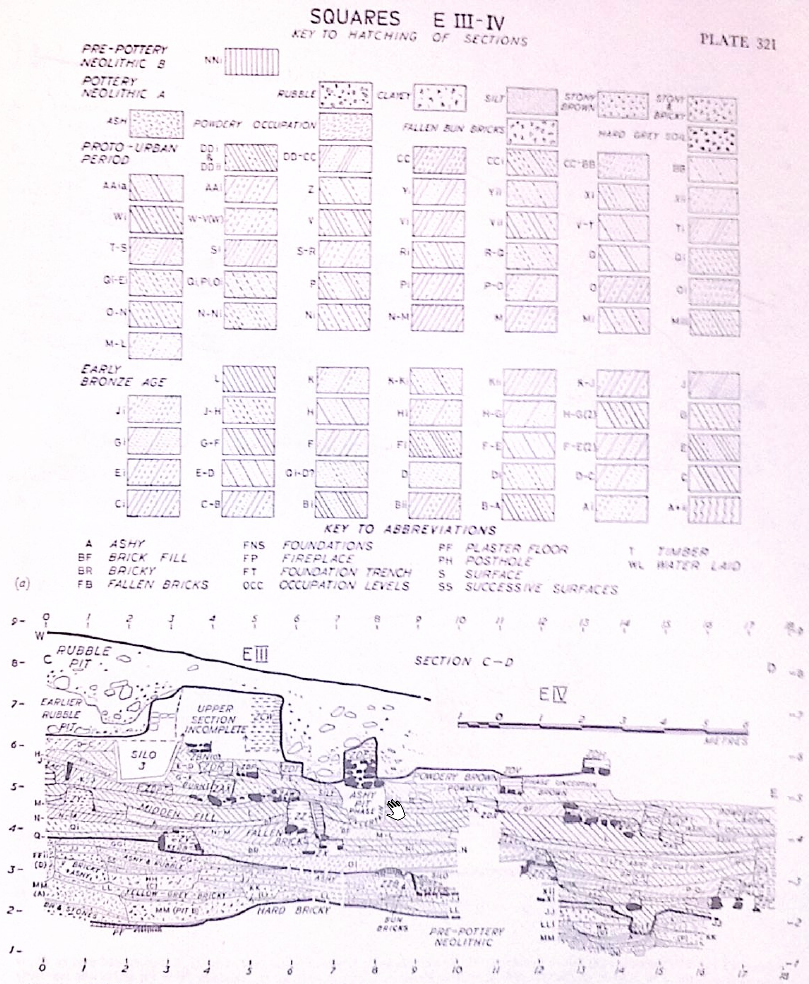

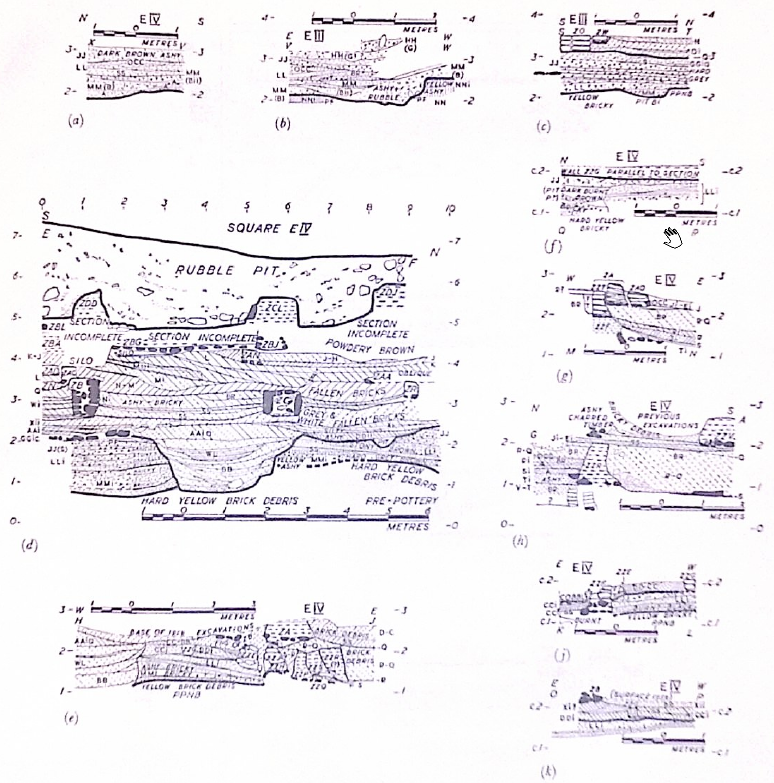

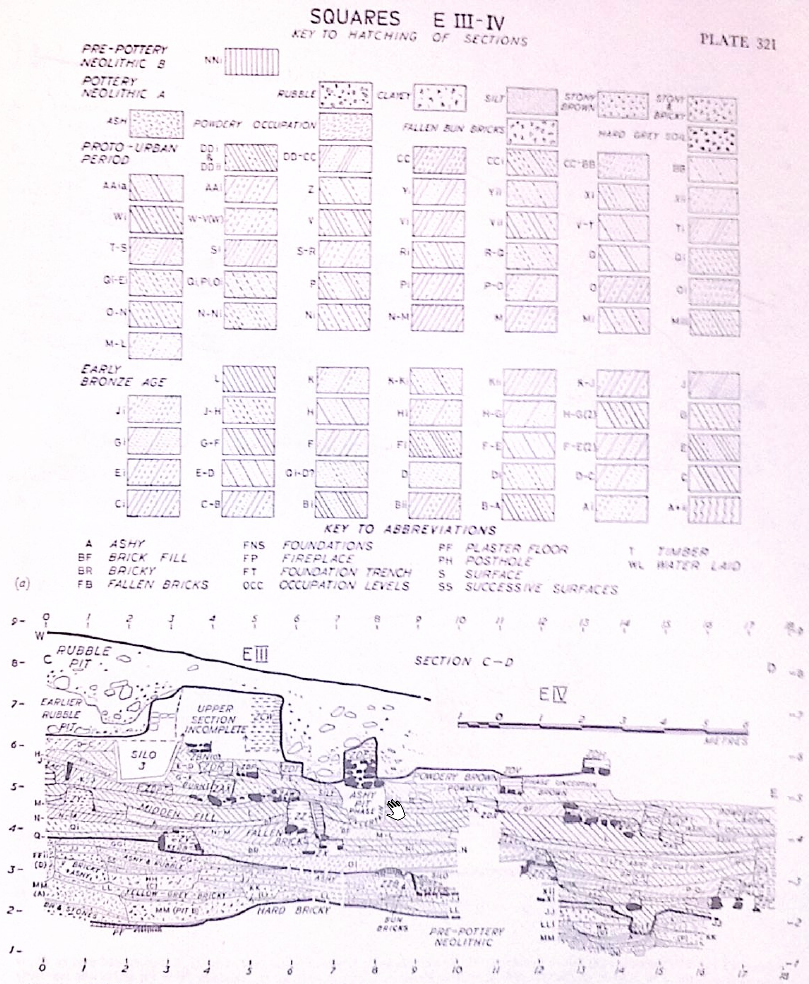

- Pl. 321 Section from Squares

EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

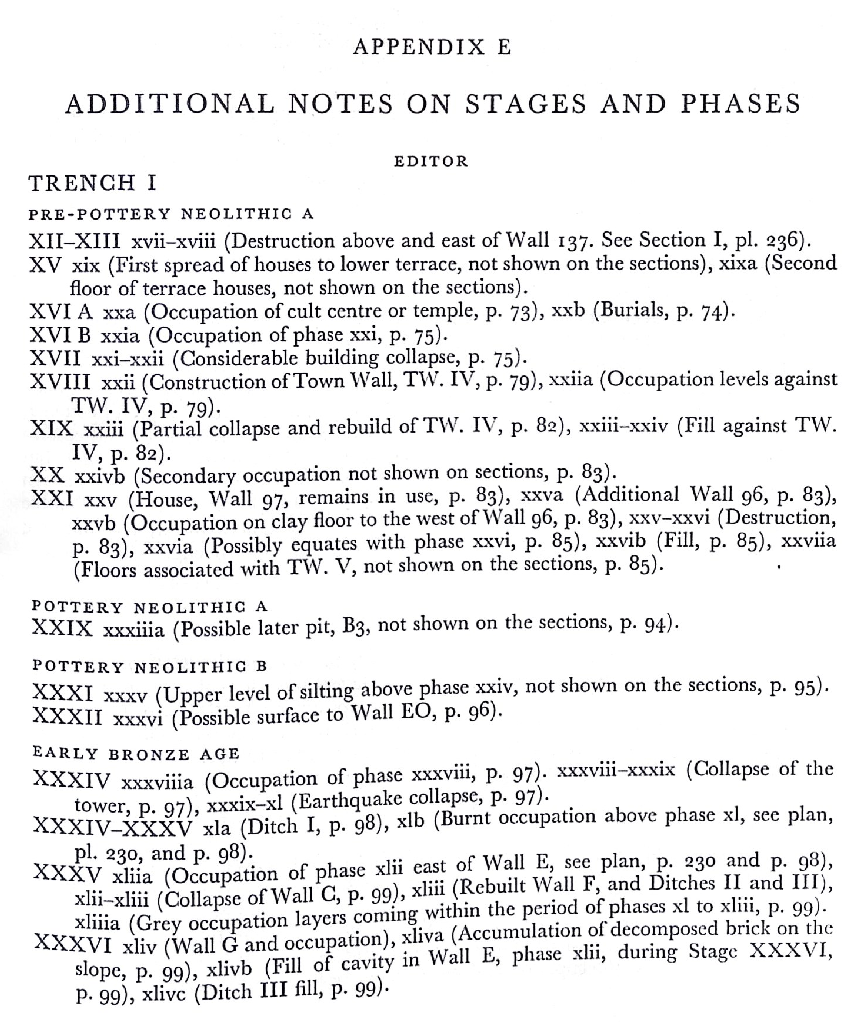

Plate 321

Squares EIII-IV, Keys and Section

- Key to Hatching of Sections and Key to Abbreviations. Errata: Phase Ji should be broken and three dotted diagonal lines. Hatching lettered phase Qi–D? should be E-D?. Hatching duplicated on sections for Phases Vi and Kii, Phases V–T and M, Phases R–Q and Di, Phases Pi and Ci.

- North Section C–D. Errata: Broken Lettering of Pit Bii, between c. 2 m. and 4 m. E., 2.3 m. n., H., omitted. Phase lettered GGi, between 0.25 m. and 6 m. E., should be GGib. Hatching of Phase Ji, between c. 15.30 m. and 17/60 m. E., 4 m. H., incorrect.

Click on image to open in a new tab

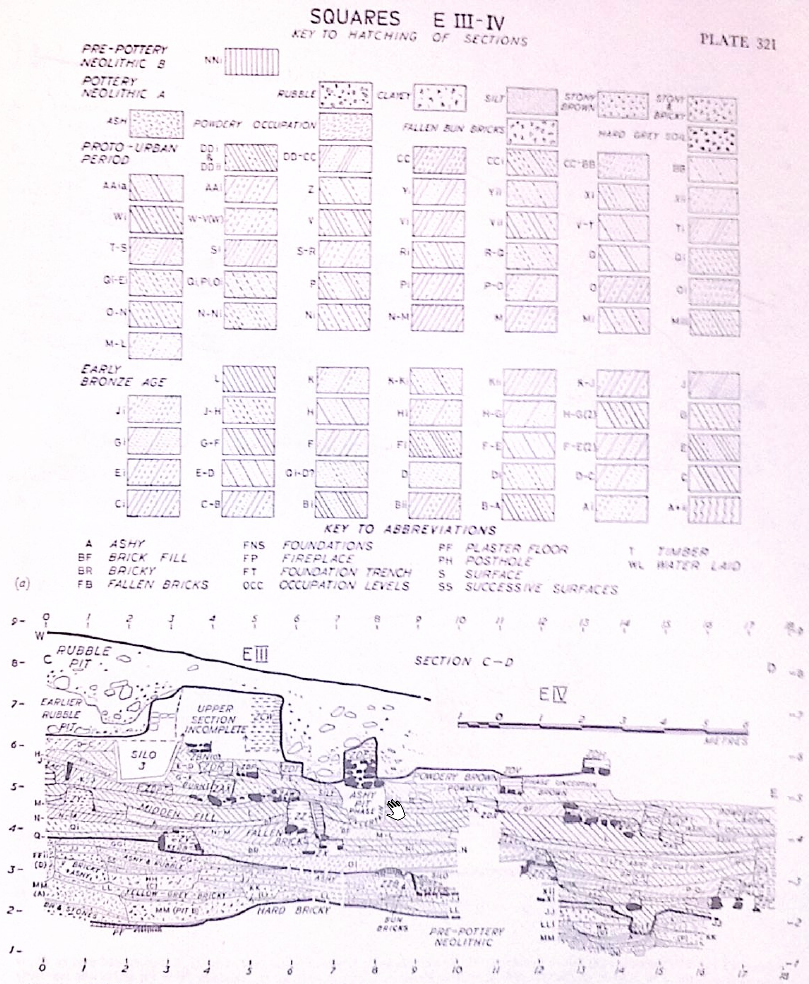

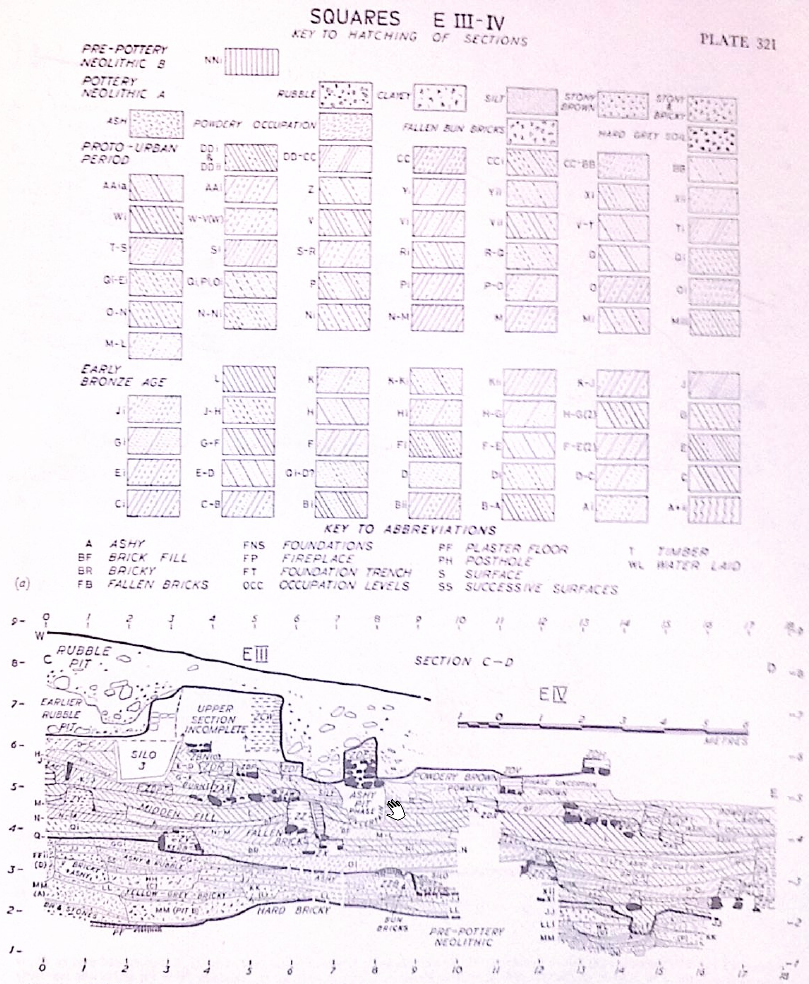

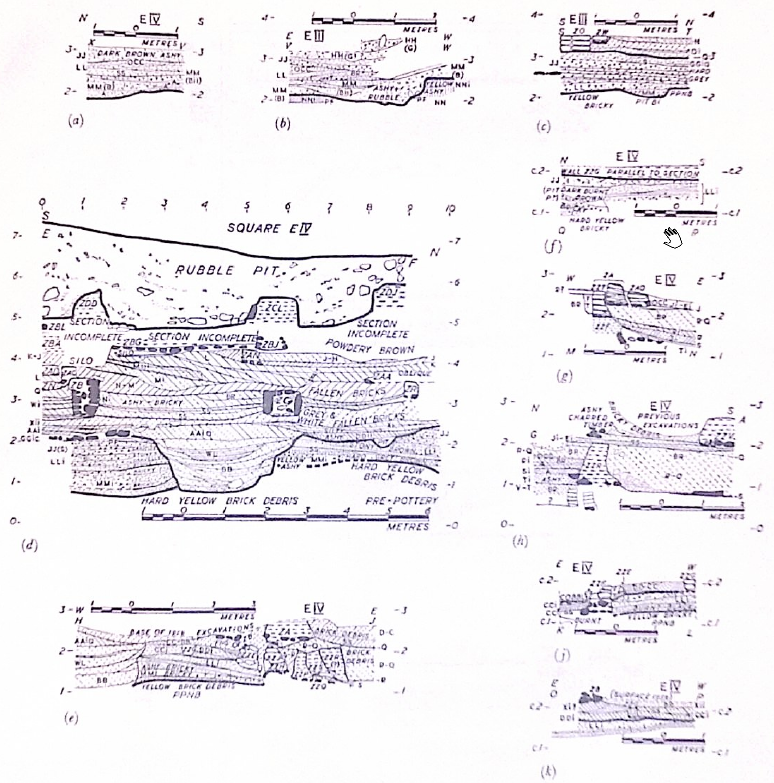

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Pl. 323 Sections from Squares

EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 323

Squares EIII-IV, Sections:

- Section X–V. Erratum: Location square, EIV, should be EIII.

- Section V-W

- Section S–T

- Section E–F. Errata: Phase Hatched M Mi, between 5.75 m. and 9.89 m. N, 1.50 m. H., should be M Mii. slight error on the hatching of Phase Miii between 3.50 m. and 4 m.,N., 3.75 m. H.

- Section H–J. Erratum: Phase Q, between 2.10 m and 2.60 m H. on east of section, is incorrectly hatched and lettered and should be altered to Phases Qi-Ei

- Section Q–R

- Section N–M. Erratum: Phases Ji-Ei at c. 2.20 m. H. should be Qi-Ei

- Section G–A. Erratum: Phases Ji-Ei at c. 2.10 m. H. should be Qi-Ei

- Section K–L

- Section O–P

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Pl. 321 Section from Squares

EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 321

Squares EIII-IV, Keys and Section

- Key to Hatching of Sections and Key to Abbreviations. Errata: Phase Ji should be broken and three dotted diagonal lines. Hatching lettered phase Qi–D? should be E-D?. Hatching duplicated on sections for Phases Vi and Kii, Phases V–T and M, Phases R–Q and Di, Phases Pi and Ci.

- North Section C–D. Errata: Broken Lettering of Pit Bii, between c. 2 m. and 4 m. E., 2.3 m. n., H., omitted. Phase lettered GGi, between 0.25 m. and 6 m. E., should be GGib. Hatching of Phase Ji, between c. 15.30 m. and 17/60 m. E., 4 m. H., incorrect.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2) - Pl. 323 Sections from Squares

EIII-IV from Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

Plate 323

Squares EIII-IV, Sections:

- Section X–V. Erratum: Location square, EIV, should be EIII.

- Section V-W

- Section S–T

- Section E–F. Errata: Phase Hatched M Mi, between 5.75 m. and 9.89 m. N, 1.50 m. H., should be M Mii. slight error on the hatching of Phase Miii between 3.50 m. and 4 m.,N., 3.75 m. H.

- Section H–J. Erratum: Phase Q, between 2.10 m and 2.60 m H. on east of section, is incorrectly hatched and lettered and should be altered to Phases Qi-Ei

- Section Q–R

- Section N–M. Erratum: Phases Ji-Ei at c. 2.20 m. H. should be Qi-Ei

- Section G–A. Erratum: Phases Ji-Ei at c. 2.10 m. H. should be Qi-Ei

- Section K–L

- Section O–P

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon et al. (1981 Part 2)

- Fig. 22 Section of the

tumbled down EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 22 Section of the

tumbled down EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

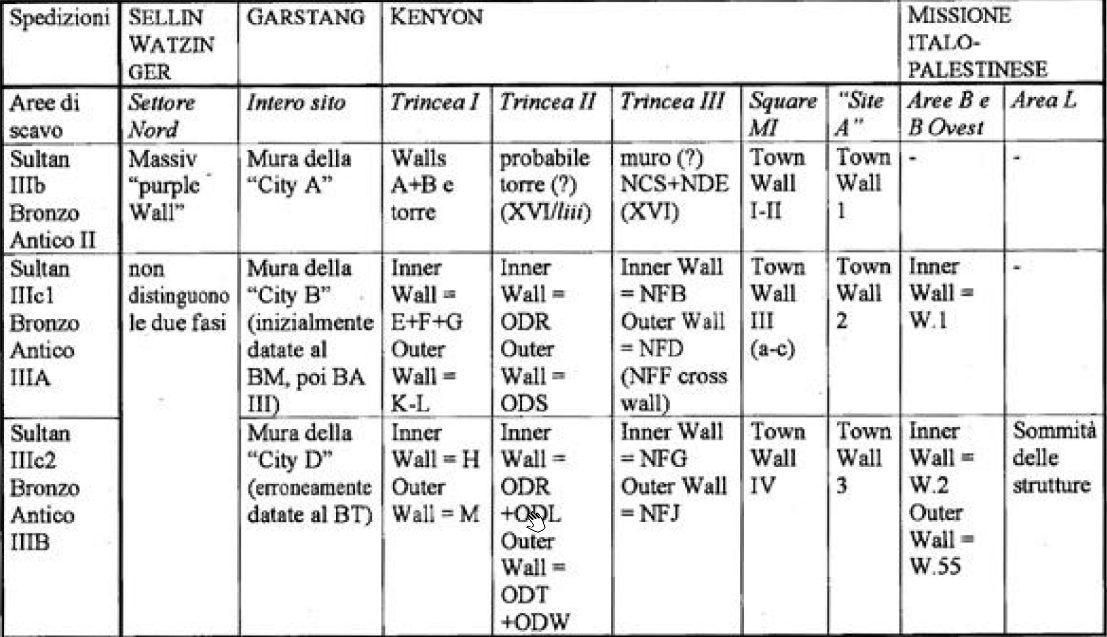

| Excavation phase | Sellin & Watzinger | Garstang | Kenyon | Italo-Palestinian Mission | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North sector | Whole site | Trench I | Trench II | Trench III | Square M | "Site A" | Areas B & B West | Area L | |

| Sultan IIIb – Early Bronze II | Massive “purple Wall” | Wall of “City A” | Walls A + B and tower |

probable tower (?) (XVI/III) |

wall (?) NCS + NDE (XVI) |

Town Wall I–II | Town Wall 1 | – | – |

| Sultan IIIc1 – Early Bronze IIIA |

they do not distinguish the two phases |

Wall of “City B” (initially dated to MB, later to EB III) |

Inner Wall = E + F + G Outer Wall = K – L |

Inner Wall = ODR Outer Wall = ODS |

Inner Wall = NFB Outer Wall = NFD (NFF cross wall) |

Town Wall III (a–c) | Town Wall 2 | Inner Wall = W.1 | – |

| Sultan IIIc2 – Early Bronze IIIB | – |

Wall of “City D” (erroneously dated to Late Bronze) |

Inner Wall = H Outer Wall = M |

Inner Wall = ODR + ODL Outer Wall = ODT + ODW |

Inner Wall = NFG Outer Wall = NFJ |

Town Wall IV | Town Wall 3 |

Inner Wall = W.2 Outer Wall = W.55 |

tops of the structures |

- Fig. 1 Oblique Aerial View

of Tell es-Sultan from Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 3a Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(a) Black arrows point to fractures crossing the floor and the perimeter wall of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B houses. Original picture from Kenyon (1981).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3b Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 3c Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3c

Figure 3c

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(c) View from the top of a complete northward collapse of a wall, giving the illusion of a pavement. Original picture from Kenyon (1981).

click on image to open in a new tab

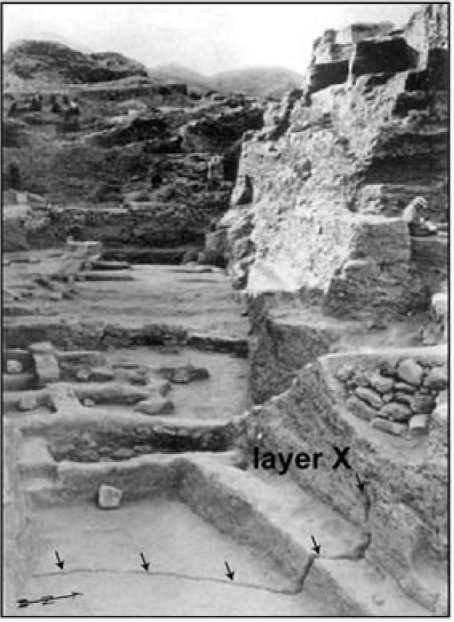

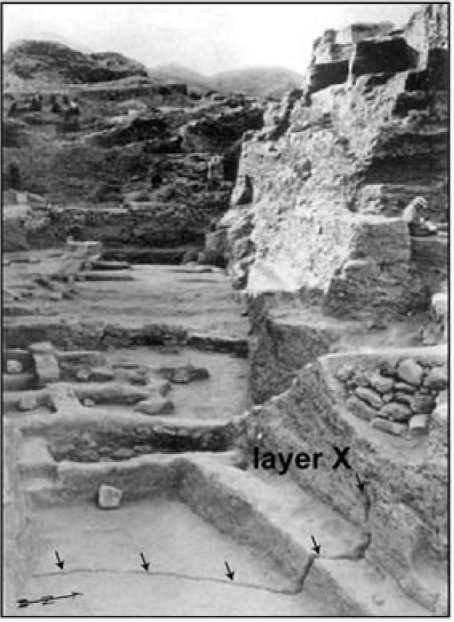

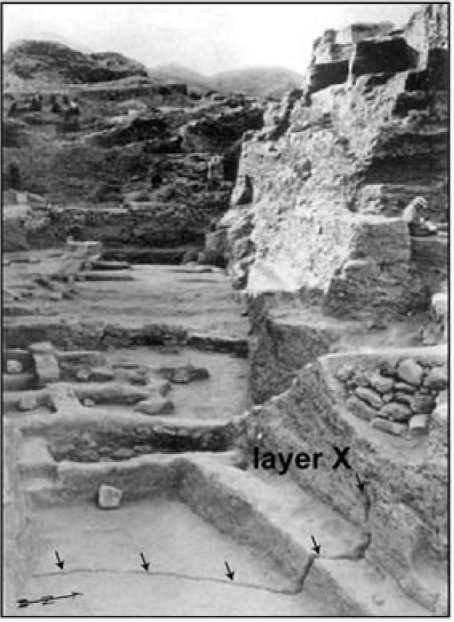

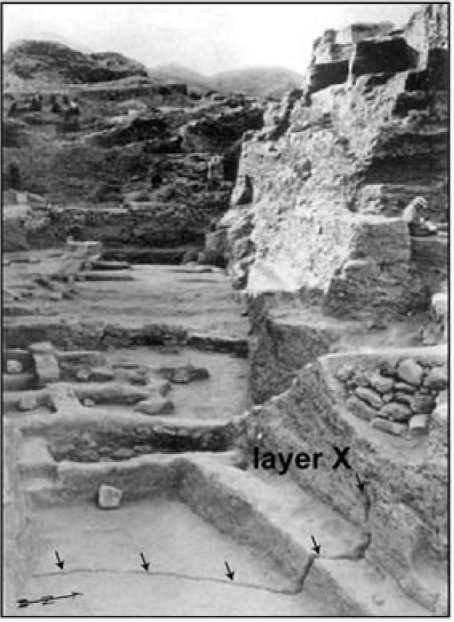

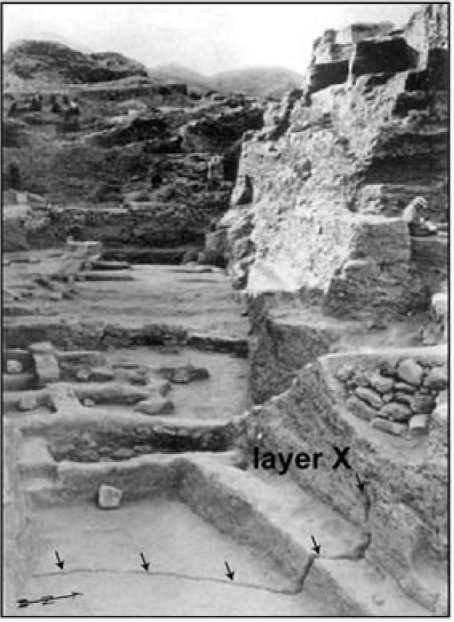

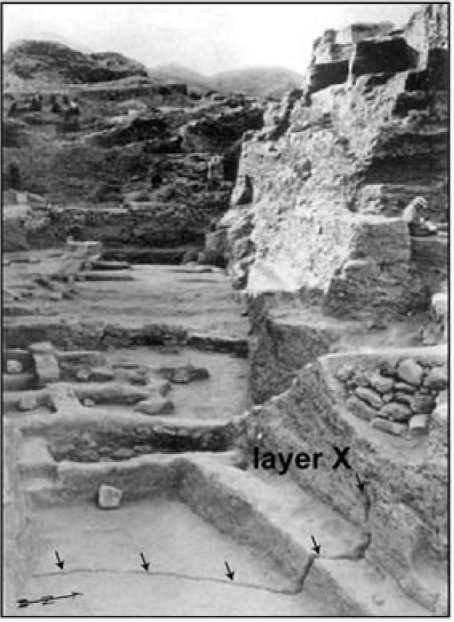

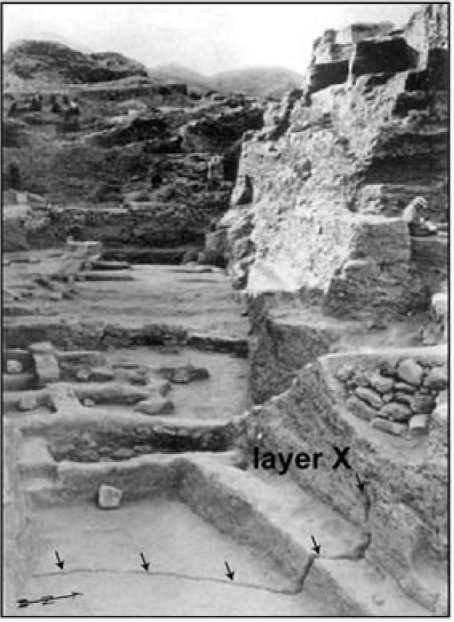

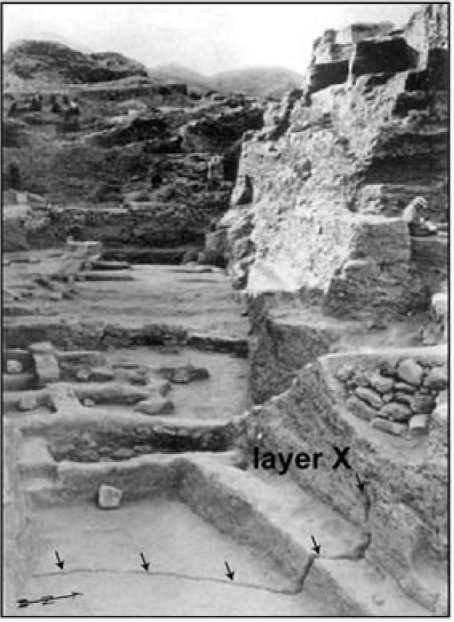

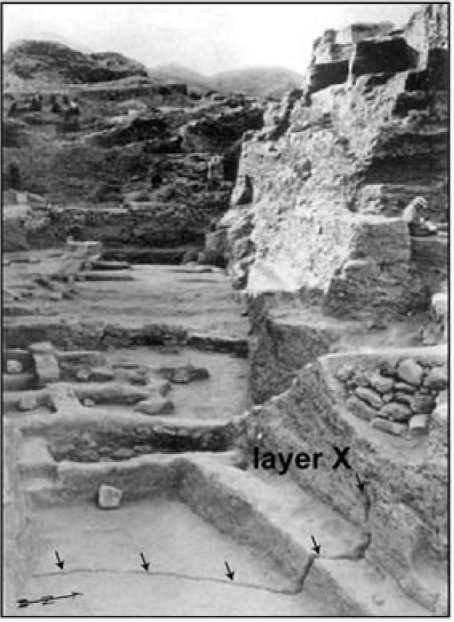

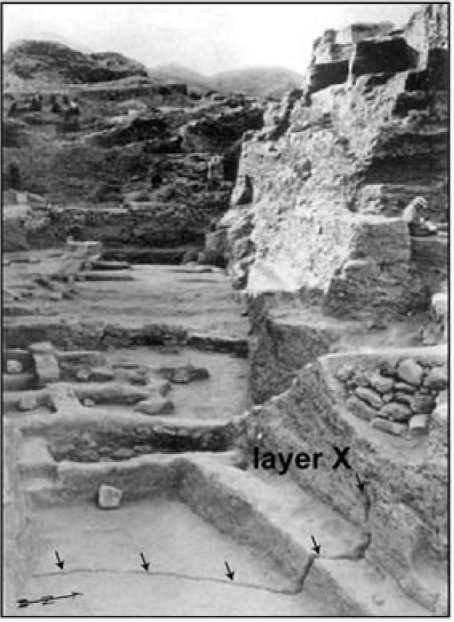

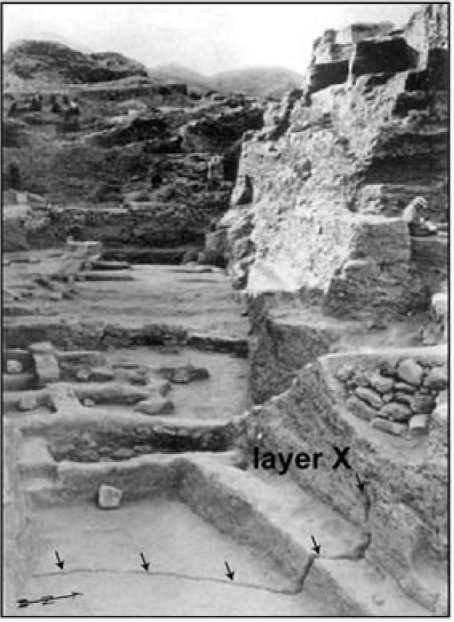

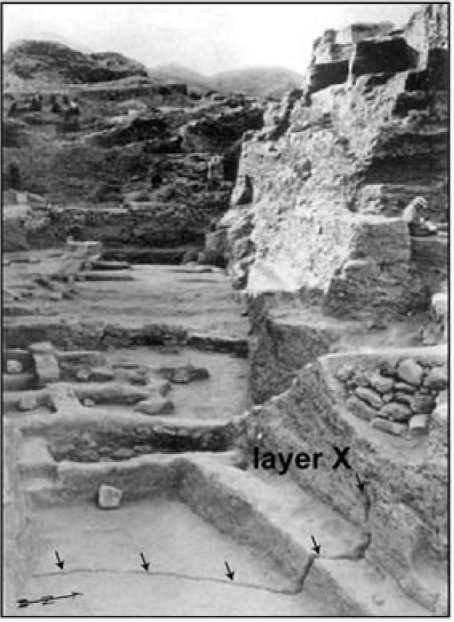

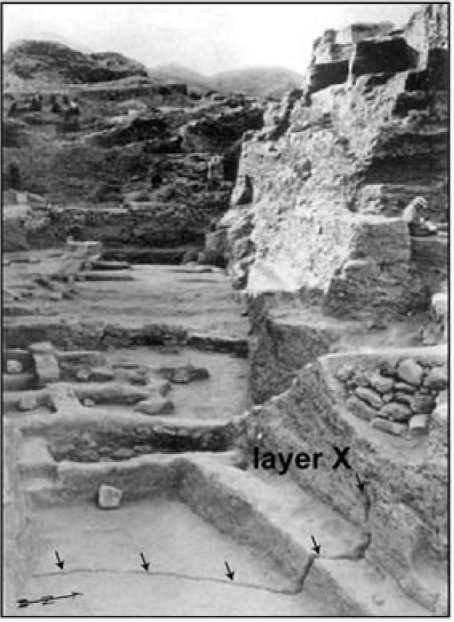

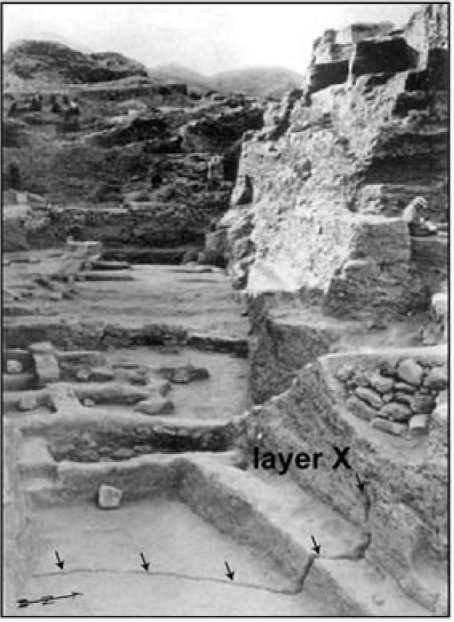

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3d Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3d

Figure 3d

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(d) East view of the Garstang excavation. Visible in the foreground is a fracture crossing the floor and the adjacent wall affecting layer X, dated as the latest stage of Pre–Pottery Neolithic B. Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3e Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3e

Figure 3e

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(e) The Garstang excavation as appears today (same shot position). Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3f Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3f

Figure 3f

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(f) Black arrows point to a fracture crossing a pavement and a skeleton. An apparent displacement of skull versus body is observable. The white circle inscribes the possible correspondence between the cervical and neck bones (black dots). Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 General View of

Area A and sampling of destruction layer F.1688 west of Tower A1 from Nigro and Taha (2013)

- Fig. 3 Mudbricks visible

on the northern face of Tower A1 Wall W.15 with possible destruction layer above from Nigro and Taha (2013)

- Fig. 7 Earthquake crack

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 8 Earthquake crack

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 18 Collapsed mudbricks

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 20 EB IIIB final

destruction in Palace G from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 21 tumbled down

EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 22 Section of the

tumbled down EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 23 EB IIIB final

destruction in Building B1 from Nigro (2014)

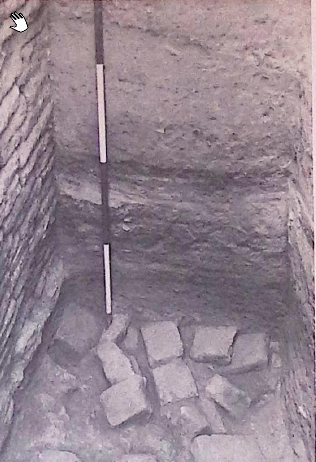

- Plate 200a Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 200b Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Fig. 16 Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Nigro (2014)

- Plate 201a 3rd wall cutting

into top of 2nd wall at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 201b 3rd wall cutting

into wall below at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

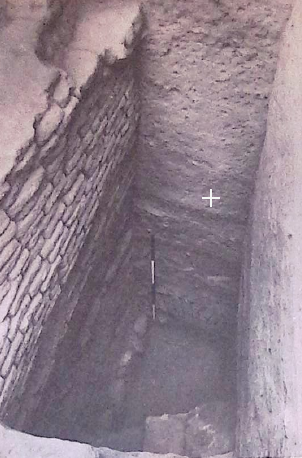

- Plate 79b Tower built

against Town Wall A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 80a Foundations of

tower and face of Town Wall B from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 100a Stone foundation

of phase Tr.II.xlviii house OBM from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Fig. 38 Collapsed town wall

of the Early Bronze Age from Kenyon (1978)

- Fig. 38 Annotated version of

the collapsed town wall of the Early Bronze Age from Kenyon (1978) and modified by JW

- Fig. 18 Collapsed bricks

and burnt beams in EB IIIA Inner Gate from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 3 Outer wall of Jericho

from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 4 Final Bronze Age

destruction layer from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 5 Burned storage jars

full of grain uncovered in the fire destruction layer of Jericho 1Vc from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 9 The "Middle Building"

at Jericho from Kennedy (2023)

- Pl. 62A Middle Bronze Buildings

overlain by wash of burnt material from Kenyon (1957)

- Pl. 62A Middle Bronze Buildings

overlain by wash of burnt material (annotated) from Kenyon (1957)

- Fig. 1 Oblique Aerial View

of Tell es-Sultan from Nigro (2016)

- Fig. 3a Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(a) Black arrows point to fractures crossing the floor and the perimeter wall of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B houses. Original picture from Kenyon (1981).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3b Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 3c Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3c

Figure 3c

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(c) View from the top of a complete northward collapse of a wall, giving the illusion of a pavement. Original picture from Kenyon (1981).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3d Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3d

Figure 3d

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(d) East view of the Garstang excavation. Visible in the foreground is a fracture crossing the floor and the adjacent wall affecting layer X, dated as the latest stage of Pre–Pottery Neolithic B. Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3e Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3e

Figure 3e

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(e) The Garstang excavation as appears today (same shot position). Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 3f Coseismic Effects

Photo from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 3f

Figure 3f

Photos illustrating some of the effects caused by seismic shaking at Tell es-Sultan (numbered as in Figure 2 and Table 2).

(f) Black arrows point to a fracture crossing a pavement and a skeleton. An apparent displacement of skull versus body is observable. The white circle inscribes the possible correspondence between the cervical and neck bones (black dots). Original picture from Garstang and Garstang (1948).

click on image to open in a new tab

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 General View of

Area A and sampling of destruction layer F.1688 west of Tower A1 from Nigro and Taha (2013)

- Fig. 3 Mudbricks visible

on the northern face of Tower A1 Wall W.15 with possible destruction layer above from Nigro and Taha (2013)

- Fig. 7 Earthquake crack

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 8 Earthquake crack

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 18 Collapsed mudbricks

from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 20 EB IIIB final

destruction in Palace G from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 21 tumbled down

EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 22 Section of the

tumbled down EB III city-wall from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 23 EB IIIB final

destruction in Building B1 from Nigro (2014)

- Plate 200a Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 200b Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Fig. 16 Collapsed bricks

at Site A from Nigro (2014)

- Plate 201a 3rd wall cutting

into top of 2nd wall at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 201b 3rd wall cutting

into wall below at Site A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 79b Tower built

against Town Wall A from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 80a Foundations of

tower and face of Town Wall B from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Plate 100a Stone foundation

of phase Tr.II.xlviii house OBM from Kenyon et al. (1981)

- Fig. 38 Collapsed town wall

of the Early Bronze Age from Kenyon (1978)

- Fig. 38 Annotated version of

the collapsed town wall of the Early Bronze Age from Kenyon (1978) and modified by JW

- Fig. 18 Collapsed bricks

and burnt beams in EB IIIA Inner Gate from Nigro (2014)

- Fig. 3 Outer wall of Jericho

from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 4 Final Bronze Age

destruction layer from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 5 Burned storage jars

full of grain uncovered in the fire destruction layer of Jericho 1Vc from Kennedy (2023)

- Fig. 9 The "Middle Building"

at Jericho from Kennedy (2023)

- Pl. 62A Middle Bronze Buildings

overlain by wash of burnt material from Kenyon (1957)

- Pl. 62A Middle Bronze Buildings

overlain by wash of burnt material (annotated) from Kenyon (1957)

- from Nigro (2016)

Table 1

Table 1Correlation between Archaeological Periodization and the Stratigraphic Phases of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition at Tell es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho

Click on image to open in a new tab

Nigro (2016)

- from Nigro (2006)

Table 1

Table 1Correlation between Kenyon’s periodization and the stratigraphic phases of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Nigro (2006)

- from Bienkowski (1986)

| Period | Date | Greece | Egypt | Kenyon's Pottery Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBI | c.1550–1400 | LHI, LHIIA and LHIIB | Start of 18th Dynasty – early Amenophis III | A, B and C |

| LBIIa | c.1400–1300 |

LHIIIA1 LHIIIA2 |

Amenophis III – Amarna Amarna – start Seti I |

D |

| LBIIb | c.1300–1200 | LHIIIB | Seti I – Ramesses III yr 1 | E and F |

- from Chat GPT GPT-5.1 Thinking, 23 November 2025

- from Kathleen Kenyon in Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description (verbatim from Kenyon) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epipaleolithic | Natufian culture | 9687 BCE ± 107 to 7770 BCE ± 210 | "The earliest remains, found in an area near the north end of the mound, belong to the Natufian culture. Carbon-14 dates for the deposit range from 9687 BCE ± 107 to 7770 BCE ± 210. The nature of the remains is not clear, but an oblong structure enclosing a clay platform, with a group of sockets for uprights set in a wall, too close together to be structural, may represent a sanctuary. It is possible that this was a sanctuary set up by hunters near the spring of Jericho." |

| Proto-Neolithic | Transitional to PPNA | late 10th–9th millennium BCE (implied) | "At this spot, the very lowest deposit consisted of a layer 4 m thick, composed of a close succession of surfaces bounded by slight humps. The humps clearly represent the bases of flimsy walls, perhaps little more than the weighting down of tents of skins, although rudimentary mud bricks were present in the form of balls of clay. ... The surfaces that made up this 4 m of deposit represent the remains of a succession of slight structures, huts, or tents seemingly suitable to the needs of a nomadic or seminomadic group. But the creation of this great depth of deposit indicates that these people were no longer nomadic, or at least that they returned to Jericho at regular and frequent intervals, perhaps practicing some form of transhumance. It is a truly transitional stage of culture, and the flint and bone industries are clearly derived from the Epipaleolithic Natufian." |

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic A |

PPNA walled town | late 9th–8th millennium BCE (C-14 ca. 8340–6935 BCE) |

"Above this deposit, the solid structures appear already fully developed, but their circular plan, usually single roomed, is clearly derived from that of a primitive hut. These circular structures are built with solid walls of piano-convex mud bricks, often with a hog-backed outline. ... The construction of these solid houses marked the establishment of a fully sedentary occupation, and the expansion of the community was rapid. Over all the area occupied by the subsequent Bronze Age town, and projecting appreciably beyond it to the north and south, houses of this type have been identified. The total area covered was almost 10 a. ... The expansion of the settlement was soon followed by a step of major importance, the construction of a town wall. ... On the west side, the first town wall was associated with a great stone tower (8.5 m in diameter and preserved to a height of 7.75 m) built against the inner side of the wall. ... Tower and wall together furnish evidence of a degree of communal organization and a flourishing town life wholly unexpected at a date that, as will be seen, must be in the ninth millennium BCE. ... The carbon-14 datings obtained for different stages in the deposits of this period range from 8340 BCE ± 200 to 6935 BCE ± 155." |

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic B |

PPNB town | 7379 BCE ± 102 to 5845 BCE ± 160 | "The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B culture arrived at Jericho almost fully developed and differed from its predecessor in almost every respect. The most immediately obvious contrast was the architecture. The houses were far more elaborate and sophisticated. The rooms were comparatively large, rectangular in plan, and grouped around courtyards. ... Floors and walls were covered with a continuous coat of highly burnished, hard lime mortar. ... Bowls and dishes of white limestone, some of them very well made, became very common. ... The most remarkable evidence bearing on religious practices was the discovery of ten human skulls with features restored in plaster, sometimes with a high degree of skill and artistic power. ... These plastered skulls were most likely associated with a cult of ancestor worship. ... The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B settlement seems originally to have been undefended, for the earliest town wall found was later than a long series of house levels. ... The carbon-14 datings range from 7379 BCE ± 102 to 5845 BCE ± 160." |

| Pottery Neolithic A |

Early Pottery Neolithic | after PPNB, before PN B |

"The evidence for the next period of occupation appears in the form of pits cut into this eroded surface. These pits, which often were as deep as 2 m and about 3 m across, and in one instance as deep as 4 m, ... are therefore clear that these were occupation pits, or the emplacements of semisubterranean huts. ... The first pottery appears in these pits at Jericho. Analysis of it suggests that two different and successive groups are represented, called Pottery Neolithic A and Pottery Neolithic B. The A pottery, consisting of vessels decorated with burnished chevron patterns in red, and also of extremely coarse, straw-tempered vessels, corresponds with that ascribed to stratum IX by Garstang." |

| Pottery Neolithic B |

Later Pottery Neolithic | after PN A, before EB |

"The B pottery, consisting of jars with bow rims, jars and bowls with herringbone decoration, and vessels with a mat red slip, corresponds with that ascribed to stratum VIII. ... With the appearance of pottery there was a change in the flint industry, most noticeably the use of coarse, instead of fine, denticulation for the sickle blades. By far, the greatest amount of finds from the period came from the pits. Above the pits, however, there were some scanty remains of buildings. Too little was found to establish any house plans, but their characteristic feature was the round and the plano-convex bricks, not found at any other period." |

| Gap / erosion | Post-Neolithic pre-EB |

Ghassulian period (probable) |

"Between the Pottery Neolithic and the next stage at Jericho there is another gap, perhaps covering the period of the Ghassulian culture. The gap is indicated by the usual erosion stage and by a complete break in the artifacts, particularly the pottery." |

| Proto-Urban EB | Proto-Urban (Early Bronze) |

toward the end of the fourth millennium |

"Toward the end of the fourth millennium, a completely new people arrived in the country. It is probable that some of the earliest evidence of their arrival is to be found at Jericho. ... The newcomers, for the first time, buried in rock-cut tombs, a practice that was to become standard at least until the Roman period. They brought with them pottery in simple forms—bag-shaped juglets and round-based bowls. ... The Jericho evidence suggested that the newcomers could be divided into A, B, and C groups. ... It is for this reason that the classification Proto-Urban is suggested." |

| Early Bronze Age | Urban EB town | 3rd millennium BCE | "From the amalgamation of influences emerged a culture responsible for the walled towns that at Jericho, as elsewhere, are the country's characteristic feature for the greater part of the third millennium BCE. Jericho at this stage had grown into a steep-sided mound beside the spring responsible for its continued existence. Around its summit can be traced the line of mud-brick walls by which the Early Bronze Age town was defended. ... The section that was cut completely through the walls on the west provided evidence of seventeen stages. ... The remains, however, showed a succession of solidly built and spacious structures that confirms the impression that this was a period of full urban development. ... The end of Early Bronze Age Jericho was sudden. A final stage of the town wall, which in at least one place shows signs of having been hurriedly rebuilt, was destroyed by fire." |

| Intermediate EB–MB |

Intermediate EB–MB (MB I) |

Amorite expansion (late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE) |

"Between the layers associated with the two types of houses was an accumulation of a new type of pottery associated with newcomers who apparently were not yet building houses but must still have been living in tents. The stage (elsewhere called Middle Bronze Age I) is best called the Intermediate Early Bronze- Middle Bronze period, for it represents an intrusion between the Early Bronze and Middle Bronze ages, differing from both in every important respect. The newcomers were nomads and pastoralists. Even when they started to build houses, they did not develop a true urban center. The houses straggle down the slopes of the mound and over the surrounding country, and there is no evidence of a town wall. The tribal and nomadic character of the population is shown by its burial customs. The dead were buried individually in separate tombs, a feature that sharply distinguishes this period from the preceding and succeeding ones." |

| Middle Bronze Age (early) |

Middle Bronze Age (MB II) |

probably end of MB I / late 19th c. BCE onward |

"An abrupt cultural break marks the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (according to Kenyon's terminology, it is more often called the Middle Bronze Age II). The evidence at Jericho is very clear. The break is again in type of settlement, burial customs, tools and weapons, and pottery. ... The exception to this considerable erosion was in the center of the east side of the town, immediately adjacent to the spring. Here, there was a crescent- shaped hollow, presumably because access to the spring prevented the accumulation of the earlier levels. The Middle Bronze Age levels have survived in the hollow. ... The evidence is sufficient to show that from the earliest stages the buildings were substantial. In this respect and in the regularity of their plans, they resemble those of the Early Bronze Age and not those of the Intermediate Early Bronze- Middle Bronze period. ... It is probable, therefore, that the site was first occupied at the end of the Middle Bronze Age I (more commonly referred to as Middle Bronze Age II), perhaps toward the end of the nineteenth century BCE." |

| Middle Bronze Age (glacis) |

MB II fortified town |

later MB II, destroyed c. 1560 BCE |

"For the final stage of the Middle Bronze Age, something more of the town plan can be established. The houses excavated in the 1930-1936 and 1952-1958 expeditions were small dwellings, with small and rather irregular rooms, lining two roads that in parts had shallow cobbled steps going up the slopes. ... This quarter of the town may have been one in which corn millers lived, for in one house that had grain stored on the ground floor, no fewer than twenty-three grinding querns were found in the debris that had fallen from the upper story. ... It is reasonably certain, however, that these building phases belonged to the new type of defenses that appear at Jericho, as at many other sites in the country—the type in which the wall stands on top of a high glacis. The surviving portion at Jericho consists of a revetment wall at the base (without the external ditch found at some sites), an artificial glacis overlying the original slope of the mound and steepening the slope to an angle of 35 degrees, and the face of the glacis surfaced with hard lime plaster. ... Three stages of this glacis can be traced. ... The final Middle Bronze Age buildings at Jericho were violently destroyed by fire. Thereafter, the site was abandoned. ... The date of the burned buildings would seem to be the very end of the Middle Bronze Age, and the destruction may be ascribable to the disturbances that followed the expansion [JW: expulsion?] of the Hyksos from Egypt in about 1560 BCE." |

| Late Bronze Age II | LB II town | reoccupied soon after 1400 BCE; abandoned in 2nd half of 14th c. BCE |

"The site was abandoned during most of the second half of the sixteenth century and probably most of the fifteenth. ... Only very scanty remains survive of the town that overlies the layers of rain-washed debris. These include the building described by Garstang as the middle building, the building he called the palace (although there is no published dating evidence and it could be Iron Age), and fragments of a floor and wall in the area excavated from 1952 to 1958. Everything else disappeared in subsequent denudation. The small amount of pottery recovered suggests a fourteenth-century BCE date. This date is supported by the evidence from five tombs excavated by Garstang that were reused in this period. It is probable that the site was reoccupied soon after 1400 BCE and abandoned in the second half of the fourteenth century." |

| Iron Age II | Iron Age occupation |

mainly 7th c. BCE | "According to the biblical account, Hiel the Bethelite was responsible for the first reoccupation of Jericho in the time of Ahab (early ninth century BCE). No trace of an Iron Age occupation as early as this has so far been observed, but it may have been a small-scale affair. In the seventh century BCE, however, there was an extensive occupation of the ancient site. Evidence of this does not survive on the summit of the mound but is found as a thick deposit, with several successive building levels, on its flanks. On the eastern slope, a massive building from this period was found, with a tripartite plan common in the Iron Age II. The pottery suggests that this stage in the history of the site lasted until the period of the Babylonian Exile." |

| Persian & later | Persian period and later reuse |

Persian to Early Arab |

"A few finds, including jar handles with the seal impression yhwd (Yehud), the name of the satrapy of Judea, belong to the Persian period. Thereafter, the site near `Ein es-Sultan was abandoned. Later periods are represented only by some Roman graves and a hut from the Early Arab period." |

- from Kenyon (1981:3-4)

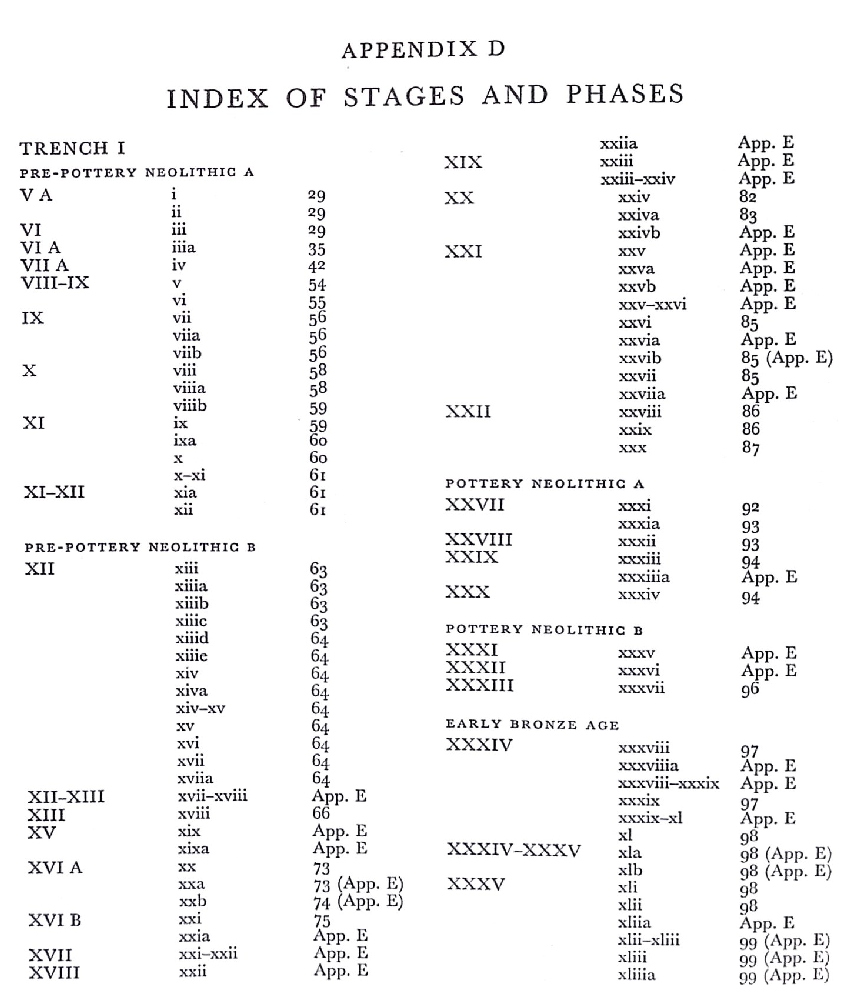

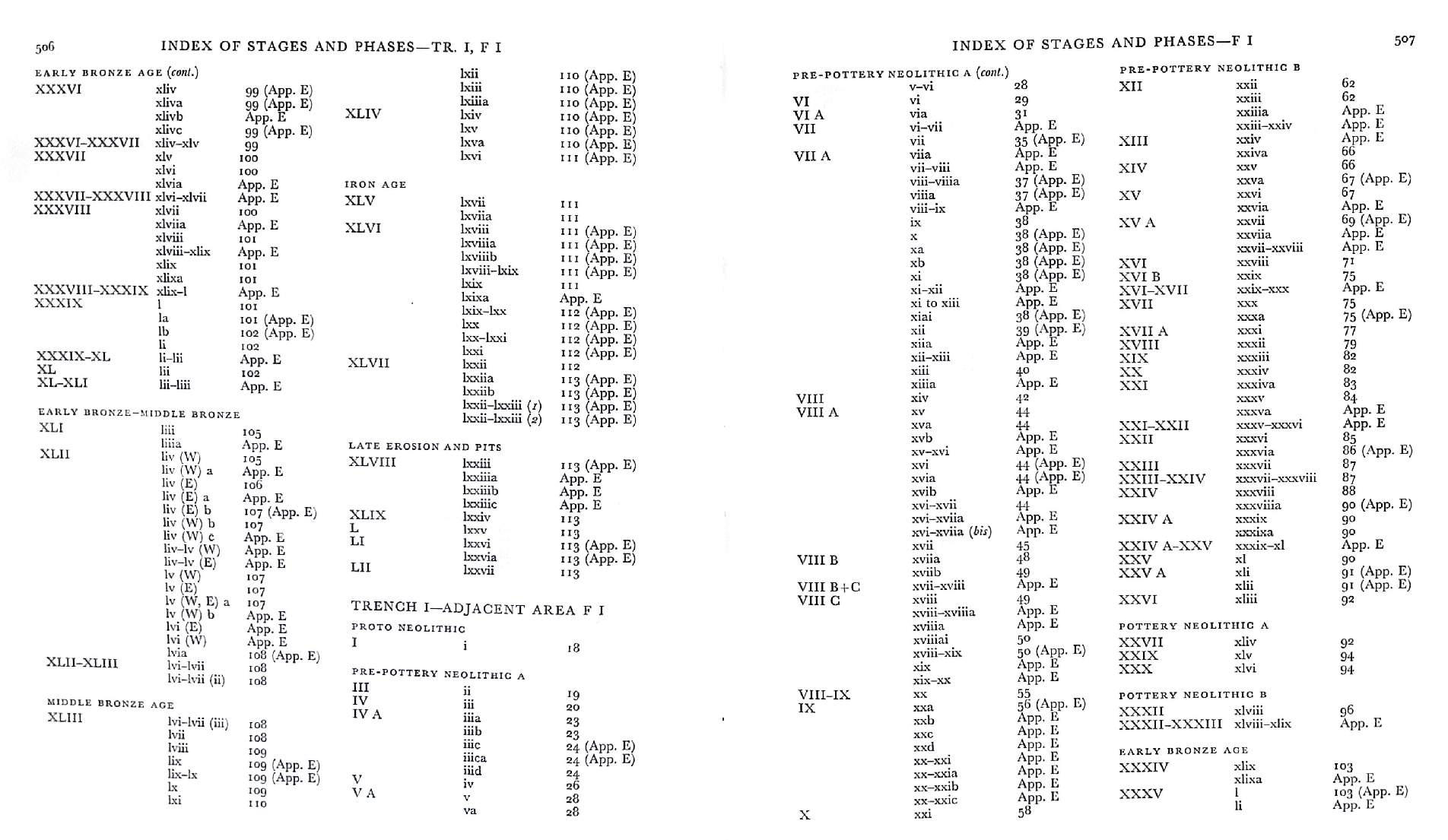

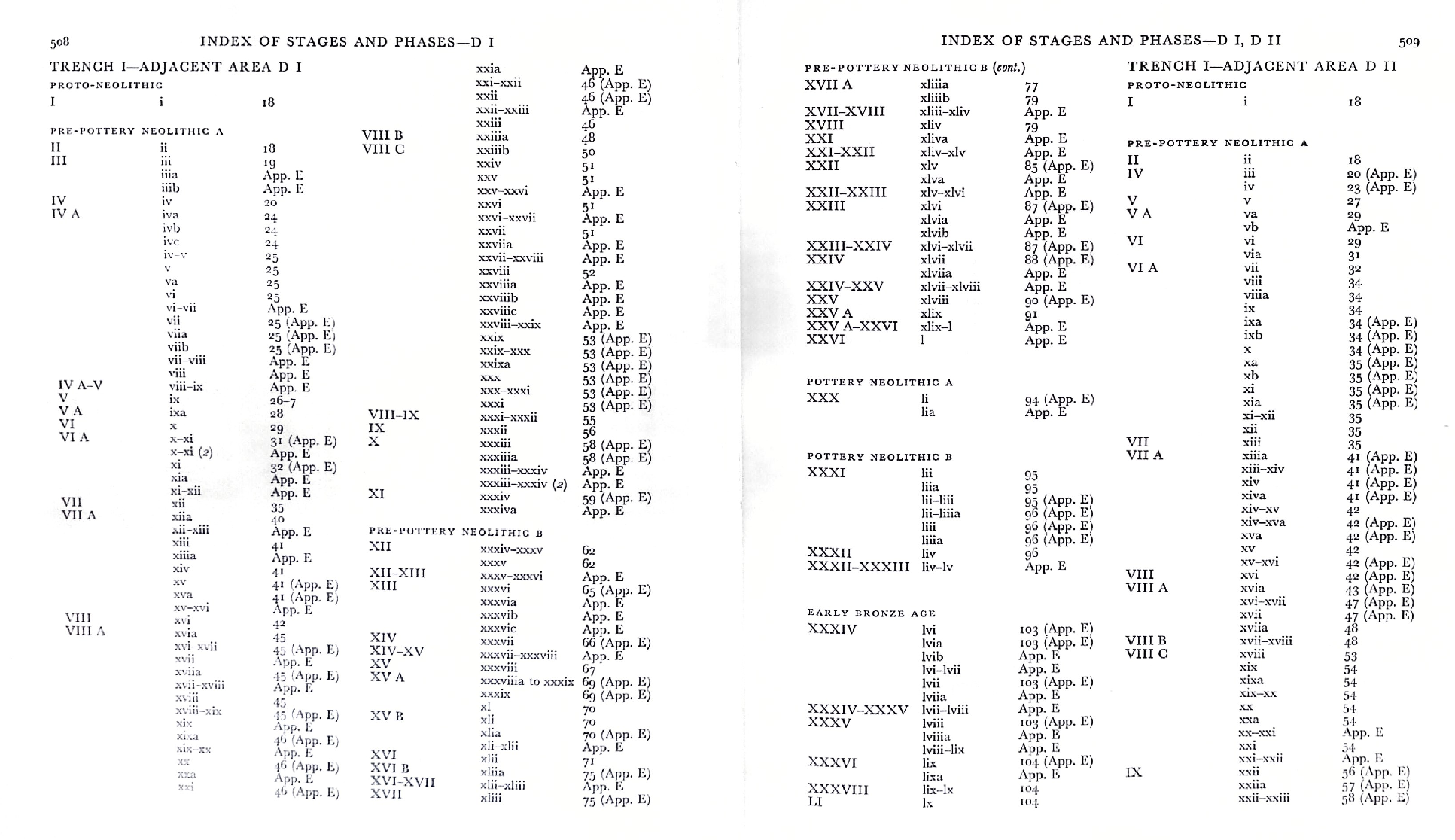

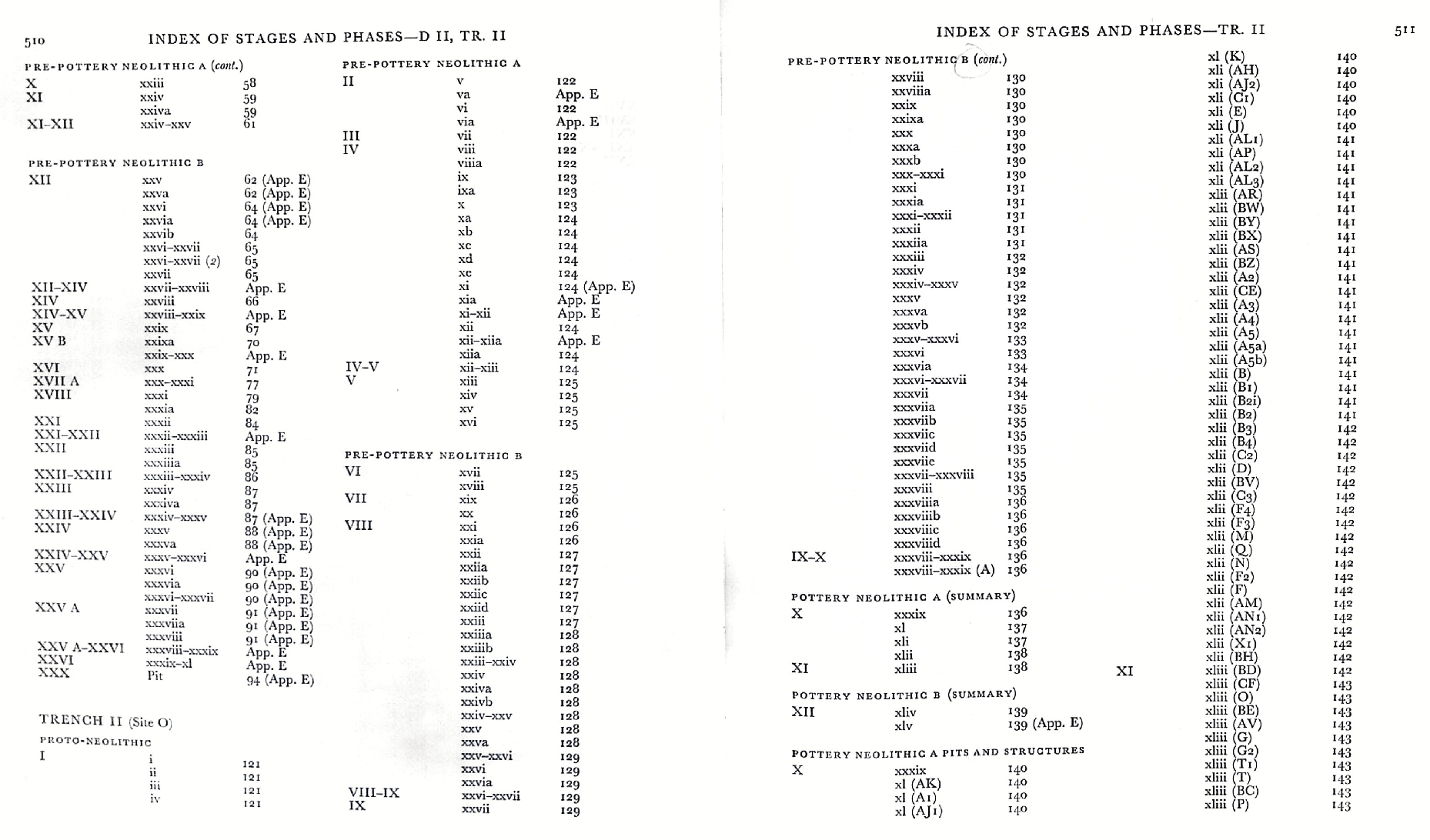

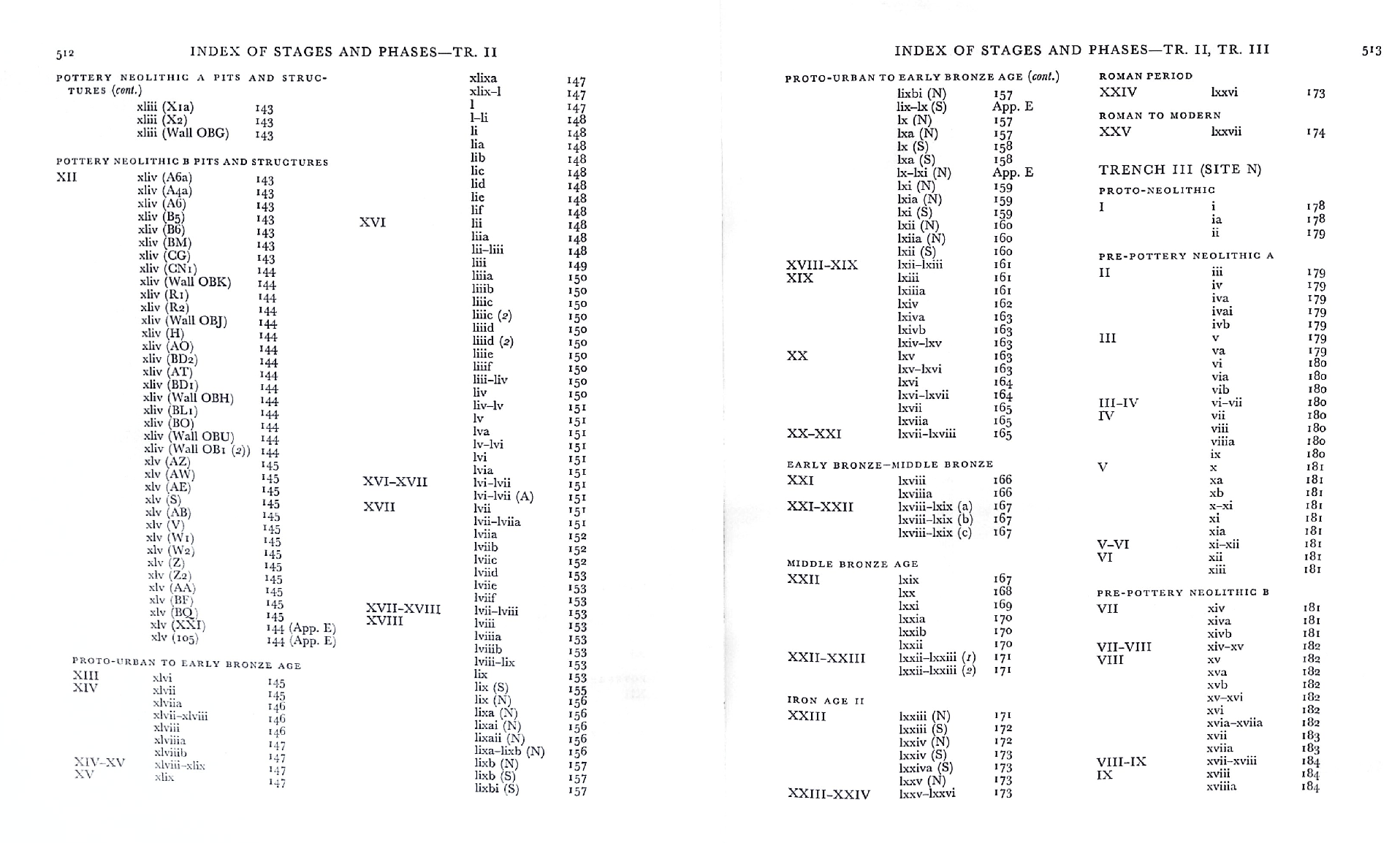

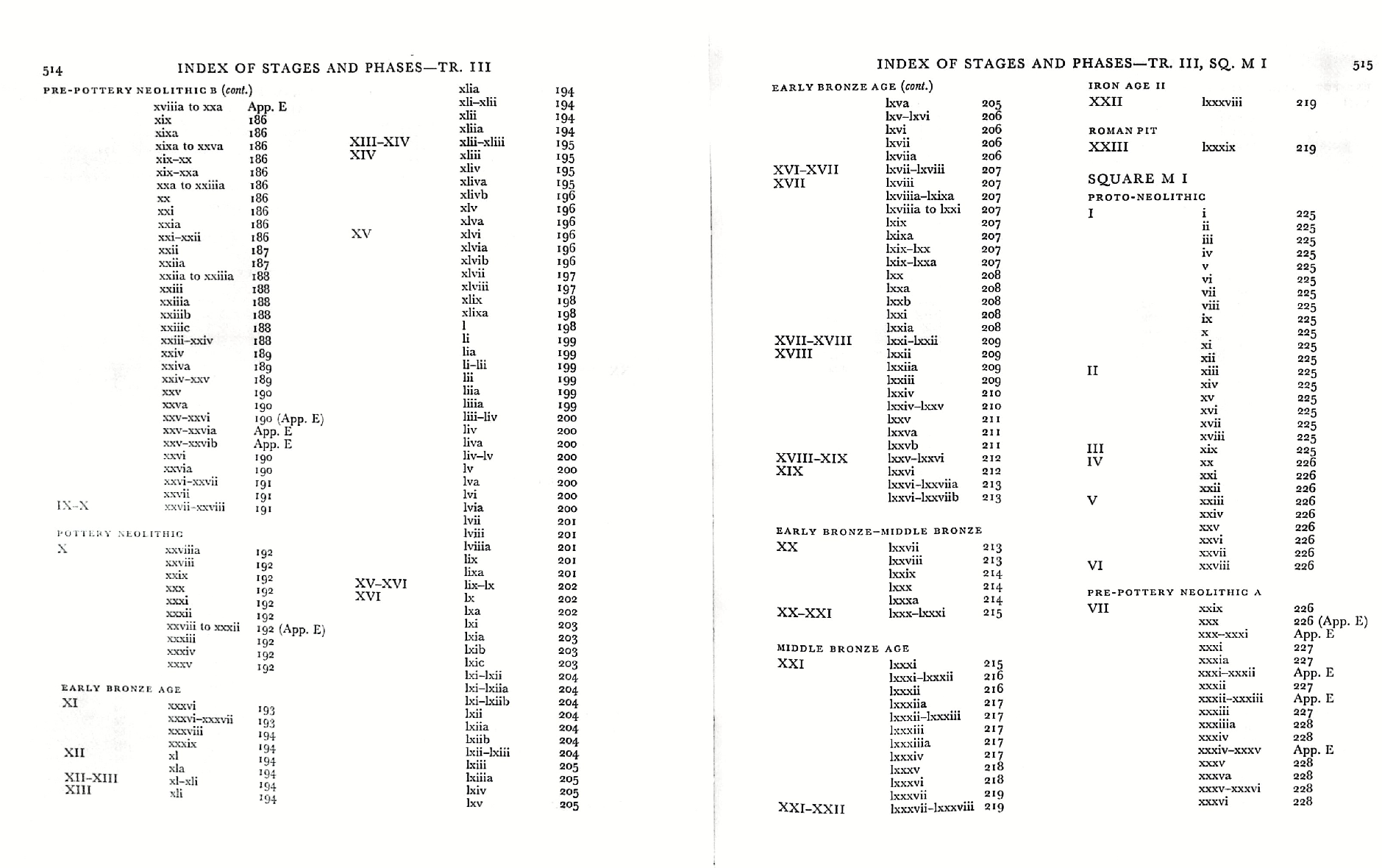

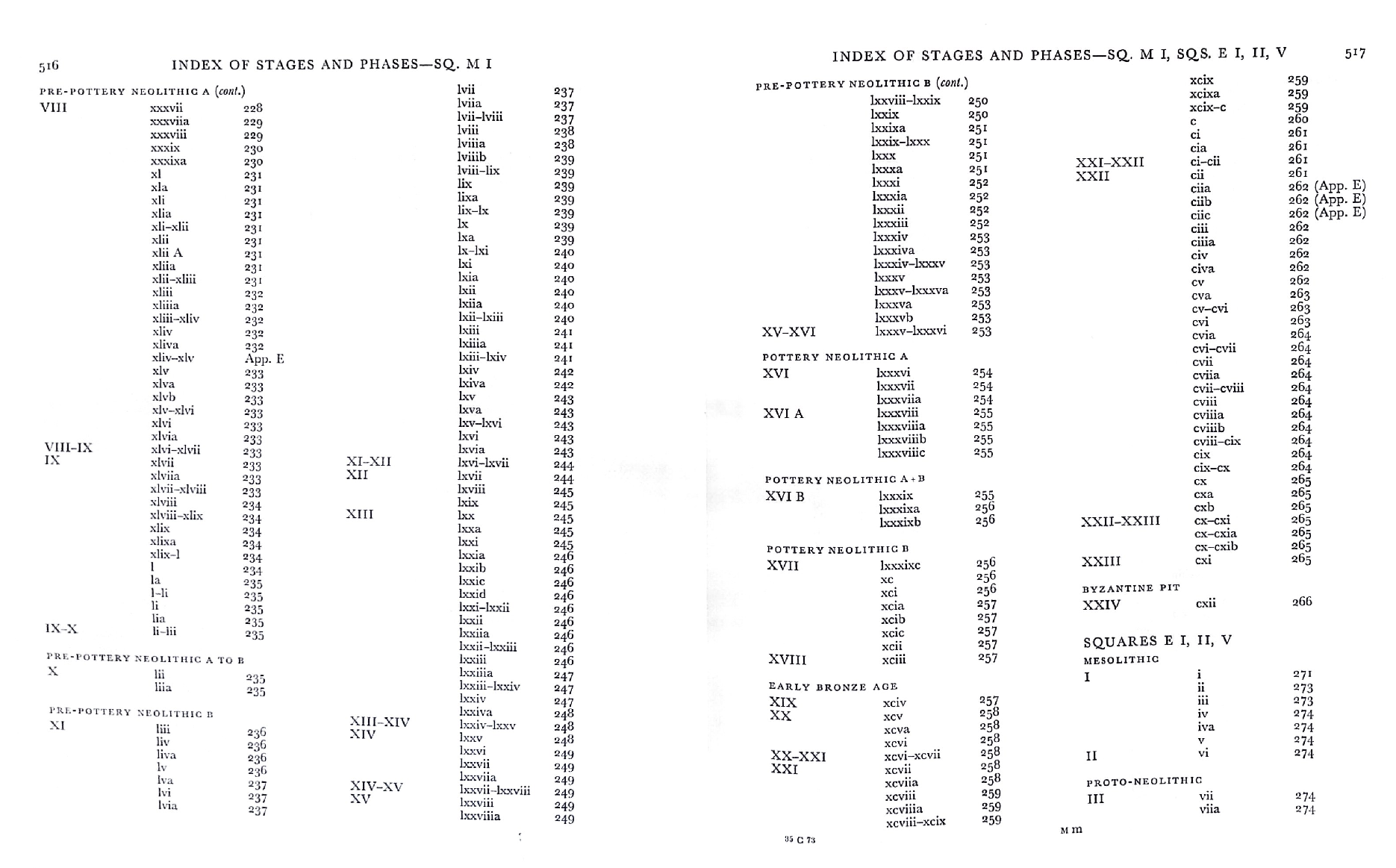

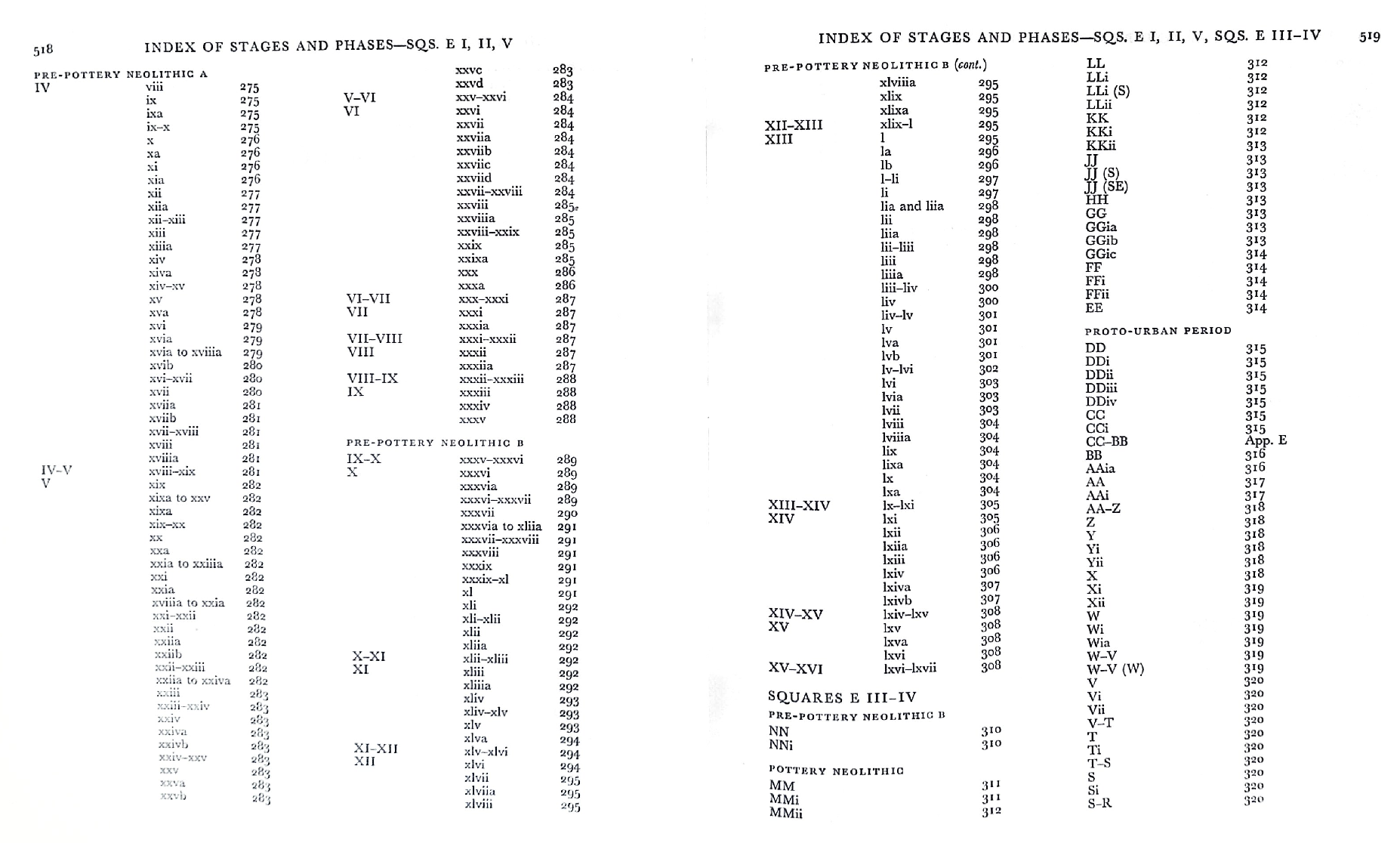

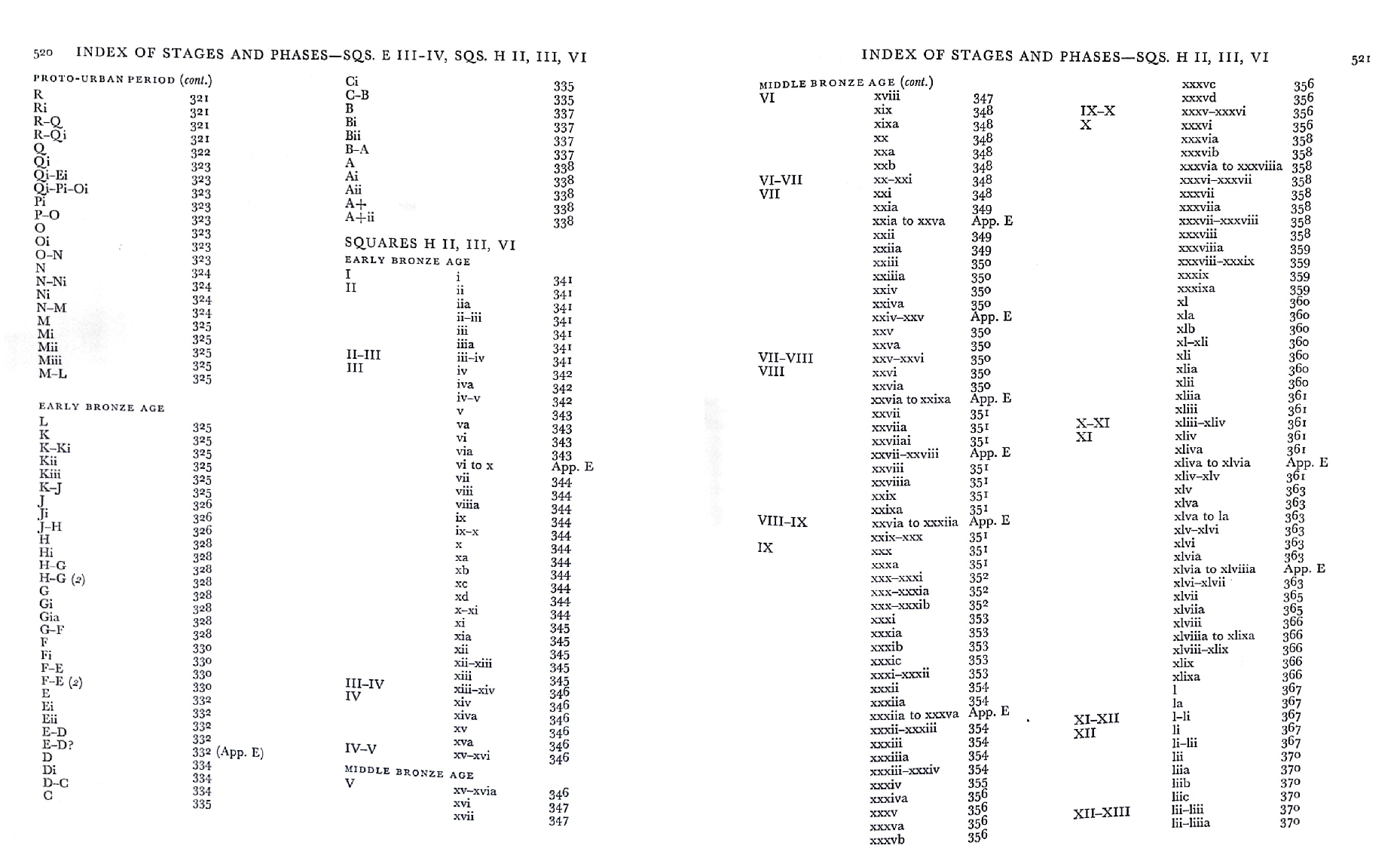

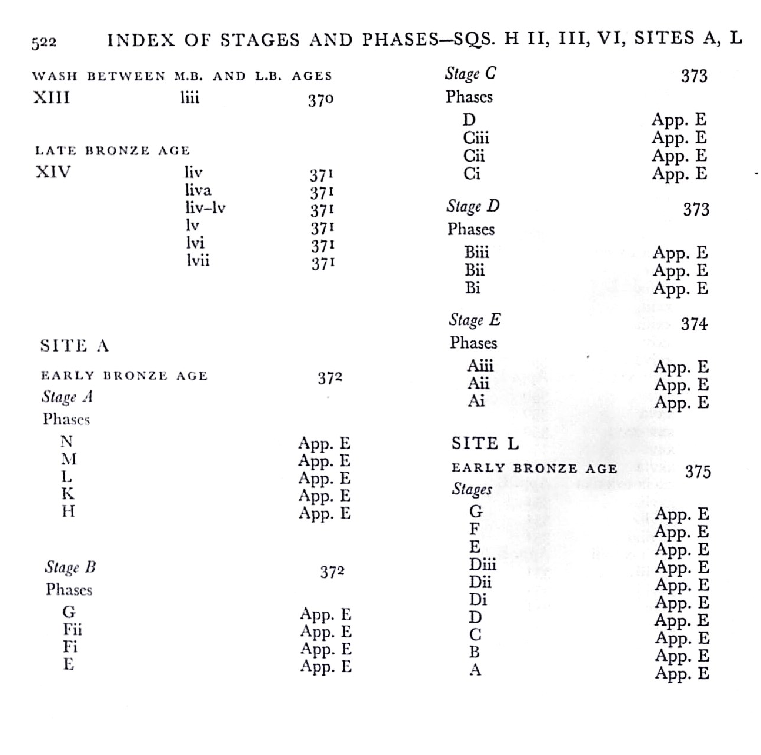

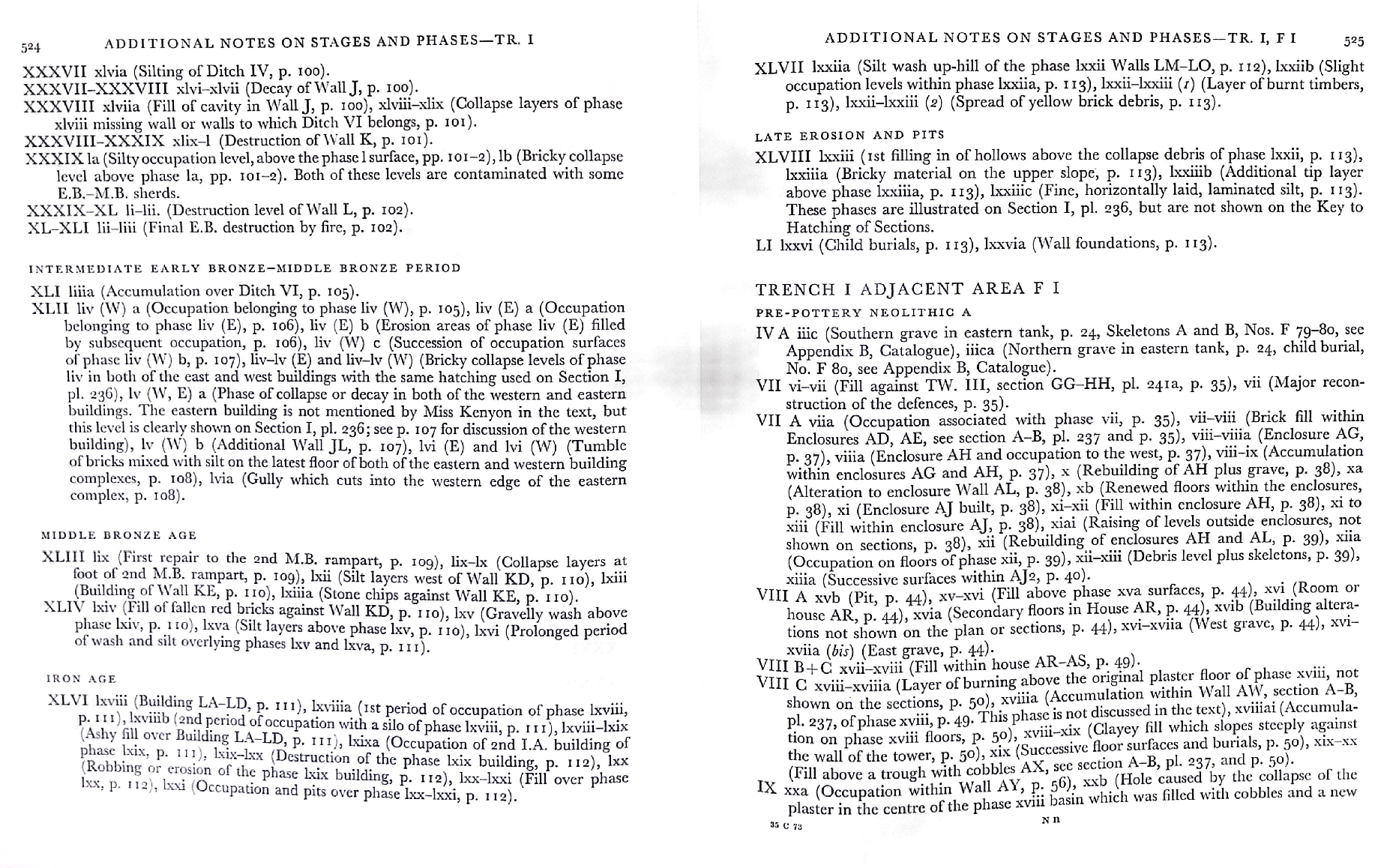

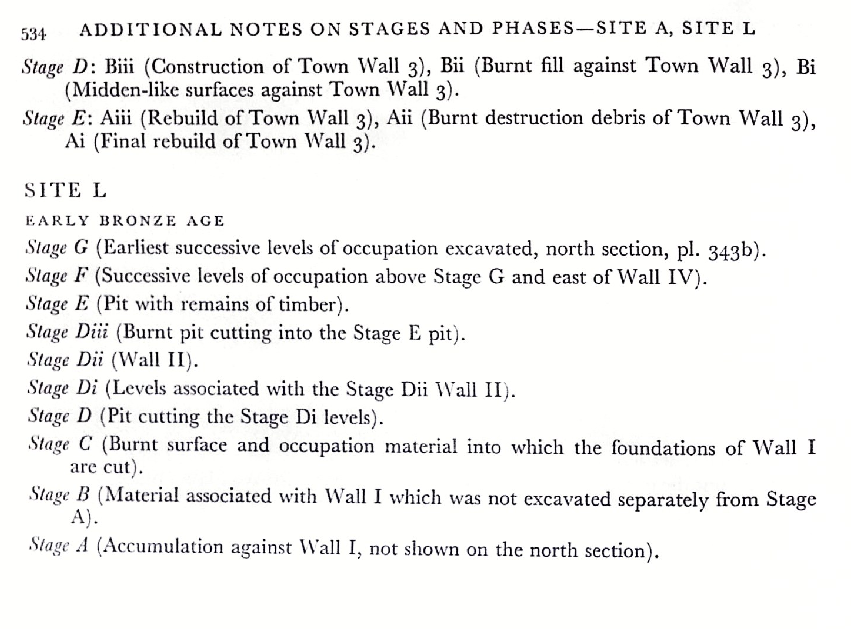

Each site is recorded separately, for only a stratigraphical link could prove the relationship of phases in different sites. In each site the deposits as recorded in the field are linked into phases by relation to structures, starting with i at the bottom. Normally, the construction levels, floor levels, and make-up and contents of walls are numbered, e.g. M I. xiv, though it is of course recognized that such levels probably contain mainly derived material. Occupation deposits would be numbered xiv a, with possibly xiv b as well, etc. Material from these deposits is thus more certainly contemporary with the structures. Very slight alterations in plan or structure may be numbered, e.g. xiv c, but normally an appreciable alteration would be called, e.g., phase xv. Usually between building phases there is a layer of collapse debris, which is numbered, e.g. M I. xiv-xv. It may contain material belonging to the last occupation of the structure, but could include objects dropped by later inhabitants tidying up the site, and could also include much earlier objects incorporated in bricks forming part of the collapse. The number of phases in most sites may seem large, but it must be remembered that when a wall has been reconstructed from a low level, a very considerable collapse of that building is indicated.

These structural phases are in each site grouped into Stages, indicating a main alteration in plan. Usually a new Stage is given when there is a complete break in plan. Some of the Stages cover a large number of phases, in which one building continues throughout though the others may change; an example is in E I, II, V, phases ix to xiv, where building E 3 continues throughout.

These Stages likewise cannot be applied from site to site. What possible connections there are are discussed in Jericho IV. The only exception to this is Trench I, and Squares F I, D I, and D II, where the phases in the different areas can be linked by their relationship to the defenses and in part by direct connections.

The only exception to this method of numbering the phases is Squares L I–IV. The pottery from the upper levels of this site was partly published by Professor J. B. Hennessy, at a time when it was still classified under the working annotations with A at the top, and so on downward in letters. It was felt that it would cause confusion to introduce new designations, and those used by Professor Hennessy, from Q up to A, have been retained. Some further excavations in this area were carried out after the end of the main excavations, and this system has been retained, back to Z, followed by AA, BB, as late as NN.

Incidentally, all sites were in origin sorted under letters, though normally with A at the bottom since the site had been excavated to bedrock. Museums and other collections where the material is deposited have been provided with correlation lists between the notations with which the object is marked and published designations, and also with the field notebook numbers.

The position of the excavation areas is shown on fig. 1. Since the areas were selected without strict reference to the main grid plan, which would in any case have been difficult, measurements are related only to the original excavations. In some cases, a key plan shows the discrepancies that arose in the various areas.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Composite sketch plan of excavations 1907–1958

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon (1981 v.3a)

The complex of walls shown on pl. 254a can only be interpreted on grounds of probable sequence, since the trenches of the earlier excavations have removed almost all stratigraphical evidence. Structurally, the first wall is OCQ, which has a return to the west OOS at the north end, which in W.W. section is obscured by robbing. Against this wall was built wall OCR, in phase lxiv incorporated in a town wall. Against wall OCR were built walls OCP and OCM, and between wall OCQ and wall OCP was built wall OCX. As the plan, pl. 251c, shows there are butt joints at all these junctions, but, in the absence of stratigraphical evidence, they are all taken as contemporary, and the butt joints are interpreted as structural features only.

The lower courses of wall OCP are continuous with a return to the east, wall OCN, as are those of OCQ with a return to the west, ODA. Wall OCN stops 0.85 m. short of wall OCM, leaving a doorway which is maintained through three building periods (pl. 102b). It is for this reason that it is presumed that wall OCO belongs to a later period, since the gap would make no sense if there were a wall immediately to the south, for c. 1.25 m. of the first build of this wall survived above the floor level belonging to the room. There is, however, a complication about wall OCN. As already stated, the lower courses are continuous with wall OCP. The upper courses, however, have a butt joint against the existing wall on this line (see pls. 103b and 104a), which is later than the phase lxi rebuild of wall OCO (see below, p. 159). One interpretation could be that wall OCN was never more than a sill-wall. This is not very probable, since its surviving height is c. 1.00 m. above the contemporary surface. It seems more likely that there had been butt joints between walls OCP and OCQ against the superstructure of wall OCN, perhaps as an anti-earthquake device, and that in a destruction preceding phase lxi wall OCN had collapsed, leaving the butt-ends of wall OCP and OCQ standing. In the absence of stratigraphical evidence, there can be no certainty

The southern ends of walls OCM, OCP, and OCQ were subsequently incorporated in town wall ODR of phase lxiii (see pl. 104b; at the stage this photograph was taken, the trench had not been extended to the east to reveal wall OCM), and wall OCR was incorporated in town walls ODS of phase lxiv. It was therefore at first thought that they were casemates in a defensive system. This hypothesis must be discarded on a number of grounds. None of the walls which eventually made up the wall ODR complex, as shown in the east section, 0 m. N., was in itself thick enough to form a town wall. Even if there were not the difficulty of the doorway through wall OCN, wall OCO would not be strong enough to constitute a town wall on its own, against which a casemate complex might subsequently have been built. Individual walls in casemates can be thin, but are only a substitute for a solid thick town wall if at least the lower part of the space between is filled with earth; this was certainly not the case, for the floor level remained at the level of the foundations of the walls (c. 51.30 m. H.), at least until phase lxii. Finally, wall OCQ runs through well to the north of the subsequent town-wall lines, forming a large room that is certainly not a casemate, and effectively dissociates the complex from a possible defensive plan.

- from Kenyon (1981:325)

The new building was on entirely different lines. But this was so completely destroyed in the subsequent erosion and in phase L that the remains are entirely disjointed and nothing can be made of the plan. The walls are still on varying alignments, and not on the plan orientated approximately on the points of the compass, which was established in phase J. The curved wall ZY in the north-west corner may perhaps be part of an apsidal building. Thus though the stratigraphic and structural break was complete, there probably was not a break in architectural tradition.

Within the phase, there was some rebuilding, with wall ZZ being refaced. A considerable bricky collapse marks the end of this period, and precedes the midden fill of phase L.

- from Kenyon (1981:328)

The western building was destroyed by fire at the end of phase H; the fire may have extended to the buildings to the east, but the evidence there was less clear. The whole of the sloping courtyard was covered by burnt wood and debris, particularly thick round the line of posts and by the doorway in ZAV–ZAW. Pl. 176b shows some of the burnt beams, and also the steeply sloping floor.

In position on the floor at the time of the fire were a number of vessels near the line of posts, a stone vessel of unusual form with upright strap handles (fig. 15:3), split in half by the heat of the fire, a small pot (fig. 11:10), both shown in pls. 177a and 177b, and a large jar, crushed into fragments. Beside the easternmost post at this time of final use was a hearth, perhaps the cause of the fire.

In erosion following this destruction, there was a collapse of at least the southern end of the terrace wall ZAO; the combination of a collapsed terrace and a fire may suggest that the cause was an earthquake. The east end of wall ZBA is truncated at 12.12 m. E., and the line of erosion cuts down through the phase K destruction level on which ZBA was built and through that level where it cuts down against the truncated end of wall ZAD. To the erosion period may belong a pit seen in section A–B (pl. 322) between 7.70 m. and 10.50 m. E., base at 4.45 m. H., cutting into wall ZBA, and a smaller one between 7.05–7.95 m. E., both of which cut into the bricky debris on the phase H floor. They are hatched H–G (2).

... Burial group 6B seems to tell a story similar to that deduced from Burials 3 and 4. Skull robbery was the apparent motive for rummaging the group to its very bottom layer. This remained relatively undisturbed once the object of the search had been achieved, while the bones higher up in the mass had clearly been first taken up bodily and then replaced in confusion. Some lingering respect for, or fear of, the dead had, perhaps, prompted the fairly orderly replacement of the group of disjointed long bones near the summit of the collection.

It would appear, then, that the bodies were first interred entire, if unceremoniously, one on top of the other. This possibly bespeaks a hasty evacuation of the city following a deadly plague—for not one of the bones bore signs of violence such as might have been expected as the result of a massacre.Shallow common graves were dug1, the bodies heaped in without regard to age or sex, but with a certain care as to their attitudes. Where any natural arrangement at all could be observed, the bodies seem to have been laid, flexed or contracted, on their sides, not thrown in with limbs outspread as might have been the case with enemy casualties treated as unrespected carrion .

Later—after no long interval—came the skull-quarriers, intent only on their thorough search, for not one cranium in the whole mass escaped them. Legs and arms, whole trunks they dismembered, wrenching the mandibles from the skulls as they were found and throwing them down among the rest of the unwanted, rotting remains. Whether these ghouls were strangers, or the surviving kin of the deceased intent on ritual preservation of the most characteristic parts of their late relations, cannot now be told for certain, but the existence of the plastered skulls points to some such motive. Doubtless there are other caches of the numerous missing skulls somewhere about the tell.

1 In fact there was no clear evidence of graves in most cases, see above p. 78, and also for the suggestion that an earthquake was responsible. [K. M. K.]

- Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone A at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone A between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone B at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone B between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Entire Tell at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan (Entire Tell) between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Legend for Map

of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Legend for Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone A at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone A between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Zone B at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan Zone B between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Map of coseismic

effects in Entire Tell at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan (Entire Tell) between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012) - Fig. 2 Legend for Map

of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Legend for Map of coseismic effects at Tell es-Sultan between 7,500 and 6,000 B.C. (Pre–Pottery Neolithic B). The locations of the effects are marked by numbers (descriptions as in Table 2). Original plan of the Tell modified from Kenyon (1981)

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 4 Archaeoseismic

stratigraphic sections from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Archaeoseismic stratigraphic sections modified from Garstang and Garstang (1948) and Kenyon (1981). Dashed squares in Garstang’s section are the approximate projections of Kenyon’s excavations both from zone A (logs in the inset) and zone B. The time— space relations between the layers and the observed coseismic effects (point numbers as in Figure 2 and Table 2) are illustrated. Horizons of the seismic shaking events recognized within the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period are marked by stars.

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

- Fig. 4 Archaeoseismic

stratigraphic sections from Alfonsi et al. (2012)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Archaeoseismic stratigraphic sections modified from Garstang and Garstang (1948) and Kenyon (1981). Dashed squares in Garstang’s section are the approximate projections of Kenyon’s excavations both from zone A (logs in the inset) and zone B. The time— space relations between the layers and the observed coseismic effects (point numbers as in Figure 2 and Table 2) are illustrated. Horizons of the seismic shaking events recognized within the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period are marked by stars.

Alfonsi et al. (2012)

The ancient town of Jericho is located within the DST fault zone (Fig. 1). The DST is approximately a 1,000-km-long, north–south-striking, left lateral fault system of the active boundary between the Arabian and African plates (e.g., Garfunkel et al., 1981). The DST shows relatively low level of activity in modern time, but larger-magnitude seismic events were documented in the historical reports (Guidoboni et al., 1994; Ambraseys, 2009). One of the main fault strands of the transform zone system is the Jericho fault bounding the Dead Sea basin on the west side (Reches and Hoexter, 1981; Gardosh et al., 1990). A linear escarpment at approximately 6 km south east of modern Jericho is thought to be the surface expression of the Jericho fault on land (Begin, 1974; Lazar et al., 2010). The 1927 earthquake with an M 6.2 (Ben-Menahem et al., 1976; Shapira et al., 1993) is the most recent event that caused widespread damage and casualties in the modern Jericho settlement. The revised 1927 epicenter is approximately 30 km south of the Jericho site (Avni et al., 2002; Fig. 1). Direct evidence of this event at the historical site of Jericho has not been reported by the post earthquake expeditions in the archaeological stratigraphy. Instead, archaeological traces suggest earth quake devastation back in time (Table 1).

The separation of earthquake-related damages in the archaeological layers of Jericho was made possible by the intrinsic characters of the site resulting in the classical Tell structure, where subsequent archaeological levels firmly seal the preceding occupation soils. When the village experienced destruction, there was no possibility, or need, to remove the debris completely, and the inhabitants continued to build on top of the ruins. The superposed archaeological layers in the last 11,000 yr constitute the artificial hill of the ancient Jericho up to about 10 m above the surrounding ground level (Fig. 2). This setting prevents buried and older archaeological levels from severe damaging associated to the younger shaking events.

Town wall encircling the inhabited quarters and the monumental public structures, such as the Neolithic tower (Fig. 2), appeared since the PPNA (8,500–7,500 B.C.), testifying to the presence of an organized social community. The favorable geographical position of the Oasis of Jericho and the environmental conditions are the cause of the continuous occupation of the area. Indeed, the presence of perennial water springs and the climate favored the persistent occupation of Tell es-Sultan from the Natufian (ca. 11,000 B.C.) up to the Iron Age (ca. 1,200 B.C.), with a flourishing occupation during the Neolithic stages. The artifacts of the Neolithic masonry and buildings are made on massive mudstone boulders and on sun-dried brick constructions. These constructions are vulnerable, and local collapses may occur even without earthquakes. Hence, it is critical that the archaeoseismic analysis of the deformation identifies a specific cause to the observed damage, that is, earthquake, fire, flash flood, or deliberate destruction (Marco, 2008).

Figure 2 and Table 2 present a set of features recognized as seismically induced effects at Tell es-Sultan in the archaeological PPNB period (7,500–6,000 B.C.). Both the map and the table were based on our review of the archaeological documents, including the analysis of the stratigraphy, that enhance seismic shaking activities undefined in number and timing. We excluded in the map damage caused by human invasions, structural collapses, fires, or natural hazards other than earthquake. Although the distribution in the map does not reflect the complete damaged field of the Tell, it gives significant information on the nature and extension of the damage itself. Furthermore, when this picture is framed in a chronological context, it allows inferring the time–space occurrence of the individual elements (see the section Time Constraints on the PPNB Earthquakes Occurrence).

In the following paragraphs, we describe the significant damage elements, although more than one effect coexist at several points, that is, a set of fractures associated to major collapse and human skeletons trapped under the fallen structures. In general, the observed fractures appeared to the excavators as well-preserved open elements while removing the fillings. No calcification of the fracture was observed to be prevented by the climate of the Jericho area. The fractures did not result from lateral spreading because

- the weight loading the fractured layers is not so high

- the observed fractures are always accompanied with other features in an extended deformed area

- most of them occur in the flat central sector of the Tell.