Jerash Propylaea Church

Jarash Propylaea Church

Jarash Propylaea Church

click on image to open in a new tab

Reference: APAAME_20080918_DLK-0146

Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

- from Chat GPT 5.1, 17 November 2025

- sources: Brizzi et al. (2010), NIP Project

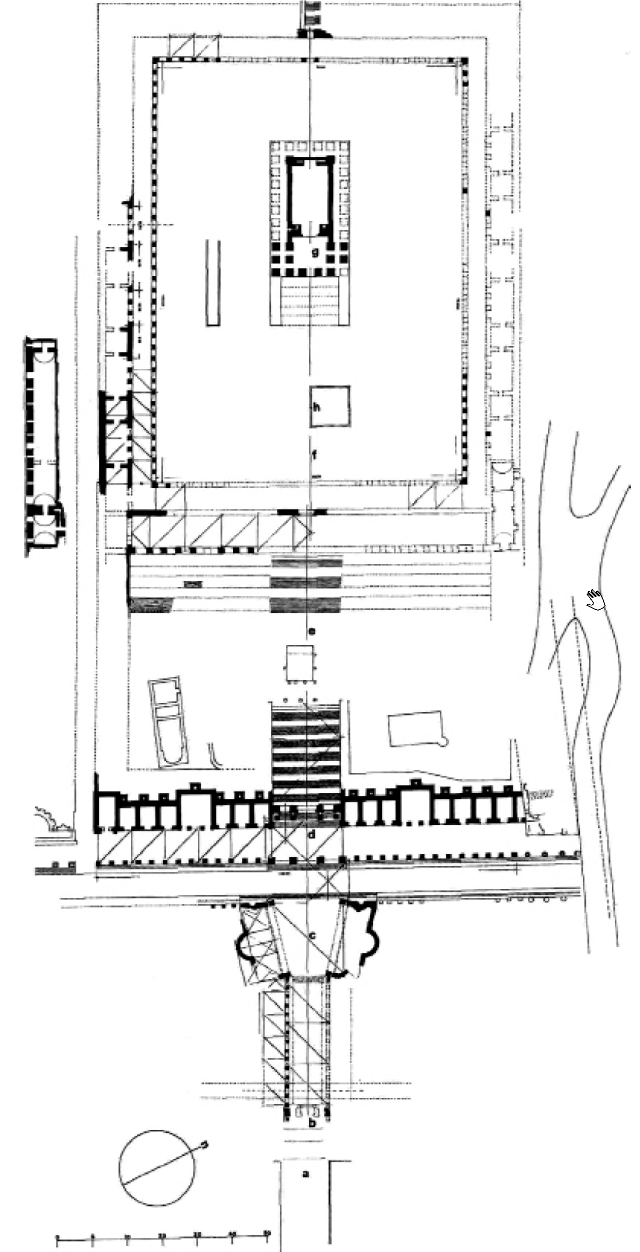

- Fig. 1 Plan of the sancturay of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

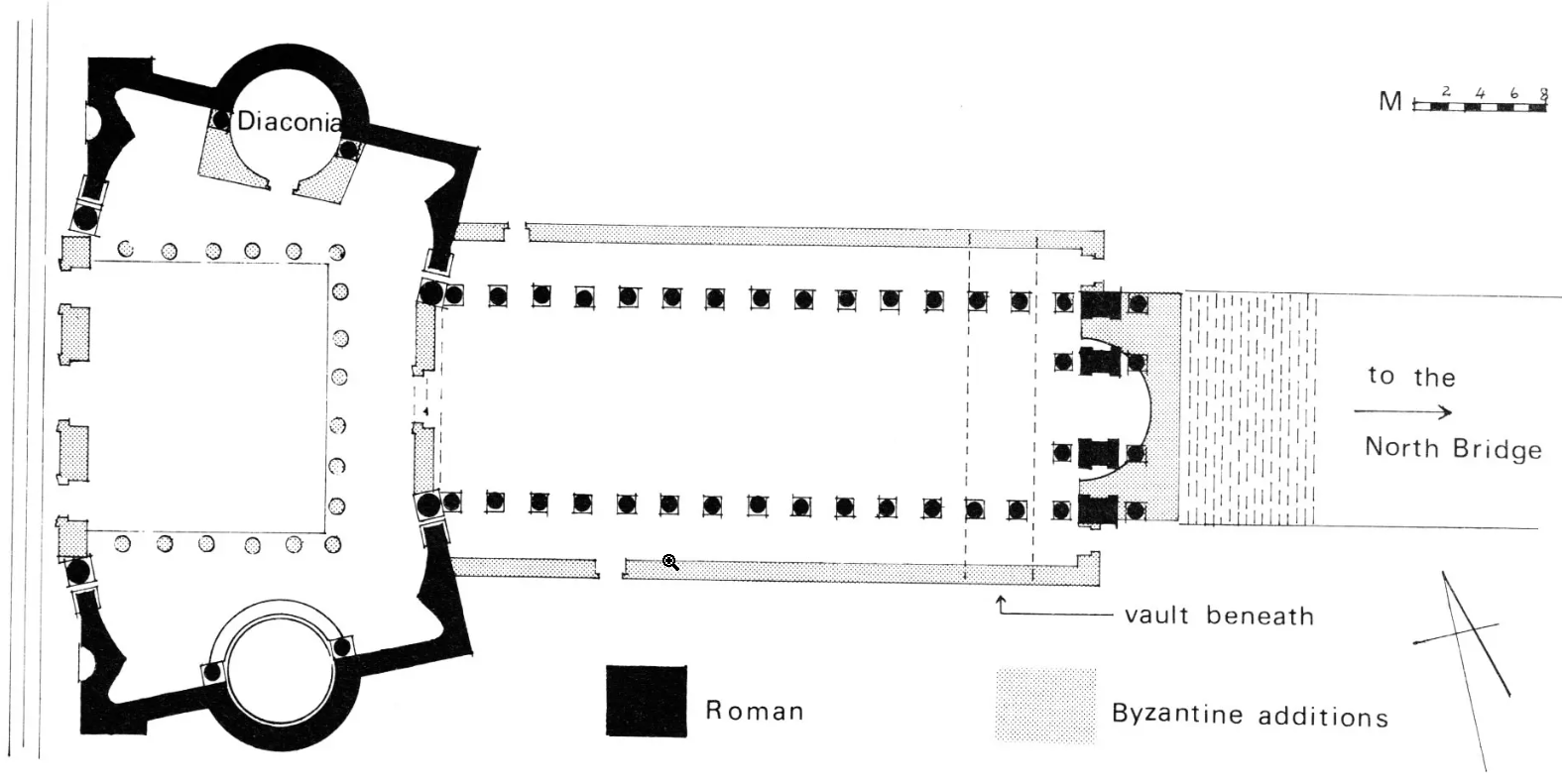

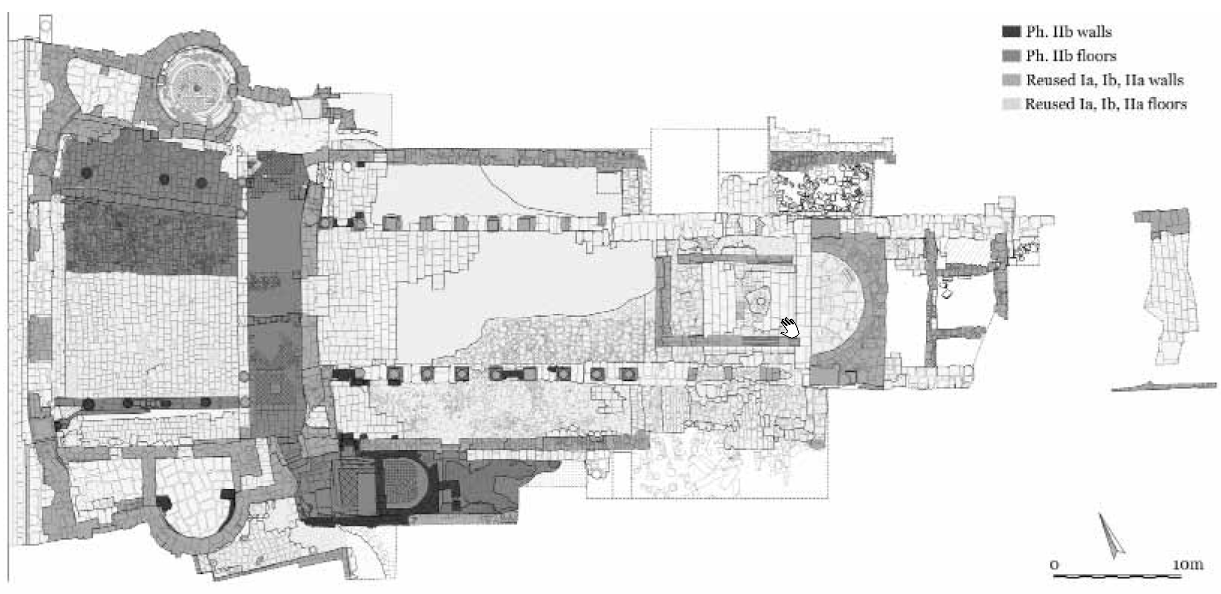

- Plan of the Church

of the Propylaea showing Roman and Byzantine phases from NIP Project

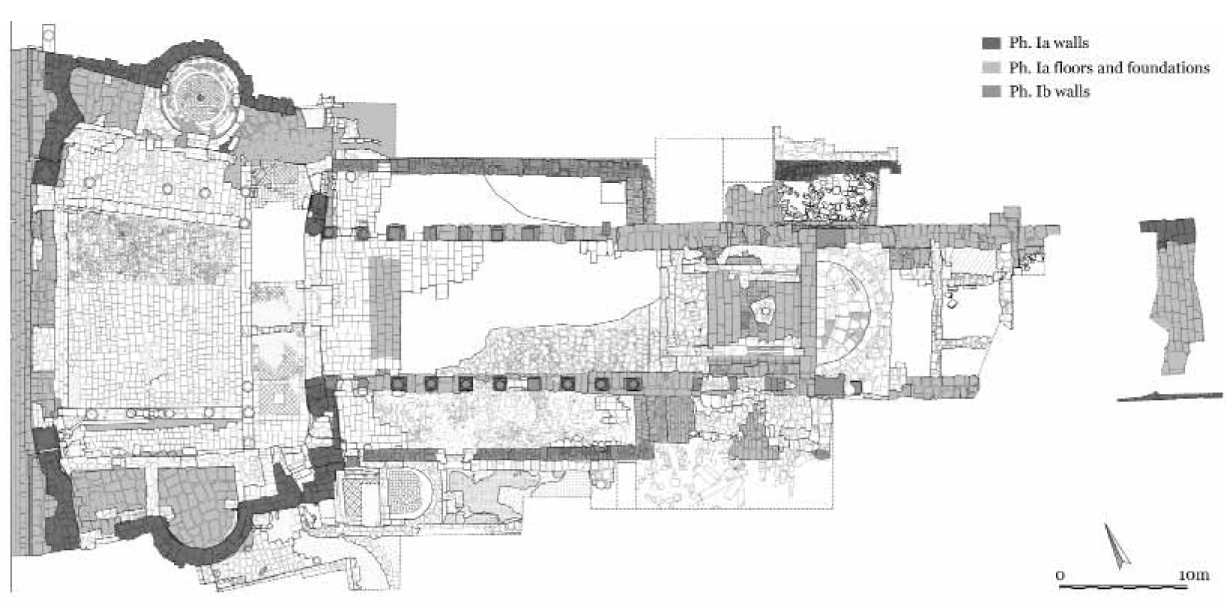

- Fig. 2 Multiphase plan

of the area of East Propylaeum of the Sanctuary of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

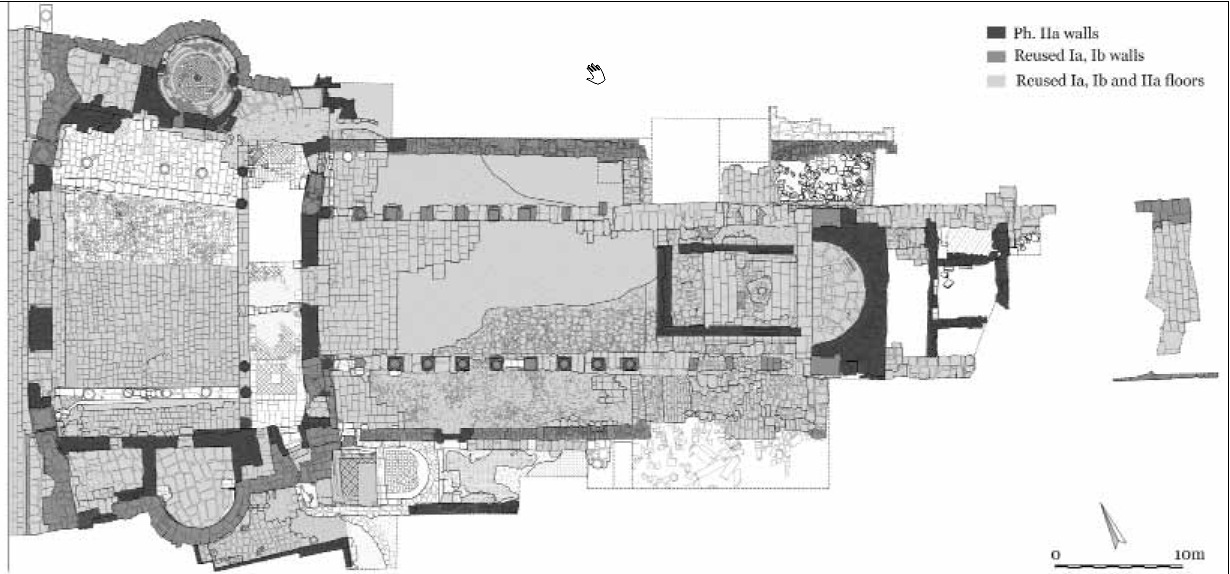

- Fig. 4 Phase 2a plan

the `Propylaea Church' complex from Brizzi et al. (2010)

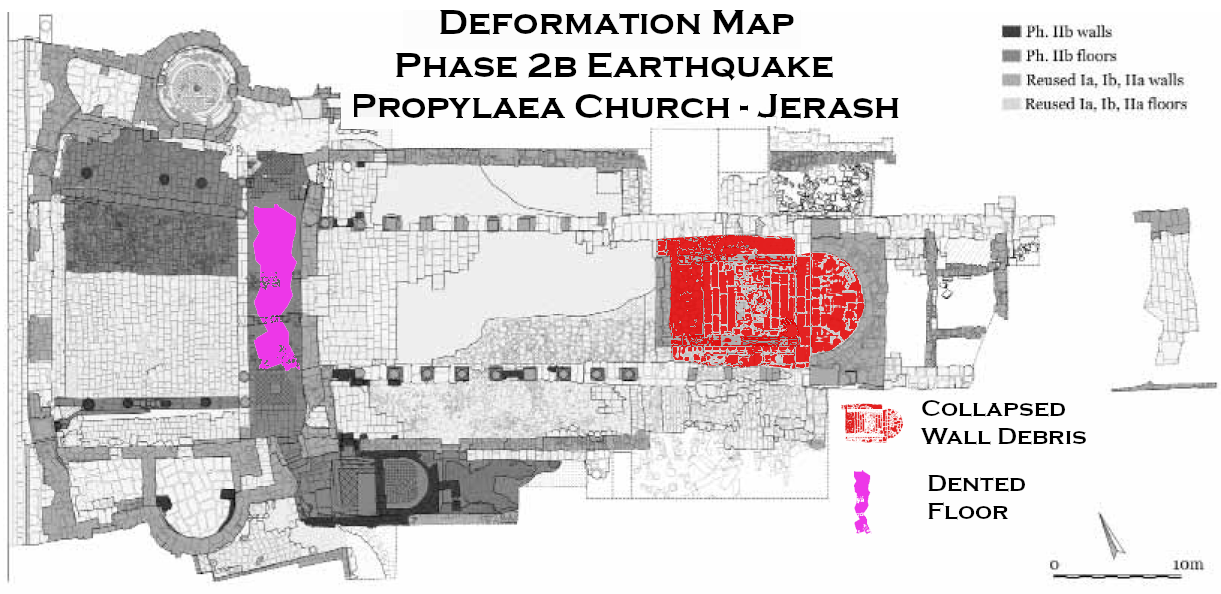

- Fig. 7 Phase 2b plan

the `Propylaea Church' complex from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 1 Plan of the sancturay of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Plan of the Church

of the Propylaea showing Roman and Byzantine phases from NIP Project

- Fig. 2 Multiphase plan

of the area of East Propylaeum of the Sanctuary of Artemis from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 4 Phase 2a plan

the `Propylaea Church' complex from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 7 Phase 2b plan

the `Propylaea Church' complex from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 9 Collapsed

debris in the presbiterium of the southern chapel from Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Fig. 9 Collapsed

debris in the presbiterium of the southern chapel from Brizzi et al. (2010)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Roman Imperial | mid second century CE | Urban redevelopment of the eastern approach to the sanctuary began with the construction of a bridge over the Chrysorhoas and the terracing of the natural slope. Two parallel walls of limestone blocks, about 10 m wide and 25 m long, defined a roadway that climbed the steep slope of Wadi Jarash. A paving of thick limestone slabs, placed at right angles to the walls, sealed the earth-and-stone fill of the bridge visible along the eastern edge. Halfway up the slope a north–south terrace wall in limestone cut the side of the bridge and created a second terrace suitable for building east of the colonnaded street. Westwards, a barrel-vaulted tunnel, 4.2 m wide, terraced the slope and kept open a cross-route beneath the future church nave. |

| 1b | Roman Imperial | second half of second century CE | Completion of the road between the bridge and the trapezoidal square. Portico colonnades were added along the first stretch of road after the bridge. Two limestone ashlar walls, about 4 m from the road, delimited the carriageway to north and south, running c. 23 m eastwards from the trapezoidal square. East of these, three vaults formed the basement of the ambulacra flanking the road. Part of the original paving, in regular limestone slabs, is preserved on the extrados of the tunnel vault, with a U-shaped channel cut into the slabs along the southern, eastern and northern edges of the road, indicating a drainage system and suggesting roofed porticoes. A restoration in the north-eastern corner of the northern ambulacrum, dated by pottery to the early third century CE, provides a terminus ante quem for this arrangement. |

| 1c | Roman Imperial | early third century CE | Construction of the east propylaeum. The foundations of a triple triumphal arch cut the earlier bridge walls about 15 m west of the terrace wall, demolishing the previous structure. Two external pillars are partially preserved, with three lower thresholds for double doors between them. The lateral openings had fasciated frames with rectangular niches or windows above. Nine reused voussoirs in the church apse likely belonged to the arched central portal with a span of c. 4 m. A pedestal in the eastern side indicates four projecting columns. Pedestals for two rows of columns, identical to those of the propylaeum, were cut into the old road walls, creating colonnades that flanked the road. Standardized Corinthian orders with late-Severan capitals decorated both the propylaeum and the colonnades, dated by stratigraphy and architectural style to the early third century CE. |

| 2A | Byzantine | mid sixth century CE | In the Byzantine period the whole area was transformed into a religious complex: a church erected on the site of the propylaeum, a colonnaded roadway, and buildings arranged around an atrium occupying the former trapezoidal square. The colonnaded roadway was roofed to create a central nave, 38.50 × 10.80 m, |

| 2b | Byzantine | late 6th–early 7th century CE |

Renovations reshaped the religious complex, adding new

northern and southern porticoes to the atrium, raising floor

levels, renewing pavements, and modifying internal rooms.

A coin of Phocas provides a firm terminus post quem for

this phase. The southern hall was converted into a small single-nave chapel with a semicircular apse, mosaic pavements, and stone altar bases. Adjacent rooms were repaired or reused, including a hall with a roughly restored mosaic and a storeroom with vessels and steps. Water installations were updated with terracotta pipes and a reused column drum as a fountain spout holder. Toward the end of this phase the complex suffered seismic destruction, seen in collapsed blocks across the presbyterium mosaic, cracked stone tiles in the eastern portico, and structural failures consistent with a strong earthquake. Lime heaps on the church floor may reflect aborted restoration following earthquake damage. Possible earthquakes include those of 633, 659, or 660 CE. |

| 3 | Umayyad / Early Islamic | 7th–8th century CE |

After the final Byzantine renovations, the entire complex

was reused informally. Floors were no longer maintained,

rooms were subdivided with rough walls, earlier mosaics

were covered with beaten-earth surfaces, and domestic

installations such as hearths and storage pits appeared.

Pottery from this phase includes Umayyad common wares,

cooking vessels, and lamps, along with residual Late Roman

and Byzantine material. Architectural collapse from the preceding period remained visible: large wall blocks and architectural fragments lay embedded in occupation layers, and several rooms show evidence of reused rubble derived from earlier seismic damage. No organized rebuilding occurred. Near the end of Phase 3 the complex experienced additional structural failure. |

| After Phase 3 | 8th–19th century CE |

The earthquake of 749 AD destroyed most of the standing structures and made the whole area unusable.

In contrast with other areas of the site, no Abbasid pottery was found here, and no other finds

earlier than Mamluk have been recorded in the excavations. In the mid 13th century the pottery is

associated with various traces of campfires and occasional pens and shelters for animals. Concomitant with the arrival of Circassian refugees in 1878, was the practice of the reuse of building material and robbing from the ancient monuments In the area of the `Propylaea Church' there is evidence of a systematic robbing of the stone slab paving from east to west. It is possible that this spoliation was done in the first years of the 20th century and was resumed for a short period after 1934, the year of the last season of the American expedition. |

... The end of the use of the church complex has been related to the evidence for a seismic event well documented in the chapel. Here some of the collapsed blocks have been found still in situ on the mosaic of the presbiterium (Fig. 9). Before the reoccupation, the debris was only partially removed, possibly just for rescuing the liturgical furniture. Evidence of collapsed structures has also been recorded on the floor of the eastern portico of the atrium, where the stone tiles preserved an unmistakable cracking by pointing shots.

In the church, the last activities before the addition of a packed-earth floor, might be identified with the decommissioning of the church; these are three building-lime heaps found on the paving of the church in the south-western corner of the southern aisle. This evidence suggests either that some works of restoration were begun in the church and never completed, or that, after the earthquake and the abandonment of the church, new owners restored the building just to use it as a storage facility, or for similar purposes.

In the southern edifice of the atrium a gap in the occupation of the rooms has been recorded. Layers of eolic sand, indicating a period of abandonment, were noted in many cuts made for Byzantine structures before the reoccupation documented by new floors and features in each room.

The earliest ruinous seismic events in the region, following the first decade of seventh century, were recorded in September 633 AD, followed by two events in 659 AD and 660 AD (Russel 1985: 46–47).59 We can assume that the church complex was suffered collapse brought about by one or more of the three earthquakes and, perhaps after an initial attempt to restore the function of the church, the whole complex was converted for different use.

59. We cannot definitely exclude localised earthquakes not recorded in known sources.

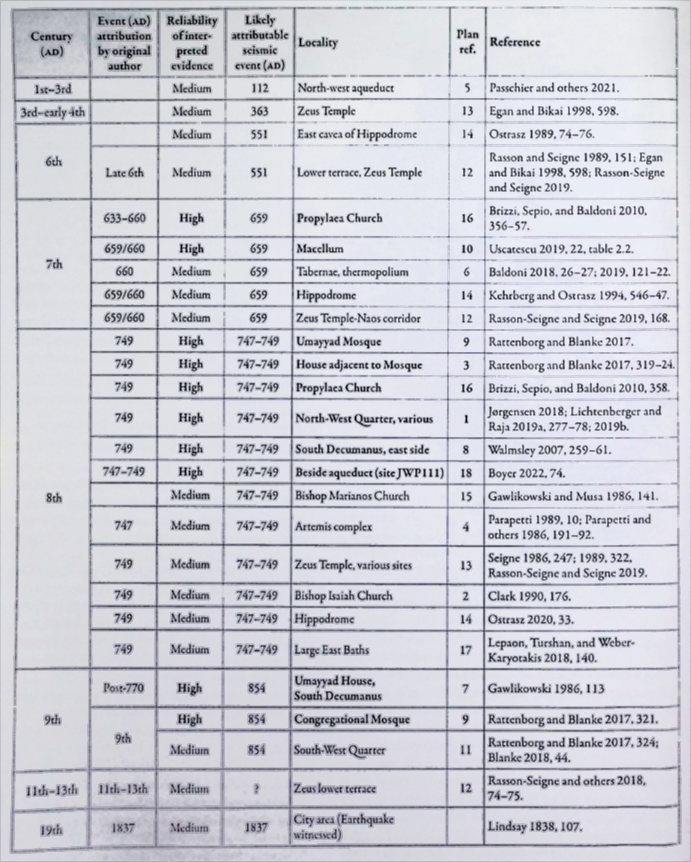

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th | 633–660 | High | 659 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 356–57. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 358. |

The contexts and the structures belonging to the Umayyad period were systematically ignored and removed from the area without documentation in the excavations from 1926 to 1934. In these conditions it is difficult to reconstruct the sequence for the whole area when only isolated pockets of in situ material can be documented for this period, and primarily only in the recently investigated area.

After the desecration of the church and the despoliation of the whole complex, partially ruined by a seismic event, the area was probably divided into different functional purposes.

The southern part of the church and the chapel were incorporated into the property belonging to an unexplored residence south of the excavation area60. In the chapel the debris was razed and sealed by a packed-earth floor, extended to the southern aisle of the church. Finds from these pavements can be dated to the seventh century AD. It is likely that these areas were covered by provisional shelters relying on standing structures of the earlier phase61. The side door of the aisle and the corridor to the atrium were closed by limestone blocks. Benches in reused collapsed elements were set in the area of the chapel. A fireplace and a tabun were found adjacent to the external wall of the southern exedra, where reused marble and limestone slabs paved an open area. At the moment of the earthquake of 749 AD (Tsafrir-Foerster 1992; Ambraseys 2005) the area of the chapel and of the southern aisle were occupied by at least twenty large grey ware basins, containing a white powder rich in calcium carbonate, probably marble dust prepared for decorations in stucco or plaster coatings. A similar array has been found in the north-western corner of the northern aisle, including a packed-earth floor covering the whole area, a tabun and a bench abutting onto the western wall of the church.

Scarce evidence of this phase has been left in the nave. In the eastern portico of the atrium the passage to the surviving main gate of the church was cut off by two small walls. This gave open access from the court to the nave, which was perhaps partially reconverted to a passageway.

In the southern edifice the rooms on the ground floor, the original pavements were replaced by packed-earth floors. In the central room a tabun was found together with a small structure for storing pots. The upper floor collapsed in this room before the 749 AD and the debris was never removed, but in the western room benches reusing architectural elements from this collapse were documented.

The porticoes of the atrium were partitioned by crosswise stone walls. In the gallery of the southern one, the stone paving was removed and substituted by a packed-earth floor. The colonnade was blocked up by walls in small limestone blocks bound together with earth mortar. In the western corner, several pit kilns have been documented in this phase. On the plaster of the northern wall of the edifice, close to the painted supplications described in the phase 2b, a graffito inscription in Kufic letters mentions a supplication to Allah.

In the gallery of the eastern portico a sequence of packed-earth floors covers the Byzantine stone tiles. Besides the two walls mentioned above, a third wall was built south of the northern side door of the church, which had been transformed into a niche. In the southern half, two taban have been found in different levels and, in the south- eastern corner, a square platform in stone and earth, 2.45 × 2.85 m and 30 cm high, was built for an unknown purpose.

The subdivision of the roofed areas and the spread of the tabun fireplaces in almost every unit are more appropriate for the putting in place of numerous workshops or shops than that of a permanent dwelling. Despite the gaps in the documentation of the area in this phase, a general view of the investigated contexts suggests that the court of the atrium maintained in this phase its connection with the colonnaded street and became again a public area where several artisans and merchant shops occupied the three galleries of the porticoes and the two edifices.

60. The northern wall of this building has been dug up.

This structure collapsed northwards in the mid 8th-century

earthquake and fine polychrome plaster fragments, glass vessels

and a stucco wall-lamp have been found in the debris.

61. There are no tiles in the aisle in the debris of the mid 8th-century earthquake,

nor of the Byzantine roof nor of any reconstructed covering.

The earthquake of 749 AD destroyed most of the standing structures and made the whole area unusable. In contrast with other areas of the site, no Abbasid pottery was found here, and no other finds earlier than Mamluk have been recorded in the excavations. In the mid 13th century the pottery is associated with various traces of campfires and occasional pens and shelters for animals.

Concomitant with the arrival of Circassian refugees in 1878, was the practice of the reuse of building material and robbing from the ancient monuments.62 In the area of the Propylaea Church there is evidence of a systematic robbing of the stone slab paving from east to west.63 It is possible that this spoliation was done in the first years of the 20th century and was resumed for a short period after 1934, the year of the last season of the American expedition.

62. It lasted legally until 1946, when it was banned during the British mandate in Transjordan.

63. An iron lever was found in the first preserved eastern row of slabs.

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th | 633–660 | High | 659 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 356–57. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 358. |

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Propylaea Church

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

Fig. 9 |

|

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Propylaea Church

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 7 of Brizzi et al. (2010)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Propylaea Church

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

Fig. 9 |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Propylaea Church

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

|

|

Brizzi, M., Sepio, D., & Baldoni, D. (2010). Italian excavations at Jarash 2002-2009: The area of the East Propylaeum of the Sanctuary of Artemis and the “Propylaea Church” Complex

. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, 54, 345-370.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

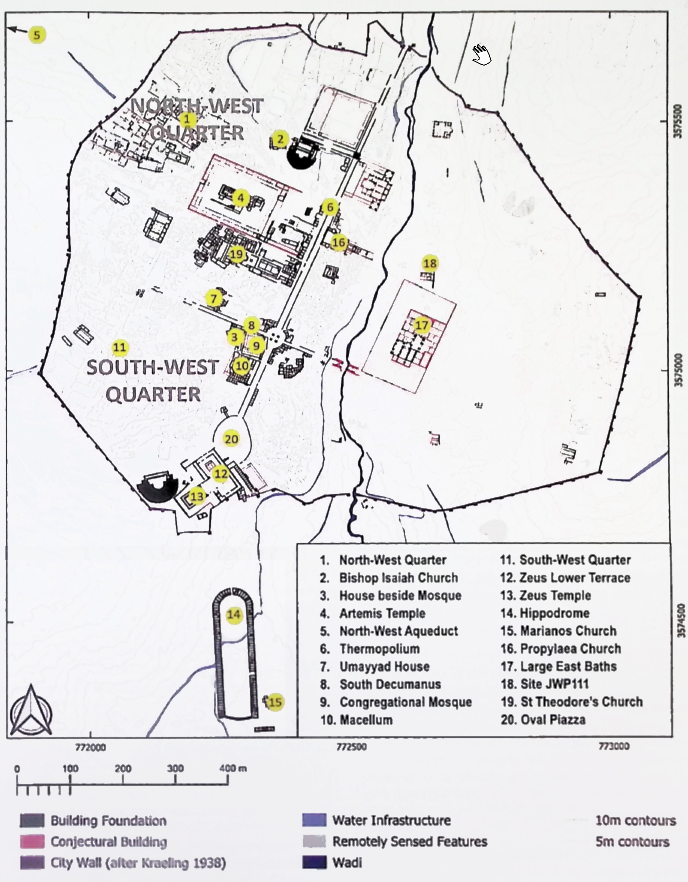

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)