Jerash Northwest Aqueduct

Jerash Northwest Aqueduct Sampling Sites

Jerash Northwest Aqueduct Sampling Sitesclick on image to explore this site on a new tab in Google Earth

ChatGPT Introduction

- from Chat GPT 5.1, 17 November 2025

- sources: Boyer (2022)

Aerial Views, Plans, Profiles, and Thin Sections

Aerial Views

Plans

Normal Size

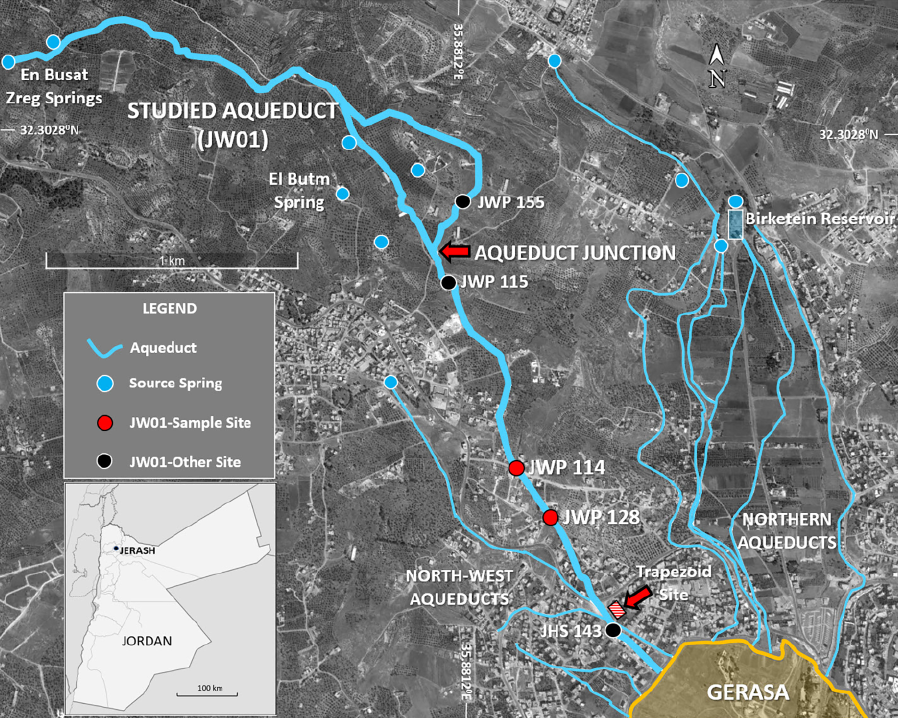

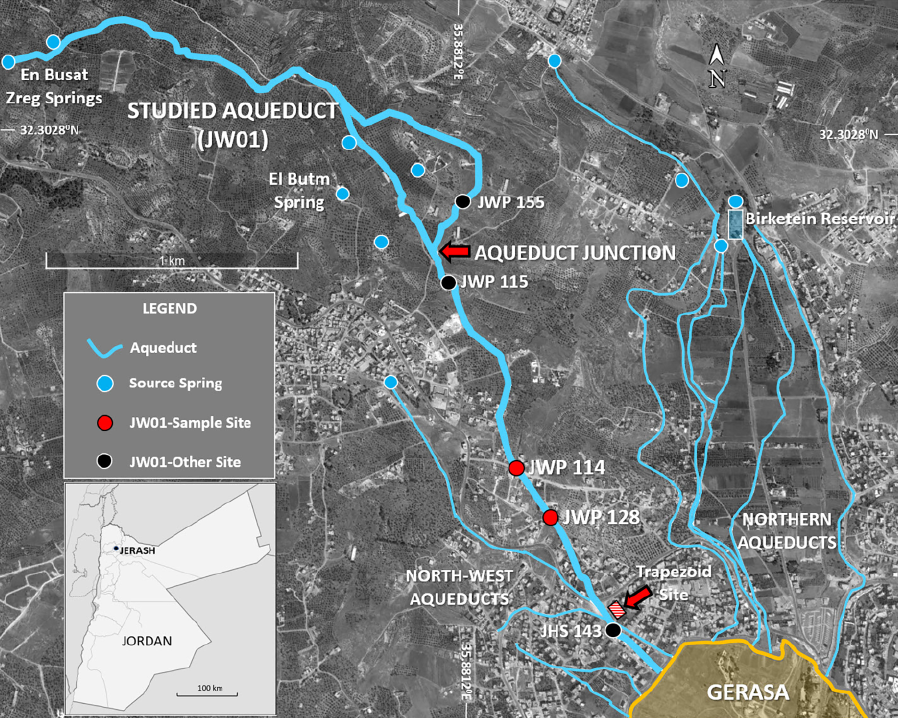

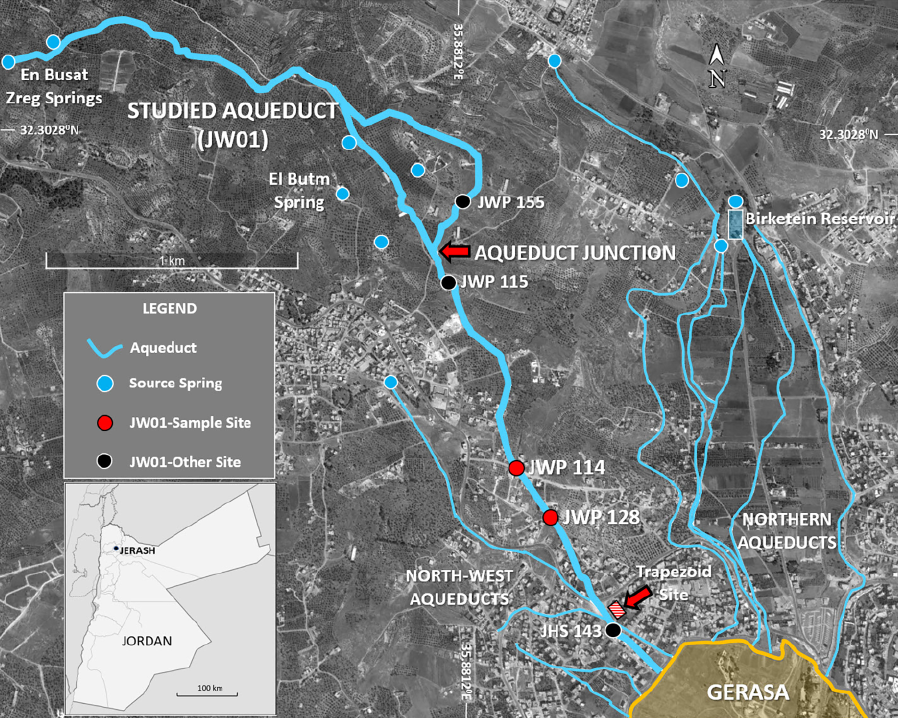

- Fig. 1 Northern and

North-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs from Passchier et al. (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

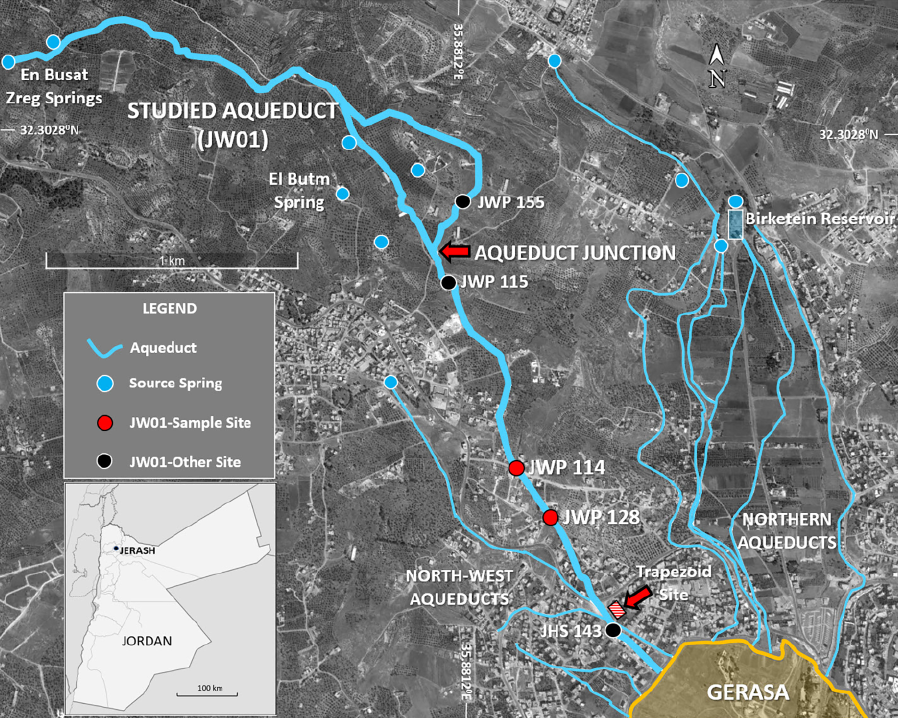

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Passchier et al. (2021)

Magnified

- Fig. 1 Northern and

North-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs from Passchier et al. (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The northern and north-western aqueduct networks of Gerasa and the inferred supply springs that delivered water to the north-west quarter of the city. The bold orange line marks the city wall. Aqueduct JW01 (bold blue line) is the subject of this study. Sites mentioned in the text and carbonate sampling locations are indicated.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Passchier et al. (2021)

Profile

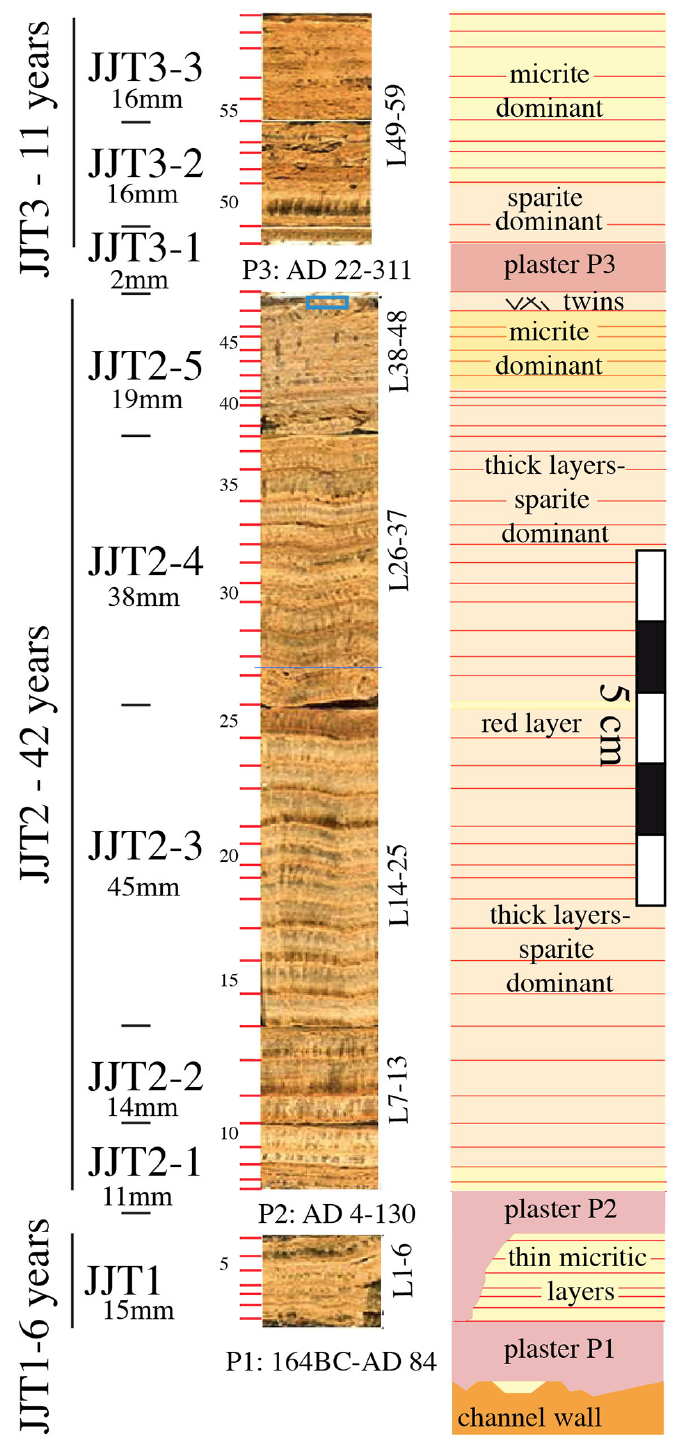

Figure 3

Figure 3

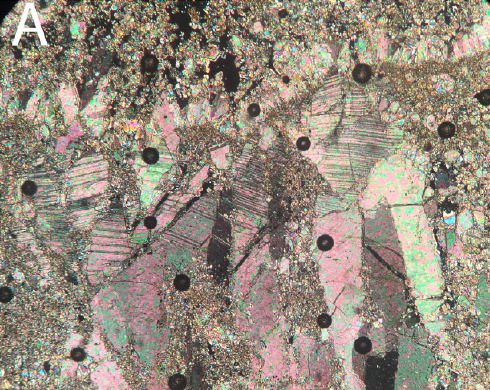

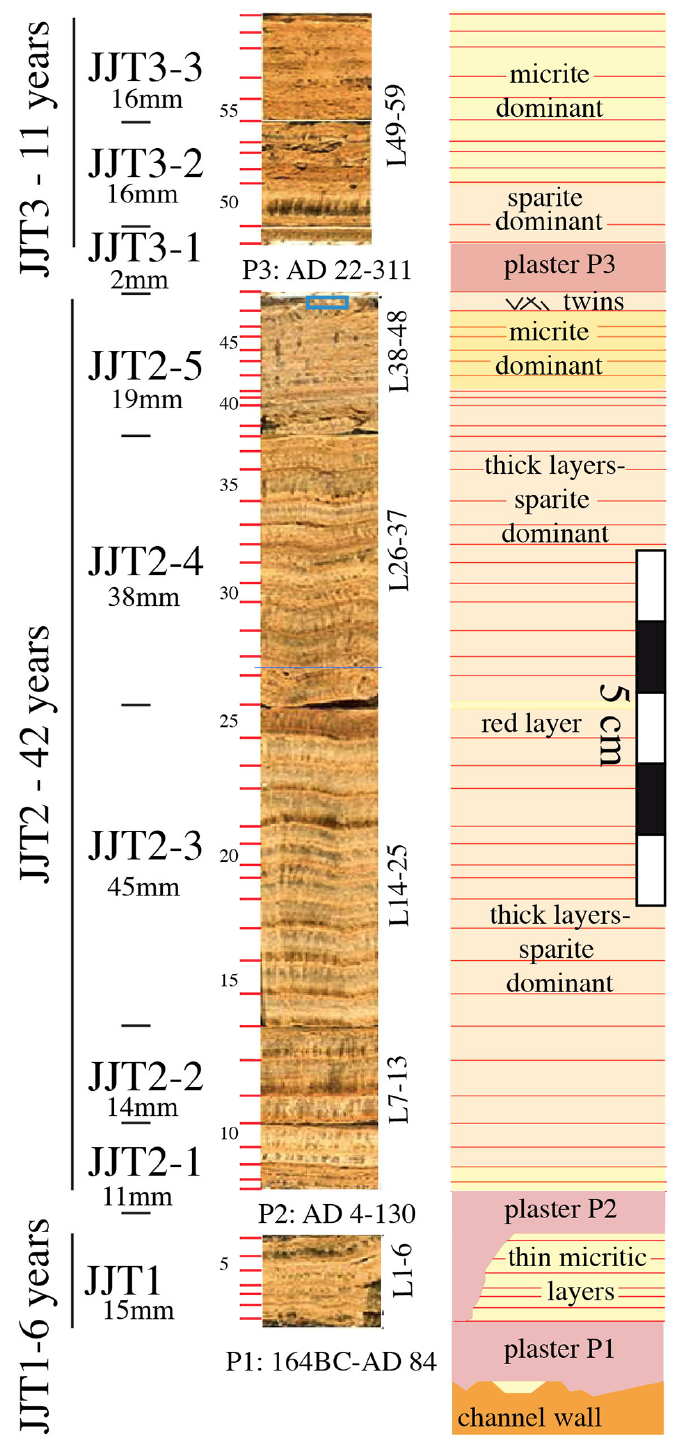

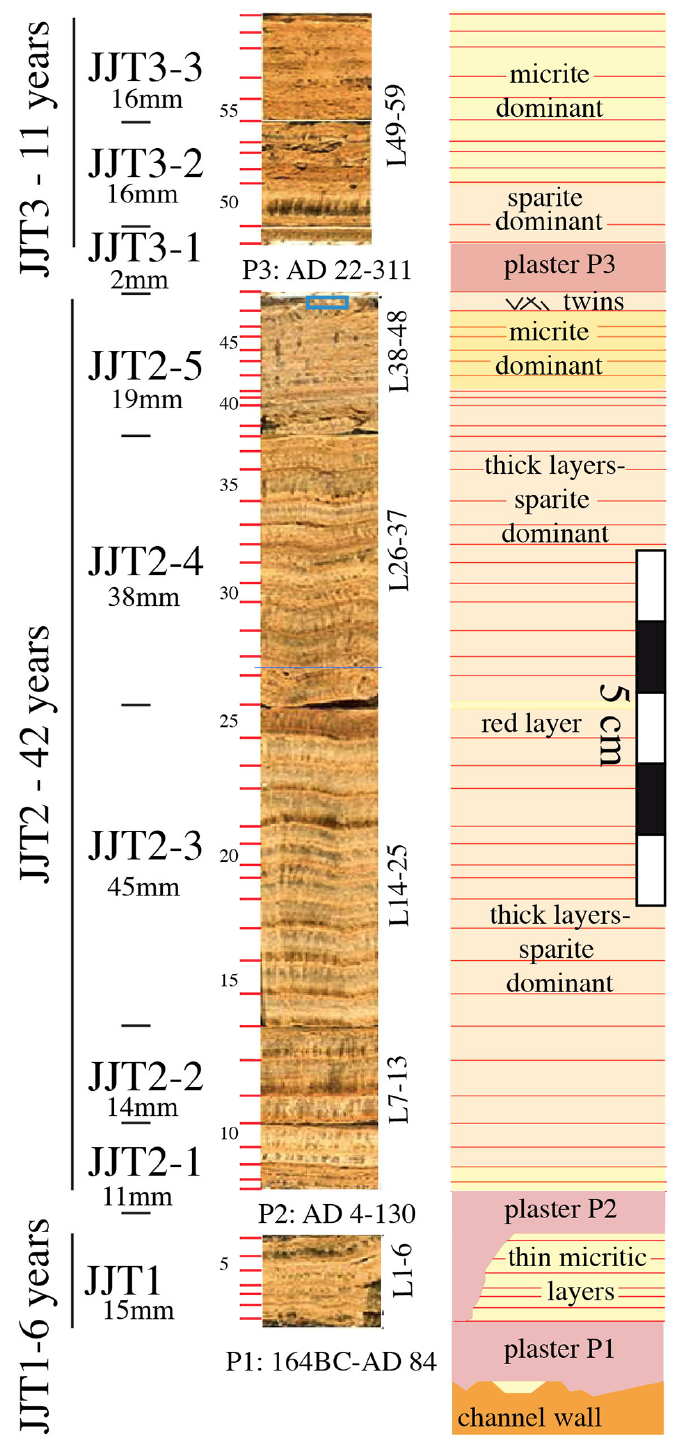

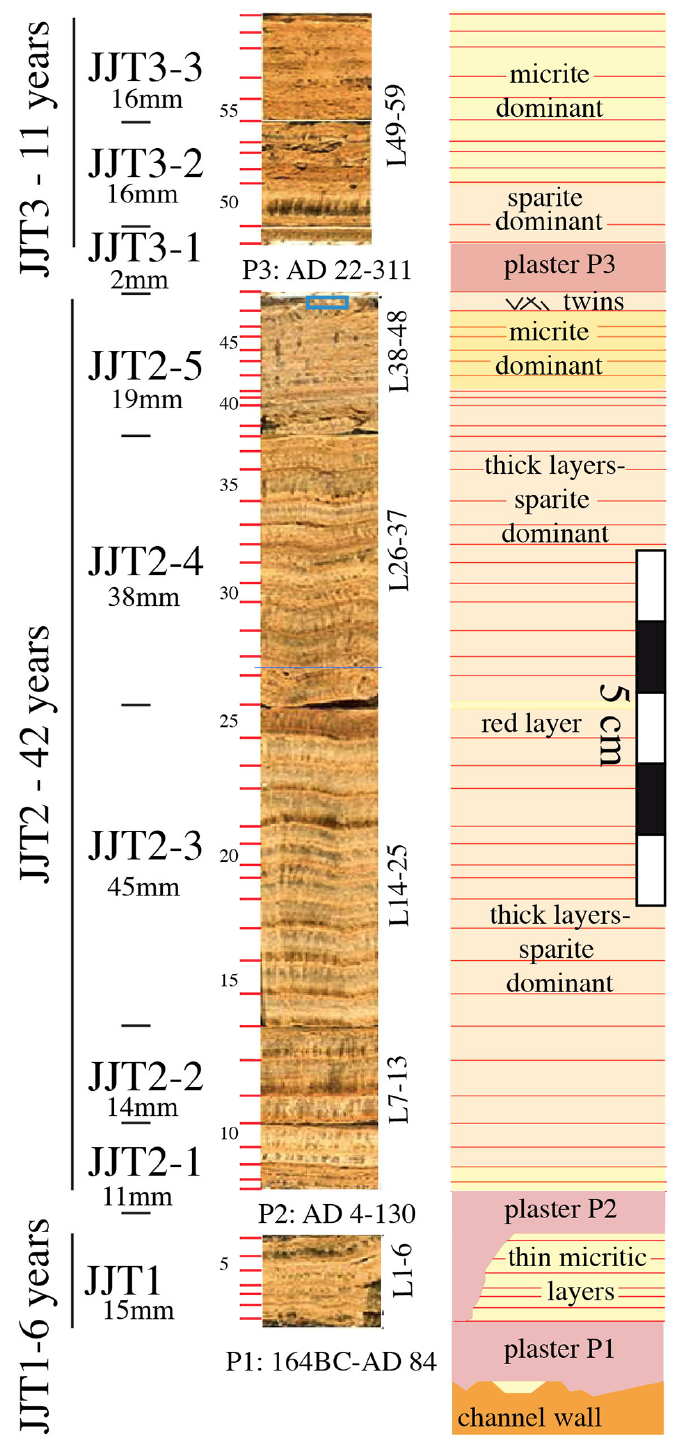

Stratigraphy of carbonate deposits from the Jerash aqueduct, shown as polished slabs (left) and fabric aspects (right). There are three depositional sequences (JJT1 to JJT3) separated by plaster. Boundaries between layers are marked by red lines. In layer L48 deformation twins are present in calcite crystals [JW:earthquake]. Calibrated radiocarbon dates from Boyer (2019).

click on image to open in a new tab

Passchier et al. (2021)

L48 Earthquake - 22-311 CE

Discussion

Passchier et al. (2021)

Abstract

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) deposits from aqueducts are an innovative archive to obtain local high-resolution palaeoenvironmental and archaeological data in interdisciplinary studies. Deposits from one of the aqueducts of the Roman city of Gerasa provide a record of 59 years during the 1st to 3rd centuries AD, divided into three sequences separated by plaster layers. Annual carbonate layers show an alternation of sparite, formed in winter, and micrite, formed in summer. Brown bands at the base of many sparite layers probably correspond to large rainstorms in early winter. A fine lamination present in the brown bands may be aeolian in origin. Stable isotope and trace element data confirm annual layering, indicate strongly variable flow rate in the aqueduct, and show truncations that may have been associated with drying up of the channel in some years. The trace element pattern is typical of a relatively small aquifer with a rapid response to precipitation. The trace element composition changes abruptly from the first to the second carbonate sequence, suggesting that a spring was added to increase the flow rate. Deformation twins in calcite crystals at the top of the second sequence may be due to earthquake damage after 48 years of use. The presence of abundant clay in the carbonate sequence, especially in the third sequence, suggests earthquake damage to the channel. The channel was usually replastered after damage. The aqueduct went out of use sometime after the mid-2nd to mid-3rd century AD. The carbonate archive stores key information on groundwater quantity and composition and indirectly on air temperature, rainfall, extreme environmental events, and land use at sub-annual resolution.

2.1 Gerasa aqueducts

Gerasa had a network of more than ten aqueducts providing water to the north-west part of the city from extramural karst springs in Roman Imperial times (Fig. 1; Boyer, 2016; 2019; Stott et al., 2018). Recent construction has erased most traces of these aqueducts close to the city, but they can be reconstructed from ground surveys and aerial photographs (Stott et al., 2018). We focussed on JW01, the largest and best-preserved aqueduct, exposed at several locations, mostly as a rock-cut channel that was at least partially covered by capstones (Fig. 1; Boyer, 2019). It derived its water from springs to the north-west supplied from Upper Cretaceous limestone aquifers (Hammouri and El-Naqa, 2008; Boyer, 2018; 2019): this includes the springs of En Busat Zreg (32.30577° N, 35.86196° E - Fig. 1) and probably Fauwara (32.31257° N, 35.85077° E) and Mafthasil (32.31706° N, 35.83869° E) to the west. The average gradient of sections of the aqueduct varies from 3.6% to 21% (Boyer, 2019), leading to a locally high flow velocity (Supplementary material S2). The aqueduct was dated using 14C AMS of charcoal in plaster and was likely in use between the 1st century BC/1st century AD and the early 3rd century AD (Supplementary material S3; Boyer, 2019).

3. Materials and Methods

Aqueduct conduits are labelled with a prefix that reflects the wadi in which they lie and whether they occur on the east or west bank. A JW prefix, therefore, shows that the conduit is on the west bank of Wadi Jerash. Carbonate from JW01 was sampled at two sites (Fig. 1). The best-preserved site JWP128 was a road cut at 32.28935° N, 35.88449° E, sampled in 2014 and presently covered by a wall (Figs. 2a and b). A series of samples were taken covering the entire stratigraphy and the plaster layers. A second sample was taken 180 m upstream from JWP128 at site JWP114 (32.29073° N, 35.88449° E). It corresponds to part of the JJT2 stratigraphy of JWP128 (Figs. 2c and d). Selected fragments from JWP128, labelled JJT1, JJT2-3 and JJT2-4, and JJT3-2 (Fig. 3) and sample JJT-NC from JWP114 were cut in half using a diamond saw. One of these slabs was used for analytical work, the other to prepare polished and covered thin sections. The microstructure of the thin sections was investigated by transmitted-light microscopy at the Microstructure Laboratory at the Johannes Gutenberg University (JGU) in Mainz. Calcite twins and their displacement sense were analysed in covered thin section using a U-stage on a petrographic microscope.

4. Results

4.1 Petrography

The sampled carbonate stratigraphy of JWP128 consists of three sequences labelled JJT1–3, separated by layers of grey plaster (Figs. 2b and 3). Thin sections show a rhythmic sequence of similar layers of variable thickness (Figs. 3–5), each with an alternation of micrite and elongate columnar sparite crystals. Micrite and microsparite crystals are 2–10 μm in diameter, while sparite crystals can be up to 2 mm wide and 7 mm long. The alternation of micrite/microsparite and sparite, in combination with stable isotope cycles, allows counting of annual layers (L1–59; Figs. 3 and 4).

The start of each stratigraphic segment JJT1–JJT3 consists of a continuous band of micrite, deposited directly on the plaster (Figs. 3 and 4). Columnar sparite crystals grow from these micrite horizons, commonly in fans due to growth competition (Passchier et al., 2016b; Fig. 5). Micrite commonly forms a band of serrated shape between sparite layers (Fig. 5). Sparite crystals contain bands of brown coloration (hereafter “brown bands”), which show the shape of the calcite growth surface. At high magnification, they are composed of numerous thinner laminae, 6–10 μm apart (Figs. 5 and 6b–d). Small calcite crystals locally nucleate in these brown bands. Each macroscopic layer can be subdivided from bottom to top into microscopic sublayers of variable width as follows (Fig. 5): (a) micrite with initial sparite and upward tapering of micrite domains between sparite crystals; (β) sparite crystals with brown bands; (γ) pure sparite; (δ) initial and widening micrite domains with occasional brown bands in contemporaneous sparite; (ε) pure micrite, not present in all layers. The base of sublayer (a) was chosen as the boundary between layers (Figs. 3 and 4).

In hand specimen, sublayers (a) and (ε) are yellow, (β) is brown, and (γ–δ) grey (Figs. 3 and 5b inset). In (δ), micrite may be continuous, topping sparite crystal faces completely, e.g. in L25 (Fig. 5a). However, micrite mostly occurs as discontinuous horizons, interrupted by individual sparite crystals that extend over several layers (Fig. 5). The geometry of sparite varies from dense columnar and fan-shaped sparite to isolated crystals surrounded by micrite.

4.2 Microstratigraphy

In the rock-cut channel of JWP128, a basic plaster layer, P1, was installed on an eroded limestone surface and on thin remains of older carbonate deposits, which were either eroded by flow or were manually removed as part of cleaning processes (Fig. 3; Supplementary material S3). This implies that the aqueduct had been in use for some time before the sequence analysed here was deposited. In sequence JJT1, layers L1–5 are thin (mean thickness 2.5 mm) with a high percentage of micrite in continuous bands (Figs. 3 and 4). The uppermost layer L6 is dominated by sparite. JJT1 was eroded in the centre of the channel by a scour, which was filled with plaster P2 (Fig. 3). JJT2 is the most prominent sequence with a regular alternation of sparite and micrite in 42 layers. The initial layers are thin and similar to older deposits, but layers L9–38 are thick and regular in thickness and facies distribution. Layer L25 is distinguishable by its unusual red coloration in hand specimen (Fig. 3) and a thick, continuous flat layer of micrite at its top (ε in Fig. 5a). The uppermost layers of JJT2 are relatively thin and micritic (Fig. 3). Layer L48 contains deformation twins in the calcite, accompanied by broken crystals and fractures filled with micrite (Fig. 6a). This damaged zone is overlain by undeformed micrite, indicating that the damage occurred during deposition of carbonate (Fig. 6a), shortly before application of plaster layer P3 (Fig. 3). JJT2 also shows “orientation bands” parallel to the growth direction where sparite crystals have a deviant orientation, and neighbouring fans interact in a complex manner (Fig. 4: JJT2–3, JJT2–4). This was apparently induced by ripple-like irregularities in the growth surface of the layers, normal to the flow direction in the aqueduct. Similar ripple-like growth structures have been observed in other aqueducts (Motta et al., 2017; Sfirrelil Hindi et al., submitted). In JJT3, layering is relatively wide with extensive micrite, while only single layers (e.g. L50) are dominantly sparitic (Figs. 3 and 4). The sequence ends in layers of micritic carbonate (L55–59). Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the three plaster layers P1–P3 yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates (68% probability) ranging from the 1st century BC/AD to the early 3rd century AD (Fig. 3; Boyer, 2019; Supplementary material S3).

5. Discussion

Introduction

Carbonate from the Jerash aqueduct, with red colour banding of alternating sparite and micrite, is similar to that of many other Roman aqueducts in the Eastern Mediterranean, e.g. in Turkey and Israel. The observed carbonate is dense due to abundant sparite, which is common in covered aqueducts, particularly those with fast, supercritical flow (Şirmeli̇hi̇ndi̇ et al., 2013a, b; Passchier, 2016a). The aqueduct at the sampling sites has a steep slope between 19 and 21% giving a Froude number of 4.2–5.3, depending on water depth (Supplementary material S2). Other aqueducts with a gentler slope and slow, subcritical flow conditions contain dominantly micritic carbonate (Passchier and Şirmeli̇hi̇ndi̇, 2019). Aqueducts like JW01, with relatively thick annual layering and abundant sparite, are prime targets for paleoenvironmental investigation, since small-scale changes in carbonate deposition can reflect variations in palaeo-temperature, water composition and flow rate (Supplementary material S2). Fig. 9c–g shows a schematised summary of the microstructural, stable isotope and trace-element features described above.

5.5 Restructuring, floods, droughts, and earthquakes

Carbonate deposits in the Jerash aqueduct show evidence of restructuring and repairs, some probably in response to floods and earthquakes. Layers L1–8 are relatively thin and micritic, indicating low water levels and low flow rate with clay impurities (Figs. 3 and 8). An exception is L6, which has unusually low δ13C values (Fig. 7) and is followed by erosion of the channel and repairs including a new layer of plaster (P2) (Fig. 3, Supplementary material S3). Most likely, this was due to a flood event: since the slope of the aqueduct is 19–21% at the sampling site, erosion of the channel floor was a permanent risk at high flow rate. In contrast to JJT1, sequence JJT2 has generally thicker and more sparitic layers after L8 and low trace-element concentrations in the measured section L14–25, suggesting that the aqueduct carried more water with less suspended clay. This can be attributed to addition of a new spring or springs to create a higher flow rate starting with layer L9 (Fig. 3). JJT2 records the period with the highest mean flow rate of the aqueduct, even though in some years (L6, 19, 20, 25), the rate fell to alarmingly low levels in the dry season or water flow even stopped for some time (Figs. 7 and 8). The continuous micrite layer at the top of L25 may indicate such a low-flow period in response to a drought. Layers L37–48 are more micritic and thinner, possibly due to a damaged channel or a dry period (Fig. 3).

Layer L48 at the top of JJT2 has deformation twins in calcite (Figs. 3 and 6a) and the aqueduct was resealed with a plaster layer (P3) following L48. The twin orientations as observed using a U-stage indicate that they were formed by vertical pressure applied on the crystals. Possibly, this damage records the impact of a falling stone (Parlangeau et al., 2019), e.g. due to an earthquake.

In JJT3, the first two years (L49 and L50) represent a high flow rate as in JJT2. The following sequence has layers of micritic carbonate, with abundant clay impurities, indicating a significant change that persisted for years until the end of deposition. The presence of clay could be due to erosion and/or changing vegetation cover, but the sudden change, following a wide sparite-dominated layer (L50), rather suggests a sudden event. Possibly, an earthquake damaged the channel again, leading to low flow rate, without repair in subsequent years until the abandonment of the aqueduct. Observations at JWP128 suggest that the aqueduct went out of use sometime after the late 2nd to mid-3rd century AD. The carbonate deposits within the channel at location JWP128 are fractured, and this may reflect another seismic event.

6. Conclusions

- Microfabric, stable isotope and trace element data of carbonates from aqueduct JW01 indicate a pronounced seasonality in flow rate and water temperature, which corresponds with (modern) precipitation and air temperature in the study area, and with local spring characteristics. The pattern is typical of aqueducts in the Eastern Mediterranean, with strong intra-annual variations in δ13C and δ18O, dominated by winter rains.

- δ13C, P and Mg curves show an unusual saw-tooth geometry that can be explained by an abrupt increase in flow rate following winter rains, followed by a gradual decrease during the warm season.

- The succession of microfabric, stable isotope and trace element composition patterns argues for a small karst aquifer with a small storage capacity feeding this aqueduct. Aquifer size and characteristics must, therefore, be incorporated in interpretations of aqueduct carbonate.

- The aqueduct functioned for at least 59 years. There is evidence for restructuring after 8 years and for repairs and re-plastering after 6 and 42 years.

- Earthquakes may have been responsible for calcite deformation twins and some of the observed changes in calcite deposition and channel repairs.

Boyer in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

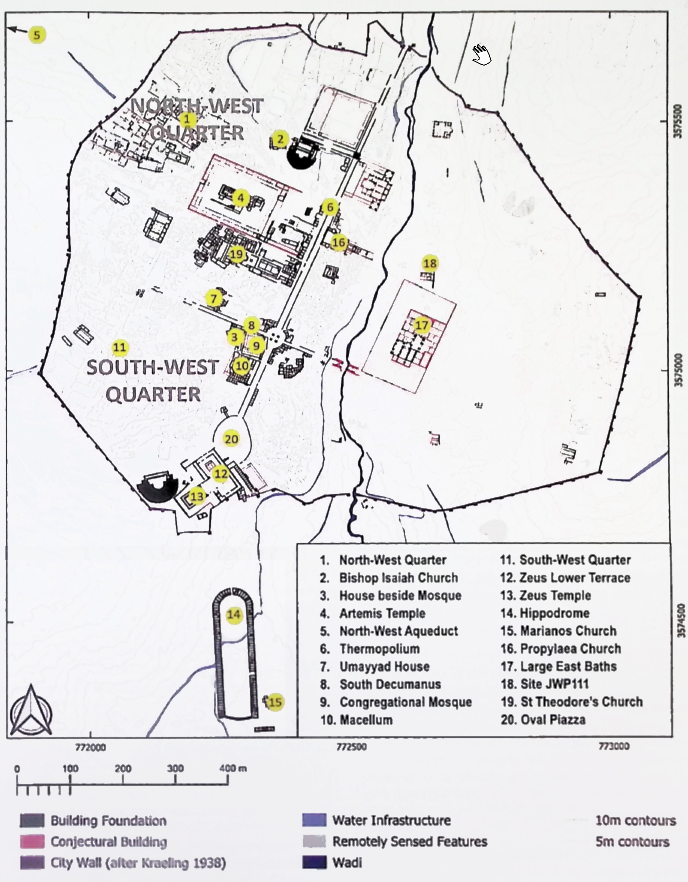

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st–3rd | Medium | 112 | North-west aqueduct | 5 | Passchier and others 2021. |

L48 Earthquake - 22-311 CE

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Northwest aqueduct Sampling Sites JWP114 and JWP 128 |

Fig. 6a Fig. 3

Figure 3

Figure 3

Stratigraphy of carbonate deposits from the Jerash aqueduct, shown as polished slabs (left) and fabric aspects (right). There are three depositional sequences (JJT1 to JJT3) separated by plaster. Boundaries between layers are marked by red lines. In layer L48 deformation twins are present in calcite crystals [JW:earthquake]. Calibrated radiocarbon dates from Boyer (2019). click on image to open in a new tab Passchier et al. (2021) |

|

L48 Earthquake - 22-311 CE

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects

from Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

-

Synoptic Table of ESI 2007 Intensity Degrees

from Michetti et al. (2007)

-

Environmental Effects vs. Intensity

from Michetti et al. (2007)

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Northwest aqueduct Sampling Sites JWP114 and JWP 128 |

Fig. 6a Fig. 3

Figure 3

Figure 3

Stratigraphy of carbonate deposits from the Jerash aqueduct, shown as polished slabs (left) and fabric aspects (right). There are three depositional sequences (JJT1 to JJT3) separated by plaster. Boundaries between layers are marked by red lines. In layer L48 deformation twins are present in calcite crystals [JW:earthquake]. Calibrated radiocarbon dates from Boyer (2019). click on image to open in a new tab Passchier et al. (2021) |

|

|

References

Articles and Books

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

Passchier, C., Sürmelihindi, G., Boyer, D., Yalçın, C., Spötl, C., & Mertz-Kraus, R. (2021).

The aqueduct of Gerasa – Intra-annual palaeoenvironmental data from Roman Jordan

using carbonate deposits. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 562, 110089.

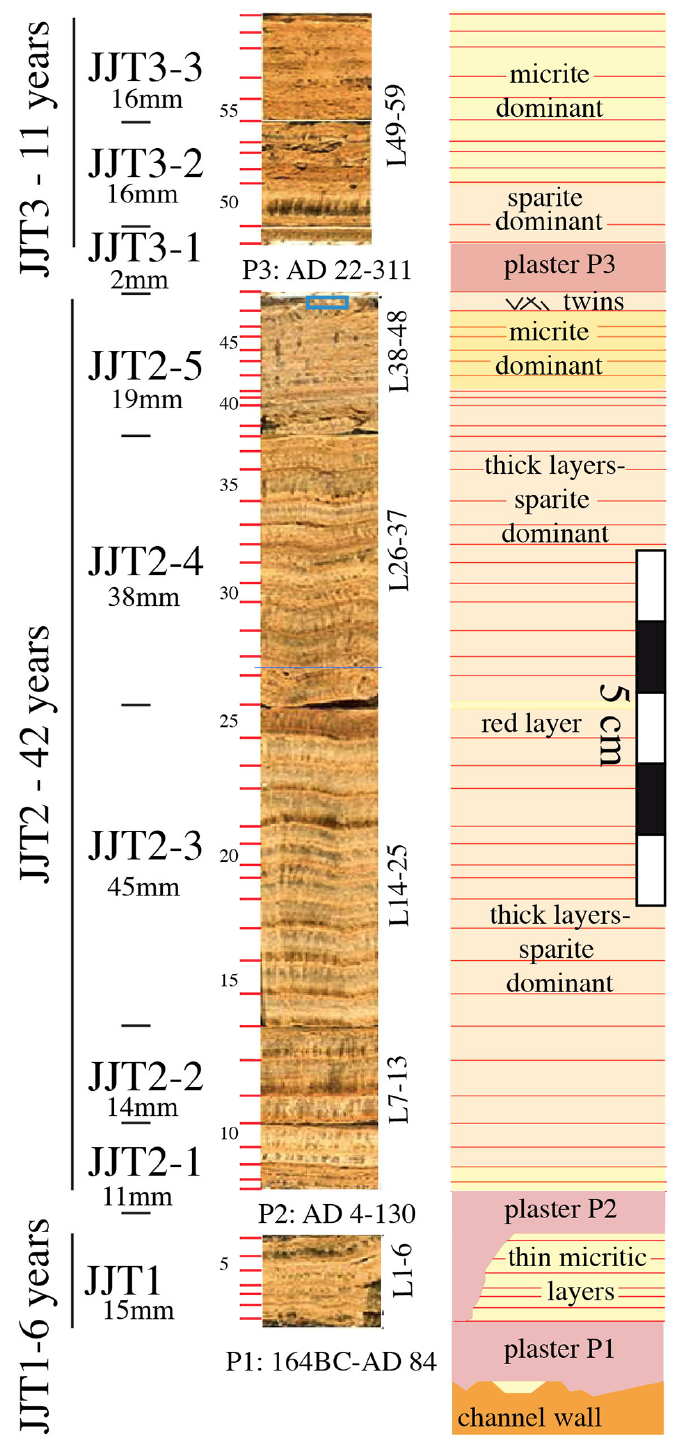

Earthquake Damage in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE

Map

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)