Jerash - Large East Baths

Jarash East Baths

Jarash East Baths

click on image to open in a new tab

Reference: APAAME_20080918_DLK-0154

Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

- from Chat GPT 5.1, 16 November 2025

- sources: Madain Project – Jerash, Jerash (Wikipedia), Universes in Universe – Jerash

The architectural programme followed the classical sequence typical of Roman thermae: large vaulted halls, hot and warm rooms heated by hypocausts, cold pools, service corridors, and associated palaestra spaces for exercise. The complex would have required a substantial and reliable water supply, drawn from the aqueduct system that entered the city from the east. The visibility of the bath complex from major approaches to the city suggests it also functioned as a civic statement—an architectural marker of Gerasa’s prosperity, urban sophistication, and participation in the cultural norms of the wider Roman Mediterranean.

Its placement near the eastern entrance of the walled city may have served both practical and symbolic purposes: locating a massive water-demanding installation close to the incoming aqueduct, while also providing an impressive public amenity for residents and visitors arriving from the east. The surviving remains—massive masonry walls, sections of vaults, pilae from the hypocaust system, and service passages—offer a clear impression of a grand, efficiently planned bathing establishment that operated for centuries as one of Jerash’s most important public institutions.

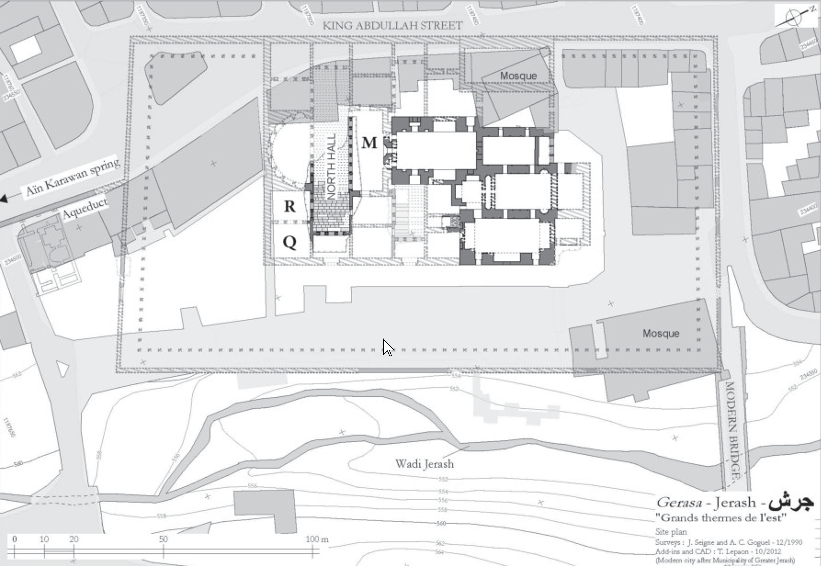

- Fig. 1 Site Map of

East Baths from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1 Site Map of

East Baths from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 7 collapsed

architectural elements in Room A from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 8 Deposition

of large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer in Room M from Lepaon et al. (2018)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Deposition of large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer. It is obvious that the fragments had been smashed and hoarded in Room M, in preparation for recycling; they would have been burnt to produce lime.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Lepaon et al. (2018) - Fig. 9 Deposit of

large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer in Room M from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 10 Deposit of

large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 7 collapsed

architectural elements in Room A from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 8 Deposition

of large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer in Room M from Lepaon et al. (2018)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Deposition of large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer. It is obvious that the fragments had been smashed and hoarded in Room M, in preparation for recycling; they would have been burnt to produce lime.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Lepaon et al. (2018) - Fig. 9 Deposit of

large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer in Room M from Lepaon et al. (2018)

- Fig. 10 Deposit of

large sculptural marble fragments underneath the rubble of the destruction layer from Lepaon et al. (2018)

In 2016, the discovery of a wall constructed with Roman spoils in the northeastern part of Area M (MUR 55004) led to the discovery of a room-shaped dwelling (Fig. 4), which was obviously constructed after the demolition of the ancient monument. All the walls of this dwelling, which were cleared during the 2017 excavation, rested on a 30-50 cm thick soil deposit, which covered the Roman pavement. The remnants of this later structure were completely cleared within the limits of the excavation trenches.

Two walls, orthogonally oriented to the south and the east, formed the southwestern corner of a rectangular chamber measuring approximately 5 m in length and 2.50 m in width, occupying a space of approximately 12.5 m2. This building continues to the north and east, under the unexcavated trench balks; this extension is still totally unknown. The perpendicularly arranged walls of this room consist of numerous Roman period entablature blocks (which are partly delicately decorated), and column drums, which have either smooth (Fig. 5) or spirally fluted shafts. These older architectural elements were reused as building material where they fell, after the collapse of the thermal building due to an earthquake. It should be noted that the interior of the building had been carefully cleared of fallen material, which is only found outside the walls, and scattered arbitrarily. This fact indicates the building postdates the catastrophe, and has nothing to do with any form of recycling of the marble statues, as all of the marble statuary fragments were found underneath collapsed architectural entablature blocks.

The walls of the room were set on a foundation of carefully levelled brownish limestone blocks, which carried, lying horizontally or vertically, column drums and other Roman blocks. The southward face of this masonry, which was discovered in 2016, preserved along its interior base the remains of a layer of sediment and ceramic sherds, which formed the support for a whitish plaster coating. The masonry of the northern face is composed of a column drum, on which quadrangular blocks have been placed. This side of the masonry also displays plaster remains. Such careful plastering of the walls excludes an industrial function, such as a stable for cattle or as an improvised storage for goods.

However, the actual function of this room remains obscure. In light of the discoveries of 2017, the initial hypothesis of a secondary basin cannot be retained. There is no conclusive evidence which would allow a more precise specification of the use of this room. A preliminary study of the pottery indicates that the fragments which were used to support the plaster date to the Byzantine period, while sherds discovered on the floor level belong to the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. After careful documentation, and with the consent of the DoA inspector, this structure was removed by a crane, to allow exploration of the underlying structures. Due to the ancient numbering system on the joint faces of the column drums, it will be possible to attribute these pieces to the corresponding parts of the Roman colonnade in the future, facilitating an anastylosis of the northern hall. The removal of the elements mentioned above was inevitable for this reason also.

A similar level of destruction was revealed throughout the excavation area, apart from the interior of the early Islamic construction described above. As already evidenced by the excavation of 2016, the entire area outside this building was full of tumbled architectural blocks (Fig. 7) such as spirally fluted column shafts, decorated architraves, cornices, and other elements.

The reason for their collapse must have been a natural catastrophe, perhaps an earthquake such as those from the years 551 AD or (more likely) 749 AD. Close investigation of the collapsed building material revealed an accidental deposit distribution of elements according to their size: smaller architectural elements, such as spirally fluted column shafts, or minor column bases destined for naiskoi (niche frames) were predominantly discovered in the upper part of the collapse. In contrast to this, more monumental elements, such as architraves and cornices, were found in the lower part of the rubble. During the extensive excavation of this area, we observed a peculiar scarcity, or even a complete absence of, expected architectural elements which were essential for the realization of both the northern façade cladding of the bathing complex and the southern façade, which formed a sector within the northern portico of the neighboring hall. Apart from one well preserved exception (Fig. 6), no further small Corinthian capitals which would have crowned the spirally fluted column shafts came to light. On the other hand, the excavation made it possible to identify some indurated surfaces (probably walking levels), which reflect an occasional visit to the sector, probably by people who were searching for building material. Selective stone-robbery in the period after the catastrophe could be a plausible explanation for an incomplete inventory of excavated building blocks.

These field observations led to the conclusion that a number of architectural blocks had been recovered for secondary reuse after the violent demolition of the monument, probably caused by the earthquake of 749 AD. As already noted in the previous excavation season, no evidence for the roofing of this compound was discovered. The catastrophe obviously did not cause human casualties, as no trace of human skeletons were uncovered. The isolated animal bones probably should be explained as the remains of food butchery and consumption.

Immediately under the strata connected to the collapse of the architectural structure in Area M, a greyish layer of soil, mixed with ashes and lime, was uncovered over the entire area of excavation. The properties of this stratum testify to the abandonment of Area M prior to the natural catastrophe of 749 AD. Among the archaeological finds from this layer, a coin testifies the abandonment of this area occurred after 642 AD. For this reason, the earthquake of 749 AD was most likely the event which caused the collapse of the Roman period building.

... Almost all statuary fragments came to light in room M under the first destruction layer, which was marked by densely collapsed rubble of massive blocks, mostly from the lavishly decorated entablature which had collapsed during the disastrous earthquake of 749 AD. Even though this catastrophe may have caused further damage to the statues, their deposition in the stratum underneath was, however, a result of previous destructive human activities. People had intentionally accumulated and then smashed sculptures on the rubble above the limestone pavement of room M, obviously to send them for burning, in order to produce lime for domestic construction. This is definitively the reason why major parts of the torsi have not been found, particularly the heads or body extremities. The sugar-like, decayed porous surface of some of the fragments indicates they have been exposed to high temperatures. Even though there is no material evidence for a kiln or furnace, we must take into account that the sculptural fragments are the sad remains of a systematic industrial recycling process. Obviously, the sudden earthquake interrupted this activity and preserved some large parts of marble figures. As a consequence, the find position of a sculpture does not provide any clue for reconstructing its original arrangement within the northern hall. One cannot even exclude the possibility that some of the statues had never decorated either the baths or the northern hall, but had been brought from another area in the urban topography to the designated place for firing10. To our present knowledge, the hoard of marble statuary which has been uncovered was definitely destined for destruction by firing, certainly under the auspices of fundamentalist religious (Christian?) iconoclasts.

10. This hypothesis is corroborated by the fact that the statuary material from the Eastern Great Baths produced until now two statues of Zeus if the identification of the bearded head fragment in Report 2016 ,cat.-no. 1 is correct.

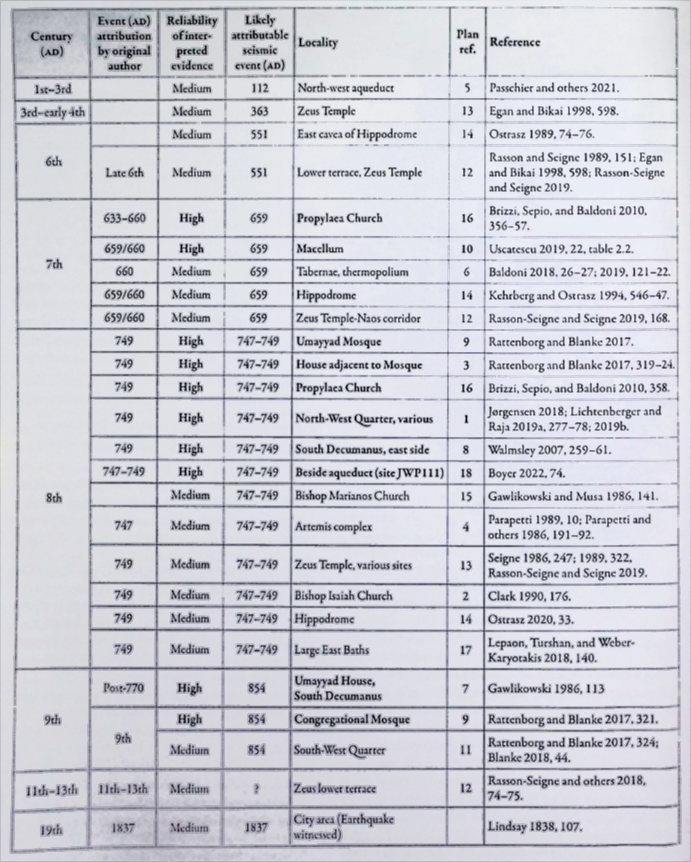

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Large East Baths | 17 | Lepaon, Turshan, and Weber-Karyotakis 2018. |

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Area M |

Fig. 7 |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Seismic Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Area M |

Fig. 7 |

|

|

Lepaon, T., Turshan, N., & Weber-Karyotakis, T. M. (2018). The ‘Great Eastern Baths’ of Jerash/Gerasa: Balance of knowledge and ongoing research

. In A. Lichtenberger & R. Raja (Eds.), The Archaeology and History of Jerash: 110 Years of Excavations, Jerash Papers, 1 (pp. 131-142). Turnhout: Brepols.

Lepaon, T. & Weber-Karyotakis, T. M. (2018) The Great Eastern Baths At Gerasa / Jarash Report On The Excavation Campaign 2017

, ADAJ 59, 477-502

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

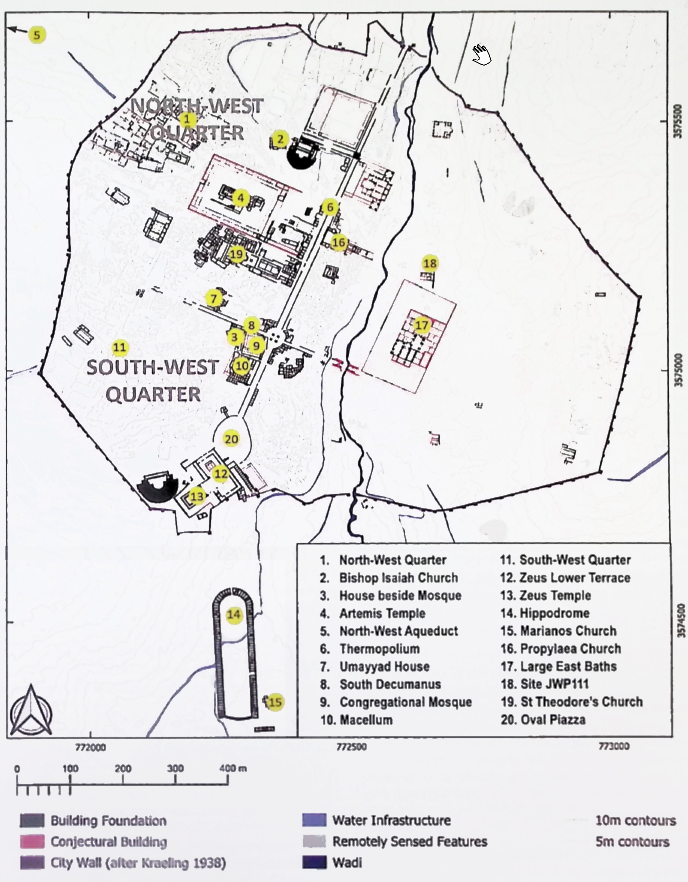

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)