Herodium

Aerial View of Herodium

Aerial View of HerodiumClick on Image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Asaf T. - Wikipedia - Public Domain

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Herodium | Latin | |

| Herodeion | Greek | Ἡρώδειον |

| Herodium | Hebrew | הרודיון |

| Har Hordus | Hebrew | |

| Herodis | Hebrew | הרודיון |

| Herodium | Name in documents from the time of Bar-Kokhba | |

| Jabal al-Fureidis | Arabic | جبل فريديس |

| Herodion | alternate spelling | |

| Frank Mountain | ||

| Mountain of Little Paradise | ||

| Bethulia |

Herodium is located about 5 km. SE of Bethlehem and was described in detail by

Josephus. The fortress on the site was constructed by

King Herod - likely between 24 and 15 BCE

(Gideon Foerster in Stern et al, 1993).

Herodium lies about 12 km (7.5 mi.) south of Jerusalem as the crow flies (map reference 1731.1192). The fortress of Herodium is situated on a hill 758 m above sea level. Its position and appearance accord with the evidence provided by Josephus, who locates the fortress 60 stadia from Jerusalem and describes the hill, which is in the form of a truncated cone, as being shaped like a woman's breast (Antiq. XV, 324). The Arabic name of the hill, Jebel Fureidis, evidently preserves the name Herodis, as it was called in documents from the time of Bar-Kokhba. Excavations at the site have confirmed the identification of Jebel Fureidis with Herodium.

The main literary source for the history of Herodium are the writings of Josephus. The fortress is also mentioned by Pliny (NHV, 70) and in several documents from the time of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt. Herodium was built on the spot where Herod, when retreating from Jerusalem to Masada in flight from Matathias Antigonus and the Parthians in 40 BCE, achieved one of his most important victories over the Hasmoneans and their supporters (Antiq. XIV, 359-360; War I, 265).

Herodium appears to have been built after Herod's marriage to Mariamne, the daughter of Simeon the Priest of the House of Boethus. It was probably not constructed before 24 BCE, but it was prior to Marcus Agrippa's visit to Judea, which included Herodium, in 15 BCE (Antiq. XV, 323; XVI, 12-13). According to Josephus, Herodium was built to serve as a fortress and the capital of a toparchy, as well as a memorial to Herod (Antiq. XV, 324; War I, 419; III, 55). Josephus also gives a full description of Herod's funeral procession to his burial place at Herodium (War I, 670-673; Antiq. XVII, 196-199). During the First Jewish Revolt, Herodium was the scene of some of the internal strife among the Zealots (War IV, 518-520). It is listed together with Masada and Machaerus as one of the last three strongholds, in addition to Jerusalem, remaining in the hands of the rebels on the eve of the siege of Jerusalem (War IV, 555). Herodium was the first of these strongholds to be captured by the Romans after Jerusalem fell (War VII, 163). According to documents found at Wadi Murabba'at from the time of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt, Simeon, Prince of Israel (Bar-Kokhba), had a command post at Herodis, where, among other things, land transactions were carried out and a treasury was kept - perhaps storehouses of grain.

In the fifteenth century, the Italian traveler F. Fabri gave the name Mountain of the Franks to Herodium, the place where, he assumed, the Crusaders made a stand after the Arab conquest of Jerusalem (P PTS X, 403). It retained this name until the nineteenth century. The first sketch of Herodium's plan was made by E. Pococke during a visit in 1743. E. Robinson, in 1838, gave a detailed description of its buildings, dating them to the Roman period and noting their resemblance to Josephus' description. In 1863, the French explorer and traveler F. de Saulcy recorded important site details and drew sketches and plans of the buildings at the foot of the hill, especially of the pool. In his opinion, the round structure in the pool was Herod's burial place. Several years later, V. Guerin accurately described the outer wall with its three semicircular towers and eastern round tower. Until the modern excavations, the fullest account of the remains was made in 1879 by C. Schick, with plans and cross sections. He noted that the lower part of Herodium was a natural hill and the upper part was artificial. Schick traced the staircase leading to the structure on the summit of the hill; his assumption that the steps led to the courtyard of the building through a tunnel-like passage dug in the artificial fill was later confirmed. His further assumption that cisterns had been dug in the lower part of the hill was also later verified. In addition, Schick was correct in his belief that the upper structure had been designed as a grandiose mausoleum and not merely a stronghold. In 1881, C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener prepared the first accurate plan of the site with the two circular walls, three semicircular towers, and a round eastern tower.

From 1962 to 1967, V. Corbo conducted four seasons of excavations at the site on behalf of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum. At that time, most of the main buildings on the summit from the Herodian period, the period of the two wars with Rome, and the Byzantine period were uncovered.

Preservation and restoration works were carried out in 1967 and 1970 by G. Foerster for the National Parks Authority. The entrance room to the palace was uncovered, as well as a complex network of cisterns and an elaborate system of tunnels dug in the hill that apparently dated to the time of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt.

Excavations were resumed in 1970 by an expedition headed by E. Netzer, on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (see below).

The investigations at Herodium have, to a great extent, confirmed Josephus' detailed description of the place in the Herodian period (Antiq. XV, 324-325): "This fortress, which is some sixty stades distant from Jerusalem, is naturally strong and very suitable for such a structure, for reasonably nearby is a hill, raised to a (greater) height by the hand of man and rounded off in the shape of a breast. At intervals it has round towers, and it has a steep ascent formed of two hundred steps of hewn stone. Within it are costly royal apartments made for security and for ornament at the same time. At the base of the hill there are pleasure grounds built in such a way as to be worth seeing, among other things because of the way in which water, which is lacking in that place, is brought in from a distance and at great expense. The surrounding plain was built up as a city second to none, with the hill serving as an acropolis for the other dwellings."

Three more excavation seasons were conducted at Lower Herodium between 1997 and 2000, by an expedition of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem under the direction of E. Netzer, with the assistance of Y. Kalman and R. Laureys-Chachy. The work concentrated in two areas: southwest of the pool complex; and in the vicinity of the monumental building at the western end of the “artificial course,” an elongated man-made platform north of the remains of the large palace.

- Annotated Aerial View of Herodium

from biblewalks.com

Annotated Aerial View of Herodium

Annotated Aerial View of Herodium

Google and biblewalks.com - Herodium in Google Earth

- Herodium on govmap.gov.il

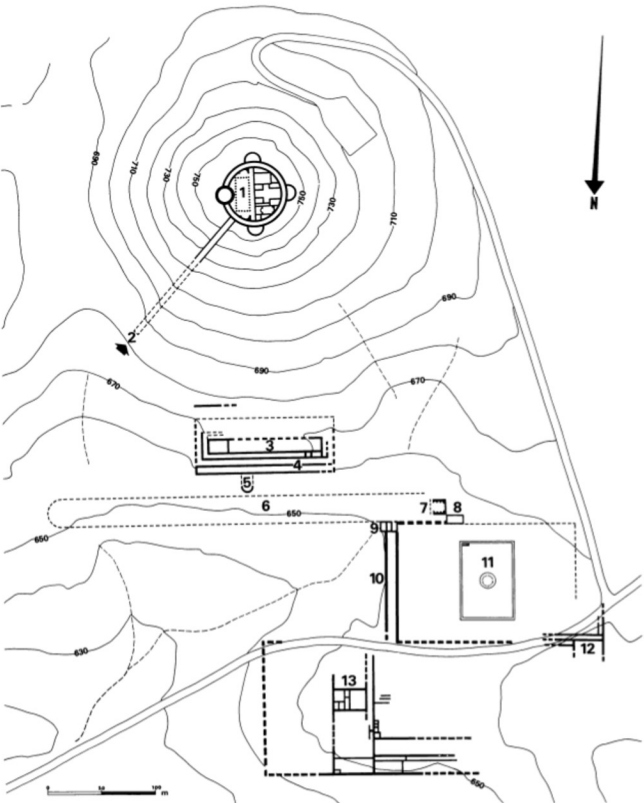

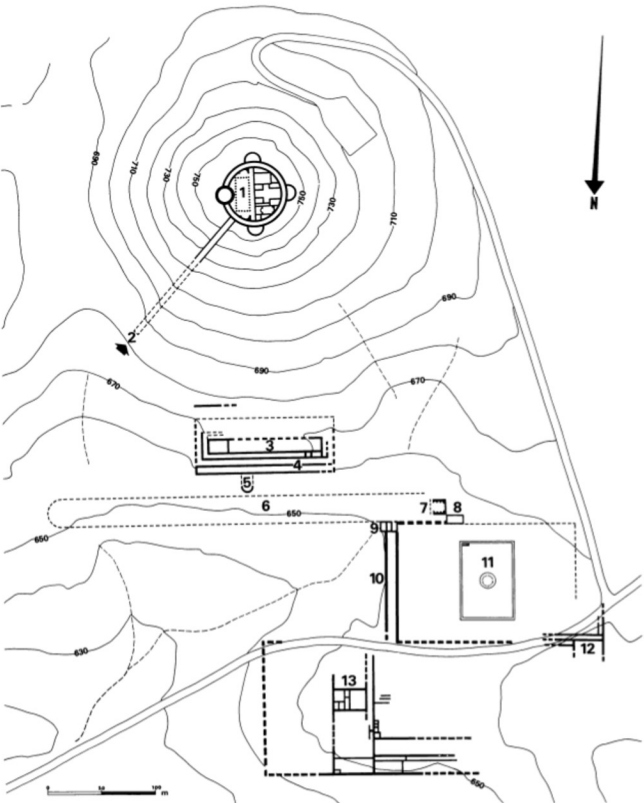

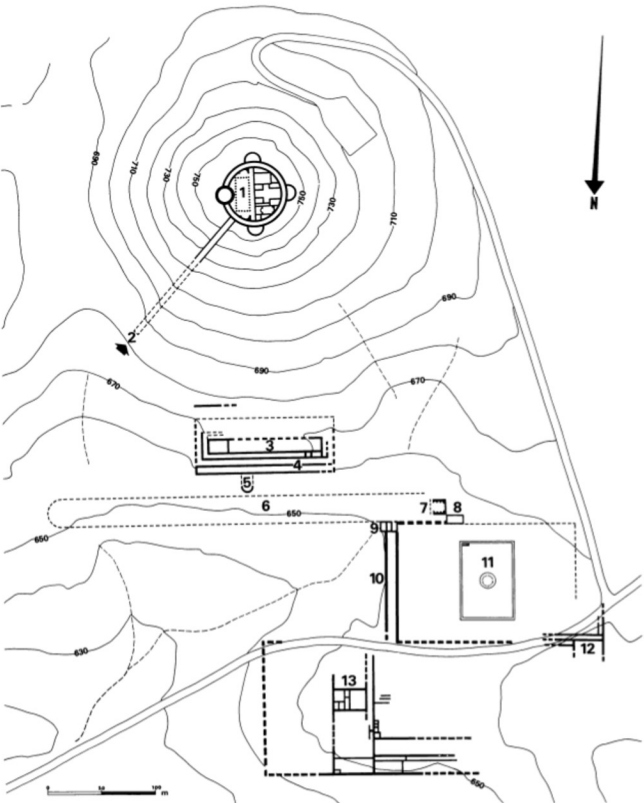

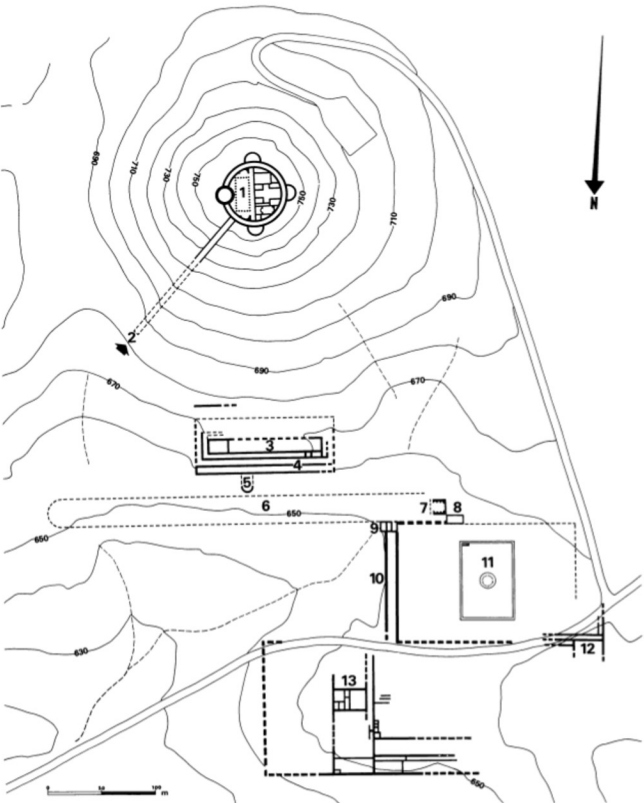

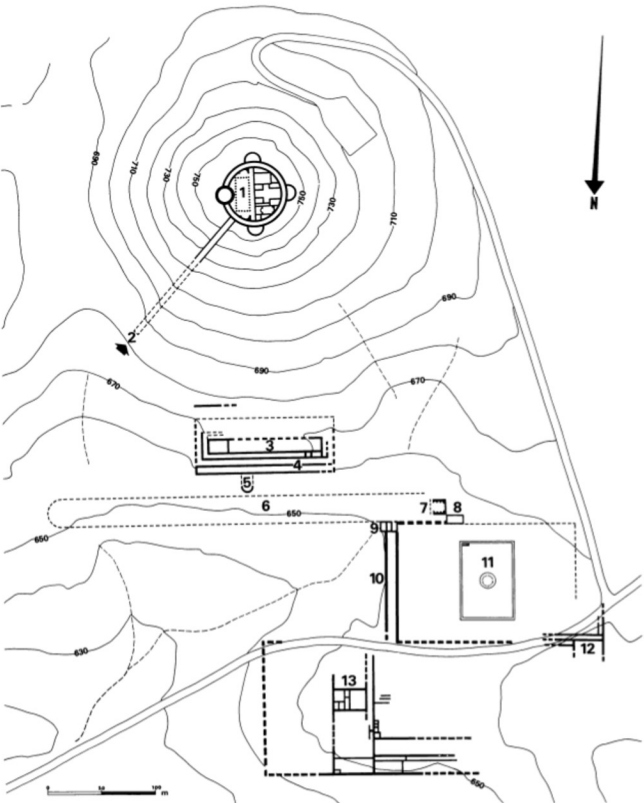

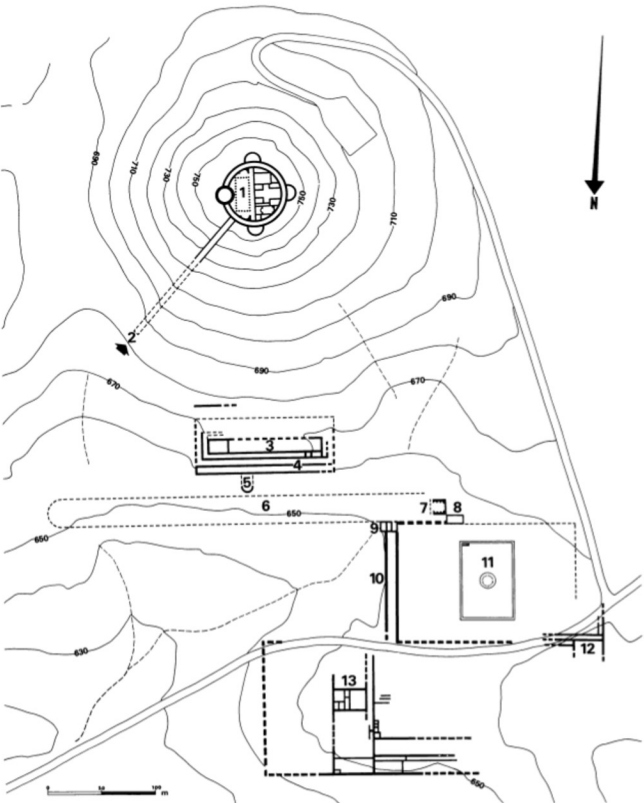

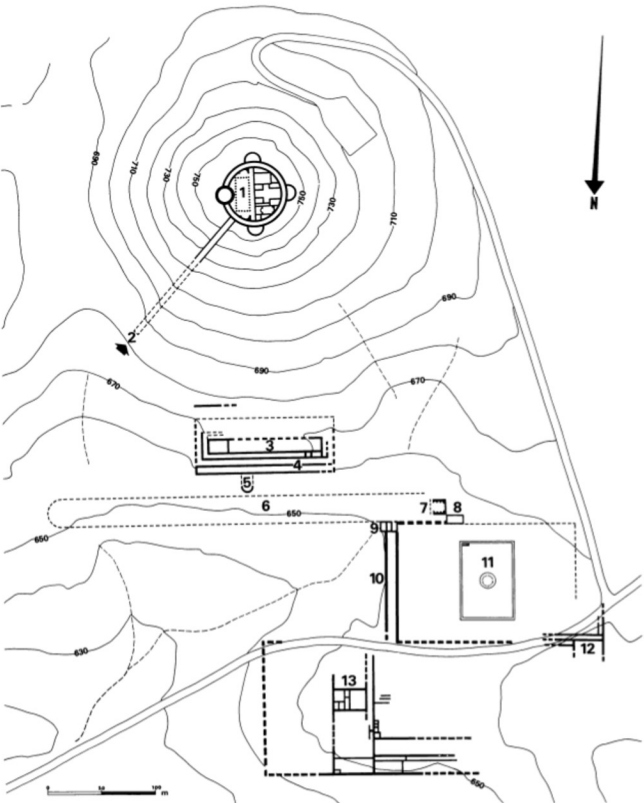

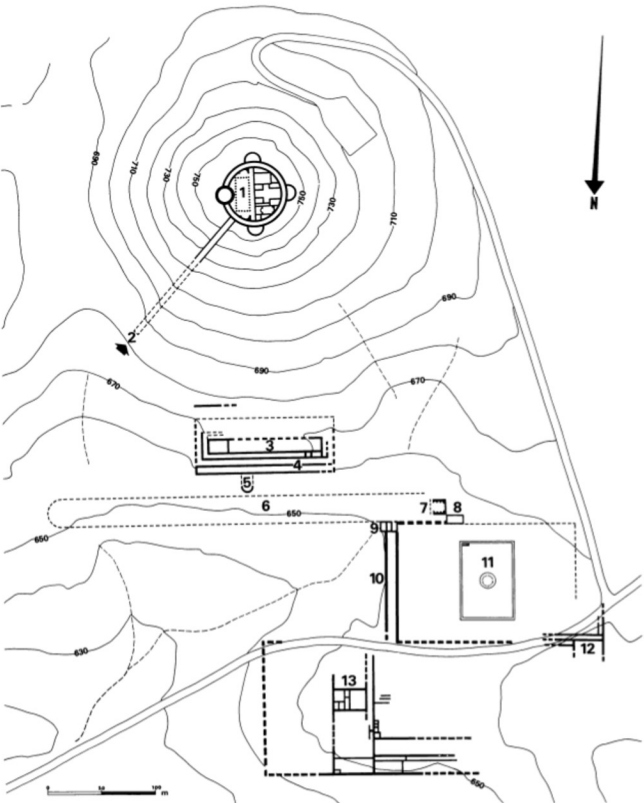

- from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 85

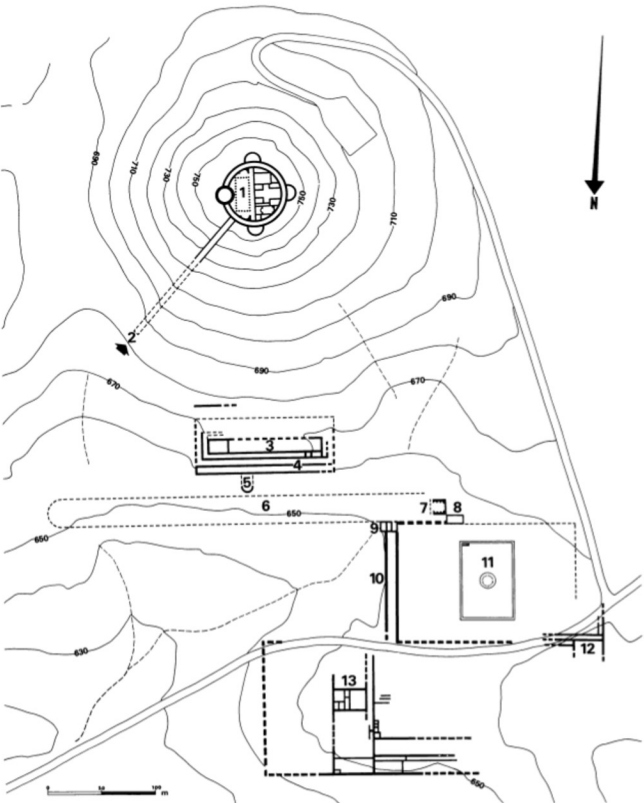

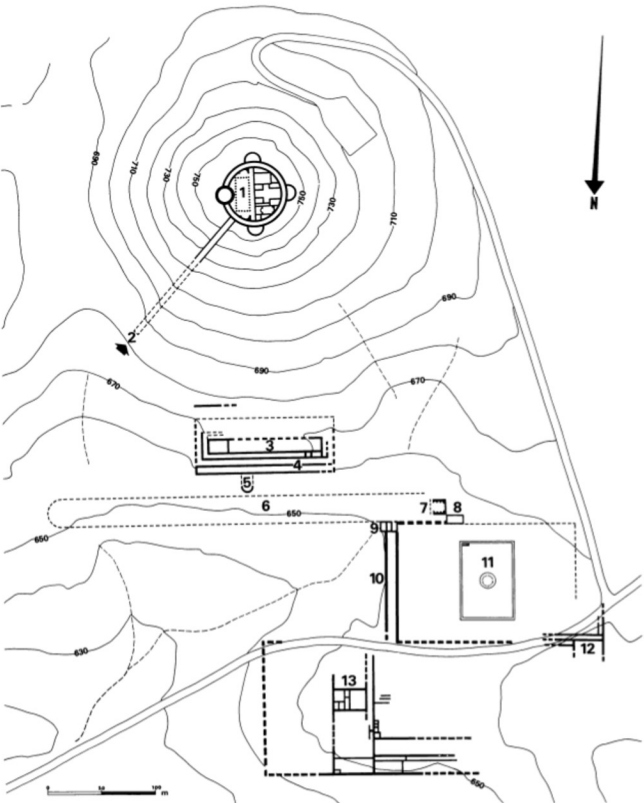

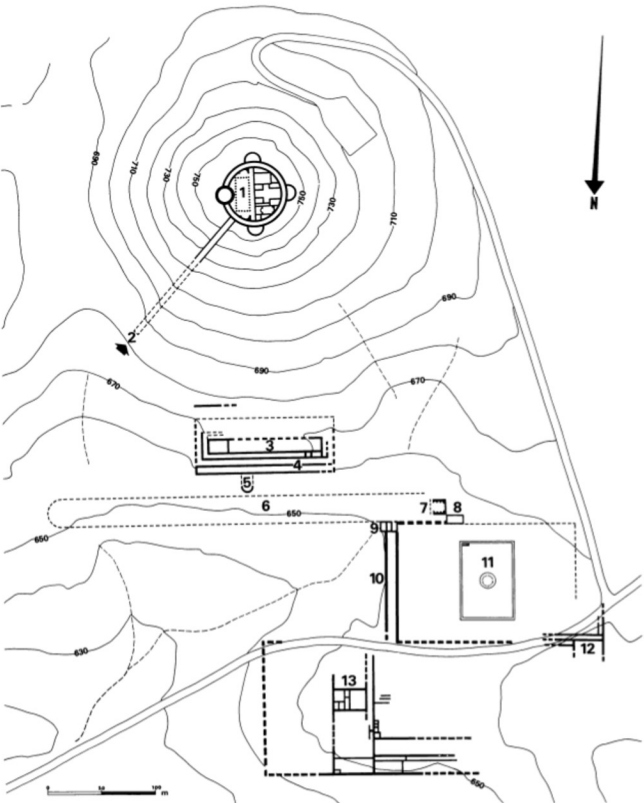

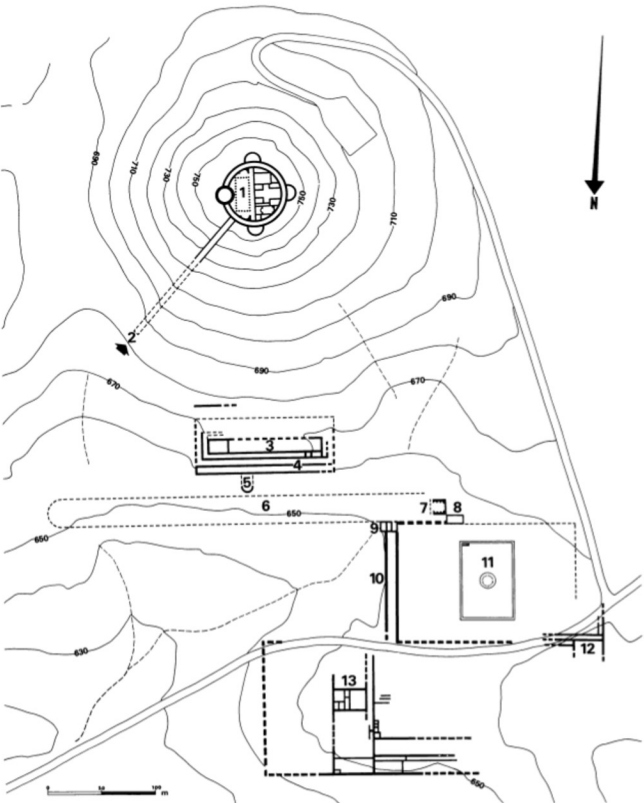

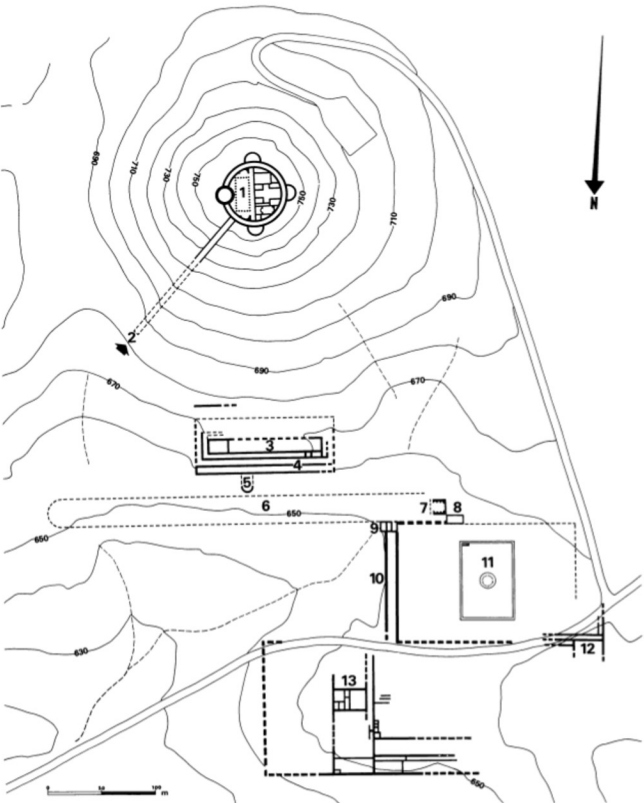

Ill. 85General plan of Greater Herodium:

- The mountain palace-fortress

- The main stairway to the mountain

- The large palace (building A101)

- The large palace's substructural halls

- A tentative balcony adjacent to the large palace

- The course

- The monumental building

- Building B14

- A rectangular structure—the south-eastern corner of the pool complex

- A damlike wall with galleries on top

- The pool complex, with the pool in its center

- The service building

- The northern wing

Netzer (2008)

- Ill. 85 General plan of

greater Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 85

Ill. 85

General plan of Greater Herodium:

- The mountain palace-fortress

- The main stairway to the mountain

- The large palace (building A101)

- The large palace's substructural halls

- A tentative balcony adjacent to the large palace

- The course

- The monumental building

- Building B14

- A rectangular structure—the south-eastern corner of the pool complex

- A damlike wall with galleries on top

- The pool complex, with the pool in its center

- The service building

- The northern wing

Netzer (2008) - General plan of the site

from Stern et al (1993)

Herodium: general plan of the site.

Herodium: general plan of the site.

Stern et al (1993)

- Ill. 85 General plan of

greater Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 85

Ill. 85

General plan of Greater Herodium:

- The mountain palace-fortress

- The main stairway to the mountain

- The large palace (building A101)

- The large palace's substructural halls

- A tentative balcony adjacent to the large palace

- The course

- The monumental building

- Building B14

- A rectangular structure—the south-eastern corner of the pool complex

- A damlike wall with galleries on top

- The pool complex, with the pool in its center

- The service building

- The northern wing

Netzer (2008) - General plan of the site

from Stern et al (1993)

Herodium: general plan of the site.

Herodium: general plan of the site.

Stern et al (1993)

- Ill. 9 General plan of

the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 9

Ill. 9

General plan of the pool complex

Netzer (2008)

- Ill. 9 General plan of

the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 9

Ill. 9

General plan of the pool complex

Netzer (2008)

- Ill. 36 Plan of the

service building in the the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 36

Ill. 36

Plan of the service building

Netzer (2008)

- Ill. 36 Plan of the

service building in the the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 36

Ill. 36

Plan of the service building

Netzer (2008)

- Reconstruction of the site

around 15 BCE from Langgut (2022)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Reconstruction of the mausoleum garden during its early period, around 15 BCE

drawing by Y. Korman

Langgut (2022)

- Reconstruction of the site

around 15 BCE from Langgut (2022)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Reconstruction of the mausoleum garden during its early period, around 15 BCE

drawing by Y. Korman

Langgut (2022)

- Ill. 8 General view of

the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 8

Ill. 8

General view of the pool complex (at end of 1972 season).

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 28 Door sill and

fallen jamb in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 28

Ill. 28

Door sill and fallen jamb east of wall W159 (in sounding B11), looking east

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 37 Storage hall, B20,

showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 37

Ill. 37

Storage hall, B20, showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling, looking north-west. In the background can be seen the later wall (W101).

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 38 Rooms B56, B57, and

B20 in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 38

Ill. 38

Rooms B56, B57, and B20 (in the background), looking east. A section of room B55 can be seen in the foreground.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 39 restored storage

jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 39

Ill. 39

Group of restored storage jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 42 Hall B41 with debris

from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 42

Ill. 42

Hall B41, facing south, with wall W34 on the right, in an carly stage of the excavations (1972). Note the heavy debris of building stones.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 43 collapsed arches

of hall B41 in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 43

Ill. 43

Two collapsed arches fallen from wall W35 (of hall B41). looking east.

Netzer (2008)

- Ill. 8 General view of

the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 8

Ill. 8

General view of the pool complex (at end of 1972 season).

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 28 Door sill and

fallen jamb in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 28

Ill. 28

Door sill and fallen jamb east of wall W159 (in sounding B11), looking east

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 37 Storage hall, B20,

showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 37

Ill. 37

Storage hall, B20, showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling, looking north-west. In the background can be seen the later wall (W101).

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 38 Rooms B56, B57, and

B20 in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 38

Ill. 38

Rooms B56, B57, and B20 (in the background), looking east. A section of room B55 can be seen in the foreground.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 39 restored storage

jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 39

Ill. 39

Group of restored storage jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 42 Hall B41 with debris

from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 42

Ill. 42

Hall B41, facing south, with wall W34 on the right, in an carly stage of the excavations (1972). Note the heavy debris of building stones.

Netzer (2008) - Ill. 43 collapsed arches

of hall B41 in the pool complex of lower Herodium from Netzer (2008)

Ill. 43

Ill. 43

Two collapsed arches fallen from wall W35 (of hall B41). looking east.

Netzer (2008)

- from Netzer (1981:10)

- The pool complex including the service building (B20).

- The large palace (A101).

- The course including the adjacent monumental building (B28) and building B14.

- The northern wing.

- The boundaries, roads, and water system.

- from Netzer (1981:22-24)

The hall was originally covered by a barrel-vaulted ceiling, which probably supported a second storey. The floor level of the long hall was 2.2 m. lower than the original terrain on its north side. We assume that the lower floor was cut into the original terrain, so that the conjectured upper floor would fit the floor levels or the ground floor on the north. At a later stage, perhaps close to the middle of the first century A.D., the barrel-vaulted ceiling collapsed (III. 37), the hall was soon restored, and at this stage it was divided into three rooms (Ills. 36, 38).

Dozens of storage jars that were smashed by the stones of the barrel-vaulted ceiling when it collapsed were found on the original floor of the hall. The jars are almost all of the same type known as the bellshaped jar (IIl. 39 and Pl. 2). The stones that had shattered the jars (and several other vessels) were found more or less in rows directly on the floor, which indicates that an earthquake was probably the cause of their collapse.

The floor of the original hall was coated with the typical gray hydraulic plaster which was also preserved to a height of 40 cm. on the walls. We can therefore assume that this hall was built especially as a storage room for liquids.12 This assumption was strengthened by the discovery of quasi-pythos bases which were sunk into the floor, 4 m apart, along the northern wall (Ills. 36, 40). These hollows probably caught the liquid which spilled out of broken jars and stored them for reuse.13

After the destruction of the long hall and its rebuilding and subdivision, wall W101, which separated rooms B20 and B57, was built above the broken storage jars and the fallen ceiling stones. The new beaten-earth floor laid on top of the fallen ceiling was very loose and difficult to define, but its level is indicated by the door inserted into the abovementioned late wall, W101 (IIl. 37).14 No storage jars were found beneath the two rooms of the later phase, B57 (3.3 m. long) and B56 (5.1 m. long), at least in those sections in which we reached the original floor. Either no jars were originally stored here, or, they were removed during construction. As in hall B20, it was difficult to determine the exact level of the later floors in the later rooms, B56 and B57.

A water channel, probably belonging to the original building, was exposed at the far end of the storage hall. This channel, about 20 cm. wide, was about 1.4 m. higher than the floor level of the original hall, most likely because the long hall was lower than its surroundings. Part of the channel was built above stone consoles which projected from wall W30 (Ills. 36, 41), a technique which is so far unknown in Herodian buildings. Its continuation, along wall W99, ran above a low wall and continued into the courtyard (see below).

Many broken vessels were found between the fallen stones of the thick mass of debris (2 m. at some points) that covered these rooms and part of the adjacent courtyard. The vessels, some of which were complete, probably came from an upper floor or adjacent rooms located on the higher terrain to the north.

11. Some of the ashlar courses here are composed mostly of headers.

12. This function may have also been the reason for the construction here

of a barrel-vaulted ceiling (this subject will be discussed in chapter V).

13. A chemical analysis of the salts found on many of the jar fragments,

carried out in the chemistry laboratory of the Institute of Archaeology,

Tel Aviv University, unfortunately gave no clear indication of the type of stored liquid.

14. It seems that when this hall was rebuilt (or later) the original floor

was reached along the northern wall (W30) in a strip about 60 cm. wide.

No ceiling stones were found here, and the various vessels uncovered differed

from the jars which lay on the rest of the hall's floor.

- from Netzer (1981:24-26)

Hall B41 and room B55 were originally a single unit. At the time of their construction, or later, they were divided by a thin partition wall (W102) only 50 cm. wide. Hall B41 was paved with a flat fieldstone floor while room B55 had a beaten-earth floor.

Since the stone-paved floor of hall B41 was 70-75 cm. lower than the sills of the openings in the eastern wall, they were probably not entrances, but may have been mangers for horses or mules. We can therefore assume that hall B41 was originally a stable similar to those found at Memphis (Kurnub)15 and other sites. Room B55, which had no door at floor level, may have been used for storing the hay or fodder. It probably had an entrance high up in the partition wall to keep the animals out of the room. The close proximity of this room to the courtyard and its water installations also indicates that it may have served as a stable.

The basic difference in building techniques among the storage hall, hall B41, and room B55 should be noted. Whereas the walls on both sides of the storage hall were built of ashlars (on both faces), the walls surrounding rooms B41 and B55 were built of courses of fieldstones of moderate size, levelled with small stones. This difference in building technique is most evident in the northern wall (W30) which connected the storage hall with room B55 (III. 41). Room B20 was probably designed from the outset to serve as a storage room for liquids, and its construction was therefore of higher standard than hall B41 and room B55, which were used as a stable.

After their destruction by an earthquake, hall B41 and room B55 together became a rubbish dump. An accumulation of small stones and sherds lay in a heap, about 3.5 m. long, on the floor in the northern part of B41. Room B55 was also full of rubbish, including numerous sherds.16

15. A. Negev: Kurnub, EAEHL (1977), III, pp. 724, 727.

16. It seems that in room B55 there was a slow process of accumulation on the

original floor (at +659.67) before it was turned into a rubbish pit (at about +660.40).

- from Netzer (1981:26)

At a later stage, probably after the destruction of the halls, the eastern part of the courtyard, a strip about 2.5 m. wide, was separated from the rest of the courtyard by means of a thin wall (Ill. 28). This wall covered one of the water channels which were probably no longer in use and bounded the area which now served only as a rubbish dump. A benchshaped structure attached to wall W29 east of the small pool can also, probably, be dated to this later stage. A column base in secondary use was incorроrated into the bench-shaped structure.

- from Netzer (1981:26-27)

Hall B52 was originally a long room, at least 8 m. long and 3.4 m. wide. Its walls, of which only small sections were exposed, and ceiling were coated with a white lime plaster, many fragments of which had fallen on the beaten-earth floor. The plaster fragments were smooth on one side, and on the other side they bore the negative imprints of cane bundles, a technique familiar from other Herodian sites (IlI. 46). It can therefore be assumed that this hall was already destroyed when the water channel and the pool in Loci B40 and B58 were built, perhaps at the time when the changes took place in the storage hall, etc., but possibly also earlier.

North of hall B52, at a level 3 m. higher, part of a cobblestone floor which probably belonged to courtyard B51 was exposed (III. 36). The courtyard and the hall were bounded on the west by wall W33, of which only fragments have survived. Above these remains was built a Byzantine building. Only part of its white mosaic floor and a section of a wall to its south were cleared. In a fill below this floor were found many fragments of colored Herodian plaster which probably came from nearby palatial rooms (III. 36, section).

In an attempt to locate a continuation of the water channel in Loci B40 and B58, we made a sounding (B59) north of room B55 and adjacent to wall W34 (IIl. 36). Under a rubbish dump, about 1.0 m. thick, we reached a floor containing a round oven. Unfortunately we were forced to cease work at this point.

17. The entire area (Loci B52, B58, B51) was severely damaged by a bulldozer between the seasons of 1972 and 1973. We therefore enlarged the excavated area.

- from Netzer (1981:27-28)

The history of the service wing exhibits at least three stages of building:

- The original Herodian stage.

- A stage of reconstruction, probably in the wake of large-scale destruction possibly caused by an earthquake. Such a conclusion must be viewed with caution, as there is no definite evidence of such an earthquake from the other parts of the site.20 If indeed there was an earthquake, it should probably be dated to the year 48 A.D.21 Coins of Agrippa I and others found on the floors of the reconstructed building (and in the dumps), however, point to a date towards the middle of the first century A.D.22

- The Byzantine period, during which buildings of the Herodian period already lay in ruins.

18. In both cases, but especially in the latter case, this service building

could have been an integral part of the northern wing (see below).

19. So far, no survey has located the ancient road from Jerusalem to Herodium.

20. See Corbo (1963), p. 228.

21. D.H. Kellner-Amiran: A Revised Earthquake Catalogue of Palestine, IEJ, 1 (1950–51), p. 225.

22. Theoretically, the earthquake can also be dated to A.D. 30 or 33 according to the

above-mentioned catalogue, but most of the coins uncovered here indicate the

earthquake of A.D. 48.

- from Netzer (1981:78)

It is likely that the construction of Herodium took place between the years 23 B.C., the date of Herod's marriage to the daughter of Simon, the High Priest, and 15 B.C., when Marcus Agrippa visited Judea (and see above, n. 1 in Chapter I). This date can be verified by the artifacts discovered at the site: the pottery, glass, coins, etc. Unfortunately, the pottery from the mountain palace-fortress, which also could serve as evidence for the date of its establishment, has not yet been published.

No historical data is available concerning the fate of Herodium during the period following Herod's death until the First Revolt against the Romans. The good condition of the mountain palace-fortress at the time of the revolt bears witness that the building was well cared for from Herod's days up to this time, almost ninety years later. It seems that Herodium continued to serve as a palace and fortress during the rule of Herod's son, Archelaus (4 B.C. - A.D. 6) and the Roman procurators, including the three years during which Agrippa I ruled the country (A.D. 41-44). On the other hand, the possibility еxists that during this period (from Herod's death until the mid-first century A.D., or even until the First Revolt) occupation at the site was not as intensive as it may have been during either Herod's lifetime or the final years before the destruction of the site in A.D. 70.

Because of the poor state of preservation of the buildings in Lower Herodium as compared with the upper fortress, and the fact that many of them were reoccupied during Byzantine times, and that the area was only partially excavated, it cannot be determined if Lower Herodium was also well maintained. The excavations in the service building indicate some deterioration; however, this was probably due to an earthquake which occurred in the mid-first century A.D. We do not know whether or not the other parts of the lower site suffered a similar fate.

No evidence was uncovered to indicate if Lower Herodium was still inhabited at the time of the Second Revolt against the Romans, although future excavations may reveal that parts of the area were still in use at that time.

We do not know the exact date of the resettlement of the site in the Byzantine period, but the ceramic evidence indicates that the main period of occupation was during the fifth and sixth centuries A.D. and continued into the Early Muslim period. The publication of the church which was cleared in the area of the northern wing, and the results of the 1980 season, will add further information and allow for a more detailed study of the Byzantine period.

Only small areas of Lower Herodium have been exposed to date, but the accumulated evidence, both architectural and ceramic, provides an excellent preliminary picture of the character and development of the lower regions of this extensive site.

11. Some of the ashlar courses here are composed mostly of headers.

12. This function may have also been the reason for the construction here

of a barrel-vaulted ceiling (this subject will be discussed in chapter V).

13. A chemical analysis of the salts found on many of the jar fragments,

carried out in the chemistry laboratory of the Institute of Archaeology,

Tel Aviv University, unfortunately gave no clear indication of the type of stored liquid.

14. It seems that when this hall was rebuilt (or later) the original floor

was reached along the northern wall (W30) in a strip about 60 cm. wide.

No ceiling stones were found here, and the various vessels uncovered differed

from the jars which lay on the rest of the hall's floor.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

The storage hall in Lower Herodium

Ill. 85

Ill. 85General plan of Greater Herodium:

Netzer (2008)

General plan of the pool complex

General plan of the pool complexNetzer (2008) |

Ill. 37

Ill. 37Storage hall, B20, showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling, looking north-west. In the background can be seen the later wall (W101). Netzer (2008)

Ill. 39

Ill. 39Group of restored storage jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall. Netzer (2008) |

|

|

Hall B41 in Lower Herodium

Ill. 85

Ill. 85General plan of Greater Herodium:

Netzer (2008)

General plan of the pool complex

General plan of the pool complexNetzer (2008) |

Ill. 43

Ill. 43Two collapsed arches fallen from wall W35 (of hall B41). looking east. Netzer (2008)

Ill. 42

Ill. 42Hall B41, facing south, with wall W34 on the right, in an carly stage of the excavations (1972). Note the heavy debris of building stones. Netzer (2008) |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The storage hall in Lower Herodium

Ill. 85

Ill. 85General plan of Greater Herodium:

Netzer (2008)

General plan of the pool complex

General plan of the pool complexNetzer (2008) |

Ill. 37

Ill. 37Storage hall, B20, showing its collapsed barrel-vaulted ceiling, looking north-west. In the background can be seen the later wall (W101). Netzer (2008)

Ill. 39

Ill. 39Group of restored storage jars which were found on the floor of the early storage hall. Netzer (2008) |

|

|

|

Hall B41 in Lower Herodium

Ill. 85

Ill. 85General plan of Greater Herodium:

Netzer (2008)

General plan of the pool complex

General plan of the pool complexNetzer (2008) |

Ill. 43

Ill. 43Two collapsed arches fallen from wall W35 (of hall B41). looking east. Netzer (2008)

Ill. 42

Ill. 42Hall B41, facing south, with wall W34 on the right, in an carly stage of the excavations (1972). Note the heavy debris of building stones. Netzer (2008) |

|

|

E. Netzer, Greater Herodium (Qedem 13), Jerusalem 1981.

E. Netzer, IEJ22 (1972), 247-249

id., RB 80 (1973), 419-421

id., MdB !7 (1981), 17-21;

id., BAR 9/3 (1983), 30-51

14/4 (1988), 18-33

id., ESI5 (1986), 49-50

id., Christian Archaeology in the

Holy Land (V. C. Corbo Fest.), Jerusalem 1990, 165-176

A. Rabinovitch, MdB 9 (1979), 51-53;

C.Patrick, SRI Journal3j6 (1983), 2-3

D. Milson, LA 39 (1989), 207-211

L. Di Segni, V. C. Corbo Fest.

(op. cit.), Jerusalem 1990, 177-190.

S. Loffreda, La Ceramica di Macheronte e dell’Herodion: (90 a.C. –135 d.C.) (SBF Collectio Maior 39), Jerusalem 1996.

T. Braxmeier & P. Beckmann, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 2 (1990), 79–82

M. T. Shoemaker, BAR 17/4 (1991), 58–60

A. Strobel,

Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 2 (1990),

73–78

3 (1991), 82–84

6 (1999), 109–115

J. Michel, Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome, Antiquite

103 (1992), 735–783

E. Netzer, ABD, 3, New York 1992, 176–180

id., Ancient Churches Revealed (ed.

Y. Tsafrir), Jerusalem 1993, 219–232

id., Judaea and the Greco-Roman World in the Time of Herod in the

Light of Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 27–54

id., Die Paläste der Hasmonäer und Herodes’

des Grossen (Antike Welt Sonderhefte

Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie), Mainz am Rhein 1999

id.,

Roman Baths and Bathing, 1: Bathing and Society (JRA Suppl. Series 37), Portsmouth, RI 1999, 45–55

id.,

One Land—Many Cultures, Jerusalem 2003, 277–285

id., The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder,

Tübingen (forthcoming)

J. Patrich, IEJ 42 (1992), 241–245 (Review)

G. Foerster, BA 56 (1993), 143–144;

D. Amit, Cathedra 71 (1994), 198

id., LA 44 (1994), 561–578

id., The Aqueducts of Israel, Portsmouth,

RI 2002, 253–266

H. Eshel, JSRS 4 (1994), 108–109, 112

J. Magness, Revue de Qumran 16/63 (1994),

397–419

id. (& E. E. Cook), BAR 22/6 (1996), 37–52

id., OEANE, 3, New York 1997, 18–19

I. Nielsen,

Hellenistic Palaces: Tradition and Renewal (Studies in Hellenistic Civilization 5), Aarhus 1994

id., Roman

Baths and Bathing, 1: Bathing and Society (op. cit.), Portsmouth, RI 1999, 35–43

A. Ovadiah, 5th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, Bath, 5–12.9.1987 (JRA Suppl. Series 9

eds. P. Johnson et al.), Ann

Arbor, MI 1994, 67–77

K. Fittschen, Judaea and the Greco-Roman World in the Time of Herod in the Light

of Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 139–161

R. Förtsch, ibid., 73–119

P. Richardson, Herod:

King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans (Studies on Personalities of the New Testament), Columbia, SC

1996

id., Building Jewish in the Roman East (Suppls. to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 92), Waco,

TX 2004, 253–269

A. Schmidt-Colinet, Basileia: Die Paläste der hellenistischen Könige. Internationales

Symposium, Berlin, 16–20.12.1992 (Schriften des Seminars für klassische Archäologie der Freien Universität, Berlin

eds. W. Höpfner & G. Brands), Mainz am Rhein 1996, 250–251

Le opere fortificate de Erode

il Grand, Firenze 1997

S. Verhelst, RB 104 (1997), 223–236

D. W. Roller, The Building Program of Herod

the Great, Berkeley, CA 1998

A. Speransky-Marshak, IEJ 48 (1998), 190–193

D. M. Jacobson, BAIAS 17

(1999), 67–76

id., PEQ 134 (2002), 84–91

A. Lichtenberger, Die Baupolitik Herodes des Grossen (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 26), Wiesbaden 1999

S. Santelli et al., Les Dossiers d’Archéologie

240 (1999), 78–80

E. M. Laperrousaz, Trois hauts lieux de Judee, Paris 2001

A. Mazar, The Aqueducts of

Israel, Portsmouth, RI 2002, 211–244

G. D. Stiebel, One Land—Many Cultures, Jerusalem 2003, 215–244;

L. B. Kavlie, NEAS Bulletin 49 (2004), 5–14

L. I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand

Years, 2nd ed., New Haven, CT 2005, 63

A. Lewin, The Archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine, Los

Angeles, CA 2005, 116–119.

E. Netzer (et al.), JSRS 9 (2000), xv–xvi

10 (2001), xviii–xix

id., BAIAS 19–20 (2001–

2002), 186–187

J. Magness, Hesed ve-Emet (E. S. Frerichs Fest.

eds. J. Magness & S. Gitin), Atlanta, GA

1998, 313–329

id., BASOR 322 (2001), 43–46

Y. Kalman, JSRS 10 (2001), xix–xx

S. Bonato-Baccari,

Latomus 61 (2002), 67–87

N. Kokkinos, BAR 28/2 (2002), 28–35.