Byblos

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Bublos | Greek | Βύβλος |

| Byblus | Latin | |

| Jubayl | Arabic | جبيل |

| Jebeil | Arabic | جبيل |

| Gibelet | Crusades | |

| Giblet | Crusades | |

| gbl | Syriac | ܓܒܠ |

| Gebal | Phoenician | |

| Geval, Gebal | Hebrew Bible | גבל |

| Kebny | Egyptian hieroglyphic records going back to the 4th-dynasty pharaoh Sneferu |

|

| kbn, kpny, kbny | Egyptian | |

| Gubla | Akkadian cuneiform Amarna letters to the 18th-dynasty pharaohs Amenhotep III and IV |

|

| Gubla | Babylonian |

Byblos is located on the Phoenician coast and has a long history of occupation dating back more than 7000 years. The city played an important role in Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange. The very name for the Bible is derived from Byblos, as Egyptian papyrus was shipped to Greece via this port ( Martha Sharp Joukowsky in Meyers et al. 1997). Byblos thus occupies a unique place in Near Eastern archaeology and intellectual history, serving as a nexus between Egypt, the Levant, and the Greek world.

Byblos is a seaport located in Lebanon, on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, at the foot of the Lebanese mountains 60 km (25 mi.) north of Beirut on the Tripoli highway, (approx. 34° N, 36° E). The site has been known throughout its long history in several variants on its name: in modern Arabic as Jebail, Jebeil, Jubail; by the Crusaders as Gibelet; in biblical Hebrew as Gebal (1 Kgs. 5:18,32, Ez. 2 7:9, Jos. 13:5) in Egyptian as kbn, kpny, kbny; and in Babylonian as Gubla. The Greeks probably gave the city its name at about the end of the second millennium BCE — the Greek bublos, "papyrus scroll." Egyptian papyrus came to Greece through Phoenicia and Byblos for transshipment to the Aegean area. The English word Bible is derived through medieval Latin from the Greek ta Biblia, "the books".

In Naples, Italy, in 1881, a sandstone bust from Byblos surfaced in the antiquities market. It was of Osorkon I, pharaoh of the twenty-second dynasty (924-889 BCE), and it had on it a cartouche and a Phoenician alphabetic dedicatory inscription by King Elibaal of Byblos. It was sold in Paris in 1910 and subsequently donated to the Louvre Museum (where it remains); in 1925 Rene Dussaud translated the inscription. Also in the Drehem archives (the Ur III archives in Drehem, just south of Nippur) and dated to about 2050 BCE is the earliest cuneiform economic text referring to Byblos, mentioning Ibdadi, the ensi (a title meaning "ruler" in Sumerian) of Byblos (Ward, 1963).

In 1860 the French savant Ernest Renan, representing Napoleon III's mission in Phoenicia, located Byblos, made several soundings (even though twenty-nine houses occupied the site), and sketched the site and the sacred spring, the arched and roofed "Pool of the Phoenician Princess." In 1864 he published his findings and inscriptions, including the Renan bas-relief now also in the Louvre. The city was recognized as Byblos certainly by 1899. French archaeologist Pierre Montet undertook four campaigns (1921-1924) there, which uncovered the so-called Egyptian and Syrian temples (later identified as the single Temple of Baalat Gebal), along with three mutilated limestone colossi and many Egyptian Old Kingdom inscriptions, which he published in 1928 (Montet, 1928). A landslide in 1922 revealed the sarcophagus of a Byblite king with gifts from the Egyptian pharaoh Amenemhat III (c. nineteenth century BCE); eight other tombs were excavated in this royal necropolis. In 1930 the Lebanese government expropriated the houses built on the site. In 1926 the commissioner of France in Syria reopened the excavations, sponsored by the Lebanese government and the French Academy of Inscriptions and under the direction of French archaeologist Maurice Dunand. Dunand excavated from 1928 until the Lebanese civil war in the 1970s, under the auspices of the Lebanese government and the Louvre.

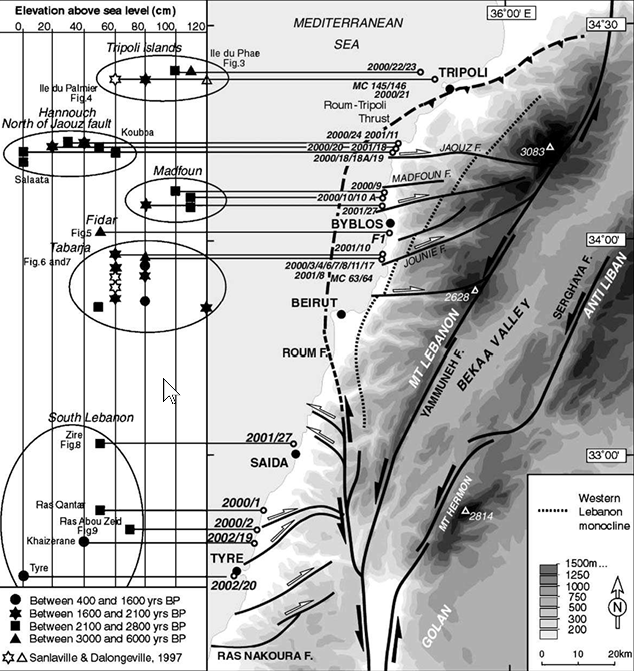

- Fig. 2 Simplified structural map

of Lebanon from Morhange et al (2006)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Simplified structural map of Lebanon and studied sites.

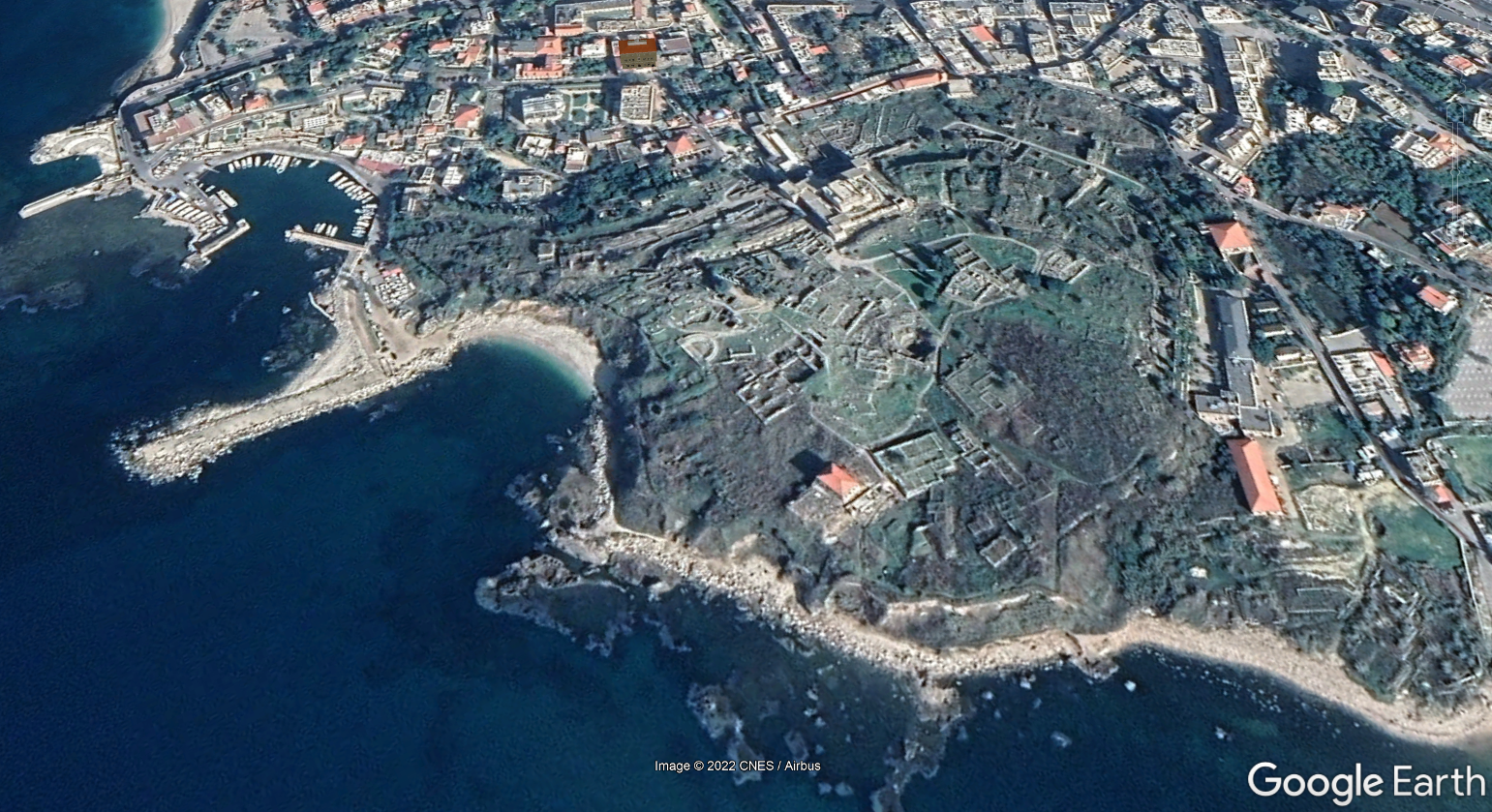

Morhange et al (2006) - Byblos in Google Earth

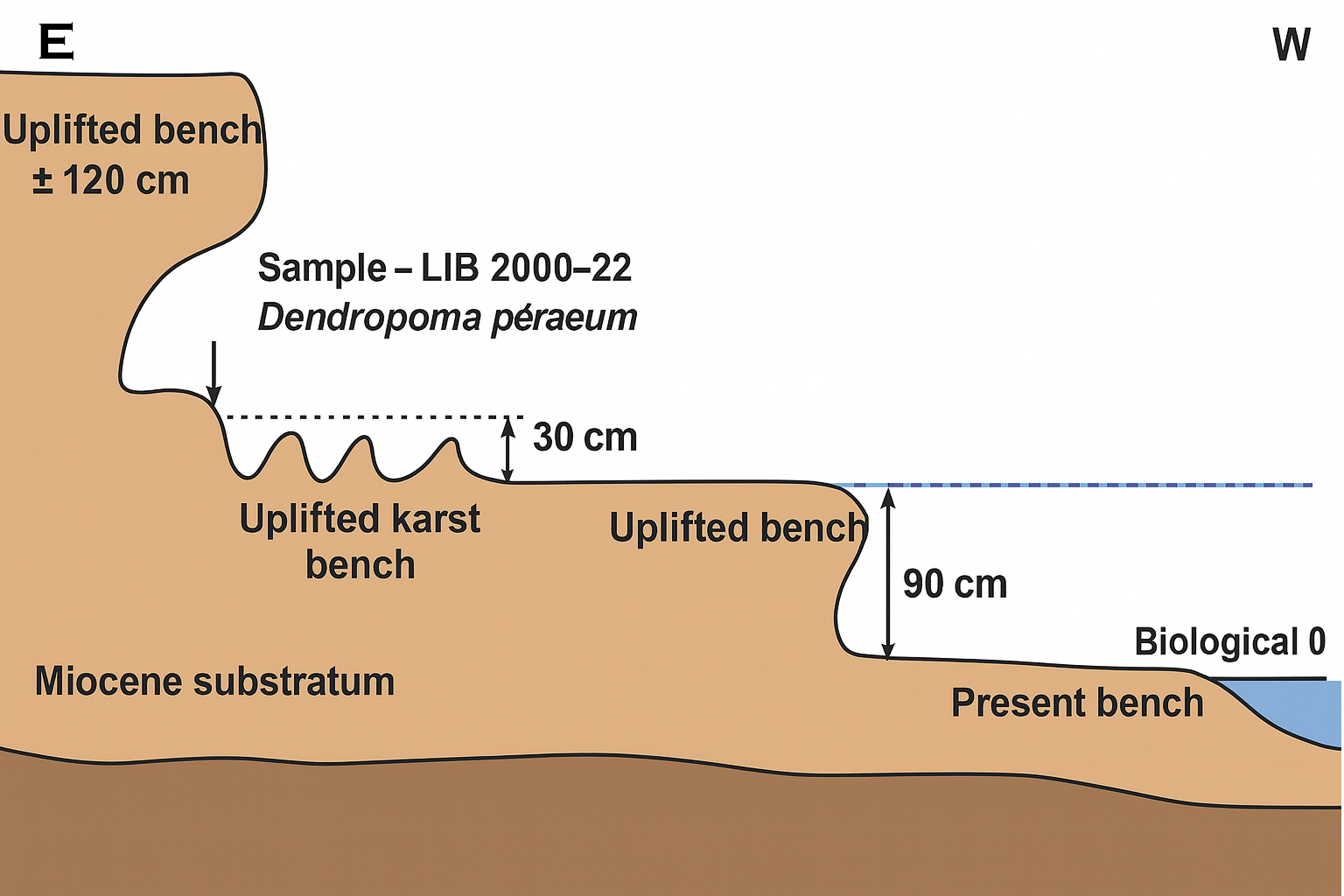

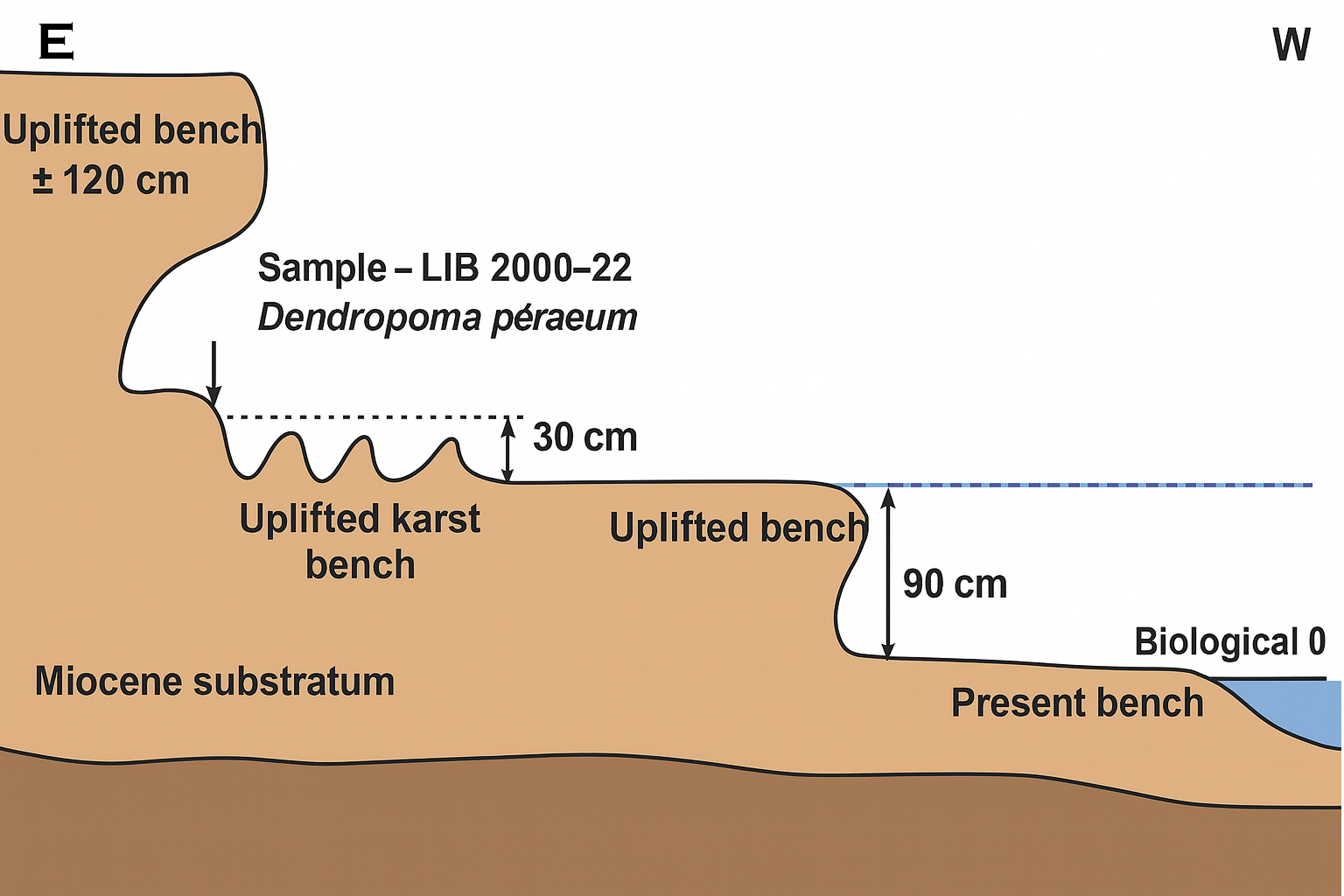

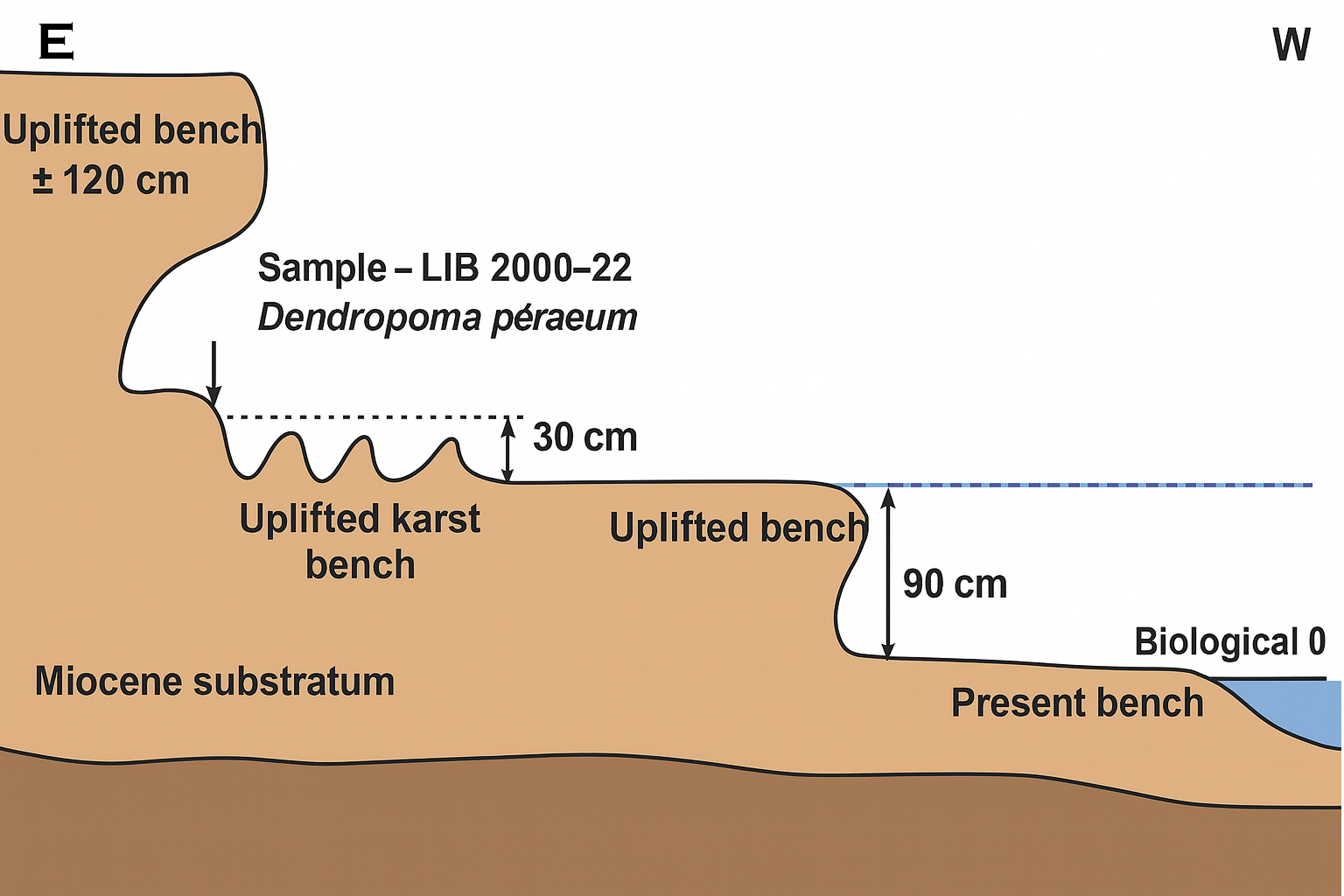

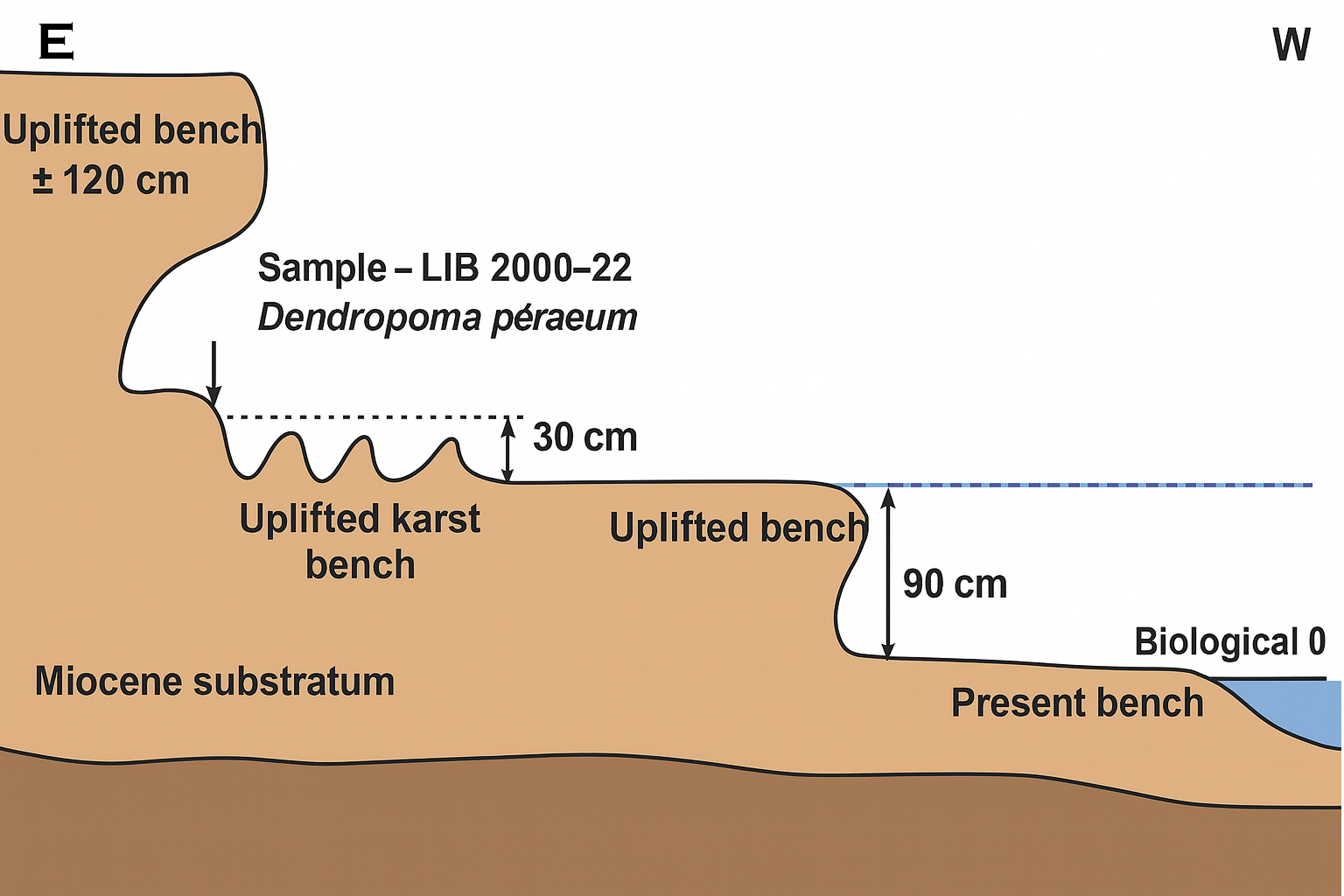

- Fig. 3 Drawing of Raised Benches

at Ilot du Phare (Tripoli) from Morhange et al (2006)

Figure 3

Figure 3

On the northern part of Ilot du Phare (Tripoli), marks of a double raised bench have been preserved. The lowest step, at approx. +1 m (above present MSL), comprises Dendropoma dated 2630 ± 35 BP (403-265 cal. BC). The outer part of the upper step, at approx. +1.2 m, has been dissected by erosion, but on the inner part, that corresponds to the base of a tidal notch, a thin cover of in situ Dendropoma petraeum shells have been collected and dated 5975 ± 40 BP (4514-4339 cal. BC).

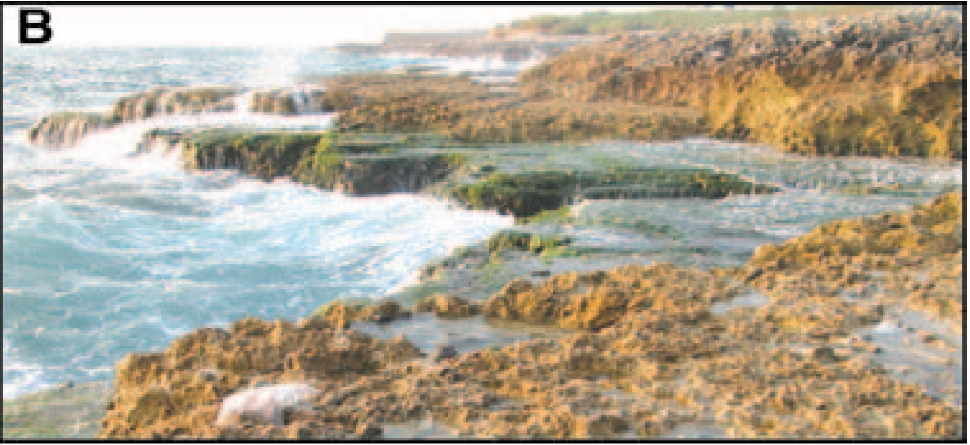

Morhange et al (2006) - Fig. 4 Photo of raised shoreline

at Ilot du Phare from Morhange et al (2006)

Figure 4

Figure 4

On Ilot du Phare, a double, stepped biological bioconstruction has been preserved on the walls of a rock fissure, at approx. +1 and +1.3 m, respectively (arrows). The upper rim could not be reached for sampling, but the two organic cornices clearly indicate, with an uncertainty of ± 0.2 m, the position of the biological sea level corresponding to two former shorelines (Photo G672). The lower rim was dated 2630 ± 35 BP (403-265 cal. BC).

Morhange et al (2006) - Panoramic View of Byblos

- Photo by Garen Bosnoyan (2022)

Panoramic View of Byblos

Panoramic View of Byblos

Courtesy of Garen Bosnoyan (2022)

Ambraseys (2009) discussed an inscription found in Byblos which may allude to the 303–306 CE Eusebius Martyr Quake,

There is also an inscription from an altar in Byblus that records the survival of one Apollodorus after an earthquake Dussaud (1896:299). The inscription is dated by Seyrig to the second or third century, which would seem to indicate that it is not connected with this earthquake (H. Seyrig, personal communication 5 July 1972). However, since provincial epigraphy is often slower to change than that in major centres, and there is no other earthquake recorded for this location during the second or third century, the inscription has been very tentatively allocated to this event.

It is an oversimplification to attribute the tsunami triggering mechanism solely to earthquake-induced seabed faulting. In some areas sediment slides may be the dominant factor of tsunami generation. In other areas, extreme storm surges leave facies which cannot be unequivocally differentiated from tsunami signatures. For example in Haifa, northern Israel a huge block was projected onto the beach during the severe storm of 2002 (Galili, pers. commun., Fig. 14). Although present day storms in the Mediterranean may displace blocks of significant size, a tsunami origin seems a feasible explanation for most of the megablocks encountered on the Lebanon coasts.

A review of the vertical movements having affected Lebanon during the late Holocene shows that tectonic uplift of the coastal areas occurred around 3000 yr BP, in the 6th century AD, and possibly in the 10th to 11th centuries AD (Pirazzoli 2005, Morhange et al., submitted). It is important to note that none of these periods coincides with the megablock dates. This suggests that they were possibly projected by waves coming from outer tsunamigenic areas. It is surprising to note that the 4th and 5th centuries AD (e.g. the tsunami of 365 AD), a period of tectonic paroxysm in the eastern Mediterranean (Pirazzoli 1986, Pirazzoli et al. 1996), are not represented by the dated megablocks.

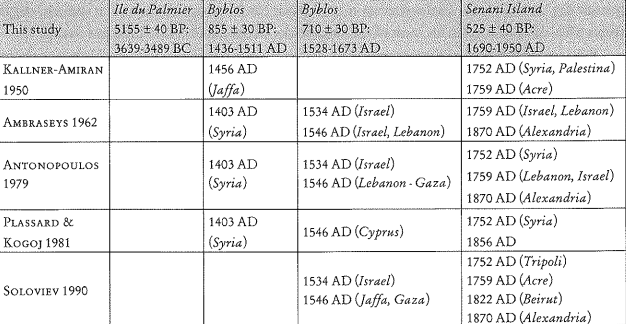

Correlation with chronicled tsunami events is given in Table 1. Tsunami and earthquake catalogues do not provide any information on the mid-Holocene date from Ile du Palmier. Conversely, displacement of the Byblos megablocks are consistent with the 1456 AD, and 1534 or 1546 AD tsunami events, whereas the dated Senani island megablock could have been projected by any of the tsunami events reported in the area in 1752,1759,1822,1856, or 1870 AD.

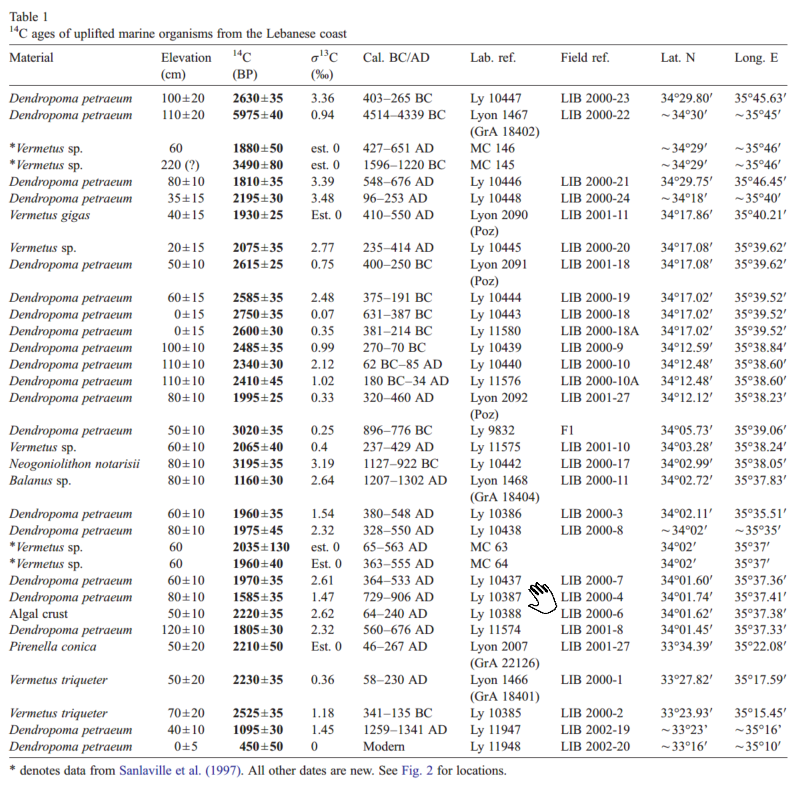

Table 1

Table 1Tentative correlation between radiocarbon dates obtained from megablocks sampled on the Lebanon coast and historical tsunamis reported by catalogues for the Eastern Mediterranean (coastal areas indicated by catalogues as tsunami-affected are added in brackets).

Morhange et al (2006)

Morhange et al. (2006:91) noted that

A review of the vertical movements having affected Lebanon during the late Holocene shows that tectonic uplift of the coastal areas occurred around 3000 yr BP, in the 6th century AD, and possibly in the 10th to 11th centuries AD (Pirazzoli 2005, Morhange et al., submitted).

Carayon et al. (2011) discussed

6 cores taken in Byblos — 2 in the northern harbor and 4 in the

bay of El-Skhiny. The study focused on geomorphic evolution of

the harbor. Core profiles were not presented. There is no mention

of tsunamogenic evidence.

Morhange et al. (2006:91) noted

that

A review of the vertical movements having affected Lebanon during the late Holocene shows that tectonic uplift of the coastal areas occurred around 3000 yr BP, in the 6th century AD, and possibly in the 10th to 11th centuries AD (Pirazzoli 2005, Morhange et al., submitted).

Morhange et al. (2006:91) noted that

A review of the vertical movements having affected Lebanon during the late Holocene shows that tectonic uplift of the coastal areas occurred around 3000 yr BP, in the 6th century AD, and possibly in the 10th to 11th centuries AD (Pirazzoli 2005, Morhange et al., submitted).

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Levantine Coast from Turkey to Lebanon |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Lebanese Coast |

Figure 3

Figure 3On the northern part of IIe du Phare (Tripoli), marks of a double raised bench have been preserved. The lowest step, at approx. +1 m (above present MSL), comprises Dendropoma dated 2630 ± 35 BP (403-265 cal. BC). The outer part of the upper step, at approx. +1.2 m, has been dissected by erosion, but on the inner part, that corresponds to the base of a tidal notch, a thin cover of in situ Dendropoma petraeum shells have been collected and dated 5975 ± 40 BP (4514-4339 cal. BC). Click on image to open in a new tab Morhange et al. (2006b) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Lebanese and Syrian Coast |

|

- Earthquake Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Levantine Coast from Turkey to Lebanon |

|

VIII |

- Earthquake Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Lebanese Coast |

Figure 3

Figure 3On the northern part of IIe du Phare (Tripoli), marks of a double raised bench have been preserved. The lowest step, at approx. +1 m (above present MSL), comprises Dendropoma dated 2630 ± 35 BP (403-265 cal. BC). The outer part of the upper step, at approx. +1.2 m, has been dissected by erosion, but on the inner part, that corresponds to the base of a tidal notch, a thin cover of in situ Dendropoma petraeum shells have been collected and dated 5975 ± 40 BP (4514-4339 cal. BC). Click on image to open in a new tab Morhange et al. (2006b) |

|

IX |

- Earthquake Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Uplift | Lebanese and Syrian Coast |

|

VIII |

Carayon, N. and N. Marriner (2011). "Geoarchaeology of Byblos, Tyre, Sidon and Beirut." Rivista di studi fenici XXXIX: 55-66.

Dussaud, R. (1897). "VOYAGE EN SYRIE Octobre-novembre 1896 NOTES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES." Revue archéologique 30: 305-357.

Elias, A., et al. (2007). "Active thrusting offshore Mount Lebanon: Source of the tsunamigenic A.D. 551 Beirut-Tripoli earthquake." Geology 35(8): 755-758.

Morhange, C., et al. (2006a). "Late Holocene relative sea-level changes in Lebanon, Eastern Mediterranean." Marine Geology 230(1): 99-114.

Morhange, C., Marriner, Nick, Pirazzoli, P. (2006b). "Evidence of late Holocene tsunami events in Lebanon." Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie 146: 81-95.

Okada, Y. (1985). "Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space." Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 75: 1135-1154.

Sanlaville P, Dalongeville R, Bernier P, Evin J (1997) The Syrian coast: a model of Holocene coastal evolution. J Coast Res 13(2): 385–396 - JSTOR

Sarieddine, K. (2022). Seismic Interpretation and Analysis of the Messinian Salt system Offshore Lebanon. Msc Thesis, American University of Beirut. 121p

SHALIMAR Oceanographic cruise 27/09/2003 - 26/10/2003 Data Page

Sivan, D., Schattner, U., Morhange, C., Boaretto, E. (2010). "What can a sessile mollusk tell about neotectonics?" Earth and Planetary Science Letters 296(3): 451-458.

Albright, William Foxwell. "The Eighteenth-Century Princes of Byblos

and the Chronology of thee Middle Bronze. " Bulletin of the American

Schools of Oriental Research, no . 17 6 (Nov. 1989): 38-46.

Breasted, James H, Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from

the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest. 5 vols. Chicago, 1906-1907.

Dunand , Maurice. Fouilles de Byblos. 5 vols. Paris, 1937-1958.

Dunand , Maurice. "Rapport preliminaire sur les fouilles de Byblos."

Bulletin duMusiede Beyrouth 9 (1949-1950): 53-74 ; 12 (1955): 7-23 ;

13 (1956): 73-86 ; 16 (1964): 69-85. Reports by the site's most prolific excavator.

Dunand , Maurice. Byblos: Its History, Ruins, and Legends. 2d ed. Beirut,

1968.

Jidejian, Nina. Byblos through the Ages. Beirut, 1968. Comprehensive

history of Byblos through tine ages, with strong coverage of ancient,

classical, and contemporary references. Includes a good bibliography

through the late 1960s.

Joukowsky, Mardia Sharp. The Young Archaeologist in the Oldest Port

City in the World. Beirut, 1988, Children's book exploring the history

and archaeology of Byblos

Montet, Pierre. Byblos et I'Egypte: Quatre campagnes de fouilles d Gebeil

1021-1024. Paris, 1929. Comprehensive publication of four early expeditions.

Pritchard, James B. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Tes~

lament. 3d ed, with supp. Princeton, 1978.

Renan, Ernest. Mission de Phenicie. Paris, 1864. One of the earliest

works on Phoenician sites.

Tufhell, Olga, and William A. Ward. "Relations between Byblos,

Egypt, and Mesopotamia at the End of the Third Millennium B.C. "

Syria 43 (1966): 165-241 . Specialized study of the Montet jar and

its contents; see Ward and Dever (below) for a recent study of the

jar.

Ward, William A. "Egypt and the East Mediterranean in the Early

Second Millennium B. C. " Or 30 (1961): 22-45 , 129-155.

Ward, William A. "Egypt and the East Mediterranean from Pre-Dynastic Times to die End of the Old Kingdom. " Journal of Economic

and Social History of the Orient 6 (1963): 1-57. Survey of political

and cultural relations between Egypt, Asia, and the Aegean world.

Ward, William A., and William G. Dever. Studies on Scarab Seals. Vol.

3, Scarab Typologies and Archaeological Context. San Antonio, 1994.

See chapter 4 for the most recent study of the Montet jar and its

contents.

| Description | Image | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ilot du Palmier megablock |

Figure 5

Figure 5Ilot du Palmier is characterised by numerous megablocks, 50 to 100 m from the present coastline. The volume of the photographed megablock is approx. 3.5 m3. Superficial Dendropoma crusts yielded a radiocarbon age of 5155 ± 40 BP (3639-3489 cal. BC). Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 5 - Morhange et al (2006) |

| Senani island megablock |

Figure 6

Figure 6On Senani island, megablocks are scattered on the windward side. Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 6 - Morhange et al (2006) |

| Senani island megablock |

Figure 7

Figure 7A large tsunami block on Senani island approx. 30m3 and 10 m from the shoreline is encrusted with biological remains dated 525 ± 40 BP (1690-1950 cal. AD). Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 7 - Morhange et al (2006) |

| South of Enfe megablock |

Figure 8

Figure 8South of Enfe, rare cyclopean blocks arc covered by Dendropoma. Photo of a 12 m3 block radio-carbon dated to modern times (Ly 11578). Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 8 - Morhange et al (2006) |

| Byblos megablock |

Figure 9

Figure 9Byblos, a 5.5 m3 block projected towards the base of the ancient sea wall, encrusted with upper subtidal vermetid shells, dated 855 ± 30 yr BP (1436-1511 cal. AD). Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 9 - Morhange et al (2006) |

| Byblos megablock |

Figure 10

Figure 1020 m3 conglomerate block at Byblos, dated 710 ± 30 yr BP (1528-1673 cal. AD). Morhange et al (2006) |

Fig. 10 - Morhange et al (2006) |

Summary. We present new evidence of megablocks left by extreme waves around the Tripoli islands and Byblos, northern Lebanon. On Ile du Palmier, megablocks have been projected a distance of 50 to 100 m from the shoreline. A Dendropoma bioconstruction was sampled from the outer part of one of the blocks, approx. 3.5 m3 in size and located 60 m from the shore. It dates a mid-Holocene event (5155 ± 40 14C years BP, or 3639-3489 cal. yr BC) deriving from the west. On the nearby island of Senani, numerous megablocks are scattered on the flat island surface. Their position again suggests projection by westerly waves. One of the blocks, approx. 30 m3 in size and 10 m from the shoreline, yielded a radiocarbon age of 525 ± 40 BP (1690-1950 cal. AD). Further south, at Byblos, a 5.5 m3 block projected towards the base of the ancient sea wall, was encrusted with upper subtidal vermetid shells, constrained to 855 ± 30 yr BP (1436-1511 cal. AD). A nearby 20 m3 conglomerate block was dated 710 ± 30 yr BP (1528-1673 cal. AD). A tsunami origin seems a feasible explanation for most of the megablocks encountered. Review of the vertical movements having affected the Lebanese coast during the late Holocene shows that major uplift of coastal areas occurred around 3000 yr BP, in the 6th century AD, and possibly in the 10th to 11th centuries AD. None of these periods coincide with the megablock dates, suggesting that the tsunami waves derived from outer tsunamigenic areas.

- from Morhange et al. (2006a)

- Caveat: Generated from GPT 5 - not fully QCed

| Field Ref | Material | Elevation (cm) | Radiocarbon Age (BP) | Cal. BC/AD | Lab Ref | Latitude (°) | Longitude (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIB 2000-23 | Dendropoma petraeum | 100 ± 20 | 2630±35 | 403–265 BC | Ly 10447 | 34.49667 | 35.76050 |

| LIB 2000-22 | Dendropoma petraeum | 110 ± 20 | 5975±40 | 4514–4339 BC | Lyon 1467 (GrA 18402) | 34.50000 | 35.75000 |

| MC 146 | *Vermetus sp. | 60 | 1880±50 | 427–651 AD | MC 146 | 34.48333 | 35.76667 |

| MC 145 | *Vermetus sp. | 220 (?) | 3490±80 | 1596–1220 BC | MC 145 | 34.48333 | 35.76667 |

| LIB 2000-21 | Dendropoma petraeum | 80 ± 10 | 1810±35 | 548–676 AD | Ly 10446 | 34.49583 | 35.77417 |

| LIB 2000-24 | Dendropoma petraeum | 35 ± 15 | 2195±30 | 96–253 AD | Ly 10448 | 34.30000 | 35.66667 |

| LIB 2001-11 | Vermetus gigas | 40 ± 15 | 1930±25 | 410–550 AD | Lyon 2090 (Poz) | 34.29767 | 35.67017 |

| LIB 2000-20 | Vermetus sp. | 20 ± 15 | 2075±35 | 235–414 AD | Ly 10445 | 34.28467 | 35.66033 |

| LIB 2001-18 | Dendropoma petraeum | 50 ± 10 | 2615±25 | 400–250 BC | Lyon 2091 (Poz) | 34.28467 | 35.66033 |

| LIB 2000-19 | Dendropoma petraeum | 60 ± 15 | 2585±35 | 375–191 BC | Ly 10444 | 34.28367 | 35.65867 |

| LIB 2000-18 | Dendropoma petraeum | 0 ± 15 | 2750±35 | 631–387 BC | Ly 10443 | 34.28367 | 35.65867 |

| LIB 2000-18A | Dendropoma petraeum | 0 ± 15 | 2600±30 | 381–214 BC | Ly 11580 | 34.28367 | 35.65867 |

| LIB 2000-9 | Dendropoma petraeum | 100 ± 10 | 2485±35 | 270–70 BC | Ly 10439 | 34.20983 | 35.64733 |

| LIB 2000-10 | Dendropoma petraeum | 110 ± 10 | 2340±30 | 62 BC–85 AD | Ly 10440 | 34.20800 | 35.64333 |

| LIB 2000-10A | Dendropoma petraeum | 110 ± 10 | 2410±45 | 180 BC–34 AD | Ly 11576 | 34.20800 | 35.64333 |

| LIB 2001-27 | Dendropoma petraeum | 80 ± 10 | 1995±25 | 320–460 AD | Lyon 2092 (Poz) | 34.20200 | 35.63717 |

| F1 | Dendropoma petraeum | 50 ± 10 | 3020±35 | 896–776 BC | Ly 9832 | 34.09550 | 35.65100 |

| LIB 2001-10 | Vermetus sp. | 60 ± 10 | 2065±40 | 237–429 AD | Ly 11575 | 34.05467 | 35.63733 |

| LIB 2000-17 | Neogoniolithon notarisii | 80 ± 10 | 3195±35 | 1127–922 BC | Ly 10442 | 34.04983 | 35.63417 |

| LIB 2000-11 | Balanus sp. | 80 ± 10 | 1160±30 | 1207–1302 AD | Lyon 1468 (GrA 18404) | 34.04533 | 35.63050 |

| LIB 2000-3 | Dendropoma petraeum | 60 ± 10 | 1960±35 | 380–548 AD | Ly 10386 | 34.03517 | 35.59183 |

| LIB 2000-8 | Dendropoma petraeum | 80 ± 10 | 1975±45 | 328–550 AD | Ly 10438 | 34.03333 | 35.58333 |

| MC 63 | *Vermetus sp. | 60 | 2035±130 | 65–563 AD | MC 63 | 34.03333 | 35.61667 |

| MC 64 | *Vermetus sp. | 60 | 1960±40 | 363–555 AD | MC 64 | 34.03333 | 35.61667 |

| LIB 2000-7 | Dendropoma petraeum | 60 ± 10 | 1970±35 | 364–533 AD | Ly 10437 | 34.02667 | 35.62267 |

| LIB 2000-4 | Dendropoma petraeum | 80 ± 10 | 1585±35 | 729–906 AD | Ly 10387 | 34.02900 | 35.62350 |

| LIB 2000-6 | Algal crust | 50 ± 10 | 2220±35 | 64–240 AD | Ly 10388 | 34.02699 | 35.62300 |

| LIB 2001-8 | Dendropoma petraeum | 120 ± 10 | 1805±30 | 560–676 AD | Ly 11574 | 34.02417 | 35.62217 |

| LIB 2001-27 (Tyre) | Pirenella conica | 50 ± 20 | 2210±50 | 46–267 AD | Lyon 2007 (GrA 22126) | 33.57317 | 35.36800 |

| LIB 2000-1 | Vermetus triqueter | 50 ± 20 | 2230±35 | 58–230 AD | Lyon 1466 (GrA 18401) | 33.46367 | 35.29317 |

| LIB 2000-2 | Vermetus triqueter | 70 ± 20 | 2525±35 | 341–135 BC | Ly 10385 | 33.39883 | 35.25750 |

| LIB 2002-19 | Dendropoma petraeum | 40 ± 10 | 1095±30 | 1259–1341 AD | Ly 11947 | 33.38333 | 35.26667 |

| LIB 2002-20 | Dendropoma petraeum | 0 ± 5 | 450±50 | Modern | Ly 11948 | 33.26667 | 35.16667 |