Abou Karaki (1987)

Abbreviations used by Abou Karaki (1987) and Error Types as defined by Abou Karaki (1987) and Abou Karaki et al (2022)

| Abbr | Ref | Abbr | Ref | Abbr | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALGH1 | ALSINAWI AND CHALIB (1975) | AMBR1 | AMBRASEYS (1962-A) | AMBR2 | AMBRASEYS (1962-B) |

| BM1 | BEN-MENAHEM (1979) | BM2 | BEN-MENAHEM (1981) | BMNV | BEN-MENAHEM,NUR, VERED (1976) |

| CSEM | CENTRE SISMOLOGIQUE EURO-MEDITERRANIEN - STRASBOURG | EL-ISA | EL-ISA (1981) | HAM | HAMMOND (1981) |

| HRVD | HARVARD | IPGS | INSTITUT DE PHYSIQUE DU GLOBE DE STRASBOURG | IPRG | INSTITUT FOR PETROLIUM AND GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH-TEL-AVIV |

| ISC | INTERNATIONAL SEISMOLOGICAL CENTRE | KAR | KARNIK (1971) | NAJA | CE TRAVAIL |

| NRA | NATURAL RESOURCES AUTHORITY - AMMAN | PRETA | POIRIER, ROMANOWICZ, TAHER (1980) | PTAH | POIRIER, TAHER (1980) |

| SEIB | SEIBERG (1932) | TAFIA | TAHER (1979) - VERSION ARABE | TAHF | TAHER (1979) - VERSION FRANCAISE |

| THOL | THOLOZAN (1879) | UNJ | UNIVERSITY OF JORDAN - AMMAN (STATION SISMOLOGIQUE) | USGS | UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY |

| WILL | WILLIS (1928-A) |

| Error Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Doublets - Instead of one genuine original earthquake, the date of which is eventually given in two different calendar systems, the earthquake is wrongly associated with two different dates given in one of the two calendar systems, e.g. the earthquake of the year 598 AH (After Hijra Muslim lunar Calendar) which is the same of 1202 AD, figuring in a catalog as two independent earthquakes associated respectively with the years 598 AD and 1202 AD, or, although less frequently, to 598 AH and 1202 AH)). Tens of such “earthquakes “that we call “false earthquake twins, or simply, twins” figures in Willis’s list in his work of 1928, these errors were copied and passed on within the global seismicity lists of Seiberg in 1932 (Willis, 1933), such errors were corrected partially (rather inaccurately, and too late) in (Willis, 1928) then (Ambraseys, 1962)Abou Karaki et al. (2022) |

| II | due to imprecision in calendaric conversions between two different calendars -

This type of errors refers to twins resulting from an inaccurate date transformation between calendar systems. This provides an explanation to the case of many major earthquakes with reasonably similar locations, effects, and descriptions occurring within ±2 years from each other in a given section of the fault, a clear example on this is found in the work of Taher (1979) (Taher, 1979). The earthquake of the month of Ramadan 130 AH is wrongly associated to the year 747 AD the correct year corresponding to the month of Ramadan in the year 130 or 131 AH should be 748 or 749 AD In some existing or future “complete” catalogs the years 746, 747, 748 and 749 AD would be listed as major earthquakes happening in almost the same geographic area. So the existence of two major earthquakes occurring in the same area and associated with the years 747 AD and 748 AD if given in a historical seismicity list would be the result of a type II error.Abou Karaki et al. (2022) |

| III | Errors due to listing an earthquake as a BCE date when it was actually a CE date or vice versa |

| IV | due to imprecision in calendaric conversions between two different calendars -

This is another source of timing errors potentially leading to multiple duplications in the historical seismicity catalogs. It refers to the difficulty to determine the exact year in the original manuscripts and historical seismicity primary sources, due to the frequent use of abbreviated numbers to represent the date in the original text. In many Arabic original manuscripts the full number representing the year of occurrence of a given event is in fact given partially. So a statement like “there was an earthquake in the year 37” might mean 37 AH or 137, 277,..., or 1437 AH and so on. Victims of such errors are typically those who depend upon translated short pieces of an original text. To overcome this problem, it was often necessary for us to perform the time consuming task of carefully reexamining a number of pages before and/or after a given purely pertinent description of the effects of an earthquake to find or clearly deduce its correct year of occurrence.Abou Karaki et al. (2022) |

| V | Manuscripts Reproduction Related Errors -

The only way to reproduce manuscripts was to recopy them manually, often by others than the original author. Different versions exist derived from an original work. The famous work of the Muslim tenth century paleographer Jalal-Eddine Al-Suyouti exists in twenty copies of variable qualities (Al-Sadani, 1971) p. XVII). One of them, namely that of the British Museum library, Ms. No. 5872, is known to be incomplete and to have some lack of accuracy problems (Al-Sadani, 1971) p. XIV). To illustrate this kind of difficulties by an example, the earthquake of 11 March 1068 AD is said to have destroyed the totality of Ramla except 2 “houses” (in Arabic DARRAN) in one manuscript or except 2 “lanes” (DARBAN) in another copy. The process of copying tend to produce, propagate and amplify errors. However this is not the only aspect of the problem, the ancient Arabic writing style is much more difficult to read and interpret. Recognizing the correct signification of a written word which could have a number of very different meanings is a matter of habit, training and context. Old style writing means more difficulties at least as far as the habit factor of the reader is concerned.Abou Karaki et al. (2022) |

| VI | Erroneous Seismological Quantifications Based Upon Inaccurately Translated or Understood Texts -

This is best represented by the following case; Taher (1979) (Poirrier & Taher, 1980) presented “A full corpus of texts from Arabic sources and a summary French translation”. This work is considered to be “By far the most valuable compilation of material on the seismicity of the region” Ambraseys et al. (Ambraseys et al., 1994, p.7). Although we agree with the general ideas implicated by the upper mentioned statement, it is necessary to say that some parts of Taher’s translations were potentially very misleading from the seismological point of view. In his revision of the area’s seismicity, Abou Karaki (1987) gave the following example concerning the earthquake of the year 425 AH = 1033 AD, Taher’s French translation of part of the Arabic text concerning that earthquake began as follows “Cette annèe un très violent tremblement de terre ravage a la Syrie et l’Egypt" "This year a very violent earthquake ravaged Syria and Egypt“(Taher, 1979) p. 35). A more accurate and faithful translation of the Arabic text would in fact be “This year there was an increase (or multiplication) of earthquakes in Syria and Egypt“(Abou Karaki, 1987, p.131). It is clear that the first seismologically erroneous translation would give a much higher magnitude for “the earthquake“, if a magnitude calculation operation based on that translation and the “radius of perceptibility” concept is “committed”. The work of Taher (1979) was the basis of the parametric- macroseismicity information catalog of Poirrier and Taher (1980). Despite the inaccuracies “It nevertheless remains the most authorative and reliable list of events in the region up to 1800, thanks to its reliance on primary sources” that was the opinion expressed by Ambraseys et al. (1994). However we think that primary sources when they exist are not quite enough, it should be mentioned here that “Taher’s work is the starting point for (Ambraseys et al., 1994) retrieval and reassessment of historical information” (Ambraseys et al., 1994, p. 11). Our revision of Poirrier and Taher’s work of 1980, and the application of Abou Karaki’s algorithm for the detection of errors in the historical seismicity catalogs of the Arab region, (Abou Karaki, 1987, 1992, 1995a) allowed us to discover that 59 dates out of 240 ones associated with the historical earthquake‘s list of Poirrier and Taher (1980) are in fact erroneous. Some quantifications and interpretations are not less erroneous and misleading, and have already injected new ambiguities in the historical seismicity domain of this area. One example is provided by examining the following statement concerning, once more, the earthquake of March, 18th 1068 AD in Poirrier and Taher’s remark “d” (Poirrier & Taher, 1980) p. 2199 (which should be “c” by the way) they wrote “Al Djawzi reports that at Khaibar, the ground opened up and treasures were revealed. As Sayouti reports that at Tayma, the ground opened up. These features of ground deformation, usually restricted to the epicentral zone, plus the widespread destruction in Arabia suggest that this was an intraplate earthquake with its epicenter in Arabia despite the fact that there were sea waves on the Egyption and Israeli coasts. Perhaps we are dealing here with two close seisms”. Independently “?” of this statement Ambraseys and Melville (1989), and later Ambraseys et al. (1994), also enhanced this ambiguity by presenting a somewhat “artificially” strong case for the major 1068 AD earthquake along with two other less “well” documented ones (873 AD, 1588 AD) to be considered as intraplate earthquakes taking place inside northwestern Arabia, more than 150 to 250 km east of the nearest plate boundary zone in the area. This aspect along with other various sources of errors will be briefly discussed under our description and revision of the following case.Abou Karaki et al. (2022) |

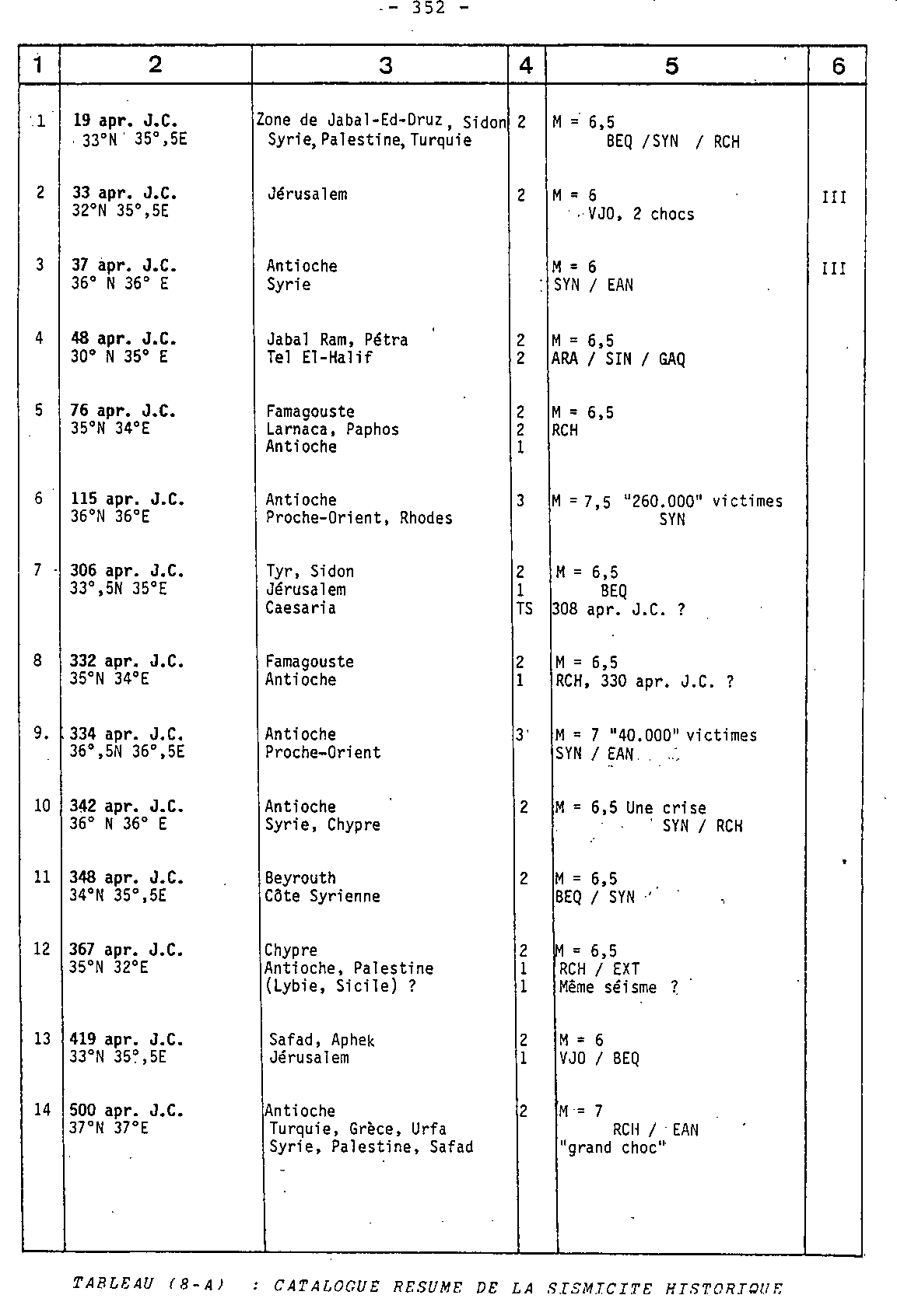

Original 1987 Catalog in French

Original 1987 Catalog Machine translated to English

Major Historical DST Earthquakes - Abou Karaki et al (2022)

Abou Karaki, N. (1987). Synthese et carte sismotectonique des pays de la bordure Orientale de la Mediterranae: sismicite du systeme de failles du Jourdain-Mer-Morte, University of Strasbourg, France. Ph.D. - reproduced with permission

The Historical Seismicity of the Jordan Dead Sea Transform Fault System - Research Gate Project

Abou Karaki, N., Closson, D., Meghraoui, M. (2022). Seismological and Remote Sensing Studies in the Dead Sea Zone, Jordan 1987–2021. In: Al Saud, M.M. (eds) Applications of Space Techniques on the Natural Hazards in the MENA Region. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88874-9_25