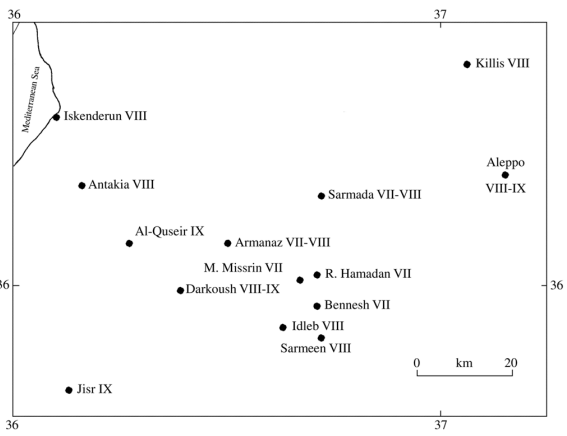

AD 1822 Aug 13 Southeastern Anatolia

This earthquake was the largest to occur at the junction of the Dead Sea fault zone with the East Anatolian fault during the last five centuries The earthquake

was felt from the coast of the Black Sea to Gaza and it

was followed by a long aftershock sequence. The shock

almost entirely destroyed the region between Gaziantep

and Antakya in Turkey and Aleppo and Han Sheikhun

in northwestern Syria, killing a very large number of

people.

Slight shocks, reported mainly from Aleppo and

Antakya, began on 5 August and continued intermittently until 12 August, but, since they were like many

others that had been experienced in the past, they caused

no alarm to the inhabitants. At 20 h 10 m on 13 August a

strong shock was felt in the region bounded by Lattakiya,

Aleppo and Antakya: this caused considerable concern

and warned the people of what was to follow. The main

shock happened 30 minutes later in three phases lasting

altogether 40 seconds. A flash of light was seen in the sky

over Aleppo, Antakya, Suaidiya and Iskenderun. After a

short pause, the main shock was followed for about 8 minutes by successive shocks, about 30 in all, each of short

duration but of damaging intensity; in Aleppo, Antakya

and Aintab these were as strong as the main shock and

completed the destruction and caused the bulk of the loss

of life.

The most northerly part of the area destroyed

was that of Gaziantep and Atmanlu. The chief town of

Aintab was almost completely destroyed: most houses

collapsed and the remainder were rendered uninhabitable; mosques, medreses, the old castle (already in ruins),

part of the old aqueduct and the surrounding villages

were destroyed with great loss of life. The villages of

Sagce, Araplar, Burc and Kehriz were destroyed and

many people and animals were killed. Survivors sheltered

in tents and huts outside the villages for a long time after

the earthquake.

Damage was equally heavy in the districts of Shikaghi and particularly of Jum and in the settlements along

the Aafrine river, where it is said that the flow of water

in streams was reversed for some time before they dried

up, while elsewhere the flow of stream water temporarily increased. The ground opened up for some distance

as a result of the earthquake; the Orontes river overflowed its banks, destroying bridges and embankments so

that cultivated land was flooded, and the river altered its

course permanently. The exact location of these changes

is not known, but may have been where the routes from

Antakya and Lattakiya to Aleppo cross the Orontes, that

is between Hadid and Jisr as-Shugr, rather than further

north. The small town of Kilis was destroyed with loss

of life – it is said that there existed an inscription on

the Cekmeceli Cami in the town that commemorated the

event.

Harim and Armenhaz, further to the south, were

totally destroyed, and Darkush was ruined partly by the

shock and partly by landslides that carried away part of

the village. Near there, at an unknown locality, a landslide temporarily blocked the Orontes river in the valley

to the north towards Hadid. South of Darkush narrow

gorges of the Orontes collapsed and the village of Jisr asShugr was entirely destroyed, with loss of life. Individual

farmhouses and small settlements in the area of Jur were

razed to the ground.

Han Sheikhun, al-Riha, Idlib and particularly

Maarat were almost completely ruined, but the loss of life

was not great. Houses collapsed in these places but large

buildings, although shattered, were left standing, except

in Maarat, where they were brought down by aftershocks

that also crevassed the banks of the Orontes. It is said that

damage extended to Hama and that the town suffered as

much as did Aleppo.

Aleppo, a city built almost entirely of stone, with

about 40 000 houses containing a population of about

200 000, including the suburbs, was ruined. Statistics

for earthquake casualties are generally reckoned to be

grossly exaggerated; however, the best estimate of casualties in Aleppo is that made some time after the event

by European consuls, who reckon that 7000 people were

killed within the walls of the city (the gates of which were

shut for the night at the time of the earthquake) and

about 200 in the extramural part of Aleppo, where most

people were able to escape into the gardens.

The shock, and its many destructive aftershocks

during the ensuing 10 minutes, killed 5300 Arabs and

Turks, including Sheikh Abdallah ar-Razah, a religious

leader of Aleppo. The Jews suffered most, since their

quarters were badly built and with very narrow lanes

between the houses; out of a total of about 3000, 600 were

killed, mainly women and children. The Armenian community lost about 1400 and the very much smaller European community lost 13, including the Grand Dragoman

and the Austrian consul, who was killed in the street in an

aftershock occurring a few minutes after the main shock.

Indeed, most of those killed within the walls of the city

perished in the narrow lanes trying to escape during this

aftershock period. The walls of the citadel were ruined

but the 18-m-high watchtower and the nearby 86-mdeep draw-well were not affected. Many hans and souks,

including that of the perfume-makers, were ruined. The

al-Fanig gate collapsed and the Hanaqa al-qadim was

damaged. The houses of all the Europeans, both public

agents and private individuals, were entirely destroyed,

as were all Christian convents and other buildings. The

large building that had been the British consulate for 230

years was ruined, although not entirely reduced to rubble. In general, the upper part of the city of Aleppo and

the European sector suffered less than the rest, but damage was so widespread that most European merchants

removed themselves to Cyprus after the earthquake.

It is said that before the earthquake the temperature of well water had perceptibly increased and that after

the earthquake the flow of the Quwayq river was arrested

for many hours near Hailan, where there was much

damage.

The town of Antakya and its surrounding villages

were ruined. The town was evacuated and its inhabitants

camped in the open fields for a long time. Many small settlements in the upper and lower Quseir area were razed

to the ground. The shock did not cause any extensive

ground ruptures near Antakya, although crevasses were

to be seen in the low ground near the town and in the

Amik valley. Water issued from many of these, but soon

subsided, this being a clear indication of the liquefaction

of the ground.

Beilan was heavily damaged, presumably without

casualties, but some of its more substantial buildings were

almost totally destroyed. At Iskenderun the shock was

strong enough to destroy a number of houses and to cause

extensive liquefaction along the coast and in the plain at

the foot of the Gavur mountain, where areas of cultivated

land turned into marshes, the ground water rising permanently to well above ground level and inundating a number of settlements. At Payas damage was more serious –

some houses near the old port sank into the ground but

most of the people escaped unhurt.

Damage along the Syrian coast was also serious.

One third of Lattakiya was again destroyed and a further third was damaged. Not a single warehouse in the

harbour area was considered to have escaped; the convent and the French consulate were damaged and 48

people were killed and 20 injured. The town was completely evacuated. In the marina, about 15 km from the

town, the ruined fort, the mosque and the large han

which had been rebuilt after the 1796 earthquake collapsed and houses and stores were considerably damaged. Jeble was more heavily damaged and people were

killed. The great mosque that housed the tomb of Sufi

Ibrahim b. Adham collapsed. Damage was also reported

from Markab, where, among other buildings, the castle of

the Crusaders on the mountain partly collapsed.

Damage extended to the region of Adana and

Misis, where villages along the road to Antakya were

ruined. It is not known whether this was due to the severe

shaking or to the widespread liquefaction of the ground

which was reported from the low-lying plain of the Ceyhan river. Kozan, Maras and Nizip also seem to have been

affected, although contemporary reports seem to exaggerate the effects of the 1822 earthquake, which they confound with the effects of that of 1811, a much smaller

event that caused considerable damage to these towns.

Further away, the shock was strongly felt in Tarsus. At Homs it caused unspecified damage while in

Tripoli and its dependencies it was violent and caused

damage in places.

The earthquake was reported from Beirut and

Sidon, and from Damascus, where people spent the night

camping in the open spaces and outside the city, which

is said to have suffered slightly. In Jerusalem and Gaza

to the south, and in Trabzon, Tokat and Merzifon to the

north, the shock was strongly felt; it was not, however,

reported in Alexandria, contrary to later statements that

confuse this place with Alexandretta (Iskenderun). The

earthquake was felt throughout the island of Cyprus, particularly at Kition and Larnaca, where it caused some

concern, but it was not so strong at Limassol. Northeast of

Aleppo, at Urfa and along the Euphrates, there is some

evidence that both the main shock and the aftershocks of

August 15 1822 and June 30 1823 were felt and caused

some damage. Contemporary reports also suggest damage at Kiyarbakir and add that the earthquake was perceptible throughout Mespotamia (Jazira).

The main shock was felt by ships sailing between

Cyprus and Lattakiya and halfway between Alexandria

and Cyprus. There is no evidence that this event was associated with a seismic sea wave in the eastern Mediterranean or with an abnormal fluctuation of sea level.

Destructive aftershocks occurred on 15 and 23

August, 5 and 29 September, 18 October 1822 and June

30 1823, the sequence terminating in March 1824.

It is not possible to determine the total number of people killed in this earthquake. Contemporary

estimates vary between 30 000 and 60 000, while more

sober estimates put the total at 20 000 dead and as many

injured. Internal evidence does suggest, however, that the

destruction and loss of life may have been very great.

For example, although the number of people killed in

the Aintab (Gaziantep) region is not known, the fact that

the authorities issued instructions after the earthquake to

regulate the handling of inheritance cases that arose in

the district is itself an indication of the gravity of the situation. A further indication is that Aintab (Gaziantep),

Aleppo and other affected districts were relieved of the

obligation to provide supplies for the Ottoman troops in

the area, the plea for assistance from the Ottoman Porte

being met with the rejoinder that there was no other solution than enduring God’s decree. It is said that the loss

of life amongst the Armenian population in Aintab, one

third of the total, was so great that there were no priests

left to officiate at burials and that the amount of property

left by those killed without surviving relatives to inherit,

which passed to the state, was very great. At Kilis it is said

that the loss of life was so great that there were too few

people to pick the olive harvest that year.

The serious damage caused to the city of Aleppo

had social implications. Many left and settled elsewhere,

while business life was so much affected that the French

consul requested permission from Paris to move his office

to Beirut; he was only one of the Europeans who never

returned to Aleppo after the earthquake. Some built

timber-frame houses outside the walls on a site that eventually became the al-Kattab suburb, where permission

was given for a church to be built. The extent of damage

to the part of the city outside the walls is reflected in the

fact that the moat was soon filled with the rubble from

the houses thrown down in the earthquake. One of the

reasons for the decline of Aleppo as a commercial centre in the early 1800s was the earthquake of 1822 and its

long and damaging aftershock sequence. For many years

after the earthquake only a few huts were to be seen on

the ruins of the villages further south, along the Orontes

river at Darkush and Jisr as-Shugr.

Much of the news about the earthquake originated shortly after the event from the consular correspondence and letters from missionaries published in the

European press. Communications with the stricken area

were made difficult not only by the civil war raging at the

time but also by the restrictions imposed on movements

as a result of the cholera epidemic that spread into the

region from Mesopotamia. To make matters even worse,

Bedouins descended on Aleppo and the eastern bank of

the Orontes from the Syrian desert and plundered the

ruins. Marauding tribesmen and renegade soldiers made

the countryside unsafe for a number of years after the

earthquake.

News of the disaster reached the Ottoman Porte

on August 28, but was kept from the public during the

festivities of the Feast of Sacrifice. Except for the temporary relief from taxation mentioned above, no evidence has yet been found that the affected areas received

any outside assistance. The Levant Company raised subscriptions in London for the sufferers, but only a small

part of this was spent since the Porte did not, on this

occasion, permit its subjects to be relieved by a foreign

nation.

The importance of the earthquake of 1822 lies not

only in the fact that it was one of the largest shocks in

the Eastern Mediterranean region, but also and mainly in

that it occurred in an area that has been totally quiescent

during this century.

What follows is a sample of the sources of information available for this event, which are too numerous

to incorporate as part of the text.

References

[1] AN Corr. Consul. (Beyrouth), (Alep), (Tarsus) and (Larnaca).

[2] BBA CD 6009.

[3] BBA MMD 8950.4, 26.

[4] PRO FO 78/110.35, 195/39, 112.418 (Constantinople);

78/110.40 (Aleppo); 78/112.31 (Alexandria); 78/112.10/

1 (Latakia, Aleppo) addendum; 78/112.82.6 (London);

SP.105/140.311–347, 142.203–208 (Antioch); 105/141.307

(Aleppo); and 105/141.291–301 (Suedia).

[5] PGG 1822, 10.9.

[6] PJD 1822, 10.2, 4, 11.25, 12.31.

[7] PMU 1822, 10.5, 11.13, 1823, 1.1.

[8] PTT 1823, 1.17–28, 3.2, 9.30.

[9] Anonymous (1822a).

[10] Anonymous (1822b).

[11] Anonymous (1822c).

[12] Anonymous (1822d).

[13] Anonymous (1823a).

[14] Anonymous (1823b, 2–7).

[15] Anonymous (1854).

[16] Aucher-Eloy (1842, 84).

[17] Barker (1823, 104–107; 1825, 64–65).

[18] Barker (1876, 321–341).

[19] Beadle (1842).

[20] Bodman (1963).

[21] Brun (1868, 38).

[22] Callien (c. 1830, 15–55).

[23] C¸ evdet (1891, xii. 45).

[24] Derche (1824).

[25] Dienner (1886).

[26] Ehrenberg (1827, 602).

[27] Elisseeff (1967, 766).

[28] Esad (f. 81r).

[29] Galles (1885, 3–7).

[30] Al-Ghazzi (iii. 329).

[31] Guzelbey and Yetkin (1970, 121). ¨

[32] Guys (1822, 301–305).

[33] Jowett (1825).

[34] Kadri (1932, 105).

[35] Le Calloc’h (1992).

[36] Lemmens (1898).

[37] Neal (1852, ii. 94).

[38] Nostitz (1873, i. 117).

[39] Oberhummer (1902).

[40] Prevelakis and Katsiadakis (2005, 345, 356).

[41] Regnault (1822).

[42] Robinson (1837a, 306; 1837b, ii. 253, 312).

[43] Sale (1840).

[44] Sauvaget (1941, 203–219).

[45] Schmidt (1867a, 37).

[46] Al-Tabbakh (Halab, iii. 400).

[47] Tarih-i Esad 2083. f. 81r.

[48] Verneur (1822, 6, 154, 394).

[49] Wolff (1860, 272, 294)

References

Ambraseys, N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of

seismicity up to 1900. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Table 2

Table 2 Table 1

Table 1 Table 4

Table 4 Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 3

Figure 3 Table 1

Table 1 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 5

Figure 5